Books & Culture

Literature Needs Angry Female Heroes

Looking beyond Plath and Woolf (and their characters) for models of managing depression

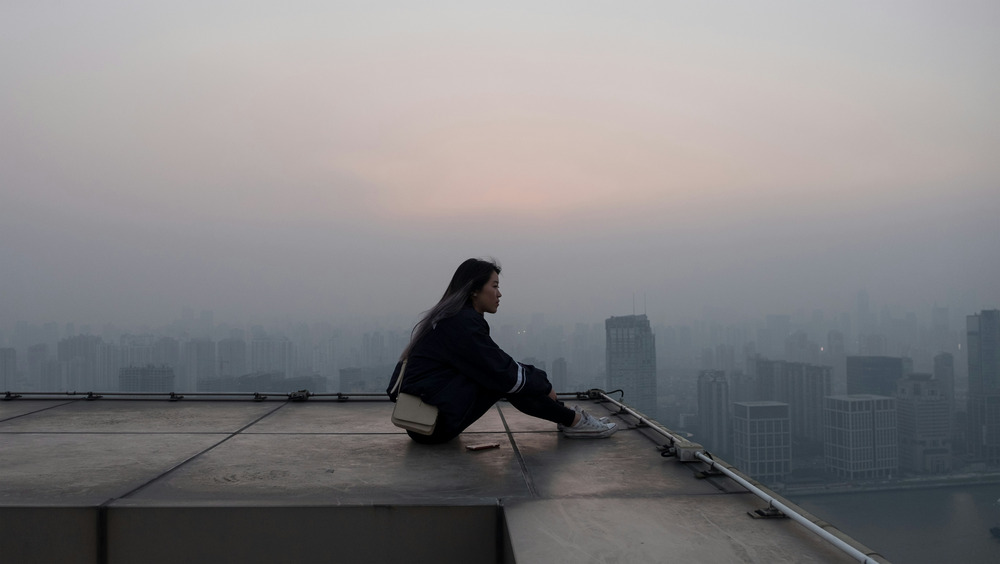

About a year ago I found myself in a depression. It came like all the clichés said it did. Sometimes like a fog, the air thick to breathe and hard to walk through. Sometimes like a rain cloud, hanging over my head and following me from task to task like a cartoon, the threat of rain worse than rain itself. Worst, it was like waves crashing over and over again, no lifeline of “better days to come” or “it gets better” or “count your blessings” enough to pull me up from under each cresting wave of failures, days spent kicking and kicking, and never breaking the surface.

I knew what it was for a long time, but I refused to name it for fear of appropriation, stealing from people who suffer from “real” mental illness. After all, I tried to rationalize, if my depression had a reason then it wasn’t really depression. If I was able to force myself from the bed I just wasted twenty minutes crying on, it couldn’t be real. If I hadn’t hit bottom, it couldn’t be real. Fighting against it to do all the things I needed to do was exhausting and left me physically sore, aching muscles and a pounding head, but the only alternative was giving up and giving in completely so I forced myself to do them. The fact that I could pantomime my way through the steps to complete each made me feel like I couldn’t possibly be actually depressed.

I knew what it was for a long time, but I refused to name it for fear of stealing from people who suffer from ‘real’ mental illness.

But that didn’t stop me from crying, every day, in the morning on the subway, on the phone when my parents called to check in.

I was tired all day, but I couldn’t sleep at night.

I finally called a therapist to set up an appointment, but she informed me she was going on maternity leave in a week so she was not taking new clients. She gave me some recommendations and asked if I had any questions. I was already crying in my workplace’s communal kitchen, hastily wiping tears that I was sure everyone could see anyway.

“Do you think it’s worth it to seek outside help?” My voice strained, and I could tell by her soft assurances, that, yes it was, she knew. I just needed someone so badly to tell me it was not all in my head, that I was not crazy, that something was wrong and I couldn’t make it right just by the force of my own will.

