essays

MEDIA FRANKENSTEIN: Halloween Special

A Monstrous Primer: That horror is often perceived as a boys’ club, most fans of the genre would never deny. Horror fiction is home to more Misters than Misses, and those who are active are underexposed. H.P. Lovecraft, E.A. Poe, Stephen King, Clive Barker, Peter Straub and the gang are trotted out as horror’s vanguards, Edith Wharton, Ann Radcliffe and Yoko Ogawa affectionately claimed as dabblers. Not unduly long ago the gendering was not so subtle; Flannery O’Connor’s tales of “mystery and misery and horror” in the South were disparaged by critics as “ highly unladylike,” O’Connor herself for “[slamming] down direct sentence after direct sentence of growing outrage…” As much to say: a woman shouldn’t. The Bram Stoker Awards, selected and presented by the Horror Writer’s Association since 1988, go overwhelmingly to men (the Shirley Jackson Awards, “established for outstanding achievement in the literature of psychological suspense, horror, and the dark fantastic,” boasts a more diverse roster.) Such privileging extends to film. Among 26 horror auteurs who were chosen to helm an hour-long episode of Showtime’s 2005 anthology series Masters of Horror not one — not one! — was a female director. Ditto among the three bigwigs summarily crowned as the genre’s elite — Tobe Hooper, Wes Craven and John Carpenter, with nary a mention of Jennifer Lynch, Claire Denis or Mary Lambert. Editorial titan Ellen Datlow says it best in her prelude to Nightmare Magazine’s “Women Destroy Horror!” issue: “For almost fifty years, hundreds of stories by women in the early years of horror, and their authors, were mostly forgotten. “

In dual honor of Halloween and #ReadWomen2014, Electric Literature’s “Media Frankenstein” column is hereby recommending 5 sublimely horrific media pairings to take with you into the week leading up to October 31st in ascending order off freakiness, all 10 (a combination of literature and film) directed or written by women. In the interest of keeping things listicle-like, the music limb has been lopped off.

1ST Creature

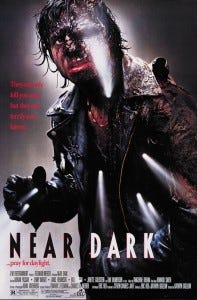

TOP HALF: Near Dark dir. Kathryn Bigelow (1987)

Near Dark is a Kathryn Bigelow film and it shows. Probably the only “hillbilly vampire road western” in existence, Bigelow’s movie is gorgeously shot, not least when it comes to the graphic bloodletting. From the death-by-spur scene in the honky-tonk bar to the hotel shootout with the cops, the action is the centerpiece, as twanging with tension and expertly staged as anything from Bigelow (Point Break, The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty). The plot is elegant and spare. Near Dark’s bloodthirsty undead — a nomadic family unit that calls to mind the members of an 80’s death-rock outfit (think Bauhaus or Christian Death) and that showcases performances from character-actor greats such as Lance Henricksen, Jenette Goldstein and Bill Paxton — roam the dust-blown highways and lonely truck stops of the rural Midwest, making snacks of mortal souls. They come upon Caleb (Adrian Pasdar), a farm-boy who falls in love with one of their minion (Jenny Wright) and whom they subsequently seek to induct into the gang, teaching him their vampire ways; although the word itself (“vampire”) remains unuttered start to finish, a subtle technique of Bigelow’s that estranges the story from bloodsucker tropes, making the mythos seem urgently scary. Yet the movie is more than just cold atmospherics; it also has a beating heart in the plight of the lovers (Wright and Pasdar), not to mention the plights of the other vampires except, maybe, for Paxton’s Severen, who he channels with shrill homicidal aplomb. The role is a companion piece to hysterical milquetoast Private Hudson, who Paxton played in Aliens two years before, a film that boasts Goldstein and Henriksen, too. (Bigelow and Cameron were married at the time, which people frustratingly like to bring up to explain why the former has gotten so famous).

If the supporting cast of Aliens isn’t enough to make you watch Near Dark right now, then look to the film’s grime-washed chiaroscuro, its aura of seedy roadhouses at night, its aimlessness and nihilism, and formal innovations sundry. Bigelow redefined vampire horror in the same way that Danny Boyle did it with zombies (28 Days Later) but nearly two decades before.

