interviews

Inside the Process of Translating Korean Literature

Anton Hur, Sandy Joosun Lee, and Sung Ryu on their path as literary translators, creative process, and book recommendations

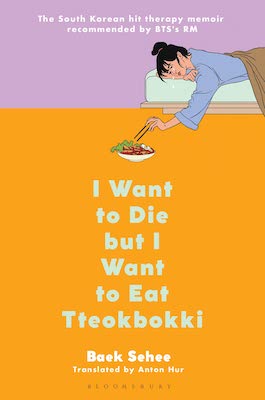

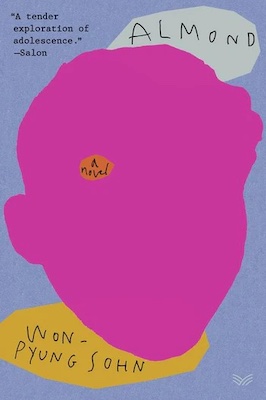

Translated Korean literature in the English-speaking world has seen a remarkable growth in the past couple of years, the rise of which has been propelled by the Smoking Tigers, a small but mighty cohort of nine literary translators working from Korean to English. Collectively, they have translated a diverse range of books: a mind-boggling sci-fi story collection, a critically-acclaimed, queer, coming-of-age novel, an ever so timely memoir about mental health, and a tender YA novel lauded by BTS’s RM himself. While they are not the first or the only translators bringing Korean stories to an English-reading audience, the Smoking Tigers have been critical in recent years in championing contemporary and emerging Korean voices that provide a peek into Korean life and push our understanding of literature beyond Western conventions.

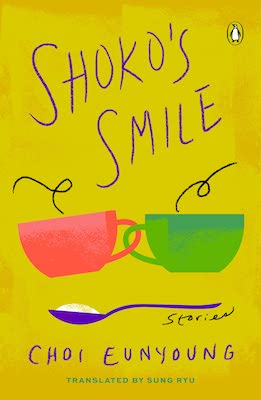

The translators featured in this article are three Smoking Tigers members who have seen tremendous success internationally. Anton Hur was longlisted not once but twice for the 2022 International Booker Prize for his translations of Bora Chung’s Cursed Bunny and Sang Young Park’s Love in the Big City. Sandy Joosun Lee’s translation of Won-pyung Sohn’s Almond made best-of lists at publications like Entertainment Weekly and Salon. On top of receiving stellar reviews for her translation of Choi Eunyoung’s Shoko’s Smile, Sung Ryu also had three books of translations published within a single year in 2021.

