Interviews

Laurie Sheck & The Ghosts of Venice

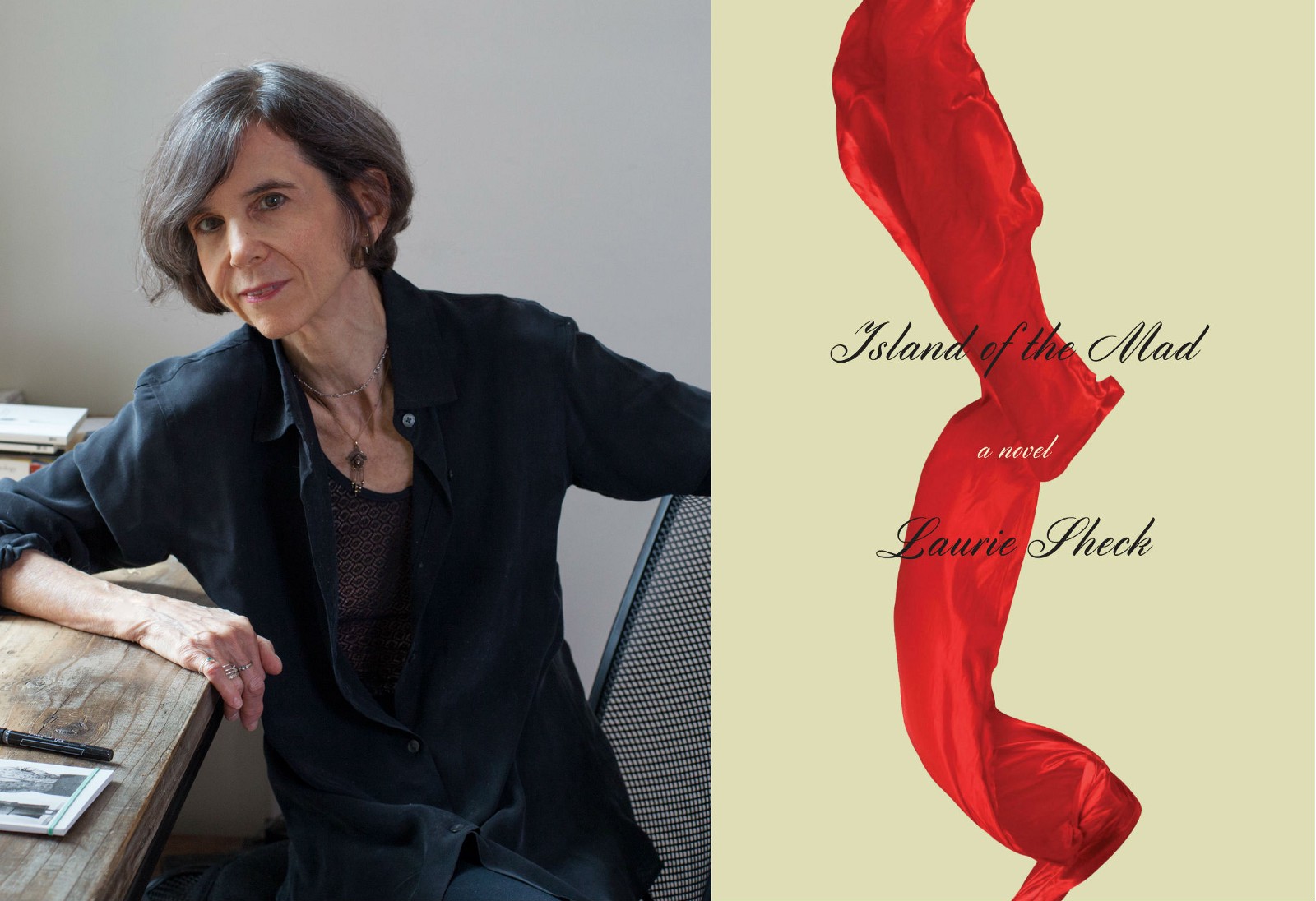

The novelist and poet on communing with Frankenstein’s monster, Dostoevsky in chains and breaking free of traditional narratives.