I tried what had so often brought me comfort in childhood: finding a character in a book who suffered as I did, and emulating her triumphs. I read The Bell Jar and thought about Plath and her oven; I read Mrs. Dalloway and thought about Woolf with her pockets full of stones. I wanted to identify with these women, to feel a spark of similarity or at least a dull ache of familiarity in my chest, a “misery loves company” type of understanding.

I read The Bell Jar and thought about Plath and her oven; I read Mrs. Dalloway and thought about Woolf with her pockets full of stones.

But it didn’t work. Because while I felt depressed like these characters, they did not feel angry like me. Literature made their depression elusive and magical.

There was Plath’s Esther, falling into her depression in the way good girls do: quietly, without a fuss, self-blaming, self-reflecting. She chastises herself for her emotions, holding herself responsible for not feeling the same excitement at her magazine internship that the other girls do:

“I guess I should have reacted the way most of the other girls were, but I couldn’t get myself to react. I felt very small and very empty, the way the eye of a tornado must feel, moving dully along in the middle of the surrounding hullabaloo.”

Esther’s depression was one of stillness, frozen, and even in the darkest throes of it, was tied to an inherent sense of self-worth. Even her oft-quoted passage about the fig tree, a touchstone in writing about depression, failed to ring true for me, her sadness manifesting from the abundance of choices before her, where my pickings seemed slim. “I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and go black, and one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet” she says, reflecting on all the possibilities her life could be in a way that made me feel a hollow emptiness.

Like Esther, Woolf’s heroine, Clarissa Dalloway, was also frozen in her depression, but managed to make a choice, to eat her depression, hide it deep within herself, never to be acknowledged. In the privacy of her bedroom after learning of a young veteran’s suicide she reflects:

“…she felt somehow very like him — the young man who had killed himself. She felt glad that he had done it; thrown it away. The clock was striking. The leaden circles dissolved in the air. He made her feel the beauty; made her feel the fun. But she must go back. She must assemble.”

Clarissa, for all her understanding and kinship towards the violence of depression and the demons that would cause someone to end their life, will still return to her party, will still smile at her guests, will still remain the upper-class woman she’s known as. She will experience her depression, but only in solitude. In the greater world, she will bury it.

These women, these authors and characters, are exemplars in literature exploring depression. Esther and Mrs. Dalloway are our archetypes — the characters I based my understanding of depression on. They are described as beautiful, sad things, with pale white faces that hide their true turmoil. Characters who will either soldier on bravely in the face of this illness or at least do so until they no longer can. They are the characters authors model their own depressed characters after: mysterious, beautiful, unknowable.

Authors like Jeffrey Eugenides. His novel, The Virgin Suicides, has become a modern classic exploring the depressive minds of young women. The boys in the book, acting as narrator, reconstruct the Lisbon sisters as sad nymphs with alluring stares and blond hair. The boys lament how it was always the same with the sisters, “…their white faces drifting in slow motion past us, while we pretended we hadn’t been looking for them at all, that we didn’t know they existed.” Even these girls (Cecilia, Lux, Bonnie, Mary, Terese) who unlike Esther or Mrs. Dalloway, succumb to what should be the horrible, unimaginable, messy endings of suicide in their narratives, are presented with a kind of glowing reverence, an untouchability, as if their depression made them unicorns in our world of mere horses, tragic creatures to be remembered as “carnal angels,” not even human in their deaths.

My depression is not this. It is not malaise or exhaustion or ennui.

My depression does not feel passive. It feels firecracker angry, seething just below my skin, ready to be set off, activated against the world.

It is a depression of hopelessness, but not the hopelessness of wishing for something else, of wishing for something more. It is a hopelessness that’s far more sinister. It is the feeling that you did everything you were supposed to do and still find yourself empty and unfilled, a realization to the broken promises of the world. Society makes promises, unspoken contracts, particularly with women, for what it deems acceptable and appropriate, rules that restrict you to a rigid path of being: be a good girl, don’t make trouble, don’t get into trouble. Want what we tell you to want, get what we tell you to get, and you will be rewarded somehow. Society spends our whole girlhood telling us to keep our heads down, to be ambitious but temper it with poise; don’t intimidate, don’t dominate, don’t get agitated or annoyed or visibly upset. Want the husband and the child and the home (and it all) but for God’s sake never act like you want it.