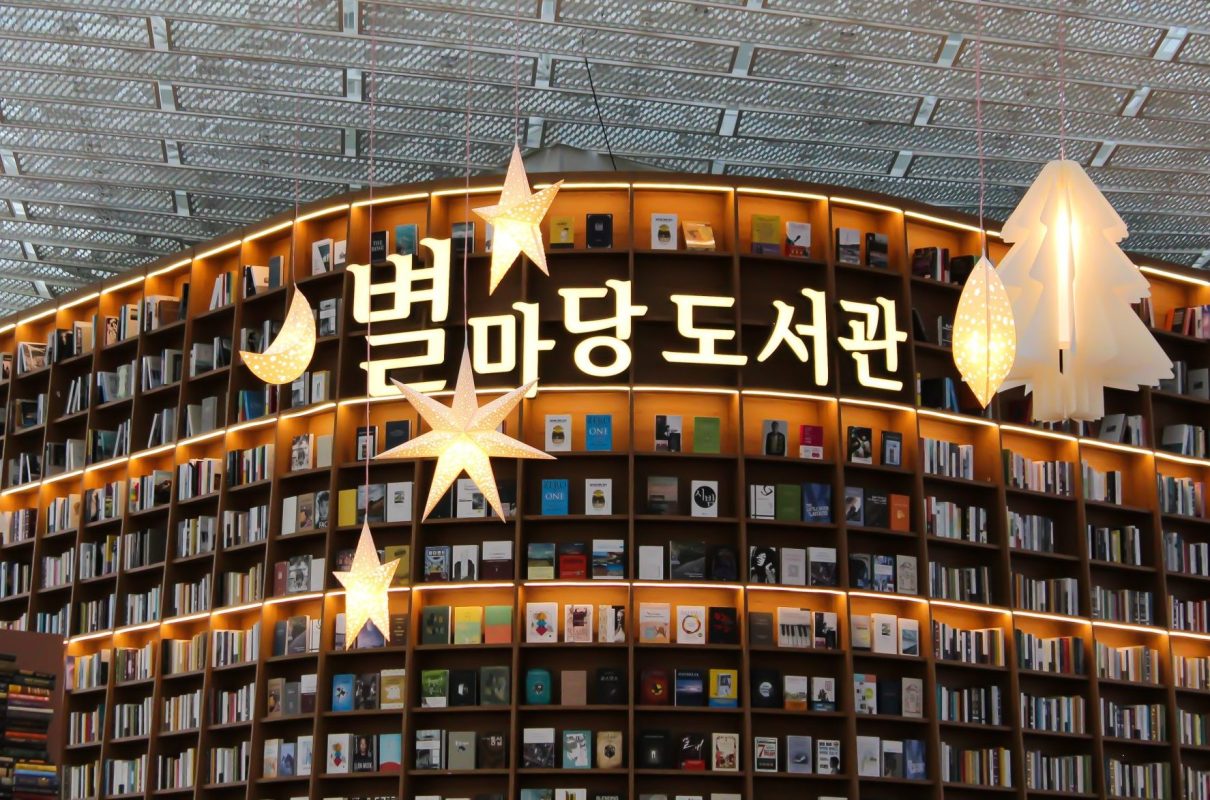

To commemorate Korea’s Hangul Day a.k.a. Korean Alphabet Day on October 9, I video called with Hur, Lee, and Ryu to discuss their careers as literary translators, the art of translating the Korean language, and the current landscape of Korean literature.

Anton Hur: I’m one of the few full-time Korean to English literary translators in the world. I’m not diaspora myself and I have full Korean citizenship, but I had to interpret for my parents who were not living in Korea. We moved a lot so half of my schooling was overseas, hence a perfect bilingual education. When you’re bilingual in Korea, you get all these opportunities to make a little pocket money through translating and interpreting. After college, I started to build up my client list and take the profession seriously. After ten years of freelance translating and interpreting, I eventually got the chance to audition to become Kyung-sook Shin’s new translator and I got the part. I proposed The Court Dancer to her agent and that became my first book. For a while, I also had a job in tech and was translating two books on the weekends. But I left the company when I won a PEN grant to work on a third book and realized I couldn’t translate three books on the weekends. I’ve been thinking in terms of runway for six years now in terms of when I might have to go find another job. My current runway extends to next June.

Brandon J. Choi: I recently finished your translation of Baek Sehee’s I Want to Die But I Want to Eat Tteokbokki. Since you have translated across multiple genres and forms, was translating this memoir different in any way?

AH: I don’t think so. People always ask me how I choose the books I work on. The most important thing is the language. They have to be good writers. Translating good writing is easy. I have never talked to Baek Sehee but while I’m sure it was a very harrowing book to write, it was a very smooth book to translate because she is an excellent writer. Her honesty just vibrates off the page. I thought that as long as I could convey her feelings and insights as accurately as possible, then people would get the book.

BJC: I didn’t realize you had never met her. Do translators often work closely with their authors?

AH: For me, the norm is to not really know my authors. I get such a visceral feeling when I read their books. I understand what they’re saying and I don’t need the author to explain anything to me. A part of me doesn’t want to bother the author because if I were being asked questions about my work after I finished it, I would think, why is this not clear to you? For example, Kyung-sook Shin is a god of Korean literature. She doesn’t need to explain herself. Everything is clear to me because I’ve been reading her for forever. There are writers I am close to like Bora. We talk all the time but we never talk about work. We’re usually exchanging memes on our email thread. I did drag Bora out to a lot of press events though. We called it the Bora World Tour.

BJC: I want to go back to what you said about good writing. What does good writing mean to you?

