Interviews

Kamilah Aisha Moon, Salman Rushdie, and an Archive of Love

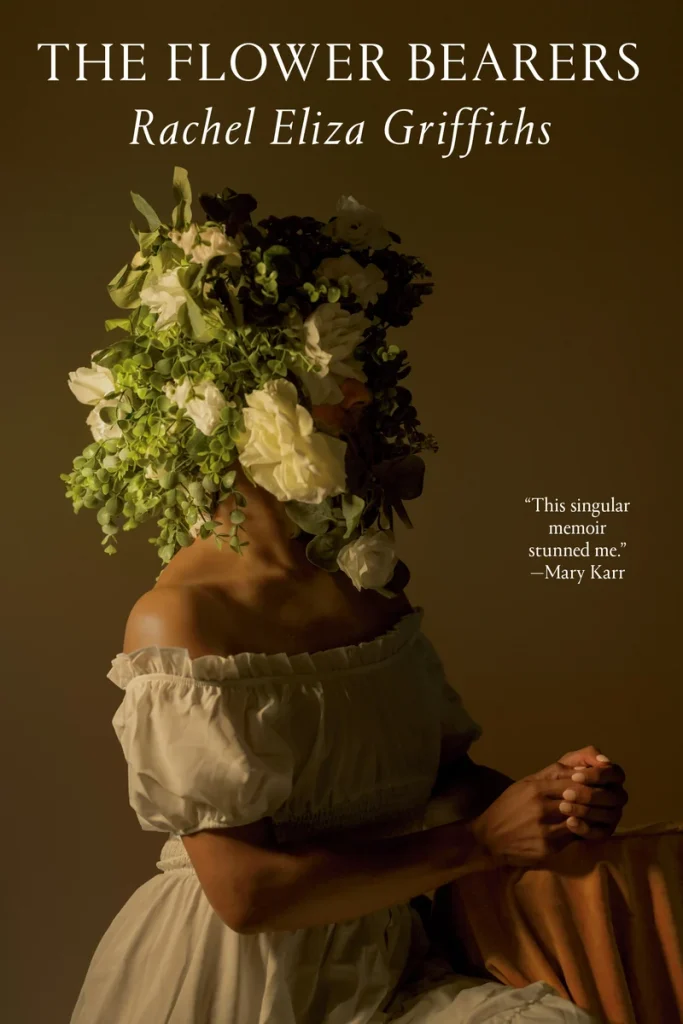

Rachel Eliza Griffiths on memorializing the most intimate griefs and joys in “The Flower Bearers”

Towards the end of The Flower Bearers, we see Rachel Eliza Griffiths visit the papers of Lucille Clifton and Alice Walker at Emory University and the papers of Toni Cade Bambara and Audre Lorde at Spelman College. We see her hands shake over Clifton’s spirit writing, carefully lift the first draft of Bambara’s The Salt Eaters out of a folder, and trace Lorde’s journals.

These visits aren’t research trips, and on this point, Griffiths does not want to be mistaken: “I’m not a scholar. I’m not an academic. I’m a madwoman.” Though the book holds a massive, exquisite and rigorous set of citations, the library trips are the completion of a journey she meant to take with her dear, deceased friend and chosen sister Kamilah Aisha Moon.

The Flower Bearers is born out of two close and tragic encounters in Griffiths’ life—the sudden death of Moon on her wedding day and the nearly-fatal attack on her husband, Salman Rushdie, which happened a few months later. It is a propulsive archive of love, loss, and reparation in lineage and sisterhood with those writers whom Griffiths and Moon aligned themselves.

The book landed on me like a sense memory. I met Griffiths and Moon twenty years ago at a writing conference where Griffiths and I discovered we lived on the exact same street in NYC. The friendship might have been born out of proximity but became a profound part of my twenties, for to know Griffiths and Moon, Rachel Eliza and Aisha, was to know and be part of a sisterhood in letters, to understand that even the smallest of small talk resides, as Griffiths puts it, “somewhere inside the complex language of Black womanhood.”

