Lit Mags

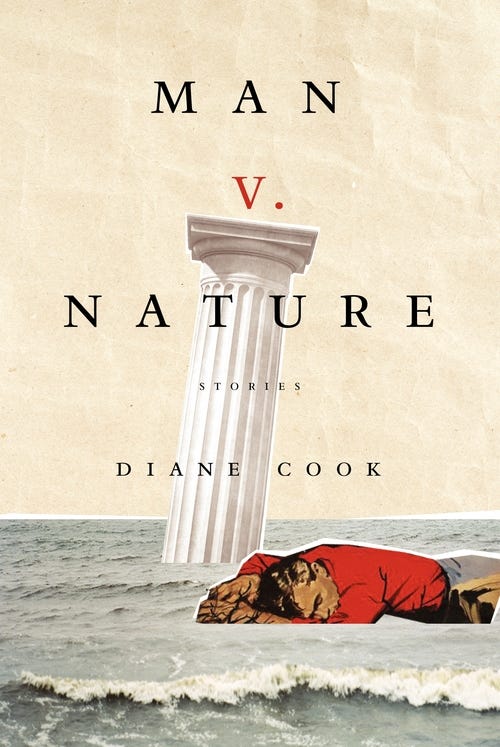

“Man V. Nature” by Diane Cook

A story about men with no solidarity

EDITOR’S NOTE BY TERRY KARTEN

I fell in love at first read with Diane Cook’s debut story collection, Man V. Nature. The distinctive vision that informs the book was fresh and unlike anything I’d seen. How exciting to discover an original and unexpected take on human nature and the world! Isn’t this what an editor of fiction is always hoping to find? The halls of the Harper imprint at HarperCollins Publishers were ringing that day as I trumpeted the good news to my colleagues. And now I’d like to present to you the piece that gives this book its title, in the hopes that you’ll love it as much as I do.

The title story in the book explores the mysteries of friendship, the surprises that lurk beneath the unexamined surface, and the chasm between what the narrator wants and the truths he uncovers, one by one, in spite of himself. This is a story of survival. It has a strange and eerie quality, especially as what should be a normal situation is transformed slowly into menace. How could this happen to three old friends, now middle aged, off on a weekend fishing trip on a lake? Lakes have boundaries, right? It should be impossible to get lost, stranded, but this is what happens. The real surprise is that human boundaries crack, too, and unleash a different kind of menace from the depths of human nature itself. The drama — surprising and unexpectedly humorous at moments but ultimately poignant and heartbreaking — plays out against the canvas of the elemental world.

The title story in the book explores the mysteries of friendship, the surprises that lurk beneath the unexamined surface, and the chasm between what the narrator wants and the truths he uncovers, one by one, in spite of himself. This is a story of survival. It has a strange and eerie quality, especially as what should be a normal situation is transformed slowly into menace. How could this happen to three old friends, now middle aged, off on a weekend fishing trip on a lake? Lakes have boundaries, right? It should be impossible to get lost, stranded, but this is what happens. The real surprise is that human boundaries crack, too, and unleash a different kind of menace from the depths of human nature itself. The drama — surprising and unexpectedly humorous at moments but ultimately poignant and heartbreaking — plays out against the canvas of the elemental world.

Here is a story worthy of such modern masters of the genre as George Saunders and Jess Walters. Read it, and then search out the collection to read more of the audacious and tragically human stories told by this unusual new voice in American fiction, the fearless, talented Diane Cook.

– Terry Karten

Executive Editor, HarperCollins Publishers

“Man V. Nature” by Diane Cook

Diane Cook

Share article

by Diane Cook, recommended by HarperCollins Publishers

It had been days since Phil and his two oldest friends drunkenly fished from the middle of the great lake for fat trout, the sweet orange flesh of which tasted best grilled over charcoal, under stars tossed absurdly across the sky like birdseed.

Days since Phil’s boat ran out of gas, stranding him and his friends during this, their annual fishing trip.

Days since Phil had seen another boat or passing tanker, which was strange on a lake usually choked by commercial traffic and sport boats.

Days since they’d placed bets on a timetable for rescue, and grown bored of spitting contests, of swapping sex stories, of imaginary card games.

Days since they’d devoured the beer brats and the buns. The coal-cooked sweet potatoes. The breakfast eggs. The butter for frying. The three bloody steaks they’d brought for the last night, when they figured they’d be tired of fish. All the A-1.

Days since Dan claimed the water was safe to drink, even though they were shitting and pissing into it, saying, “It dilutes,” as he swished a turd away.

Days since Ross, standing at the prow like a hood ornament, shielded his eyes against the bronze water of sunrise and insisted he saw land through a retreating fog, while their large pleasure craft heaved, weighty and useless on the swells.