AH: There’s a big oral element for me. I have to hear it. Kyung-sook Shin, for example, in Korean, does not use fancy words or complicated sentence structures. In Violets, there is a moment where the third person omniscient becomes the first person omniscient and it’s really noticeable because I hadn’t seen that in any of her other literature. Her prose in Korean has a rhythm to it that rocks you into your deep emotions. It’s very difficult to decode but it’s very clear that she is writing to me in absolute silence. I think it’s something ineffable and primordial like that.

BJC: You’re also a writer yourself. Has that changed your perception of “good writing”?

AH: I translated Lee Seong-bok’s Indeterminate Inflorescence, a collection of aphorisms broken down from his lectures, and that book was life changing for me. He talks about how you think you’re writing with your brain but you’re not. Your hands or your pen are doing the writing so you have to let your pen write and not think about it. Each word has another word coming out after and you can sense the shape of that word. You have to write down the sounds no matter how absurd they are. Eventually, the words keep coming out and you have a book. I tried it out and it worked. I wrote a book and it’s now being shopped around by my agent.

BJC: That’s incredibly poetic. I love that.

There’s a lot of racism in the industry because they expect an English translator to be white and preferably a man.

AH: For me, writing is really about the sensitivity to yourself. If you are sensitive, you can hear the words that are trying to come out of your subconscious. I always knew my subconscious was how I translated because I can’t explain how I came to translate one sentence into another. It surfaces from the depths. The machine is down there and it’s like a black box that I can’t figure out.

BJC: Since your 2022 Booker nominations for Bora Chung’s Cursed Bunny and Sang Young Park’s Love in the Big City, have you noticed any changes in the Korean literary scene?

AH: I think there’s more respect for genre literature after Cursed Bunny. Sang Young Park has always been award winning so I’m not sure how much the nomination affected him. But I will tell anyone reading this that he loves getting messages from around the world from readers, especially queer readers, who are moved by Love in the Big City.

BJC: What has changed for you?

AH: So why I agree to interviews, especially in Korea, is because I’m so tired of going to rights holders and them not giving me the rights to a book. There’s a lot of racism in the industry because they expect an English translator to be white and preferably a man. If you look at some of my bios, I always mention that I was born in Sweden first. I’m trying to play on people’s racism. I guess it’s bad because it perpetuates it to some degree but you have to understand, especially in the beginning of my career, it was very difficult to have people take me seriously. This has gotten a bit better now that I can say that I’m a Booker nominee.

BJC: That’s infuriating. I actually appreciate reading Korean books translated by Korean artists.

AH: I’m very grateful for Korean American readers because they’ve been hugely instrumental and supportive. Korean American writers like Alexander Chee and R.O. Kwon are so selfless. So many Asian Americans have come to bat for Korean literature in translation.

Basically, we’re a website and a bunch of friends who occasionally workshop together. People think we’re like the Avengers of Korean translation but it’s not as huge of a deal as they make it.

BJC: Along those lines of community, can you tell me about the Smoking Tigers?

AH: The Smoking Tigers became a thing at the British Centre for Literary Translation in 2017. The Starling Bureau, which is another translator collective, came and gave a talk. We thought we were also like a team so why not make it formal? Because I’m a web developer, I put together the site. Basically, we’re a website and a bunch of friends who occasionally workshop together. People think we’re like the Avengers of Korean translation but it’s not as huge of a deal as they make it. I don’t want people to think of it as a gated community because it really isn’t.

BJC: If someone is just starting out reading translated Korean literature, what would you recommend?

AH: The Girl Who Wrote Loneliness by Kyung-sook Shin, translated by Ha-yun Jung. That book is the most important work of postwar literature in Korea. It also tells you how to write. It’s a very important book on every level.

BJC: Who is a translator you admire and would like to shout out?

AH: So many. I’ll say Mui Poopoksakul, who is a Thai translator. There was no full length Thai translation published in the U.K. or the U.S. until she came along and basically became Thai literature in translation. My husband, who is Thai American, and I are huge fans and are very grateful to her. I admire her because she operates like a literary translator in the year of 2022. It’s not just translating. We have to be responsible for the discourse that surrounds that translation. She does all of that without something like the Smoking Tigers to have her back.