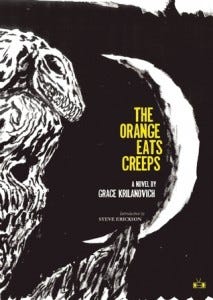

BOTTOM HALF: The Orange Eats Creeps by Grace Krilanovich (2010)

I’m not the first writer to reference Bigelow’s Near Dark and Grace Krilanovich’s debut novel The Orange Eats Creeps in the same grave-corrupted breath; critic Tobias Carroll used the crossover as a touching off-point in his 2010 review. Nor am I the first to be taken aback at the aggressive independence of the novel from the film, in spite of what strike me as purposeful nods. The Orange Eats Creeps bills its crusty-punk denizens of the Pacific Northwest as “hobo vampire junkies” hopped up on “crank, cough syrup and blood.” The novel itself reads like a freaky gene-splice of Charles Burns’ Black Hole and Lynda Barry’s Cruddy by way of 90’s hardcore zine culture, with a splash of Blake Butler and Poppy Z. Brite. Its nameless narrator, a vague teenage girl, describes her deathless cohort thus: “We’re blood-hungry teenagers; our rage knows no bounds and coagulates the pulse of our victims on contact… I can’t remember being a child, maybe I never was one. But I’m sure I’ll never die; I get older, my body stays the same. My spine breaks and then gets back together. I have the Hepatitis, I give it to everyone, but it never will actually get me. Our kind doesn’t die from anything, all we do is die all the time.” Just like in Bigelow’s film, the narrator and her band of “immoral shitheads” stalk the lonelier quadrants of the American West with nihilistic heedlessness, raiding drugstores, fornicating in public. Just like Near Dark, The Orange Eats Creeps revels in the flickering menace of quintessentially American roadside spaces after the circuits have gone on the fritz and normal folk are safe in bed. “Safeway at sunrise…” Krilanovich writes. “We storm through the doors… What would happen if you harnessed the sexual energy of hobo junkie teens?” Yet where Near Dark is about actual, if de-familiarized vampires, Krilanovich’s vampires are ambiguously realized; it isn’t altogether clear if they’re supernatural figures who live off of blood or if they’re just so whacked on drugs that their impressions of existence are de facto supernatural. In The Orange Eats Creeps there are no star-crossed lovers, just the reeking trash-scape of the self without end. What both of these bracing portrayals agree on: vampires are existential beings. They tell us as much about life beyond death as they do about life when the heart has stopped beating.

2nd Creature

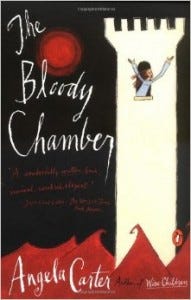

TOP HALF: The Bloody Chamber: And Other Stories by Angela Carter (1979)