Looking back, it’s clear they’d been fevered by exposure, buoyed by assumptions, not to mention drunk, when they decided to abandon said thirty-foot pleasure craft — the one thing Phil had held on to in the divorce, with its comfortable sleeping cabin and mini-fridge still stocked with two dozen beers — to jump into the cramped rubber lifeboat. They’d cheered, certain they could navigate it to a shore Ross insisted was there. “We’ll be walking on the beach in an hour. I just know it,” he’d said. They’d sat straight-backed and high-kneed like kings on tricycles; they rowed like ecstatics.

But that was days ago.

Ross and Dan, tired out from rowing nowhere, rubbed their tender shoulders and watched Phil with what he thought was skepticism, but hoped was appreciation, after he swore he could row them to land by himself, No problem, with the two child-sized oars — cast-offs from a summer camp and covered in green chipped paint.

“I’ve got this,” Phil said reassuringly. “I’ve been in worse shit.” He’d been an army man, after all. Ross and Dan exchanged a look. What did the look mean? Phil felt nervous. It was a risk to take charge. He used to like risk. But lately he’d grown wary of it.

Was the boat moving? With no landmark, Phil couldn’t say. He strained harder.

“Remember how I was the star of our high school team?” Phil reminded, hoping to bolster their faith in him, with his quivering shoulders and hands wet with panic.

Ross said, “Of track.”

Dan scoffed, “And field.” Phil was tall and skinny, had an abnormally long stride but not much strength.

Ross and Dan laughed. It was the first genuine laugh Phil had heard since they’d been relaxing in their real boat. The only sounds since had been waves slapping the rubber lifeboat, an occasional bird whining past. They conversed softly, as if to use their regular voices would be too jarring in such small quarters. “Can you pass some jerky?” in a whisper. The response, not necessarily unkind. “No. You had your piece today.”

Ross and Dan’s laugh sounded like a new thing, so Phil joined in. It felt good to laugh.

“Dan the man,” he said with affection. He clamped his hand on Dan’s shoulder. It felt so normal; even Dan’s bristling at his touch.

Ross and Dan hunkered into an exhausted sleep while Phil tried to row his friends to shore.

In the night rains came, and the men groggily scooped water from around their feet until it began to merely drizzle and they drooped back into an unhappy sleep.

When morning came, Phil held only one oar.

Had he fallen asleep? the two men asked Phil. Yes, yes, he had, he answered. Hadn’t he tied the oars to his wrists so he wouldn’t drop them while he slept? Like they’d all agreed they would? they cried. No, he answered calmly, no, he hadn’t.

Phil cleared his throat. “This is not a problem,” he said. Phil would row with the one oar into the currents that moved like ribbons through the water. The currents would help push them closer to the shore. Gray lake and sky blended into a perfectly blank dome. If someone told them they were upside down, Phil thought, he would not be surprised. When Dan and Ross chewed their lips and exchanged more looks, Phil decided, they are putting their faith in me.

The boat dragged in circles. And when the weather broke and blue sky emerged, the men discovered that the land Ross swore he’d seen — that Dan and Phil believed he’d seen — was gone; the horizon lay sharp in all directions. If something had been seen, Phil guessed it had been clouds, a bank of them hugging the water like a real distant shore would.

Ross pawed at his face and sobbed, “My girls,” for his wife, Bren, and their three daughters, who were sure to have called the police by now, who’d no doubt sent search parties, search boats, search planes. Which made it even more frustrating that the men were still lost, drifting, alone. Phil looked at Ross’s sunburned, bald head, handed over his own hat, and said gently, “Hey, boss, you’re blistering.”

Each morning they rotated positions, two on the plastic bench in back and one on the rubber bottom at the bow. The two on the bench bumped elbows, smelled the other all day, shifted ass cheeks to avoid sores. Whoever sat on the bottom could stretch his legs and lean against the side. They coveted the spot for sleeping. Early on, Phil had hoped the other men would offer the spot to him indefinitely; he was the tallest, which made folding himself onto the plastic bench that much harder. Plus, it was his boat. But the other men decided to share. It was more fair. In return for getting the spot for the day, the man on the bottom had to massage cramps out of the other men’s calves and feet.

Phil was stretched out, locking and unlocking his knees. Quietly, he kneaded the blood back into Ross’s bloated legs while Ross groaned in good pain. Dan twirled his mustache and stared into nothing, patiently awaiting his turn. Though they weren’t on the ocean, all around them Phil smelled salted air. It must be coming from us, he thought, and licked his own shoulder. He tasted like a warm olive. His mouth watered precious spit.

The thirty-foot pleasure craft was long gone. After that first day of rowing, they could still see it as night fell, bobbing on the horizon like a fishing lure. But in the morning the sun lit flat, empty water, with no pleasure craft in sight. That was a hard morning for Phil. The men asked him to use the GPS to find out where they were. And Phil had to admit that it was still on the boat they’d abandoned; he’d forgotten to grab it, he’d said.

