interviews

Jean-Marc Rochette & Olivier Bocquet Discuss The New Volume in Their Internationally Acclaimed…

J

“Across the white immensity of an eternal winter, from one end of the frozen planet to the other, there travels a train that never stops. This is the Snowpiercer, one thousand and one carriages long.”

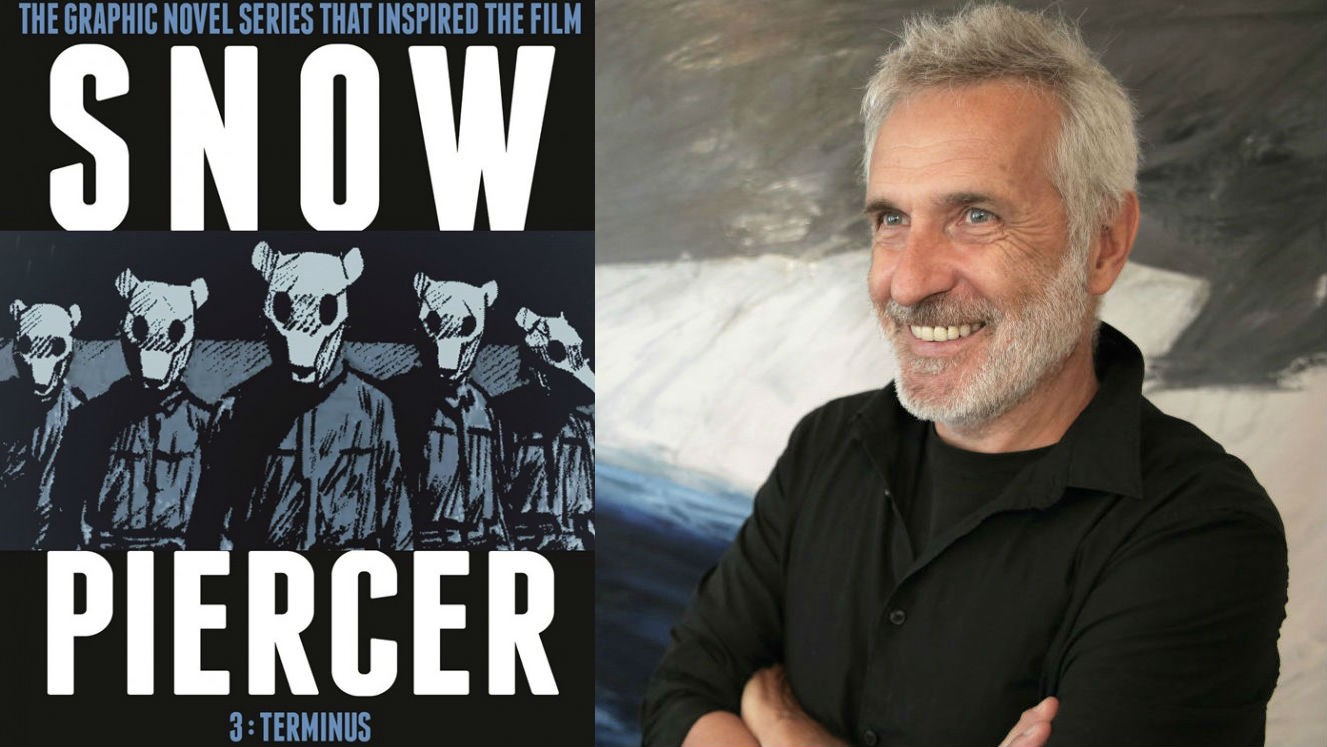

These are the first chilling words of the cult comic book Snowpiercer, written in 1982 by Jacques Lob and illustrated by artist Jean-Marc Rochette. Largely unknown at the time, Snowpiercer is now an international success. Unfortunately, Jacques Lob would not get to see his creation find the worldwide audience it has today due to his passing in 1990. But the train never stops, and Lob’s imagination traveled on. In addition to a film adaptation, his vision would inspire a further two sequels beginning with Snowpiercer 2: The Explorers, written by Benjamin Legrand, and continuing with the current book Snowpiercer 3: Terminus, written by Oliver Bocquet; both illustrated by co-creator Jean-Marc Rochette.

In Snowpiercer 3: Terminus mankind continues its struggle for survival inside the confined environment of the train until a strange musical signal leads the passengers literally off-track and into the unknown. For the first time in the series, humanity escapes its closed quarters, but enters what could be a fate worse than the train itself.