Angela Carter has always struck me as one of the most criminally underrated horror writers — writers, period! — of the 20th century. That said if you have heard of Carter, it’s probably in connection with her story collection The Bloody Chamber, a company of fairy tale re-imaginings as feminist as they are phantasmal. And yet, when she wrote The Bloody Chamber, Carter never intended for her stories to be read as retellings. In Carter’s own words: “My intention was not to do ‘versions’ or, as the American edition of the book said, horribly, ‘adult’ fairy tales, but to extract the latent content from the traditional stories and to use it as the beginnings of new stories.” These phantasmagoric allegories, then, were baroque, and loaded up with sex and murder.Director Neil Jordan (Interview with the Vampire, Byzantium) adapted one of the stories from The Bloody Chamber (“The Company of Wolves”) starring Angela Lansbury and Stephen Rea in 1984; Carter co-wrote the screenplay. In that story, a re-imagining of the Little Red Riding Hood fable, the wolf — here a Huntsman turned werewolf and described by Carter in the overture as a “grey [member] of a congregation of nightmare” — kills the apron-clad, bible-toting Granny and lies in wait for Little Red. In the original story, Little Red Riding Hood gets eaten herself and must rely on the Huntsman to perform a life-saving autopsy on her devourer to save her and her Granny; in Carter, Little Red seduces the werewolf, engaging in “a savage marriage ceremony” with him to the howling of lupine familiars surrounding Granny’s cabin. The anti-myth is clear enough; Little Red has come into her sexual nature, by her own agency, not a moment too early. Carter’s gory re-appropriation of female sexuality as a supernatural force in The Bloody Chamber would go on to spawn other reinventions of popular myths and genres into the late 20th and early 21st centuries — for example, the excellent werewolf film Ginger Snaps (2000), written by Karen Walton, in which female puberty is likened to lycanthropy, and the immeasurably less excellent Twilight, in which Bela, a descendant of Carter’s Little Red, takes the feminist movement a century backwards. Without Angela Carter, we’d have no Brian Evenson, no Aimee Bender and no Kelly Link; we’d certainly have no Kate Bernheimer. Elsewhere in The Bloody Chamber, Beauty brings about a transfiguration in the Beast (“When her lips touched the meathook claws, they drew back into their pads…”), and Sleeping Beauty is refashioned as queen of the vampires, “the last bud of the poison tree that sprang from the loins of Vlad the Impaler who picnicked on corpses in the forests of Transylvania,” her Prince Charming a blithe young fool on R&R from WWI. In the latter (“The Lady of the House of Love”), Carter writes: “The Countess stood behind a low table… With her stark white face, her lovely death’s head surrounded by long dark hair that fell down straight as if it were soaking wet, she looked like a shipwrecked bride. Her huge dark eyes almost broke his heart with their waiflike, lost look; yet he was disturbed, almost repelled, by her extraordinarily fleshy mouth, a mouth with wide, full, prominent lips of a vibrant purplish-crimson, a morbid mouth. Even — but he put the thought away from him immediately — a whore’s mouth. She shivered all the time, a starveling chill, a malarial agitation of the bones. He thought she must be only sixteen or seventeen years old, no more, with the hectic, unhealthy beauty of a consumptive. She was the chatelaine of all this decay.” Here is Carter to a T. There’s the post-modern privilege of insight conveyed through Gothic, 19th-century prose, the warm trickle-down of the faintly profane, the hint of screwball comedy, the hyper-real imagery, bursting with fluids. Carter made fairy tales scary again by making them stories we haven’t been told.

BOTTOM HALF: Ravenous dir. Antonia Bird (1999)

Antonia Bird’s Ravenous engages in a similar reconsideration of popular folklore, this time in the period setting of a remote California military outpost just after the Mexican-American War. Enter Boyd, played with spooky stoicism by Guy Pearce, a Lieutenant in the Army of the Republic of Texas who has been banished to Fort Spencer at the foot of the Sierra Nevadas for cowardice in the line of battle (a discharge that we learn, ere long, is far more nuanced than it seems). Amidst the gallery of misfits that Boyd encounters when he gets there, including an opium-addled private (David Arquette) and a schlubby colonel (pre-kiddie-porn-scandal Jeffrey Jones), comes another visitor to the Fort, the feral, malnourished Colqhoun (Robert Carlyle) — pronounced “Calhoun” — who regales the company with a hideous tale of wagon trains lost and survival gone savage. Robert Carlyle is magnetic; he and Bird have worked together in the past, and it shows. Carlyle exudes a stately menace that vows to come flying apart any second, recalling his turn as soccer hooligan Begbie in 1996’s Trainspotting; in Ravenous, he’s the perfectfoil for Guy Pearce’s more understated Lieutenant Boyd (in what film, I ask you, is Guy pierce not awesome?!). When things go south, they really do. The myth is question is Wendigo, a flesh-addicted man-beast of Algonquian derivation, which here manifests as a virus of sorts, and travels among the ranks of men, pitting them against each other. It’s this reinvention of popular myth that renders Bird’s film a companion to Carter — not to mention its wryness, its screwball bloodletting, its archetypal characters in moral upheaval. But where Carter’s collection explores femininity, Bird’s movie does the same for men — their ready grasp of evil, sure, but also their humanity. The movie had a mixed reception, probably because it’s extremely bizarre. It’s not quite a comedy, not quite a western and not quite a straight-ahead horror film, either; a blurred quality that could come off as tone-deaf. The soundtrack is a co-production between classical composer Michael Nyman and Blur-front-man Damon Albarn. The banjo, concertina and chorus of strings that usher Boyd onto the grounds of Fort Spencer are distinctly at odds with the period setting, the pastoral landscape, the horrors to come (the vibe is not dissimilar from Johnny Greenwood’s soundtrack to There Will Be Blood). Quirks infuse the script as well, such as when Colqhoun glibly quotes Benjamin Franklin at Boyd, “Eat to live. Don’t live to eat,” or when Jones’ Colonel Hart confesses: “It’s lonely being a cannibal. Tough making friends.” The colonel’s lament is not lost on the viewer. Ravenous is, at its core, a sad movie, more about the redemption of Lieutenant Boyd than Wendigo-fever or Calqhoun’s bloody crimes, and the ending delivers a punch to the heart. As much of a hybrid as Ravenous is, The Bloody Chamber, too, tricked readers, who were broadly uncertain how they should digest it — how its potent admixtures should cause them to feel. And that is the thing about legends, I guess: a good one always lives or dies on the strength of becoming a legend all over.