The truth was Phil had remembered it but couldn’t unhook it from the control panel, and really had never learned how to use it anyway. He only took the boat out this one week a year. It had sat in a marina weathering while he was living out west. He wasn’t even sure why he’d fought Patricia so hard for it. Maybe because she had wanted it, which was ridiculous after she had given him so much grief for buying it in the first place. “Get a job you like,” she’d barked. “Then you won’t have to fill your empty life with meaningless crap like that stupid boat.” He cried when he saw the boat in the list of assets she demanded. Now she had the house, the nicer car, the dog, which she gave away to an old friend. The friend had called Phil to offer the dog back, saying it felt weird, owning Phil’s dog. But Phil didn’t know how to go about retrieving the dog. He’d gone east, and the dog was west. He didn’t want to fly to get the dog and be in the same city as Patricia — there was the issue of that court order. But he didn’t know how to ship a dog. Would he have to call an airline to schedule it? UPS? The thought of making phone calls overwhelmed him. So the friend kept the dog.

“He’s asleep,” Dan garbled, and nudged Phil’s hands onto his own leg. “My turn.”

The three men had been babies together in the same neighborhood; their moms took turns watching them, shuttling them from house to house without ever having to cross a busy street. Still, Dan and Ross had always been the better friends; they were true next-door neighbors, while Phil lived down the street. They flashed Morse-code messages through their bedroom windows when they should have been sleeping. But Phil was too far away to join. Ross and Dan went to the local university, Phil to the army. But they all stayed friends, Phil made sure. Dan was a television writer in the city, a serial dater, the best man at their weddings. Ross lived in their hometown, had the family, golfed at the municipal golf course. Phil atrophied at a base out west, met and married Patricia there, then stayed to be with her. What a mistake. That kept him out of the loop. He should have tried to come back home. Dan’s parents still lived in town, and Phil knew Dan visited often. Ross and Dan must have seen each other then, but they never talked about it.

One time, a couple days into their lifeboat drift, Phil had jumped into the water to cool off after assurances from Dan and Ross that they would help him back in. A few yards from the lifeboat, he turned to watch them. He saw how the men stretched out luxuriously, how Ross clasped his hands behind his head and sighed, and how Dan did the same. The men smiled and laughed about something, enjoying themselves, almost. Phil never left the boat again.

Days passed. The men hadn’t spoken in at least two. Or was it more? How many more days? Phil wondered. As another night fell, his mind droned. He hated being alone with it.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “Let’s play a game.”

“Like playing imaginary cards?” Dan scoffed.

“Sure,” Phil said gamely. “That might be good.”

“I was joking,” Dan said.

“Okay.” Phil tried again. “We could bet on if we’ll get rescued.”

Ross scowled. “You’re a macabre fuck.”

Phil fake chuckled. “You’re right. How stupid of me. That’s not a game.” He stroked his chin. “What about girls? We haven’t talked about them in a while. That can’t be bad, can it?”

The other men shrugged.

“Ross, why don’t you start,” Phil encouraged.

“Fine.”

Phil closed his eyes. He was just beginning to stiffen when Ross stopped talking and yawned pointedly.

“This is boring,” he said. “Also, I’m tired.” His blisters had turned to wet sores, and he winced every time the wind stroked his oozing bald head. His energy bled out of it.

“You’re always tired,” Phil said. “Keep talking.” Even with his eyes closed, Phil could tell looks were exchanged — the boat shifted slightly as the men turned their heads.

In the distance, geese landed in a mess of honks and splashes. Ross remained quiet.

“Maybe just start from later in college,” Phil said. He wanted to hear about Bren. Beautiful blond Bren.

Ross trudged through the story of the flexible roller skater and her bleached pubic hair, his voice flat and uninterested.

Phil waited.

“Then I met Bren,” Ross said, and he choked on her name, sounding angry almost, which in a strange way made it a new story to Phil. Like a new encounter. A new first time. Nothing boring about that, Phil thought, his body warming.

There it was.

Ross sobbed into his clenched fist, unable to continue. But it was enough. Phil carefully slid his hand under his waistband, skimming the raw chafed skin around his middle, and tried to let the images and a light touch do the work so the boat wouldn’t quiver. Sweet Bren wearing only cotton panties, giggling into her hand. He’d meant only to comfort himself, not climax, but he was the hardest thing for miles. Inside, everything lined up.

“We know what you’re doing, Phil,” Dan said, disgusted.

“Shut up,” Phil hissed. Distracted, a banal dribble slipped out. But that was all. No big release. Frustrated tears sprang. “I hate you,” he muttered. It sounded like a yell.

Phil hid behind his closed eyes. When he opened them, he saw that Dan was asleep, his head loose and lolling with the swells. But Ross sat rigid, arms crossed, his gaze seemingly fixed on Phil. In the shadows made from slivered moonlight, Phil couldn’t tell if Ross’s eyes were shut or if his stare was meant to accuse Phil of something. He held his breath. Soon, he heard Ross snore.

Even though Phil had the floor, he couldn’t sleep. His inner drone continued. As night passed he watched the stars blur and the eerie green auroras appear, spilling along the horizon like paint. As his sight adjusted, the night was not as pitch-black as before. It shone through his eyelids like the glare from a streetlamp.