Then, they promise, you will be satisfied.

But I’m not satisfied. I don’t know what to do with the academic degrees I earned. I don’t know if I want the babies my body is running out of time to carry. There are terrifying moments when I realize my parents had already bought a house and had my older sister by my age. I feel empty. I feel owed. I ignore the gnawing fear, like a starving stomach turning on itself, that I will never be satisfied.

My depression does not feel passive. It feels firecracker angry, seething just below my skin, ready to be set off, activated against the world.

I oscillate between bouts of depression that mute the world and anger that leaves me screaming, embarrassed afterwards because I’m sure people in my apartment building’s lobby can hear me cursing and pounding the walls. The anger lives just below the surface, like a racehorse at the starting gate, threatening with each slight, each unfulfilled promise to take off. Esther did not scream at Buddy; Mrs. Dalloway did not snap at her friends and family; the Lisbon sisters did not wake up with raw throats and red-rimmed eyes from crying after a panic attack. But I did. And try as I might, I could not find myself in the classic texts of depression.

The Damage of ‘Crazy Ex-Girlfriend’

Then, one day in my building’s laundry room, I scanned the discarded books meant to help people pass the time. Almost on a whim, I picked up The Woman Upstairs by Claire Messud.

And I discovered the literary doppelganger I’d been aching for.

Much has been written about Nora, the unlikeable narrator of Messud’s novel, mostly revolving around the fact that the woman, to reviewers and readers, is particularly unlikeable. Messud has consistently defended her Nora, with a fitting response to a Publisher’s Weekly interviewer about if she (Messud) would like to be friends with Nora: “Would you want to be friends with Humbert Humbert?”

Nora, a fortyish single woman with no children, has an intense inner monologue throughout the book that consistently juxtaposes the display version of herself, the dutiful daughter, the dependable schoolteacher, that intangible, unreachable “good” girl all women are familiar with. Stretches of her dialogue feel as if she is speaking directly to me, validating my thoughts, reassuring me, no you’re not crazy, you did it right, you played by their rules, you are owed.

Stretches of her dialogue feel as if she is speaking directly to me, validating my thoughts, reassuring me.

Nora wastes no time pussyfooting around her anger, her very first lines in the novel: “How angry am I? You don’t want to know. Nobody wants to know about that.”

Nora’s anger fans my own, a fire of kinship that continues throughout the novel. Nora isn’t necessarily wronged, per se, except one whopper of a betrayal at the end, but that doesn’t keep her slow-boiling rage from simmering throughout the book’s pages. She’s mad not necessarily at decisions she made but at decisions she was forced to make, giving up her passion (art) for a career in teaching, losing her mother, her quiet, small life. She rants:

“It was supposed to say “Great Artist” on my tombstone, but if I died right now it would say ‘Such a good teacher/daughter/friend’ instead; and what I really want to shout, and want in big letters on that grave, too is FUCK YOU ALL.”

And though she understands she played some part in making this life she hates, she can’t figure out what she did wrong, what she did that sent her into this depressive anger:

“I’d like to blame the world for what I’ve failed to do, but the failure — the failure that sometimes washes over me as anger, makes me so angry I could spit — is all mine, in the end. What made my obstacles insurmountable, what consigned me to mediocrity, is me, just me. I thought for so long, forever that I was strong enough — or I misunderstood what strength was.”

I recognized this rage at not understanding what you’ve done wrong, this frustration at the unfairness: doing what you were told was right and still feeling like your life is somehow wrong. In the end, she lumps us, all the women with this ineffable feeling, together and I nearly weep with relief at what she understands, the exhaustion of fighting an invisible opponent society swears you are imagining: “The Woman Upstairs is like that,” she says, “We keep it together. You don’t make a mess and you don’t make mistakes and you don’t call people at four in the morning.” Her resignation of this is not defeat, but a promise, a woman (women) lying in wait to get what is rightfully hers.