3rd Creature

TOP HALF: Sharp Objects by Gillian Flynn (2007)

Gone Girl was good, but Sharp Objects is better. Badly if stylishly misunderstood by Mary Gaitskill in her Bookforum takedown, Gillian Flynn has done for families what H.P. Lovecraft did for space; the menace comes not from the galaxy’s reaches but rather from inside the home. Home is where the heart is, sure, but only once mommy or daddy or hubby has cut it, still beating, from out of your chest. Home is also Missouri, when you’re reading Flynn, in this case the fictional town of Wind Gap, where reporter Camille, who grew up there, returns to investigate the murders of two local girls. The girls have been strangled, their teeth taken out; one of the girls, I’ve had trouble forgetting, is stuffed in the crawlspace dividing two buildings. Sharp Objects, as with other Flynn, is intensely, disturbingly violent, yet not; there are no murder-scenes and no Hostel-style torture, but violence, nonetheless, is there, like blood blooming up through a cocktail napkin. Case in point with Camille, the book’s anti-hero, a term the author has made sure can be liberally placed onto women as well (Walter White and Don Draper both pale to Camille). Fresh from the psych ward, Camille is a mess — she’s got some urgent mommy issues (Southern Gothic belle, Adora); her sister died when she was young and she hasn’t exactly had what you’d call closure; her living half-sister she’s deeply estranged from (the over-developed and uncanny Amma); while the woman herself is a certified cutter, her body a map of her failures and ills — “Whore” on her ankle, “Nasty” on her kneecap, “Girl” on the space above her heart. You know what someone like this needs? An extended return to the site of her trauma, a Victorian mansion with all of the trappings and Flynn isn’t scared to deliver her there so we can watch her world implode. Genre-wise, Sharp Objects is a mixture of Southern Gothic whodunit (think: The Little Friend by Donna Tartt), the family saga of psychological unease (think: We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson) and the serial killer thriller (think: Red Dragon by Thomas Harris). Stephen King blurbed it: “An admirably nasty piece of work…” And though it holds plenty of gruesome surprises — more murders uncovered, both present and past, a gangbang in a slaughterhouse — the novel’s true horror comes not from its filth but the filth that its players inflict on each other, the grim psychological scarring and torture. In many ways, this wouldn’t work were Flynn’s abusers not so real: Adora, the dark queen of bless-your-heart-manners “like a girl’s very best doll, the kind you don’t play with;” step-father Alan, “the opposite of moist,” reading equestrian books in the parlor; Amma, the preening and virginal whore, who Camille feels as much of a need to impress as recoil from in horror and run for the hills. Sharp Objects isn’t existential; you do find out who killed the girls, which fulfills the novel’s promise of a stomach-churning mystery. That pleasure, however, is nothing but plot. Camille’s demons, the people who reared and destroyed her, commit and recommit their crimes. Flynn’s view of the species is as bleak as Lovecraft’s, the signal difference being this: Flynn’s malign intelligences aren’t dressed up as humans and they’re not going to whisk you away to their planet. They are human beings — they’re your parents, your siblings. Relax: they’re here to take you home.