He picked at his crusty shorts. He filtered through questions to soothe himself to sleep. Why hadn’t they been rescued? Where were the other boats? Was it the end of the world? What did Ross really think of him? Who did Dan like better? Every question he asked yielded an unsatisfying answer that woke him more. To make himself feel better, he ate the last of the peanuts. Then he leaned toward Dan, felt Dan’s rotten sleep breath in his face, and cleanly plucked the last strip of jerky from his pocket.

Phil woke to the wind in his hair and Ross and Dan bellowing, “One, two, one, two!” They synchronized feeble hand scoops through the water like a crew team, but they went nowhere. They spun in slow circles.

Ross and Dan spat words and dusty saliva toward Phil. They’d woken disoriented, frenzied, lost to time.

“The jerky is gone!” Ross barked.

“The peanuts!” Dan screamed. He took a breath and screamed again.

The remaining oar was also gone.

“How?” Phil asked.

Ross and Dan stopped mid scoop.

“Someone must have taken it,” Dan said, and scratched his palms, pilling bits of grime and skin. He looked over his shoulder as if someone had tapped it.

“Who could have done that?” Phil asked. He focused on seeming innocent.

Ross eyed him.

There was no good answer to this question, and so they settled into an uneasy calm.

Phil felt roller-coaster queasy; the final part, when the hills come too quickly.

We are unlucky, he thought. Like people who always miss the bus, even with a schedule. Though maybe luck is cyclical. Maybe luck was constantly on the move, gracing people and then leaving them. People with luck or good fortune early in life — they’ll crash into a snowbank and freeze to death, slowly over days, to the sound of other cars passing just out of sight, or get snarled in the propeller of a boat when they’re snorkeling on a relaxing vacation, or die giving birth to their child. Phil tried to think of when luck had visited him last, if ever. Was he due for some, or had he squandered his share long ago?

Phil peered sheepishly at Ross from under his lashes. “I slept with your wife.”

“I know.” Ross dunked his head in the lake.

Dan clapped his hands gleefully, and the resulting pop was the morning’s only other noise. “If I were a television writer, I’d be writing all this down, because this is gold.”

“Dan, you are a television writer,” Phil said. He laughed, but the lake dampened the sound and it came off morose.

Dan scowled. “That’s what I meant. I meant if I had a pen.” He picked at a sun blister on his thigh until he let loose the pus. He dabbed his finger and licked it.

“Did you sleep with my wife?” Ross asked, easing a leg out for a stretch. It brushed by Phil’s shoulder, purposefully, Phil thought.

Ross dunked his hands into the lake and gave each underarm a good scrub. He smelled them with fascination.

“Does it matter?” Phil asked. He’d hoped what he said would come off as a joke, and was annoyed it hadn’t.

“Yeah. Yeah, I think it actually does, now that you mention it.” Ross flicked his wet hands in Phil’s face. “Now that we’re here, I think it matters.”

“Well, then, no, I didn’t.”

“Why did you say you did?”

“Because I wanted to. I’ve always wanted to sleep with your wife. She was hot.”

Dan nodded. “She is hot.”

Ross shrugged and twirled the minute hand around and around on his watch.

Phil scratched his head. “Why did you say ‘I know’ when I said I slept with her, if I never slept with her?” He was beginning to suspect Bren had said something to Ross. It was years ago, and they’d been so drunk, and it was only a blow job.

“Because I thought you did. I always thought you did.”

“How could you think that? How could you think I’d do that to you?”

“Because I banged your sister. Remember?”

“Why would you bring that up? When we get home I am going to sleep with Bren. You deserve it.” Phil stared out at the water. The way it moved on its own made him feel vaguely wet, like he was becoming part of the lake, being absorbed.

Ross chuckled. “No chance,” he said, not even bothering to look at Phil. Which stung. Did he mean they had no chance of making it home, Phil wondered, or that he had no chance with Bren? How could Ross seem so sure? Had Bren said something? Phil squirmed in the bottom of the boat, trying to quell his burgeoning erection. He wanted to sleep with Bren badly.

“If I were writing this into a television sitcom,” Dan mused, “or even a movie, I would have written this as a fight scene. Every time you guys say something, I’d have you start wrestling, so that the boat is almost tipping, and things get very tense for the audience, which thinks the boat is going to tip, but then I, or, you know, the actor playing me, intervenes and says something like — ” Dan put his finger to his lips, thinking, then hollered, “ ‘Hey fellas, something something blah blah,’ and then cue laugh track” — he pointed to the wavy gray horizon — “and that would calm you down because, you know, metaphors, etc. And then some action music would play, and we’d start figuring a way out of this mess.”

Phil looked at Ross. He wiggled his eyebrows in a way that asked, Is he losing it? But Ross wouldn’t look at him.

Ross, instead, looked at Dan with interest. “What is the way out of this mess?”

Dan scratched at the rubber seams beneath him. “I’m glad you finally asked. Let’s flag down one of the tankers we keep seeing.”

“We haven’t seen any tankers,” Phil said.

