Books & Culture

LITERARY ARTIFACTS: Finding the Future

by Kristopher Jansma

Each month in the Literary Artifacts space, writer Kristopher Jansma writes about his encounters with rare books, writerly memorabilia, and other treasures in New York City and around the world, hoping to discover how the internet age is changing the face of literature as we know it.

I arrived at the Centennial Exhibition at the New York Public Library’s Stephen A. Schwarzman building, fully expecting to get lost in the past. But there, above the iconic stone lions, Patience and Fortitude, I was surprised to see a large sign inviting me inside to “Find the Future”.

Surely the slogan was meant to be inspiring, but its stark font filled me with dread. The future was what kept rushing at me through my Twitter feed: the threat of more hurricanes, another election season, the development of an HBO adaptation of The Corrections. I wanted to walk around in a beautiful Beaux-Arts building and examine the belongings of writers long-dead. I wanted to forget what century it even was.

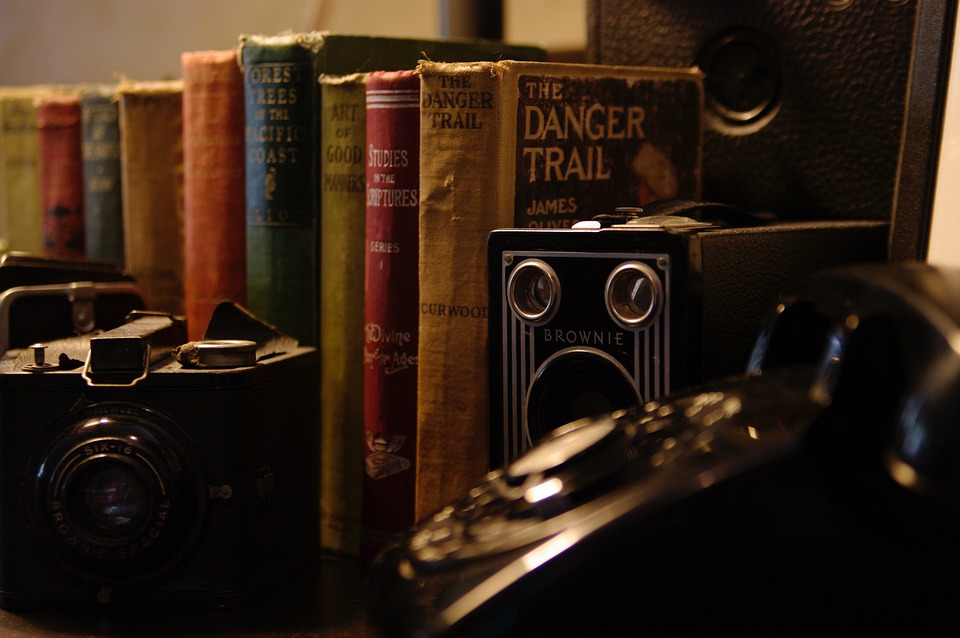

The exhibit did not disappoint. Inside I found a massive room filled with artifacts, literary, historical, and otherwise: Columbus’s letters, Audubon’s “Birds of America”, and Kepler’s first model of the solar system. But then I noticed a gleaming white MacBook sitting under glass in the center of the room, quietly displaying the New York Times homepage. Was this what they’d meant by “Find the Future”? Beside the laptop sat two small lumps of clay, etched in cuneiforms that were over 5,000 years old. The earliest known human writing looked sad and insignificant when placed next to the sleek, glowing machine.

A nearby sign explained that “as the Internet makes information increasingly easy to obtain, and more experiences become virtual, direct encounters with the Library’s books, manuscripts, prints, photographs and objects reveal the collections as an indispensible public resource.” A teenaged boy came up and pressed his face against the glass, staring longingly at the laptop. He did not seem to want virtual, direct encounters. It looked like he wanted to check his email.

How, exactly was the Internet making libraries more indispensible? It seemed like wishful thinking to me. Had I been able to hop onto the MacBook, a little Googling would have turned up a growing list of shuttered libraries, all across the country — the result of budget cuts and the waning interest of communities and schools. Twelve libraries closed in Charlotte. More in Los Angeles and Portland. Highland Park and Troy, Michigan, and Gary, Indiana . What would have taken hours in front of a microfilm machine or digging through huge stacks of periodicals, took me minutes with the Internet. And I wouldn’t have even been able to find this YouTube Video of an old man weeping over the closing of the library in Philadelphia where he’d been going all his life.

If that was the future, I didn’t want any part of it. I pushed on, deeper into the exhibit, and quickly succeeded in distracting myself with the past.

First I came across a case containing Virginia Woolf’s walking stick. The caption explained that her husband, Leonard, had found it floating in the river where she’d drowned herself. Beside it was the entry from her diary, on March 24th, 1941, written four days before her death. It was the last entry she’d ever written and it made me a little weak in the knees, and not only because I had to lean closely to decipher her handwriting. “…had been killed in the war… 3 covered chairs with knitting in her hands… And then there was nothing. … I can’t tackle them (but) enjoy having them…” The jaggy words made me wonder how even her biographers could be sure what she’d written in that final entry. And all the while there was just this cane, hovering there — quite possibly the last thing she touched before death.

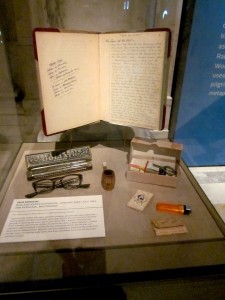

Nearby I found a case containing an assortment of Jack Kerouac’s possessions: a pair of his glasses, a harmonica, and a corn-cob pipe. Just the things he carried that day. A package of Valium with a note rubber-banded around it. An orange BIC plastic lighter and a package of Zig Zag rolling papers. It’s clear that these weren’t treasures of any kind, just what happened to fall out of his pockets on some transient day. And for a writer whose whole life was about transience, this is also powerful. No room for valuables or treasures when you’re on the road.