BJC: The American versions of I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki and Cursed Bunny come out in November and December respectively. Did I miss anything?

AH: Kyung-sook Shin’s I Went to See My Father comes out next April. Djuna’s Counterweight is coming out in July. Lee Seong-bok’s Indeterminate Inflorescence is coming out in September.

Sandy Joosun Lee: Being a translator is actually my only job. I started my career as an in-house corporate translator and interpreter. It was for a startup animation studio called Studio Mir in Korea that produced some of the hit animated series in the States. I got to translate a lot of fun, exciting animation scripts and interpret for artists and directors. I still work at that studio and this year will mark my 10th anniversary. I find it extremely lucky to work in an environment that gives me a sense of mutual growth. The company took a chance on me and I guess I took a chance on the company.

Brandon J. Choi: How did you end up working on Almond?

SJL: A few years into my job, I started having this thirst to hone my skills as a translator and writer. The studio was much smaller back then so I had no translating mentors to look up to or colleagues to share this thirst with. I started taking translation courses at LTI Korea. I was in a workshop course where I had to choose works that I would translate. Almond happened to be my very first work that I chose and it started as an assignment at LTI. I got a lot of painfully helpful feedback from the professor, Sora Kim-Russell, who is also an esteemed literary translator, and my colleagues in the course.

BJC: What drew you to the book?

SJL: I picked up this book and it was love at first sight. It was the story that drew me in first. Looking back, I realize I was drawn to the character because he reminded me of my brother, who has autism. The connection was obvious to everyone who knows me, but interestingly, it hadn’t dawned on me until recently. I realized that translating Almond was a personal and therapeutic process for me and allowed me to tap into my brother’s world. It gave me such comfort as someone who has a family member with a neurological condition.

BJC: Can you talk about how closely you worked with the author?

SJL: The author pretty much let me translate the whole thing until the last draft. We didn’t meet up and only communicated virtually. She was very thorough and gave feedback line by line and even suggested better translations. Her feedback was very helpful in honing the tone of Almond but, for the most part, she left me to finish the translated version.

BJC: The tone and prose is so distinct. While reading it, I was trying to translate some lines myself to the original Korean. In the translator’s note, you discussed your experience translating Yunjae and Gon, the two central characters. Can you elaborate on that? What was it like inhabiting the voices of such young characters?

I realized that translating Almond was a personal and therapeutic process for me and allowed me to tap into my [autistic] brother’s world.

SJL: I have a thing for YA novels. I just gravitate towards them. I think I have a young, nervous tone that I find to be compatible with those books. The tone and prose of Almond was definitely what drew me to it. I found compatibility partially due to my experience with my brother’s condition. I experienced for myself that what is left unsaid can be powerful so it was natural for me to pick up the tone of the Yunjae.

BJC: Both characters change so much throughout the novel. I think that type of development is also the beauty of the YA novel. Were there specific parts of the characters that you found frustrating?

SJL: Gon was a hard one. I don’t cuss that much and I’m not a very emotional person myself so it was very difficult for me. I actually got a lot of feedback from a friend who is an expert in swear words, which was helpful. He helped me find the right cuss words for each and every moment of Gon. I was also very mindful of Yunjae’s outbursts that I didn’t want to drop. It’s something I got a lot of feedback on while communicating with the author.

BJC: Since you translate for your day job too, are there particular aspects of the Korean language that you find unique and especially expressive? Or any specific difficulties you have had while translating Korean?

SJL: This is a hard question. If I had to choose one thing that I find unique about the Korean language as opposed to the English language is that I can drop the subject of a sentence and it still works grammatically. The pronouns can be omitted and therefore the sentence can be gender free. I find this particularly fascinating and very timely. I remember when I translated Almond and some of the sentences had no specific gender pronouns associated with the subjects. I was unknowingly stereotyping certain types of professions to be either feminine or masculine and used incorrect pronouns. When the author came back to me after reading my draft and corrected the pronouns, I was embarrassed of my stupidity and unprofessionalism. I guess that’s the beauty and frustration for me.

I want to borrow what Morgan Giles, the translator of Tokyo Ueno Station, said in an interview once. She said that nothing is untranslatable. It’s just that we haven’t been imaginative enough. So if there is any frustration I run into, I tell myself to be more imaginative to pull it all together.