It is not simply the fact that Messud had the chutzpah to portray an unlikeable woman. It is the fact that she touched on the exact ways we shame and manipulate women out of feeling. How society demands they be The Woman Upstairs and then gaslights them whenever they have the audacity to be angry about it.

Messud touched on the exact ways we shame and manipulate women out of feeling.

I love Nora for the very fact that Messud cracks open her head and allows all that unlikability to bleed onto the page. I love Nora because she is angry and frustrated and fed up with the world. I love Nora because she has a chip on her shoulder.

I love Nora because I feel the exact same way.

We need so many more Noras, so many more female heroes that breathe fire and anger at what the world has offered them.

We need so many more Amazing Amys from Gone Girl who break down societal expectations for women with venomous “cool-girl” monologues, who go after what they want not with grit and pluck like the pint-sized feminists the world seems to love (Fearless Girl on Wall Street, Eleven from “Stranger Things”) but underhandedly, who succeed not with sticktoitiveness but instead with sneakiness and deceit. The kind of girl who plans to ensure success meticulous, as cold and callous and calculating as any whack on The Sopranos. “Cool Girls never get angry,” she tells us, “they only smile in a chagrined, loving manner and let their men do whatever they want.”

Amy is not a cool girl, she promises. She’s an angry woman, depressed over the unfair curve balls life has thrown her — fired from her job in a dying industry, forced to move to the middle of nowhere for her family, parents who use her, a husband who puts his own depression on a pedestal yet labels hers hysterical. She won’t hide that anger to make you comfortable; she will use it to get what she knows she needs.

We need so many more Mathilde Satterwhites from Lauren Groff’s Fates and Furies, a self-sacrificing wife in her husband’s version of their marriage, cunning and furious in her own version. A woman who doesn’t retreat into her depression, but uses it as fuel for her purposeful fire. Mathilde has been abandoned by her family after she causes a tragic accident, she is hated by her in-laws who believe she is only in her marriage for the money, her star is dwarfed by the success of her husband (“Somehow, despite her politics and smarts, she had become a wife, and wives, as we all know, are invisible. The midnight elves of marriage. The house in the country, the apartment in the city, the taxes, the dog, all were her concern: he had no idea what she did with her time,” Groff so perfectly encapsulates the unpaid emotional labor of wives).

Any of these would be enough to lead a character, a person, into depression, but Mathilde refuses to be paralyzed as Esther, swallow her emotions like Clarissa, be subjected to the gaze of the men in her life like the Lisbon sisters. Mathilde will fight, use anger to craft cunning and shrewd plans, use a cool calculated rage to achieve her desires. She will not be sidelined; she will speak her own story.

We need so many more. I’m part of a generation of young women who are told everyday that they are selfish, that no one owes them anything,that they have to pull themselves up by their own bootstraps. We are told to lean in but are slapped back by a culture that demands gratefulness. We are told to go after what we want, but are laughed at when we display annoyance or frustration when no one will even give us a chance to get it. We need women who push back against this narrative. We need women who show their rage.

We are told to lean in but are slapped back by a culture that demands gratefulness. We are told to go after what we want, but are laughed at when we display annoyance.

When I was a teacher, I used to tell my students that their personal narratives needed a lesson, a moral, something for the reader to walk away with. And I wish there was a convenient, internet think piece-style ending for this essay. Something tailor-made for a headline like “Finding Angry Female Heroes Helped Cure My Depression.” But, of course, that’s not the case, because depression is long and varied, with peaks and valleys that come and recede like unpredictable waves. It ebbs; I move forward, find ways to manage it, life gets easier.

But discovering these angry female heroes helps in the most basic of ways. They represent me. They show there is camaraderie in the way I feel. They make me feel justified and rightful for these thoughts that others dismiss as self-pitying or self-indulgent or overly pessimistic.

They represent me, a version of myself I’ve never had the ability to experience before in literature. They give me what everyone wants in the world, the ability to not feel so alone.