BOTTOM HALF: Surveillance dir. Jennifer Lynch (2008)

We’re all so hot on David Lynch (especially now with the Twin Peaks revival) , but nobody talks about Jennifer, really. That’s probably because she’s a far more transgressive and far less pretentious filmmaker than her father. Where David Lynch defaults to gleeful illogic and robo-tripping tracking shots, Jennifer Lynch maintains control, doling out tension by hot, bloody spoonfuls. Nowhere is this more apparent than in 2008’s horror-thriller Surveillance, for which Jennifer Lynch would become the first woman to receive the New York City Horror Film Festival’s Best Director award the year the movie was released. And none too soon for her career after the ruin of Boxing Helena (1993) — Lynch made her first movie at only 19 — about a wunderkind surgeon (Julian Sands) who turns the object of his affection (Sherilyn Fenn) into a quadruple amputee to prevent her from leaving him. The film wasn’t only hacked up by reviewers; the National Organization of Women said of it: “Nothing has come out in the past two years that reaches this level of misogyny. If Jennifer Lynch thinks this is what love is all about, I sincerely hope no one ever falls in love with her.’’ Some reviewers, however, had warmer opinions — of all reviewers, Janet Maslin, who wrote: “Ultimately, Ms. Lynch has nowhere to take her erotic parable except to a dead end, but she makes the unfolding of the story a spooky, engrossing process. There’s a lot more emotion to Ms. Lynch’s work than there is to her father’s… ‘Boxing Helena,’ while not the work of a Girl Scout, could also not be mistaken for a film made by a man.” So you can see why 15 years elapsed before she tried again, this time with a tale of two serial killers on a brutal rampage across rural Nebraska. The killers are pursued by Feds (Bill Pullman and Julia Ormond), who are keen to unravel their most recent killing through the shaky accounts of that killing’s survivors — a cop, a girl, a tweaker woman. How the film gets its title? The video feed that shows the survivors recalling their trauma, which Pullman and Ormond are watching off-stage in their government suits with an eerie detachment. Much like Flynn’s Sharp Objects, Surveillance also borrows heavily from the trope-cache of the serial killer thriller, albeit in a different setting — Surveillance pastoral, Sharp Objects domestic. The former’s a whodunit, too. Lynch’s villains, thrill-killers in burn-victim masks, are not who you don’t think they are. The violence they wreak at the start of the film is queasy-making and compelling while the origins of it — the trauma that drives it — are hidden by the killers’ masks. Sharp Objects, conversely, showcases the trauma, the violence born out of that trauma suppressed. Of Surveillance’s killers and their masks director Lynch had this to say: “People who hurt people more often than not have been hurt themselves… [The masks that the killers wear] sort of represented the monsters that hurt each of these characters when they were younger… I wanted to have [the masks] be something distorted and [look] as though two people might have applied [them] to each other in an erotic and lost state.” The pessimistic verdict of Sharp Objects and Surveillance:violence is our natural state,as foreordained as your next breath.

4th Creature

TOP HALF: American Psycho dir. Mary Harron (2000)