Dan’s face registered shock, but then a vague smile appeared.

Ross glared at Phil.

“All right, then,” Ross said soothingly to Dan, “we’re three men in a boat in a large lake that is a major shipping route. Why have no boats passed to rescue us? I want you to write me a world in which that happens. I want my own television show, dammit.”

So Dan told them about how, the other day, a coup d’état occurred in Canada. Rebels blocked all waterways and ports in protest, and were holding the prime minister hostage. Armed gunmen had broken into his room late at night while he enjoyed a cigar and a brandy, though this particular boutique hotel had strict no-smoking rules, which would be communicated by a slow pan from a No Smoking sign to the prime minister relishing a thick exhale just before the armed men barged in, threw a bag over his head, and dragged him through the hallway to the service elevator. Patrons screamed and cowered against walls at the sight of the guns because Canadians are peaceful nancies. The armed men brought the prime minister to the basement, which was really a dungeon from colonial times. They tied him to a chair and threatened to rape his daughters if he didn’t cooperate. They’re twins. “Double the pleasure,” one of the more dastardly gunmen said, twirling his waxed mustache. The prime minister broke under the pressure of picturing his beautiful brunette daughters brutally raped, shown in slow, soft-lit vignettes so that it’s classy and, of course, feminist. Viewers would be horrified and so would understand — would have sympathy for — the prime minister when he handed over the country to these armed men.

Dan paused, finger to lips again, and again looked over his shoulder at an imagined encroaching someone or something. He continued in a whisper. “Okay, listen, the army steps in, overthrows the prime minister, strips him of the authority to give the country to the gunmen, and proceeds to fight the rebel forces. So there are no boats here right now because in the seaway that leads to the ocean, the one we’re heading for, a fantastic battle is taking place. Picture it: Underwater torpedoes! Cannons! They’re fired from the bluffs by scrappy yet handsome, thrown-together village armies. Your run-of-the-mill believe-in-able poor-people types. The kind that wear potato-sack clothes and such. Somehow a pod of government-trained beluga whales is unleashed to deliver explosives — strapped to their heads on helmets, okay — by swimming under enemy boats and blowing up themselves and the boats. Total kamikaze shit. We’re talking whale medal of honor.” Dan punched the air. “The war is on. Boom. Prime time.”

“That’s quite a show,” Ross said. “What are you going to call it?”

Dan snapped his fingers. “Man V. Nature.”

Phil laughed. The other two looked at him. He’d thought it was a joke. “Why?” he asked.

“Everything is man versus this and man versus that. It’s so simple,” Dan said, his voice rising. “It’s man versus everything. It’s me. It’s you. It’s us. It’s in us. It’s in — ”

“Okay, okay, but it’s a war story,” Phil interrupted. “It should be Man Versus Man.”

“I’m the writer. I get to call it whatever I want. And it’s Man V. Nature.” Dan crossed his arms, satisfied. He had made his point.

“Well, I’m calling it Man Versus Man. Try and stop me,” Phil said. He meant it jovially, but joviality seemed to be dead, at least where he was concerned.

“I’d watch Man V. Nature,” Ross said to Dan. His point was not lost on Phil.

“Oh, I would too,” Phil chimed in so he’d feel included. He itched a spot on his ankle that he’d already scratched raw. Under his fingernails he smelled rot.

Dan slammed his fist down on the hot rubber side. “God, I wish I had a pen. Some paper, too.” Then a look like happiness passed over his face. “When we’re rescued, I’m going to sell that show and make you a star.”

“Me?” Phil asked.

“No, not you.”

Ross smirked. “You’re the star of Man Versus Man, remember?”

A flock of geese flew by their boat, their shit making splashes like tiny bombs in the water.

A kind of bare grief Phil saw in movies but rarely experienced himself bubbled up. He was not quick to trust it. He said, “Cool.”

Phil dipped his beer can into the lake and splashed it around to part the sun-warmed surface water so the icy stuff below could rise up. He let the can fill and drank it in one long gulp. “Why would I sleep with your wife? I had my own wife.”

Dan and Ross chuckled and exchanged an incredulous look.

“Because your wife sucked, and my wife is awesome,” Ross explained.

“Patricia didn’t suck.”

“Um, yes, she did. She sucked. And you hated her.”

“No, I didn’t. She hated me. But I loved her. I really did. That’s the truth.” He didn’t know if that was the truth. Honestly, he probably hadn’t love her specifically, but he’d loved that she was a woman, acted like a woman, and had at one point, early on, seemed to love him. Or pretended to. But it didn’t matter now. He hated her now.

Phil poured a can of water on his head. He filled it, did it again, and then again until Dan whined about water in the boat. Phil stumbled to kneel, pulled out his penis, and tried to aim over the side like they’d always done, but the stream was weak and urine pooled in the lifeboat. Instead of yelling, Ross and Dan shared a look, and again Phil was at a loss for what it meant.