Laurie Sheck is the author of five books of poetry, including Willow Grove, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. In recent years, however, Sheck has written two genre-bending novels to great critical acclaim, including A Monster’s Notes (2009), narrated by Frankenstein’s monster, which the Washington Post described as “a remarkable creation, a baroque opera of grief, laced with lines of haunting beauty and profundity.” Her most recent work, Island of the Mad, features more of Sheck’s unique approach to novel-writing, in which the narrative consists of notes from a hunchbacked man’s journey to Venice to seek a notebook. The man ends up on the island of San Servolo, the site of one of Venice’s isolation hospitals, and there he encounters a number of characters, some historical, some fictional, including Pontius Pilate, Bulgakov’s Margarita, Titian. But the character who haunts Island of the Mad is Dostoevsky, whose suffering makes for a timely reminder of what happens to art under despotic regimes. Soon after the novel’s release, I corresponded with Sheck over the course of two weeks. We discussed Dostoevsky’s terrible trauma, exile, illness, Frankenstein’s monster, and the “radically ungraspable” nature of today’s technology-soaked reality.

Lorraine Berry: Neither of your novels follow a traditional narrative structure. Some have described them as a series of prose poems whose connections are as intricate as spider webs. Are you comfortable with that description?

Laurie Sheck: It’s intriguing to me that the issue of structure is initially framed in terms of what the books do not do. In a sense the scene is set against a background of what’s considered the norm — which would seem in this case to be traditional narrative structure. But which tradition? Whose? From where and when? For me, part of what books give us, and I think we become active participants as we read, is the enactment of a freedom of the mind, the whole being, or at least a keen striving for it, through the medium of language. And by freedom I don’t mean formlessness or being freed from constraints, limitations or one’s own narrowness. I think of freedom as allowing for a striving toward the genuine.

This freedom includes the liberty to explore anything that feels necessary, however fraught, confused, contradictory, including feelings of enslavement, sorrow, oppression, entrapment, as well as states that are more calming or joyous. If we use the word “text” do we approach a book with a more open, flexible curiosity than if we say “novel”?

The notion of genre has uses, but it also risks being reductive, misleading. Did Proust use traditional narrative structure? Did Melville? Did Dostoevsky? Sebald? Woolf? Certainly not Stein! Isn’t one of the joys we find in books the ways they’re sites of great diversity and idiosyncrasy. That there’s a kind of unbowed spirit.

Writing is deeply architectural. And as with architecture there are period styles, but also much that’s divergent, and some that’s totally outside the dominant framework. How does a text, like a building, grow out of its own particular necessities? How does it stay true to them, make them palpable? To me what counts is that a text is a site of vital becoming — imperfect, flawed — but its flaws are just as beautiful a part of its being as anything else because they’re genuine and necessary.

It doesn’t matter if I’m comfortable with how a book I write is described. My comfort is irrelevant. The book is a language-act, a world of language that came out of me, but I’m not its owner. I was a controlling, partly pushy, partly baffled participant in this process that involves language, and somehow the interaction between myself and the language, the books I’ve read, the art I’ve looked at etc., brought it into being.

In the case of Island of the Mad and A Monster’s Notes before it, I assembled for myself initial areas of fascination, in the earlier case Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and the ‘monster’ as well as the Shelleys, and now in Island of the Mad Venice and Dostoevsky, and then set forth as best I could to have an experience within the medium of language. How I came to this was hardly straightforward, but it involved a desire for a different kind of experience with language than I was having with poems, and a pretty deep dissatisfaction with what I’d been doing. It involved, as well, a period of illness, first mine, then my husband’s. Those things change you. I also felt a strong pull to do research that wouldn’t just inform the work from outside but become in itself an intrinsic part of the text. I was curious about the interaction of fiction and non-fiction.

Certain events had pressed down pretty hard on me and I wanted to think about how strong facts are, how brutal, how the imagination is real but so are facts you can’t change or break free of. Beyond that, I was pretty clueless. Certainly clueless about how I would feel and hear the various voices involved in such a pressing, sustained and immediate way. Their intense presences. I was just clueless about most all of it. All I knew was I was bringing to what I was doing my poet’s experience and interest in structure, in words, syllables, language on an almost cellular level. I didn’t label what I was doing — still don’t — I had no word, no category, for what I was writing. Somehow there seemed a kind of justice in that. Rough, not smooth. I see now how that very concern runs through both books, the interrogation of categories, assumptions, labels — In what ways do they harm, comfort, betray, mislead, seduce, promise? How do they reinforce particular thought patterns, privilege certain actions over others?

Berry: In several of your poems and in your two novels, you are engaged in relationships with other writers: Mary Shelley, Dostoevsky, Gertrude Stein, etc. How would you describe these relationships? And what called you to these particular writers?