I had the pleasure of speaking with both Bocquet and Rochette on the collaborative relationship specific to comic book storytelling, the cost of immortality, and finding optimism amidst heartbreak. For readers who do not want plot points revealed I have flagged my final questions with a (SPOILER ALERT). Volumes 1 & 2 of Snowpiercer are available through Titan Comics; the third volume came out in stores last week.

Matthew Laiosa: A French comic book gets turned into a Korean movie with an almost all English-speaking cast. How has Snowpiercer managed to breach its own borders and what is it about the story that unifies these cultures together?

Jean-Marc Rochette: I think it’s the simplicity of Jacques Lob’s story that makes it universal. It can be pitched in a few words, and these few words sum up the whole story of mankind. The last survivors on earth are locked in a train that goes on forever, and society goes on too, as it has always done, through violence, inequality, and lies.

Olivier Bocquet: I think it’s a universal story because it’s like Noah’s Ark. It’s a story that’s told in almost every human culture. A big flood, people surviving, and a boat. This is not a flood, but it’s almost like one, and it’s not a boat, but it’s a train. It captures your imagination instantly. There are very few stories that are that strong and that simple. Jacques Lob did a great job because I think in a hundred years from now somebody else will do another Snowpiercer. It’s a story that will last because it’s not just about different cultures; it’s about different eras of mankind.

ML: In our cinematic world filled with remakes, reboots, and sequels there is a strange cultural demand for nostalgia. Even though Terminus is itself a sequel, you act against every expectation and immediately move the story outside of the train. Instead of repeating the past, you push the story forward. Was this something you set out to do?

JMR: The desire to make the sequel came step-by-step, and more specifically image-by-image. And the first image that came to me was an abseiling in a frozen elevator shaft. This vision made me think of a descent to hell. The image of the dog opening the gates of hell came to me pretty quick. It is of course Cerberus. And since I was describing hell, I tried to imagine a human and contemporary hell, which leads to visions of Chernobyl, of transhumanism, and everything that, to me, turns mankind away from the sane relation man should have with nature. At that point, I met Olivier and I think he immediately subscribed to that vision of hell. He brought with him his own fears, and his narrative talent, of course.

ML: Was it difficult to enter Jean-Marc Rochette’s pre-defined vision, or were your collective aims immediately synchronized?

OB: The story he wanted to tell was rough enough to put everything I wanted in, so it wasn’t hard to go into his universe because it wasn’t a closed one. He had visual ideas of scenes with themes that mattered to him, but I could do whatever I wanted in that. I think I would have had more difficulty if he wasn’t there. If someone came to me and said, we’re going to do another Snowpiercer with another artist and you will write the story, then we would have been forced to mimic what Jean-Marc and Jacques Lob already accomplished in 1982. But Jean-Marc is a man of his era. He grows with the world, and he doesn’t want to tell the story the same way he would have thirty years ago.

ML: Would you say that you challenged each other to do better work than one artist could do alone?

OB: When I first saw Jean-Marc, it was in the documentary film Transperceneige, From the Blank Page to the Black Screen by Jésus Castro on the blu-ray of Snowpiercer. He said he didn’t want to do comics anymore unless he finds a great script, and when he met me he said, ‘I don’t want to make just another comic book. I want to make the best one ever.’ And that’s quite a challenge, but I like it. Each time I came to see him with pages of script with something hard to visualize we wouldn’t say that can’t be done so let’s do something else. It was more like that can’t be done, but it is interesting so that is why we are going to do it.

ML: What were some of the scenes under discussion?

OB: The one that I remember most is when one of the characters is trapped in a prison drawer like you would find in a morgue. It’s fourteen pages of a man alone in the dark without moving and it had to be drawn. It was an important thing because it’s the moment when the character becomes a hero by going through an ordeal that a regular person would fail. We spent a whole day trying to figure out how to make that scene work so that the reader would feel the time passing, the suffering, the despair, the slow sinking into madness… with just a guy in a drawer. But when he eventually gets out of it, we wanted the reader to be in shock, just as the character is. When we finally nailed it, when we looked at Jean-Marc’s storyboard, we were both exhausted and happy. We had the feeling that we had done something that was beyond our expectations. Now, maybe it was just us two. We are not the readers, only the storytellers. We don’t know how readers will perceive that scene, or any scene in the book. But while making that book, we were always trying to go out of our comfort zone.

ML: In this episode of Snowpiercer we are introduced to the subterranean utopian theme park of Future Land. The best science fiction is often a reflection of our own society, so what aspects or our present were you most excited to include in this oddball future?

…in the end, if you live forever under the shadow of a nuclear plant, aren’t you already in hell?