Dan pulled out a strip of jerky from a secret stash in his shorts. He passed it to Ross, who held it up like evidence. It wilted in the heat. To Phil, it smelled like real meat cooking on a grill. Drool spilled down his chin.

“This is the last one,” Ross said to Phil knowingly, and pushed the length of it into his mouth.

Dan woke screaming “Fire!” and jumped up from the sagging plastic bench. His shorts were wet, and a deep intestinal smell wafted from him. Ross yanked down Dan’s shorts to reveal an oozing patch of holey flesh covering one entire cheek. The smell forced a puke from Phil. Ross soaked his T-shirt in lake water and gingerly pressed it to Dan’s ass to clean it. Dan stood naked like a toddler in the backyard sun. A smile played at his lips as he surveyed the lake reaching in all directions. He turned to Phil, who was rinsing out his mouth. The boat shook, shivered.

“Does it look like it hurts?” he asked.

“It looks like it will kill you,” Phil said.

Dan giggled. “It doesn’t hurt one bit,” He repeated it under his breath, emphasizing each word, until the men helped him lie on his side along the bottom of the boat. There would be no more rotation of seats. Phil and Ross settled next to each other for the foreseeable future.

Phil slept poorly, fighting off annoyed elbow jabs from Ross. Phil wanted his sleep time to be an escape. He wanted to dream of a girl, of Bren. But what if he called out her name and Ross heard? What about dreams of some vacation, some cabin in snowy woods, instead? A fireplace. Some beer. Or maybe he could dream of flying. Away. From here. In the end, he dreamed of birds, their talons puncturing his arms as they pried white worms from the blisters on his neck.

“Wake up,” Dan hissed, slapping their thighs and feet, whatever was closest. He was frantic again. “Get your things together. We’ve got to go!”

Ross rubbed his eyes. “Where? Go where?”

Phil tried to get his bearings. He looked around. He touched his neck.

“Down there,” Dan shrieked. He pointed into the water. “Listen, I’ve been hearing more about this war that broke out, you know, I told you about it.” They nodded, bewildered. “Well, it’s getting worse. Common citizens are taking up arms to push the rebels out, and it’s full-on revolution all around us. You can hear it if you listen really hard.” Dan squeezed his eyes in concentration. Phil heard a trickle of water, and saw Dan pee himself.

“It’s a humanitarian nightmare. World War Three. The only safe place is under the surface. I mean, think about it.” His eyes bulged. “It’s kind of beautiful. This world collapses. But the world below this world — it flourishes. Man V. Nature. See?”

Dan propped his chin on the side of the boat and peered into the water. He marveled, “We are actually in the perfect position. Stuck out here, we are citizens of no world. And so we’re totally welcome down there.” Dan gazed at Phil with admiration. “I don’t think I could have done it. But you have guts. You knew something was happening. You kept us out here. You’re kind of a genius, man. I’m so dumb, I thought we were going to die. And soon.” Dan laughed hard. “Turns out we’re gonna live.” He briefly air-guitared.

Phil blinked. Was he serious? “I didn’t keep us here. I didn’t know anything,” he said.

Dan’s chest heaved. He sweated. “Bren and the girls are already down there. Say hi, Ross,” he said, waving at the water.

Ross’s mouth gaped, but despite himself, he looked. “I don’t see anything.”

Dan clutched at his own shirt. “You’re a terrible husband. Terrible father. You just broke their hearts. Right in two. Don’t you see?” He twirled his finger in the water, creating ripples that moved farther away from him. He leaned out, peering closely at the center spiral he’d created.

Ross said, “Hey, pal, get yourself back into this boat.”

Dan turned to Phil. “Don’t you see?” he pleaded.

Phil shook his head.

Ross said again, “Get in here. You can’t leave me. If you leave, I’ll die of boredom.”

Phil winced.

Dan choked out a real sob. “But I’m so tired, Ross.” He said it like a secret he didn’t want Phil to know.

Everything was still, and Phil thought maybe the moment had passed. Then quickly, easily, Dan slid his body over the side of the lifeboat. Phil managed to grab his foot, but his shoe came off with a couple of kicks, and they watched Dan waggle and pull, like a kid diving for toys in a backyard pool, until the darkest water swallowed him.

“I’ve got to go in, get him,” Ross said.

“We’ve got to get him,” Phil corrected.

Neither man moved.

Air bubbles rose to the top for a few minutes and then the lake was calm.

“Fuck,” Phil said, holding Dan’s shoe in the air. Ross snatched it and threw it overhand, the force pitching the boat wildly. It plunked like a stone into the water. The ripples went on forever.

Phil thought Ross would make a play for the better seat, now that Dan was gone, but instead Ross slumped over, barely propped up by his own bones. Phil slid to the boat floor and stretched out. He stifled a groan of pleasure out of respect for Dan.

Ross didn’t say anything all day. He just peered over the edge like he was looking for something important and kept almost seeing it.

When the sun began to set, Ross reached into a zippered pocket on the inside of his shorts.

“What’s in there?” Phil craned his neck to see. Maybe it was food.