There’s a special schadenfreude in pointing out just how much better Mary Harron’s adaptation of Brett Easton Ellis’ novel is than the source material, primarily because of how much it would likely piss him off. Where Easton Ellis’ 1991 book is a paean to literary excess — too violent, too graphic, too long, too much — Harron’s adaptation of the life of Patrick Bateman, stock-trader by day, mass-killer by night, from a screenplay co-written by Harron herself and Guinevere Turner (who acts in the film) is a masterpiece of subtlety and narrative restraint. Take this stellar early scene: Bateman, played by Christian Bale with a faintly bewildered barely-thereness, takes a turn of his gorgeous Manhattan apartment while narrating in voice-over: “I believe in taking care of myself, and a balanced diet, and a rigorous exercise routine. In the morning, if my face is a little puffy, I’ll put on an icepack while doing my stomach crunches…” Follows then a scene of Bateman’s backside in the shower, the water streaming off of him as he soaps up his gluts and his shimmering flanks, hinting at the female gaze in a story that’s routinely horrid to women. “Then I apply an herb-mint facial mask,” Bateman tells us, “which I leave on for ten minutes while I prepare the rest of my routine. I always use an after-shave lotion with little or no alcohol because alcohol dries your face out and makes you look older…” And so do the cosmetic exertions continue until, finally, wiping stream from the mirror, Bale removes the gel-mask slowly. “There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me, only an entity, something illusory. And though I can hide my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyle are probably comparable, I simply am not there.” This scene sets the tone for the rest of the film as Bateman’s mask of sanity progressively slips. When Bateman kills a finance rival (Jared Leto) in an axe-murder scene that is loud-out-loud funny, his numerous blood-crimes begin to catch up in the form of a poker-faced private detective (Willem Dafoe). But Bateman can’t control himself. As he confesses to his fiance (Reese Witherspoon) during a lunch-date whose objective reality Harron later calls into question: “My need to engage in homicidal behavior on a massive scale cannot be corrected but I have no other way to fulfill my needs.” Those “needs” that Bateman talks about aren’t limited to those he hates. He kills homeless men, doormen, policemen and women — a great many women, we’re led to believe, many of whom he abuses pre-mortem. Herein lies a subtle yet crucial distinction that recommends the movie in relation to the book: while Bateman’s sex-crimes in the novel are such that they part with critique of misogynist systems and enter the realm of those systems themselves — he feeds his fiancé a urinal cake, he funnels a rat up a woman’s vagina — Mary Harron’s femicides are subtler and more frightening. Horror 101? Perhaps. And yet you can’t deny the chops of a scene in which Bateman abuses two call girls, largely because you don’t see the abuse, just the shaken call-girls as they leave his apartment; the way one of them rips down the money he offers on her way out the door with an obvious limp is worse than any torture scene that Easton Ellis slavered over. The same could be said for a subsequent scene, which is probably the movie’s most graphically violent: running naked with a chainsaw and covered in blood, Bateman chases a girl down a dark hallway, howling. It’s a pointed contrast to that first naked scene where Bateman does crunches, laves off in the shower, in perfect proportion, in perfect control, an object of the female gaze. Here, he’s stripped of everything but what drives him to hunt and make meat of his quarry. She lands a kick in self-defense. “Not the face,” he screams. “Not the fucking face you piece of bitch trash!” Harron succeeds in American Psycho where many men have tried and failed: to reckon with misogyny without voyeurism; not to preach or indict but to show us: this is. And you’re a person, too. So, feel.

BOTTOM HALF: Tampa by Alissa Nutting (2013)

Alissa Nutting’s novel Tampa fulfills the promise of Harron’s film by letting the female gaze run amuck in a woman akin to Patrick Batemen. Yet the book is devoid of ra-ra vindication; Nutting’s portrait is vivid and highly disturbing. The offender in question is called Celeste Price — or anyway she goes by name. She’s as much of an “entity,” finally, as Bateman, this time in the guise of a svelte 8th grade teacher (of English, of course) in the suburbs of Tampa. Yet instead of abusing and murdering women, Celeste seduces pre-teen boys — but not just any boy will do; Celeste requires one “at the very last link of androgyny that puberty would permit him: undeniably male but not man… [not yet wrestled] into a fixed shape.” Enter Jack Patrick, the hapless love object, whom Celeste wastes no time requisitioning wholly. A lot of uncomfortable trysting ensues, and emotional Russian roulette, and dark scheming, all of it done so Celeste can pursue her attraction to underage schoolboys unheeded. So where does the horror come in, you might ask? And that is partially the point. By immersing the reader sans hope of escape in the mind of boy-hungry sociopath — at one point, she dreams of a super-size boy band crushing her with their genitalia — Nutting makes us come to terms with a lot of our ass-backwards cultural values; older man + younger girl = sex offense, while older woman + younger boy = rite of passage. A social pathology starts to emerge, a tacit hebephillia (see the recent alt lit scandal) , and we are forced to reckon with what turns us on in startling ways. Yet that isn’t what most links Tampa with horror. Celeste Price, a mixture of Nosferatu, the Countess of Bathory and Patrick Bateman’s long lost sister, slathers on the facial creams (like virgin’s blood) to foil old age, and seems to draw vigor from those she corrupts. She also drugs her husband, Ford, from a stash of crushed-up Ambien to keep him submissive — and all this time you thought Gone Girl was the ultimate story of marital horror? Indeed, Tampa might find better company among straight-ahead horror novels such as Stephen King’s Doctor Sleep (2013)or Joe Hill’s NOS4A2 (2013)than Nabokov’s Lolita, to which it has been unbecomingly likened. More than Patrick Bateman, even, Nutting’s Price seems supernatural, in spite of being rooted in a hyper-mundane world. This might be because of the signature fact that Bateman in some sense can see that he’s mad, while in Celeste the need for tweens has crowded out pretty much everything else. Tampa, as well, has its own naked scene when Celeste’s inmost self is revealed to the reader. It’s as shocking as Bateman manhandling his chainsaw, chasing that girl down a dimly lit hall. What both portrayals share in common are darkly existential endings — though calling them “endings” might be to belie both Harron and Nutting’s artistic intent. In Harron’s take on Easton Ellis, Bateman’s privilege shields him from a moral accounting; in the film’s final sequence, he breaks it down for us: “My pain is constant and sharp and I do not hope for a better world for anyone. In fact, I want my pain to be inflicted on others. I want no one to escape. But even after admitting this, there is no catharsis. My punishment continues to elude me, and I gain no deeper knowledge of myself… This confession has meant nothing.” Celeste, too, is a prisoner inside her own skin, though she comes to the knowledge less cleanly than Bateman. The title of the book speaks volumes; though Celeste may not know where she’s going, we do. Tampa, the town where the novel takes place, is one among a legion like it. When Celeste Price has sapped it, she’ll move to the next, the “entity” of her — her punishing need — adopting new, infernal shapes. Harron’s and Nutting’s are stories of horror — or terror, more rightly — because they don’t end. The monster never gets its due, forever to wander the whorls of its maze.