Sheck: To live with these writers brings me great comfort. Through their work I am in the presence of these amazing questioners, these explorers. I feel very strongly Mikhail Bakhtin’s notion as set forth in his book on Dostoevsky and elsewhere, that a self comes into being in the process of active dialogue with others. And some of this dialogue is not through speech, but through the written word, through books. Books, too, are living, changing beings. The book is changing and I am changing. We both have unvarying identities, but there is also flux, shifting contexts, there are shadows, angles, time, space, history. When I was younger I felt a writer had a vision and that vision was expressed through their books and it was my obligation, my privilege, to see what they “meant,” to enter into their line of vision. But I think Bakhtin is right — the author is one player among several. How fully does the author know and control the work? What happens beyond intention? In a good book, a whole lot. The texture of human consciousness can be served by intention, craft, discipline, but that’s different from being owned or controlled by it.

Books, too, are living, changing beings. The book is changing and I am changing.

Even though I’m finished with Island of the Mad I’m still in the thrall of Dostoevsky. As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, to my mind The Idiot contains one of the most daring, tender, radically re-defining scenes in all of Western literature — the night when Prince Myshkin, vulnerable, epileptic, stays and comforts the murderer Rogozhin. Dostoevsky is criticized for dwelling on “cruelty,” the perverse etc., for indulging in the melodramatic, but in fact he is an astonishingly tender, compassionate, realistic writer. And so brave and intricate. Well, he was a genius. And as a person he was very brave and his biography moves me.

They all suffered. Even Stein, who seems so willingly combative, provocative, playful, jaunty, a real fighter — I read a comment of hers that’s stayed with me — I haven’t been able to find it again but I’m still looking —

She spoke about what it cost her and other artists to be up against so much ridicule and misunderstanding. It was said strongly but almost in a whisper, as if there were an element of danger in letting it out. And in Patriarchal Poetry she makes a kind of plea to be heard, part nursery-rhyme, part insistent command, to let women’s voices in, to let them be heard. “Let her be.”

Writing is both very lonely and not lonely at all. Everything that’s most hurt in me, most despairing, has found a home with these writers. And as Bakhtin pointed out so wisely, it’s not that I merge with them. Part of what makes the experience of being in their presence feel right and stringent, convincing, is that I can’t. I stand outside them. It interests me that Bakhtin developed his ideas about dialogism and the polyphonic novel — that is, the necessity of a self continually coming into being by being in the presence of others, an active, receptive part of an inter-change — under very isolated circumstances. That isolation partly brought him to this insight about connection. He lived in internal political exile in Russia and suffered with Osteomyelitis, a very painful, incurable infection of the bone he contracted in boyhood and that kept him periodically bedridden. Eventually one of his legs was amputated. Hardly any of his work was published in his lifetime.

There is a way these isolate figures — Bakhtin, Dostoevsky enduring an epileptic seizure, Mary Shelley’s abandoned “monster,” Prince Myshkin who ends up mute in a Swiss Sanitarium — all echo each other. I can’t imagine my life, my thinking, who I now am, apart from them.

Berry: How did you develop your style of prose? Had you written much prose prior to your career as a poet? What did you write as a young woman? A child?

Sheck: I always loved words. From the very beginning. Their sounds, shapes, how some letters seem shy or almost starving while others are brash, still others more cryptic, hard to decipher. But I was never a storyteller. From early on I was a mixture of concentration and distraction. The whole idea of learning, of having to learn and retain information made me anxious, at times to the point of panic. As a child if I tried to write a story I think I would have felt on some level I was being too overtly forceful, taking up too much space. Thinking was alluring but also frightening.

There must have been something about the contained space of a poem, so small yet immensely kinetic, partly secretive but secretly bold, that drew me. If I had any expectations at all, it was to spend my life within and among poems. It simply didn’t occur to me I would write anything, ever, that would be called a “novel.” It didn’t occur to me until it started happening.

I think largely in images, symbols — or I guess I should say I did. But I also felt like my brain was partly asleep, muffled. I felt my writing was quite limited. And I had many psychosomatic symptoms. For all I know my body was struggling toward a more expansive mental state to move around in, a space open to more of the world, to non-fiction.

I lived for a number of years with a painful neuralgia on right side of my face. Often the pain intensified and when it did it spread through my entire right side or further and all of me would stiffen. As many people do in such circumstances, I thought what a great gift normal everyday life is, just to have that basic sense of well being, to sit, read, work, talk with friends, make coffee. I’d been born into the middle class of a wealthy country without wars on its soil, and I felt I was squandering what I’d been given. How many people on this globe even have adequate shelter, food, sanitation? Not all that many. When the neuralgia was finally diminishing, and by then my husband was falling ill with a genetically-linked illness that lasted for four years until it started to burn itself out, something in me had finally sharpened. My desire to learn was intense. There were still a lot of glitches but also a kind of fierce, excited curiosity and determination.