“It’s nothing,” Ross said, taking out an index card and a stubby pencil, the kind used at golf courses.

“You had paper and pencil this whole time? And you didn’t give it to Dan?”

Ross waved the card in the air. “Too small to fit a whole TV show on, don’t you think? Besides, I didn’t remember I had it. What kind of asshole do you think I am? I would never do that to him.” He bent over the card.

“What are you writing?”

“Nothing that concerns you. It’s for my girls.”

“Are you going to signal a bird to pick it up and fly it to them?”

Ross singsonged, “Meh. Meh. Meh. Meh. Meh,” mocking Phil’s comment, his voice. He scooped water from the side of the lifeboat and flung it at Phil. Phil retaliated by filling his cupped hands and dousing Ross’s lap and scorecard.

Ross leaped to his feet and the boat bottom folded, water rushing over the side. A cramp from sitting so long seized him and he lurched forward, bending deeply, so his face met Phil’s. His sunburned eyeballs looked like the bottom of a dried lake bed. Tears burst from them and tracked through the grime on his face. “You expect me to believe you didn’t do this on purpose?”

“Sit down! What are you talking about?”

“Strand us out here. You know, run out of gas.”

Phil laughed. “Calm down.”

“You just happened to forget to fill the tank? That’s crap. We’ve been coming out here how many years?” Ross sat down with a thud, and more water poured in.

“That’s baloney. You’re crazy.” True, Phil hadn’t filled the tank up all the way. Dan and Ross hadn’t offered him any money. It was weird. They usually did, but this time they’d just pretended to look at the map when he backed the boat trailer up to the pump. Gas was so expensive now. He’d felt uneasy ever since he’d picked up Ross. He and Dan, they’d been fine, talked about girls Dan could fix him up with now that he was single. But then Ross had gotten in the car. Phil thought then that maybe Bren had finally told Ross about the blow job. He’d always thought Ross acted weird around him, ever since. For years he’d assumed Ross knew. He wanted Ross to know, to know and to go on these trips with Phil anyway. Because they were such good friends and nothing could ruin that. And Phil could feel he’d gotten away with it. And then maybe it could happen again, with Bren. It had been a fantastic blow job. He’d been drunk, yes, but he still remembered it. She acted drunk, but he knew she wasn’t. She had wanted to do it. And the fact that Bren never came to the door to see Ross off on these trips was proof to Phil. She was harboring some serious feelings for him. God, Bren. They used to have a ball together back in the day. They’d all go out when Phil visited for the holidays, him and Dan and Ross and Bren. Ross and Dan always drank too much and were a mess. But in basic training Phil learned how to act sober even when he wasn’t, so he always offered to drive Bren home and then would rejoin Ross and Dan later. They never suspected anything. Bren was so giggly and her mouth was so big, with her sleek white teeth and that thin slippery tongue. They made out the first couple of visits, and he felt her up frantically. And when she was pregnant, her tits were unreal. And then, that fantastic blow job. But then she stopped going out with them when he was visiting. “She’s with the kids,” Ross would explain. And Phil always thought he saw a weird look on Ross’s face.

“We weren’t even going to come this year. Me and Dan,” Ross said. “We talked. Yeah, we talked about stopping with this stupid week. We hate it. And Bren hates it when I go. Not because I leave her, but because of you. She says you’re a creep. And she makes this face when she says it.” Ross pruned his. “Me and Dan have our own week. In June. We go rock climbing. It’s awesome. And we were planning even more weeks. Dan was seeing a girl. We were going to have them to the cabin. She’s great. I bet you didn’t even know about her. I bet you never even asked what was new with Dan. Like, ‘Hey Dan, what’s new with you?’ ” Ross looked like he might spit at Phil, head-butt him, but instead his face drooped pitifully. “But then you got divorced, and god, you were so fucked up. We felt bad because we’re nice people. So we came, and now look. Dan is living with mermaids and it’s World War Three, and we’re never going to get out of this shitty, shitty rubber boat.” He hung his head. “My girls.” He wept.

Phil slumped against the hot, squeaky wall. He couldn’t believe it. They felt sorry for him? Was that why they didn’t give him any gas money? Because they didn’t really want to be here? And Bren said he’s a creep? He didn’t believe it for a second. Did they really go rock climbing? Did they really have their own week?

As boys, when Phil asked to sleep over, Ross and Dan had told him their moms had said no. He’d had no reason to doubt it was true. Phil had done everything to make sure they were friends. He gave them candy, money, comic books. When they got older, he let them drink his parent’s liquor and took the blame. He’d bribed his sister Maggie to have sex with Ross, who was still a virgin by the time he left for college. He didn’t know she was a virgin too, but Ross told him. Ross said Maggie was a crybaby. Then Ross went off to college and met Bren. And Phil went into the army, developed a gambling habit, had a series of failed relationships, pined for Bren, finally settled for Patricia, quit gambling, thought his life would turn around. It had. He believed it had. Until a year ago, he believed that. And even though Ross and Dan hadn’t wanted to come, in the end they came. That meant something, right?