JMR: To me there are two major themes in this book. The first one is life under the grip of atomic energy. I’m French, and France is the most nuclearized country in the world. I am also a native of the Rhône-Alpes region, which is the densest place on earth regarding the number of nuclear plants. This energy is the most perfect form of human alienation. We are dependent on and slaves of this dragon, this dangerous dragon that never dies and spits radioactive fire. In the town of Lyon, the biggest nuclear plant is called… Phoenix. I drew my inspiration from real photos of Chernobyl children to show the results of this radioactivity on our DNA: a production of nightmare monsters. The second theme is of course all the current attempts of genetic manipulations, the transhumanism that denies death. It denies death, but in the end, if you live forever under the shadow of a nuclear plant, aren’t you already in hell?

ML: For those not familiar with the concept of transhumanism, could you give a brief definition?

OB: It’s about enhancing humanity. You can be more than human. You can add microchips under the skin to do what you can with a smart phone, but you will do it with your brain. You could even replace your whole body and eventually stop dying. And that’s what transhumanism is all about. It’s the ultimate goal.

ML: If we our headed towards an earthly immortality what must we live without?

OB: You would probably have to stop making children. That’s a big sacrifice.

ML: And the logical progression of children being gone is the death of new ideas.

If people never die you never get fresh ideas.

OB: Yeah! I read an article a few days ago saying the death of great scientists makes science go faster because while the old ones are here, young ones can’t express themselves. If people never die you never get fresh ideas. You just work with the same old ideas. Plus, I think in a world without children we will lose our hope and joy. Kids are unconditional love. You ask every parent and they will say that they are willing to give their life for their kid. That has a real true meaning. If mankind doesn’t make kids anymore and you are just born to live forever, then what’s the meaning of your life?

ML: You’ll lose the idea of sacrificing yourself for anything. You’re only goal will be self-preservation.

OB: That’s very well put.

ML: Claustrophobia plays a large part in Snowpiercer. There is the obvious physical claustrophobia of the train, in addition to the passengers’ psychological claustrophobia regarding the unknown future. How does one best represent a character’s internal struggle in a visual medium?

JMR: The secret is the acting of the characters. That’s the most important. I consider my characters as real actors, so accordingly I ask them to play in the right key, kind of like on stage! Of course, the composition of the panels, the montage and the lighting are also very important, much like in a movie. And eventually, all this is intensified by the emotional power of the stroke, its energy, and that is very specific to the field of drawing.

ML: At one point in the story we discover a group of physically deformed painters. Do you think an artist, musician, writer, etc. must be ‘abnormal’ in some way in order to best express them self?

…maybe the deeper the wound is, the deeper the work is too.

JMR: Yes, I think you need to have something wounded. And maybe the deeper the wound is, the deeper the work is too. But I’m an incorrigible romantic…

ML: There seems to be a trend since the late 80’s for comic book characters to exist in the ‘real world.’ One thing I love about Snowpiercer is the theatrical and expressionistic tone in both the film and the book. It’s almost like a fairytale. Are you more drawn towards stories of realism or expressionism and why?

JMR: German expressionism was always a big influence for me, and strangely it just so happens that I now live in Berlin. I was influenced by Otto Dix, George Grosz, Max Beckmann and others; but also by Goya. I love the way they dramatize tragedy. Comics are a perfect medium for injecting dramatic caricature into a story. It suits me.

OB: I think a good story is like a symbol. In France, books and movies are more realistic, and there is no room for exaggeration. I think these stories are more efficient at saying what they want to say, but American movies have characters who are a little more over the top, and I think that is also a good way to tell stories. I clearly like it best. For example, in Little Miss Sunshine you step out of the cinema and you say that was a very cool movie about real human beings, but if you look at every character they are all crazy. Only put together are they like normal people.

ML: Something that continually boggles my mind is how something can become ‘mainstream’ decades after its inception. Marvel superheroes and Games of Thrones have never been bigger, and I know Snowpiercer is not on the same level, but it does seem more popular now than it ever was when it was first released. Why do you think that is?

JMR: Snowpiercer’s notoriety today cannot even be compared to what it was before Bong Joon-ho’s film. Because of him, it went from an almost forgotten French graphic novel to a cult book known in the entire world. To me, it’s a true miracle…

Geeks and nerds have won.