I knew the book would mean something special to me but I did not realize I’d read it in two days. Grief is a sneaky thing and this book helped me bear its beauty.

Over Zoom, Griffiths and I talked as madwomen do.

Nina Sharma: When I was preparing for this interview I suddenly felt inhibited, shy to share the joy of remembering Aisha through this book. Could you speak about how it feels to share this friendship with the world?

Rachel Eliza Griffiths: While this book was very difficult, the reason why the grief and the trauma of the loss feels so difficult is because the love was, and is, so massive.

It often happens with loss—the first part of your grief is the closest thing to you, their physical death. But, if you can, go back before that part. It takes time and concentration, which you don’t have space for in the beginning. For me, it was like diving into water, getting deeper beneath the surface. You can look up and barely see where you came from. But you feel that the love between you and that person just keeps going.

NS: There’s a journey of getting past the breakers to that ocean of love.

REG: Yes. One of the ways that I got through the breakers was finally being curious about my grief. I’m thinking now of the promise that Aisha and I had made to visit the archives of our literary foremothers, to do that pilgrimage together. So, after Aisha’s passing, rather than feel like, “Well, I’m not gonna do that now,” I thought, no, now I must do it because I didn’t have anything else to hold on to. I was drowning.

Grief can often feel very passive, like being swept along, especially in the beginning. There’s no control. Maybe because I’m looking at the ocean right now as you and I speak, I remember feeling like I was locked inside a riptide. At some point, I began to think about what I could do, in terms of an action. I began with some questions. What did Aisha and I love? What did we care about? What mattered to us? Different things started to sprout and to grow from that.

NS: Realizing your grief is on a different timeline than others is such a real and unsung part of grieving. I think this is especially true with someone like Aisha. So many people feel an intimate connection with her. Thinking about your journey to owning your timeline, when did you feel ready to write about this? Was that even something you had the luxury of thinking about, being “ready” to write?

REG: I don’t think there was a moment when I felt like I was ready to write. My writing was an effect of the panic that I’d start to forget our memories and their textures of our relationship. Because that invariably happens to some extent.

Grief can often feel very passive. I remember feeling like I was locked inside a riptide.

The memoir really began with a lot of questions. Not even, why did this happen? That’s like a “breaker” question. You have to get far beyond that to something more like, how did this love begin? How will it go on? How will I survive?

There’s a clip where Toni Morrison talks about not surviving whole. Something happens to you, but you don’t survive whole. What you can do is go forward with a kind of elegance. Elegance and a deliberate energy about not surviving whole. Morrison doesn’t say that means you’re wounded or less, but I was so deeply wounded. I once had a muscle, many poets do, where poets are asked to stand and hold the line of humanity in the face of loss, injustice, violence, grief, war, fear, and so on. In this instance, which was so personal, I couldn’t hold anything.

NS: Thinking about where the love begins brings me to you and Aisha coming up as writers together. While you and Aisha met in an MFA program, you both sought and found an enduring writing life that was not defined by the program. I love the scenes of your early years in New York together. Can you talk about this part of your sisterhood?

REG: Prior to Sarah Lawrence, I was much more of a loner. When I met Aisha, there was this joy of having my first adult Black girlfriend sister, that kind of joy of discovering someone who feels like kin, that you’re not alone. Aisha and I were deeply committed and deeply serious about developing ourselves as poets. It wasn’t just the work on the page. Poetry is a way of living. You’re expanding. Everything’s at stake. It’s not just sitting down at the MFA table. There’s not just one table.

NS: I remember spending time with you and Aisha in those years in West Village, dancing. Maybe the little sister in me was activated, but it always felt like we were doing something important, like something really important was happening.

REG: Suddenly, I remember the image of James Baldwin dancing with Lorraine Hansbury in somebody’s living room. The joy! Or the photograph of Toni Morrison’s glowing smile as she’s dancing with her arms up in the sky at a party. I love that photograph of Amiri Baraka with Maya Angelou at the Schomburg. They’re dancing on the sacred site of Langston Hughes’ ashes, you know?