“I’m sorry, boss. Please, I’ll do anything,” Phil said. He got goose bumps from the familiarity of wanting something he realized he couldn’t have.

Ross’s eyes were swollen and red, but hard. His mouth tightened into a smirk. “If you want to be my friend, you’ll never talk to me again.” He turned his head away and bent over his knees to sleep.

In the morning, Ross was gone. His water-warped golf scorecard was tucked into Phil’s clenched hand. On it was written: Got rescued! You looked so peaceful I decided not to wake you!

All around Phil was the same still, gray water that had surrounded their boat for days. Weeks? Months? No land peeked out from behind the morning fog. No wake from a passing ship spread itself into thin ripples. Did Ross really get rescued?

Phil groaned an alone kind of groan: deep and howling, a major pitch-shifter. How many more signs did he need? Adrift on a lake for countless days without another soul in sight? No search parties? Friends who got rescued and left him behind, or who’d rather drown than stay in a boat with him? He’d rather drown than stay in a boat with himself. Life was over. He was tired of life. Life sucked. I want to live, he thought. Really live. Let go of the world. Wasn’t there a way to get to the ocean from here? Everything is connected to an ocean somehow. Yeah, he could float up that seaway Dan mentioned, to the Arctic, where no lawyer could get to him. He could find a way to catch fish and just drift through icebergs and shower in whale spouts. Now, that was a life. Not like his. Divorced and forty. No kids. He should have taken that as a sign. She didn’t want to have kids. What woman doesn’t want to have kids? He kept waiting for her to say she wanted them. It’s the guy who’s supposed to not want kids; the wife is supposed to be like, “We’re having kids, you asshole,” until the guy feels pushed into it and resentful. But when they pop out he’s supposed to realize that his kids are the reason life makes sense, and then he’s supposed to love his wife even more, want to get a better job, discover his new life purpose as protector of his family. That’s how it’s supposed to go. Except she didn’t want kids. Didn’t even want to talk about it.

Phil wept. The crust around his eyes melted back to goo. He wept for all the kids he never had. He’d always wanted kids, ever since he was a kid. Since going fishing with his dad down at Pickerel Lake, standing on the shore, casting off. The silence. The stillness. The heat penetrating their baseball caps. Here comes his sister, fast, yelling down the path, and here’s his dad hushing her and then, seeing her little shamed face, picking her up and swinging her upside down over the water until she wails, then cradling her in his arms until she laughs. It made so much sense even back then. That’s what you do. You have a bunch of them and they’re your friends. They look like you. You give them your feelings. It’s animal. It’s basic. What kind of cunt doesn’t want kids? “Stretch marks,” she had said once, laughing it off. His whole life. Wasted.

Phil’s grief pulled him to the bottom of the lifeboat and he curled up. The water there, trapped and warm, pruned him.

The golf pencil wavered by his head. He plucked it and drew a stick figure on the other side of the scorecard, in a small corner that hadn’t already been written on and scratched over by Ross. He made out I love you but could read no more of Ross’s words.

From the figure, Phil drew a thought bubble. Hello, he wrote within its girlish borders.

At first the stick figure was Patricia, but he was silenced by the desire to say the perfect thing to either hurt her or to fix things. Then it was Ross, but he could only think of apologies, and for what, he couldn’t say. He missed his friend. Was the figure a child? He couldn’t see it; it was unfamiliar. A stick figure. It didn’t look like him at all. He stared at his companion mutely. Eventually the paper fell from his fingertips and disintegrated in the rank stew where he lay, fetal.

He roused himself in time for a puke over the side, and in the bile-soured water he saw his own reflection. Who will miss me? he asked himself. No one had. It was real, a fact. The proof — his solitude. He stared, seemed to wait days for the answer. He laid his head down, smelled the hot rubber.

At the next daybreak Phil took notice of, he lifted his head to a new smell. Pine. The morning fog rolled away like a stage curtain to reveal rocky cliffs, evergreened at the top, on either side of him, as the large lake funneled into an ever-narrowing channel. He saw the current quicken around his boat, swirling, tugging, caressing.

He thought of Canada. Of the war. Of beluga whales, their pinked heads breaking through the black surface to breathe, misting everything into a watercolor.

“Don’t shoot,” he yelled to all the hiding rebels. He held up his hands in mock horror, his voice echoing off the bluffs surrounding him, and it sounded as though the hills were full of men begging for the same mercy as he was. He doubled over and laughed until he wheezed like the aged.

The water flattened, and Phil saw the hull of a ship maneuver a bend, miles in the distance.

The current carried him toward the enormous vessel, a tanker of some sort. When finally next to it, he rapped his knuckles on the side. It was metal, and the rumble it threw back was like dungeon doors closing. Water had worn away the blue paint, which now only covered the higher-up walls. He sliced his palm against the large white barnacles stuck to the hull, and blood the color of cartoon apples flowed out.

A real boat.

Just then a rope ladder unfurled down the side, and Phil grabbed hold.