All this sat beside one of his open journals, where he detailed a crossing to New Jersey with Ginsberg . Feeling “haunted by something I have yet to remember…” he wrote, “seldom have I been so glad of life.” On the inside cover he had composed a short “Travel Song” and standing there, I can imagine him and Allen singing while cruising through the Holland Tunnel at dawn. “Ain’t no home for me… Home I’ll never be…”

Suddenly, I was bumped by a young man with his camera out. He looked down at Kerouac’s journal, snapped a photograph, and moved on — the whole thing took less than two seconds — and then he was on to the next object. I was stunned, even angry. Here he was, effectively downloading the exhibit. Kerouac’s Valium. Click. Woolf’s last words. Click. Skimming through it like an RSS feed. The Google approach to museums: grab it all and search it later.

I was upset, but as I moved along through the exhibit, I also began to get overwhelmed. There was so much to see — a draft of Eliot’s The Wasteland, covered in Pound’s notes. Hemingway’s Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech, composed on the inside cover of a book, because he’d written it on the fly, poolside, and it had been too windy for paper. I’d read the speech myself many times and was quoting from it in my novel, but I began to wonder… if I hadn’t been a literary nerd when I walked in, how would I know why any of it mattered? There was no context for any of it, except what you brought in with you.

All the literary things thrilled me — a typewriter belonging to e.e. cummings (I was sad to see its Shift key had not been removed) and Charlotte Bronte’s traveling writing desk. Charles Dickens’s letter opener, to the end of which he’d attached the preserved paw of his cat, Bob. But I couldn’t really understand the significance of the pop-up books on the neighboring wall. Malcolm X’s letters didn’t do much for me either. My only reaction to seeing a page of a Beethoven score was that it was written so sloppily that he must have been a genius simply to read it. I was amused by the very first printed version of “The Star Spangled Banner”, with a typo at the top describing it as “A Pariotic Song”, but I needed more. To appreciate any of it, I would have to dig deeper. I needed to Google.

And I wanted to see what Woolf’s diary really said, and I wondered if Kerouac’s “Travel Song” was his own concoction or something he’d heard on the radio, or on the road somewhere. Soon, I found myself reaching into my pocket for my own camera. I took a couple of shots, quickly, in case the guards came by. I wanted to remember everything I’d seen. There was so much I did not yet understand.

On my way out, I once again read the words by the entrance. Rather than render libraries irrelevant, could the Internet really help them become more important than ever?

The New York Public Library already offers eBook rentals which can be downloaded directly to an eReader and “returned” or renewed like any physical book. They have a Tumblr Page and an iPad app (The Biblion) and their website offers a free eBook of “Know the Past, Find the Future”, which contains essays written by celebrities from Stephen Colbert to Yoko Ono, regarding their favorite NYPL items. The website’s “Find the Future” section has loads of fun extra information on the artifacts in the show and a “Centennial Quilt” that you can interact with, because nothing says the future quite like quilting! For kids, there is an interactive Find the Future Game, where they can “activate” the various artifacts and contribute to an evolving story written entirely by other children. It is an impressive embrace of technology, and it hasn’t gone unnoticed. The Atlantic Monthly recently cited the New York Public Library as a shining example for all businesses, of how to utilize social networking and websites to keep their brand strong. And yet the NYPL itself was only barely spared a $40 million dollar budget cut this summer, following two previous years of major cuts, despite usage of the library going steadily up, and a huge increase in the services that they offer.

Leaving the exhibit, I felt certain that they were on the right path. Technology can be a distraction, but it can also be a tool, just as libraries can not only preserve the past, but inspire the future. As NYPL President and CEO, Paul LeClerc, explains, “many generations have already ‘found the future’ by exploiting the Library’s massive collections to explore, discover, invent, and to create new knowledge and new works of the imagination.” As someone who has tapped away at my share of keys under the stunning ceilings of the Library’s Rose Room, I can’t agree with this sentiment more. Being there reminds you of why any of us might strive for greater things. Who would bother making history, if it only had the lifespan of a mouse-click? Indeed, in a neighboring gallery, you can see a collection of great works written there, at the Library, and you can browse these on mounted touch-screens, replete with information about how these authors used the robust, and free resources of the library to complete their works.

It’s inspiring, to see the physical objects made me think about the physical beings that had left them: these iconic figures were just people, with wobbly-hinged glasses, an urge for a smoke, and balance problems. Seeing their odds and ends makes you feel even closer to them, and their contributions. Standing there, you are tempted to imagine what might go into the NYPL archives next. David Bowie’s make-up case? A lock of Toni Morrison’s hair? John Updike’s Sunday shoes? Maybe something of yours?

If it is wishful thinking, at least it’s a future worth wishing for.

***

— Kristopher Jansma is a writer and teacher living in Manhattan. His debut novel, The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards will be published by Viking Press in 2013. He has studied The Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University and has an MFA in Fiction from Columbia University. He is a full-time Lecturer at Manhattanville College and also teaches at SUNY Purchase. Recently, his short story “A Summer Wedding” won 2nd prize in The Blue Mesa Review’s 2011 Fiction Contest, judged by writer Lori Ostlund. His essays and fiction can also be found on The Millions, ASweetLife.org, The 322 Review, Opium Magazine, The Columbia Spectator, and The (Somewhat) Complete Works of Kristopher Jansma. You can also find him on Facebook.