OB: Geeks and nerds have won. Anybody who was buying Star Wars toys and not opening the box in 1978 was a crazy person, but now they’re rich. And I don’t know how it happened, but I think it’s because of the Internet. I think all these people who were a little funny could all of a sudden express themselves and people realized they were serious, and there was a very large number of them. But it’s not all good because now Hollywood is making movies for them only. The new Star Wars is only fan service. They are getting what they want to see, which is the same movie again. To me it’s not interesting at all, but it makes tons of money, so on some level they must be right. But it’s a level I don’t care about.

ML: In the U.S. it is common for a comic book series to have the same author with many transitioning artists, but I am not familiar with a series with a single artist and three different writers. How have you maintained artistic control throughout the years?

JMR: Indeed it doesn’t happen a lot in France either. It all started with Jacques Lob’s death, and with my desire to relive the story. I had to look for new writers. I’m not a writer myself, but I know what I want to tell, just like a movie director. The hard part is to find the good writer, the one that will want to tell the same story as me. With Olivier, the partnership was perfect. I’m a former mountaineer, so I’ll use the metaphor of climbers roped together: there wasn’t any leader, but two companions completing each other, one better on the ice, the other better on the rock!

ML: You may have been the only artist on the series, but each book looks completely different. Volume 1: The Escape has an extremely precise aesthetic, Volume 2: The Explorers uses a more painterly technique, and Volume 3: Terminus has a sketch-like spontaneity. Was this due to your natural evolution as an artist or was there a specific intention behind each distinct look?

JMR: It was very subconscious. I’m a very free man and above all I didn’t have any external constraint, so I just did what I felt was right. I was confident that this freedom would not be prejudicial to the story. On the contrary it would add something libertarian, anarchist everywhere, including the form. It is, I think, the trademark of the story itself.

ML: In recent years your work appears to have been focused more in fine art painting. Was there any reason you took a break from comics, and what made you want to return?

I paint like people used to paint in my valley 30,000 years ago…

JMR: Painting is to me the most perfect form of image, like poetry is the most perfect form of narrative. Comics gave me the amazing privilege of being able to paint without having to sell my paintings. I paint like people used to paint in my valley 30,000 years ago — I live part time in Ardèche, near the Grotte de Chauvet, where you can see stunning prehistoric art. But I always come back to the comics, like an old couple that cannot live apart…

ML: I immediately associate European comics with the 46–62 page hard backed album format typical of Blueberry or Tintin. Comparatively Terminus is huge! Are more European comics adopting a longer format and for any particular reason?

I don’t think a story should be tied to a country…A good story is a good story.

OB: We read a lot of American and Japanese comics, and we are becoming used to seeing longer stories. Up until now people were ok with waiting one year to see the next episode of a 46-page story. Now we don’t want that. We want more to read, and we want it cheaper because each album is 10–20 euro, and we only have 46-pages to read once a year or once every two years, so that doesn’t really work anymore. Also, the artists and writers want to tell more interesting stories and we want the space to do them in. Currently graphic novels are selling well everywhere, even though traditional French comics do not. Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis which helped to start the craze for graphic novels, is French, so we should be doing more of that. I don’t think a story should be tied to a country. Everybody should be able to read anything from anywhere without knowing where it comes from. A good story is a good story.

ML: (SPOILER ALERT) One would not call Terminus a story of optimism, but by contrast this episode ends with the most potential for a future. Was there an intentional shift from pessimism to optimism?

JMR: The ending also came to me step-by-step. My first option was that only the leading couple would succeed in escaping this hellish place. They wanted to get out and be able to die in the cold, alone but free, facing the world’s beauty. Then, in the course of the discussions I had with Olivier, some hope arose, probably because of him. And in the end, only the hero dies, but with the most beautiful death: very old, voluntarily putting an end to his life by exposure, in the arms of his beloved wife that tells him a story full of flowers and spring. The flowers do eventually appear in the last panel, but one can wonder: when do they appear? At the moment of the hero’s death, or 100,000 years later? How optimistic are we, exactly?

OB: I’m an optimistic person, and I think killing everybody is an easy way out. I don’t subscribe to the idea that when a story is over and everyone is dead that it will give people so much to think about. I believe that’s lazy. I think the easy way to end the story is to blow up the nuclear plant, and I think almost everybody would have done that so that’s why I didn’t want to do it. I think it’s a fraud to tell people that a story has no hope in the end. Is that because you don’t have any more ideas? You don’t have better ideas? When I found the idea of the woman telling her dying husband what he wanted to hear, even if it’s not true, I thought it was heartbreaking. I thought it was beautiful. And I thought it was even more beautiful that it could eventually be true. She wasn’t really lying. She was hoping. She was giving hope to a dying man. And that hope is something I can’t take away from people at the end of a heartbreak like Terminus.