Aisha and I could explore all these different spaces and know the functions of those spaces and where they overlapped. I remember nights where you could hear a pin drop sometimes at Bar Thirteen during a Patricia Smith reading. And then other times when you were encouraged to holler, to participate in roll call. All of these spaces were necessary. You could go to a KGB Bar reading, that’s a certain kind of environment. You could go to Louder Arts at Bar Thirteen. You could go to Cornelia Street Cafe, which no longer exists, and that’s a different kind of environment. We would go to all of them.

There were years where the pace of life in New York was heartbreaking. We had to hustle. We were teaching classes from 8 am to evening. We’d call each other, “I’m on the bus,” “I’m getting on the train,” “I’ve got to go to office hours,” “I haven’t gotten a moment to eat yet today.” It was work. The labor could wear you down. To defy the labor, to resist feeling beat down, we’d have to find the party. For us, the best part of the party was the music.

NS: Let’s talk about the music. “Love language” is a corny phrase but anyone who knows Aisha knows music was her love language. It’s there in your “meet-cute” where, grabbing a drink at a campus bar, you and Aisha stitch together life histories in jukebox songs. You write, “Music, good music, was our language.” Can you talk about the place of music in your relationship?

REG: I remember a time when there would be such shyness and risk in sharing your playlist with another person. It was like inviting them into your brain, into your whole being.

Poetry is a way of living. You’re expanding. Everything’s at stake.

The day that I met Aisha, we were immediately offering each other mixtapes. Throughout our friendship, we’d send each other music at all times. Here’s a praise song; here’s a song for the morning; here’s your birthday song; here’s an IDGAF anthem; here’s an I know you’ve had a really rough week song. Here’s a Deep Breath song. Here’s a song to hold you up in joy.

Sometimes, you can get into the patterns or rhythms of knowing someone and their tastes. But with Aisha, you could get really surprised by what she might play.

NS: Oh my god, yes. I have that memory with Aisha—talking about The Human League together.

REG: Aisha loved The Human League, right? And she was from Nashville, so the blues and country too. Aisha could go in all directions with music. Her musical intelligence is in all her poems. It was in her physical voice. It’s also how she often held a vibrational space with people. Aisha could listen to people, listen to their songs, and then offer almost like this expanded version of their song. The extended album cut. She’d add in those things that you were trying to ask or think about or feel out. Aisha put in extra lines for you. And you’d think, oh yeah, that’s what I was missing or oh yeah, you filled the song in for me with what I needed, thank you. It was so beautiful.

NS: I want to sit with that for a minute—the vibrational space that she held, that your friendship held. I want to think about that in relation to the ongoing health conversation you had together. Can you speak to what it meant to create this space?

REG: We really talked about everything. How could we not talk about our bodies particularly as Black women? For example, Lucille Clifton’s work has so much to do with her body, and the bodies of her beloveds—her mother, her daughters, her children, and Black people. Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, and Gayle Jones were all writers who wrote of Black women’s bodies in ways we admired. Sonia Sanchez continues to center her body and its dignity.

Sometimes, while writing, you can almost feel like you’re out of your body because of your mind, your spirit. You’re in this other space. But it’s your body through which you’re receiving language, stories, testaments, tears, laughter, all of it. The entire human collective is in you in that instant.

I remember how Aisha loved talking about her hair and getting her haircuts, curling her hair, deep conditioning her hair, which was beautiful. I miss her hair. It was such a part of her. We were both into tending our eyebrows. You know, things with women are not just a simple conversation.

NS: In this book you come out as being diagnosed with Dissociative Identity Disorder, which is as much an in-the-body as it is an out-of-body experience. Do you think that dissociative identity disorder puts you in touch with your body in ways that you might otherwise not be?

REG: When I was younger, I didn’t have much education about mental health. I just had panic, anxiety, so much shame. I didn’t even hear about the term, “Dissociative Identity Disorder,” until my late twenties. Seeing how DID is often portrayed is really devastating to me. The older language for it orbits multiple personality and horror movie narratives, like Jekyll and Hyde. That’s not an accurate representation. I’ve rarely seen any accurate representations. Even people in psychotherapy don’t really have a standardized language for it and have different opinions about how DID works.