5th Creature

TOP HALF: Reflections in a Golden Eye by Carson McCullers (1941)

Carson McCullers’ novel Reflections in a Golden Eye has got to have one of the best beginnings in literature: “There is a fort in the south where a few years ago a murder was committed. The participants in this tragedy were: two officers, a soldier, two women, a Filipino, and a horse.” And in a way that’s all you need to understand the book’s M.O. Facts are presented, affect is repressed — the prose is sharply uninflected — and Reflections, like all of our best horror stories, is a story of repression and destruction at its heart. McCullers’ fiction had always been dark — along with O’Connor, Capote and Welty she got lumped in as Southern Gothic — but Reflections is so unremittingly dark that it tips her, I think, into horror’s dominion. On the surface, the novel tells the tale of two marriages crumbling in on each other: the Pendertons — Weldon, a cuckolded Captain, and his gorgeous and castrating wife Leonora, who McCullers describes as a bit “feeble-minded”; and the Langdons — shattered Alison and happy-go-lucky Major Langdon with whom, as McCullers’ novel begins, Leonora is having a prolonged affair. The soldier is Private Elgee Williams — spooky, abstracted, obsessed with Leonora — the Filipino Anacleto, Alison Langdon’s domestic companion, and the horse Firebird, who belongs to Leonora. In among these charged relations — a soap opera cast, if there ever was one — are disorders, perversions, pathologies sundry, and attendant upon them the grotesque set-pieces that shocked the book’s readers when it was released; bestial sadomasochism, morbid exhibitionism, autogenous obsession and self-mutilation — enough grown-people issues with bad consequences to overflow the DSM. The Private covets Leonora and the Captain develops a thing for the Private while Leonora and the Major carry on with their affair with little thought to what it does to Alison Langdon, holed up by the fire, a garden shears held to her tenderest organs. And yet for all its luridness, the book is smoky and obscure. The Filipino Anacleto — one of Gothic’s most jaunty and memorable oddballs — illuminates the book’s obliqueness in the weird watercolors he makes for his mistress: “ ‘Look!’ Anacleto said suddenly. He crumpled up the paper he had been painting on and threw it aside. Then he sat in a meditative gesture with his chin in his hands, staring at the embers of the fire. ‘A peacock of a sort of ghastly green. With one immense golden eye. And in it these reflections of something tiny and — ‘ In his effort to find just the right word he held up his hand with the thumb and forefinger touched together. His hand made a great shadow on the wall behind him. ‘Tiny and — ‘ ‘Grotesque,’ [Alison] finished for him. He nodded shortly. ‘Exactly.’” The book is so disquieting because so much of it lies hidden. In her essay “The Grotesque in Southern Fiction,” Flannery O’Connor — who cared little for McCullers — explains this inclination in the following way: “…if the writer believes that our life is and will remain essentially mysterious, if he looks upon us as beings existing in a created order to whose laws we freely respond, then what he sees on the surface will be of interest to him only as he can go through it into an experience of mystery itself… Such a writer will be interested in what we don’t understand rather than in what we do… He will be interested in characters who are forced out to meet evil and grace and who act on a trust beyond themselves — whether they know very clearly what it is they act upon or not.” Reflections’ morbid subject matter renders it grotesque, of course, but also, too, O’Connor’s “mystery,” what drives the novel’s characters to “meet evil and grace and [act on trust] beyond themselves.” In Reflections, that “evil and grace” leads to murder. That, and nipple mutilation. Oh yeah, and riding horses naked. Too much dirty linen to ever get clean. And that, for the people involved, is a problem. The secrets they keep and that drive them to ill are secrets they can never tell.