BJC: What are you working on now?

I was annoyingly stereotyping certain types of professions to be either feminine or masculine and used incorrect pronouns.

SJL: I just finished translating the manuscript for a YA novel called Dallergut Dream Department Store by Lee Mi-ye. It’s a fantasy story about a magical store where you can buy all kinds of dreams while you sleep. It’s such a fun and heartwarming story for both kids and adults. I’m hoping that will be my next publication. I also started going back to write my own story but it’s still in progress. I have a very unique family and background that I want to delve deep into. Of course, my brother will be involved and hopefully I can finish it before I turn 70.

BJC: Can you tell me about your experiences as a member of the Smoking Tigers?

SJL: I cannot talk about Almond without talking about the Smoking Tigers. We are a collective of active, successful Korean to English translators. They are valuable readers who helped me shape the tone of Almond and some of them have become my closest friends. I am proud to say that they are the source of inspiration and pride. I couldn’t be happier to grow with them and to celebrate their achievements as my own.

BJC: If someone is just starting out reading translated Korean literature, what would you recommend?

SJL: I would obviously say to start with Almond. Not because BTS read it but because it’s an easy read to start with. It will also leave you with some poignant reflection on complex ideas like emotion or lack thereof as well as trauma and life.

BJC: Lastly, who is a translator you admire and would like to shout out?

SJL: I will start with my first literary translation teacher, Sora Kim-Russell. Her work Our Happy Time by Gong Ji-young was the first ever Korean translated book that inspired me to get into this industry and got me to where I am. And of course, Anton Hur, who was double listed for the Booker this year, as well as Sung Ryu, who encouraged me to push forward and made Almond possible.

Sung Ryu: I translate mostly from Korean to English but also from English to Korean. My first literary translation class was in 2013 at LTI Korea and I loved it enough to quit my full-time job to study translation in earnest. I studied translation for a total of seven years but it was only in 2021 that my first book translation came out. But it’s funny how life catches you off guard because, after years of waiting, I had three books come out in the same year. But then in another twist, shortly after I started translating the first book, I fell ill to the point that I consider it a personal miracle that I finished all three translations on time. So since I handed in Shoko’s Smile in March 2020, I’ve been hibernating and healing but am regaining the desire to translate again.

Brandon J. Choi: I’m ready for three more books. Shoko’s Smile was one of my favorite reads last year. What was it like translating a story collection with numerous characters and styles?

SR: Interestingly enough, translating Shoko’s Smile felt like translating a novel because the characters share a similar voice. All of the narrators are women and they meet and ultimately lose someone very special in their lives, so their sense of grief is what knits the stories together.

BJC: Was there a particular story you were drawn to most or found challenging?

SR: The moment I start translating a story, it becomes my favorite story. I had a bit of difficulty translating “Michaela.” There are three women characters and they’ve been indirectly affected by the Sewol ferry disaster. Only one of the characters is named and the rest are unnamed. Even for Michaela, she is only directly referenced by her pronouns. In rendering that into English, I had to somehow make it clear which of the women “she” was referring to. Korean doesn’t have this problem because it doesn’t require personal pronouns. In the end, the ubiquity of “she” in my translation worked out well because it highlighted the anonymity and universality of these characters and the fact that Sewol could’ve happened to any of us.

BJC: You also translated Kim Bo-Young’s I’m Waiting for You with Sophie Bowman. What were the differences and challenges in translating sci-fi?

SR: When translating sci-fi, having the story worldview down pat is as critical as nailing the voice. In the set of stories that I translated in that quartet, the universe was mind boggling. I had to ask Bo-Young many rounds of questions and even included diagrams to make sure I understood what the world looked like. It made sense for me to spend as much time as I could to understand and reassemble the world that Bo-Young had researched extensively to build.

BJC: How was co-translating the book with another translator?

When translating sci-fi, having the story worldview down pat is as critical as nailing the voice.