I started Sarah Lawrence in my 20s barely a few months after a very severe suicide attempt where I was in a psych ward. Mental health is extraordinarily important to me. It’s such a private, intimate thing yet it affects every behavior, it affects everything, and I’ll always be interested in it because I have to maintain an active daily practice that pays attention to my inner life beyond writing and art.

NS: It seems like you and Aisha created a space where your health histories became legible. It makes me realize that this book, as much as it’s about grief, and it’s extensively and beautifully about grief, is about the choice to live. I think that you and Aisha together made a choice to live, from the beginning. And that choice flows through the book.

REG: Yes. I think coming from where I was coming, arriving at Sarah Lawrence and just needing to heal—in some way, the last thing I should’ve been doing after being hospitalized was putting myself in a graduate program for creative writing. But it was the best thing to do. When I met Aisha, I felt a new hope in her presence. We wanted to live fully. I feel that way now, wanting to live fully. I believe Aisha still lives now in the ways that so many of us continue to read her poetry and share our memories of our times with her.

NS: This book is both Aisha’s passing and Salman’s attack, that compoundedness of trauma. The way you and Salman care for each other is really special. I was struck by that moment in the book when you say that you and Salman, against your will, realize you’re new people in a new life, a second act becomes a third or fourth. What did meeting each other anew teach you?

REG: When I met Salman, I was at a crossroads in my life. It was in the wake of my mother’s death. I was forced to think about who I was at that moment, aware that my identity was suddenly detached from what I thought I’d been before in roles as a daughter, sister, wife.

It’s very hard to have a book that you write against your will.

Our connection was one of the things that immediately made sense to me. I felt like I was home. I thought, Oh, I don’t have to explain. I don’t have to defend. I don’t have to convince. That was a new, almost uncomfortable feeling because I was used to everything being difficult and overthinking. Suddenly, it was just like, “You’re a grown woman, what do you want?” I wanted a life with this person. It was clear to me.

I also want to go back to the two events occurring with Aisha and with Salman that form this book. It’s very hard to have a book that you write against your will. A former version of me would’ve tried to keep writing more poems, or another novel, or concentrate on visual art and not tell anyone how much I love these two people, not tell anyone how vulnerable I was as a child, or what it’d been like as a young writer going through different experiences and hardships.

Both Aisha and Salman will always be in my work, not necessarily explicitly, and not because of the grief and the trauma. It’s about the love that I hold and carry from each of these individuals.

NS: I always say, “I’m bad at grief,” even though that doesn’t make much sense. Sudden death is uniquely hard to grieve. You write at one point “I don’t need to memorize Aisha’s dying . . . I need to memorize how fearlessly Aisha shone.” I was wondering what advice you have for others who have incomplete endings?

REG: I think most people are bad at grief, right? It’s such an intimate space. And there’s nothing identical in the grieving experience. It’s so surreal and distinct, relative to the loss. When you experience ambiguous loss, you’ll spiral out to sea or space. You must figure out how to stop breathing into what you can’t know. You must breathe into what you do know, which is love. Because love is what is going to rescue you.

I tried to intellectualize my experiences but I learned that for me, I needed to focus on caring for my body. For example, I have a regular practice of immersing myself in sound baths. Vibrations in that environment will often do more for my brain fog than a 200 page book. Reading a book involves a cognitive engagement while the sound bath is doing something deeper that I can’t overthink. I have to surrender and open my body to it.

NS: It’s funny that you say that because we’re writers, we are word people. I think the writing actually comes from that sonic vibrational space, you know? This book really feels like you share a vibrational energy with us.

REG: I could never write this book now. For me, it’s still astonishing that I wrote it at all. I don’t know what I’ll do next, but I know that I gave everything to The Flower Bearers.

Hopefully the book gives its gifts to others. Because I know that there are others grieving and coping with trauma and identity. In a way, this book has already helped me keep going. It is enough. That’s something too, showing up for past selves and past lives. It’s enough. I miss Aisha. I want to call her. I want to talk to her. But it’s enough, what I had for seventeen years. It’s enough.