My husband was very ill and in a sense I had lost him, had lost, certainly, our long, sustained conversations. For various reasons I picked up Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Before I knew it, it seemed the monster was always with me. I felt him, or my version of him. If I went to the movies he came with me. If I picked up a book he was reading it also. But he was with me in a way he could never know and that kept him lonely. I started to wonder what would interest him. If he could choose, what would he read? Soon I was pursuing various areas of investigation…or in part he was pursuing them through me. Maybe this sounds a little crazy, but it felt clear, systematic. I started taking notes — on genetic engineering, robotics, genetic privacy, the Geneva Accords, the nature of time, space, perplexity. These notes were in prose. And along the way I’d become fascinated by the Shelleys.

Before I knew it, it seemed the monster was always with me. I felt him, or my version of him. If I went to the movies he came with me.

Claire Clairmont, Mary’s step-sister, had run away to France with Mary and Percy. They were teenagers. Percy was the young, married father of two children. Claire eventually had a child, Allegra, by Lord Byron, who was taken from her and put by Byron in a convent where she died at the age of 3. Claire kept a journal; there was also a volume of her letters. Not to mention Mary’s, Percy’s, Mary Wollstonecraft’s, the Frankenstein manuscript’s first 40 or so pages overwhelmingly in Mary’s hand but Percy’s was there also. I was writing my way into all of this material. Just writing. And it was in prose. I found the interaction with facts thrilling. I tried to make each page justify its existence, while feeling my way forward. I paid a lot of attention to the felicities of chance, to the reality of a multiplicity of voices, to the integrity of the texts I was using. Nothing is more radical than the real. The prose seemed to open a way to being more attached to the world, less reclusive, it allowed a greater waywardness and questioning.

Berry: In Island of the Mad you include the details of a true story I had no idea about, I’m embarrassed to say. After reading it, I had to put the book down for a few minutes because it had made me cry. On page 214, you detail Dostoevsky’s enormous suffering in the Russian prison system. You said he was arrested but “confessed nothing Refused to be destroyed ‘by an empty word.” And one of the ways he was punished was that he was read the death sentence, dressed in execution clothes, and marched to the place of execution. At the last minute, he was given a reprieve.

The psychological terror inflicted on him just seemed unbearable. Do you have a sense of how he survived his experiences?

Sheck: It’s an astonishing story. His life was full of excruciating extremity. People said he always looked ill. You can see this in the photographs. But even in regard to this, Dostoevsky came in from an uncanny angle: “…a person does not always look like himself,” he wrote in his essay Apropos the Exhibition.

After the mock-execution at Semyonov Square he was sent to Siberia, to the prison camp at Omsk where he remained for four years (he’d been convicted of political sedition), and then served another five years in another part of Siberia in enforced military service. During his years at Omsk he wore five pound shackles on his ankles, as did all the prisoners. Joseph Frank’s magisterial 5 volume work on Dostoevsky’s life and work is one of the best books I’ve ever read on anything. All the details are in there, and much more. There’s a short book by Robert Bird that’s also very good as a basic overview.

The timing is somewhat in dispute, but it seems most plausible that Dostoevsky’s epilepsy started shortly after his arrival at Omsk, possibly triggered by the extreme shock of the mock-execution. Another member of that group afterwards went mad. After prison Dostoevsky was also for a period of time a compulsive gambler, which may also be traceable back to this trauma, and one reason her went abroad for a few years after prison was to escape his creditors. He wrote The Idiot, the book I explore in Island of the Mad, while in Geneva. At least he started it there. He finished it in Florence where he and his wife lived after the death of their first child, Sonya, who was born during the writing of the book and lived for only three months. They couldn’t bear to stay in Geneva after she died. They were both broken, and yet somehow he finished The Idiot. There are very strong currents of grief in that book’s second half.

Robert Bird writes of Dostoevsky’s radical doubt. I think that’s a good way to put it. As a novelist (as opposed to in his journalism) he questions everything, lets in all sorts of angles. Nothing is stable. One could speculate that trauma partly made him the great writer he became. There were many other difficult aspects of his life as well. In The Idiot Prince Myshkin speaks at length about the inhumanity of state sanctioned executions. He’s also epileptic — his whole being inseparable from disruption, extremity, unstoppable neurological events that come without warning and over which he has no control. Dostoevsky himself often felt humiliated and ashamed about his seizures. This shame was especially deep when one occurred at the very time his wife was giving birth to his daughter.