SR: There are many models of co-translation. We translated two stories each independently then swapped manuscripts to edit each other. We were very familiar with each other’s source texts so we didn’t just edit for readability, but also compared and discussed our readings. Readings are bound to differ so when we couldn’t figure something out, we went back to Bo-Young. But by the time I got edits on my translation from the publisher, I had gotten too sick to review them myself so Sophie stepped in. By the time Sophie got edits on her translation from the publisher, she also had a lot going on in her life so I negotiated the edits on her behalf. Although we translated independently, I would say we were intimately dependent on each other. I’m convinced that if either one of us had translated the entire book alone, it would not have turned out as beautifully as it did. The key to a successful co-translation is balance—balance of workload, balance of skill, and above all, mutual trust. I feel really lucky to have worked with Sophie.

BJC: You also translate from English to Korean. How does this process differ for you?

SR: Korean to English is easier for me but as I grow more comfortable writing in Korean, my English to Korean is catching up. I have found that Korean has really flexible syntax. You can drop things like the subject, object, plural markers, or personal pronouns and the sentence would still be able to stand on its own. So when I read Korean, there’s a lot of reading between the lines. Rendering that into English means I often have to decide which of those blanks to fill in. When working into Korean, I have to think about what excesses to trim away from the English syntax to create some breathing room. It would sound so awkward if I carried over every single piece of information from the English into Korean.

BJC: Out of curiosity, how do you handle translating idioms?

SR: It depends. My immediate urge would be to try to at least carry over this idiom because it contains a worldview of the source text and the source culture. But if it gets in the way of the voice of characters or the emotions of a scene, then I wouldn’t try to literally translate the idiom.

BJC: I love your webtoons on Korean Literature Now. I found them so tender and I wanted to ask: what have been your favorite and most joyous moments as a translator?

SR: I love this question because when translators get together, we tend to complain a lot about how demoralizing this job and industry are. But there have been moments of joy in every step of the way. Even right from the start: that adrenaline rush when a book commands me to translate it. The inspiration after a particularly thought-provoking workshop. My peak fangirl bliss when I get to meet my author for the first time. The sublime catharsis when I find the perfect pitch and flow of my translation. The relief of finally finding a home for my work and being able to tell my author that after years of making them wait. I remember ugly crying when Honford Star told me that they wanted to publish Tower by Bae Myung-hoon. It was my first sale, which came seven years after I started dabbling in literary translation. It’s a moment that I don’t think I’ll ever forget.

BJC: What’s coming up for you next?

The key to a successful co-translation is balance—balance of workload, balance of skill, and above all, mutual trust.

SR: I’m working on rebuilding my body from scratch so that I can translate more sustainably. I do have a translation that’s just been sort of gathering dust that I haven’t actively pitched yet. It’s a translation of the Jeju myth of Jacheongbi. She’s a girl who outwits and outlasts all her patriarchal abusers. She goes on to win the hand of her lover and a seat among the most celebrated goddesses on Jeju Island. For me, it’s a fascinating tale of female aggression and desire. That whole island is a treasure trove of myths.

BJC: Thank you for being honest about your health. One big thing that I’ve learned from my mentor this year is how to be gentle with and kind to myself as a writer.

SR: Thank you. I debated how much I should share about my hiatus and health. In the end, I couldn’t omit that part of my career journey. It might reach some other translators who might also be struggling. I want to let them know that there is someone out here who is biding her time and trying to see this as a long run. I love translation too much to quit it but I need to figure out how to make it a healthier practice.

BJC: If someone is just starting out reading translated Korean literature, what would you recommend?

SR: Almond by Sohn Won-pyung. Sandy Joosun Lee’s powerful translation is one of the most highly rated and widely read Korean literature in English translation. I will also recommend Soje’s translation of Lee Hyemi’s Unexpected Vanilla and Emily Yae Won’s translation of Hwang Jungeun’s I’ll Go On. They’re both astonishing translations.

BJC: Who is a translator you admire and would like to shout out?

SR: I’ll shout out two translator communities that I am grateful for. chogwa is a zine that publishes multiple translations of the same Korean poem. It was started by Soje and brings people together to the pleasures of translating poetry. The other one is the BIPOC Literary Translators Caucus. It is a thriving community that has empowered me by simply existing.