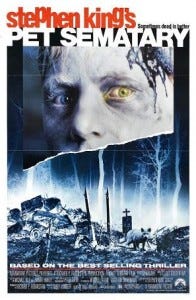

BOTTOM HALF: Pet Sematary dir. Mary Lambert (1989)

Talk about repression — sheesh. The book that Lambert would adapt by horror maestro Stephen King was, according to him, the only one that King at first refused to publish. “If I had my way about it, I still would not have published Pet Sematary,” commented King. “I don’t like it. It’s a terrible book — not in terms of the writing, but it just spirals down into darkness. It seems to be saying that nothing works and nothing is worth it, and I don’t really believe that.” Stephen King has been known to exaggerate some — indeed-y-do, as King might say, he rakes in nine figures for doing just that — but given what the book contains, moreover what Lambert would do with the movie, the story is without a doubt the most heinous nightmare he ever dredged up. It follows the hugely unlucky Creed family, who move to a new town in (you guessed it) Maine so that Louis, the dad and a medical doctor (played by Dale Midkiff with glassy-eyed stiffness) can work saving lives at the college in town. The Creeds’ misfortunes first begin when the family maid hangs herself in their basement. After having a half-assed death talk with their kids — apropos of which Rachel, the good doctor’s wife (Denise Crosby), recounts her sister’s dwindling from spinal meningitis in a scene in the film that reduced me to tears of abject primal terror the first time I watched it — the Creeds assume that all is well until the family cat goes missing. Louis finds him later on, pancaked by a passing truck. But because he was crappy at giving the death talk (not wanting an even worse reprise, I guess) buries him not as a pet should be buried, in holy ground for hounds and goldfish, but in a sacred place “beyond” which a neighbor reveals to the doctor, ere long, was a mystical hotspot for Micmac interment. (Always count on Stephen King for political/cultural/racial tone-deafness) But the cat comes back/ the very next day/ yeah, the cat comes back/ they thought he was a goner — etc. Needless to say, he is no longer cuddly. And so begins the film’s descent into supernatural hard knocks never-ending for the Creeds, the more so when the viewer learns that the burial ground, in fact, is “evil” and is drawing the family one by one into its orbit of decay. This sounds like fairly silly stuff, but Mary Lambert manages to make it resoundingly, viscerally scary. To certain horror geeks like me, Lambert’s an intriguing figure; she directed this movie, its terrible sequel and from there made it onto the B-list full-time (Urban Legends: Bloody Mary and Mega-Python vs. Gatoroid are two of her newest artistic forays) Which strikes me as an honest shame. There’s a funhouse overripe-ness, an uncanny fuzz, to the way that the movie was shot and directed. Nothing could be worse to watch in my twelve-year-old mind than that dwindling sister, and the scenes with the foul, resurrected tot Gage (Miko Hughes) are enough to make anyone never have kids — not to mention the gory dream-revenant Pascow, and the satanic cat, and the shin-slicing scene. To someone who understands how hard it is to chill the blood of someone else, Lambert’s film succeeds in spades. The film is a companion piece to Carson McCullers’ subtler creation in the sense that the latter makes good on the former. The travails of the Creeds are the Pendertons’ and Langdons’ liberated from the prison of tasteful restraint. Zombification, family trauma, the death instinct and, worst of all, the act of harming those you love are buried deep down in McCullers’ novel; in Pet Sematary, Lambert resurrects them, parades them around, gives them teeth and a scalpel. If Freud’s das Unheimlich is partly defined by a long-dormant yet nascent belief in the “old, animistic conception of the universe,” which includes “the omnipotence of thoughts, instantaneous wish fulfillments, secret power to do harm and the return of the dead,” then Pet Sematary could be defined, too, as the latent content that Reflections represses. If McCullers wrote the eulogy, then Lambert says the incantation.