But extremity isn’t all negative. Dostoevsky wrote in The Idiot and The Possessed of the ecstatic aura that preceded the seizures. It lasted for just a few seconds, but that transcendent experience had a profound effect on him. So, too, living among the other prisoners at Omsk for four years, most all from much lower classes and from deprived and violent backgrounds, taught him things it’s hard to imagine he would have otherwise known. His experience at Omsk is most directly presented in House of the Dead but it infuses all his other work as well.

All of this is crucial to his ideas about realism. I mean, his biography is such that had a novelist written it, that writer could easily be accused of crossing over into the unbelievable. He deeply, deeply felt and understood how extreme and brutal reality is. And one part of what makes him so amazing as a writer is how along with casting an unsparing eye over everything he held his characters with such careful and abiding tenderness.

Berry: As I mentioned to you in earlier correspondence, I read an advance copy of Island of the Mad during the week that I had been evacuated from the barrier island where I live during Hurricane Matthew. I felt as if I were reading the perfect novel during that time period because of the theme of exile that plays such a large part.

I also know from your writings that you have been a quasi-Luddite when it comes to adopting the technological “wonders” of the past 40 years. As a writer, do you feel a sense of exile from a culture that seems less interested in the written word and more interested in the whizz-bang of wherever technology is leading us?

Sheck: Despite not owning a smart phone (though I plan to get one) and never having sent or received a text message, I find a lot of the new technology and specifically what’s happening with the internet, exciting. Even if the culture is moving and changing in ways it’s hard for me to relate to or understand, in certain ways I’m following as best I can.

Certainly the internet’s been enormously important to me as a writer. I can’t imagine I’d have written my most recent books without it. It’s given me access to all sorts of information, and just as importantly, it’s modeled and enacted a web-like structure, and taught me a great deal about movement, linkage, recombination.

But it’s also overwhelming, and in our world as it is technology is inextricable from danger, aggression, mistrust, deceit, annihilation. I’m thinking now of Eliot’s “human kind cannot bear very much reality.” Given our century our various terrors are, and will be, wound up with technology, especially as ours is a very powerful, militarized, crudely profit-driven nation.

But so many of our beauties are wound up with the technological as well. I can go online and see Emily Dickinson’s manuscripts with their variations uncensored, intact. I can see Virginia Woolf’s typed and handwritten drafts. Or take another manifestation of technology — glowing screens. While it’s true they can be used in garish, disturbing ways, as in Times Square, at the same time architects are turning to them as an almost moth-like, sensitive alternative to walls — more vulnerable than drywall, more skin-like, less imposing, static, monolithic. So in feeling and tone they’re kind of like Bakhtin’s vision of the dialogic — porous, flexible, receptive boundaries, but embodied in the material world rather than in language.

I live in downtown NYC, I was here during 9/11. The smell of it, so many things, the hundreds of ash-covered people walking past my building, the sky weirdly quiet, no cars, no buses, no mail delivery, xeroxed faces of the “missing” on buildings and fallen onto sidewalks, all of that’s so vivid. And now every year in September two faint, blue columns of light are cast into the sky as a memorial. They look frail, dignified, almost unbearably gentle. In this way technology makes possible the apprehension of the deepest human feelings.

I find really interesting Giuliana Bruno’s exploration of the virtual in her book Surface, as she works through the ways in which surfaces are also depths. Screens, computers, smart phones, 3d printers, none of them invented human sadness or alienation. Like so many others, I think the bedrock cruelty in our culture lies elsewhere, in economic, racial and other injustices, and also in the belief in meritocracy which turns the gaze away from where it truly belongs, which is on inequality.

To be living now, for me, feels kind of like a strange mixture of closeness and distance, as if skin is flesh but at the same time virtual.

I don’t own a TV, I don’t really understand social media, though these words I’m typing are meant for the internet. To be living now, for me, feels kind of like a strange mixture of closeness and distance, as if skin is flesh but at the same time virtual. A few clicks on my laptop and whole stretches of outer space appear, captured by the Hubble telescope. There are lunar events in real time. Astronauts describing the smell of outer space — distinctly metallic but mixed in with something that’s acrid, burnt but also un-nameable. It all goes back in a way to what Dostoevsky knew about reality and never pulled back from — how extreme it is, how radically ungraspable.