interviews

Michelle Tea on Archiving Queer History that Is Often Erased

The author of ‘Against Memoir’ discusses curating an imprint that champions emerging LGBTQ+ writers

I was introduced to Michelle Tea and Sister Spit in the damp basement of a South Brooklyn performance venue on the second of three quirky OkCupid dates with a literal fire breather. It was sometime around 2010 and I was new to queerness and to Brooklyn. When my date proposed the performance, I tried to talk her out of it because I had to hop on the subway by 5:15 am the next morning to commute from Brooklyn to my teaching job in the South Bronx. She persisted and I met her a few hours after school let out, wearing a left-cocked New Era cap, a light blue tie in a half windsor knot, and a crisp, colorful Uniqlo button down. This was the first literary performance I had ever attended.

I didn’t speak a word to my date after the performance started. I couldn’t take my eye off of the stage. It was one of the first times I was hearing other folks who were gender non-conforming, queer, and people of color speak candidly and humorously about their experiences. This wasn’t something I had access to growing up in Seattle or in college or grad school in California. It would take 5 years for me to start reading and writing my own poems but this Sister Spit event planted seeds that eventually flowered.

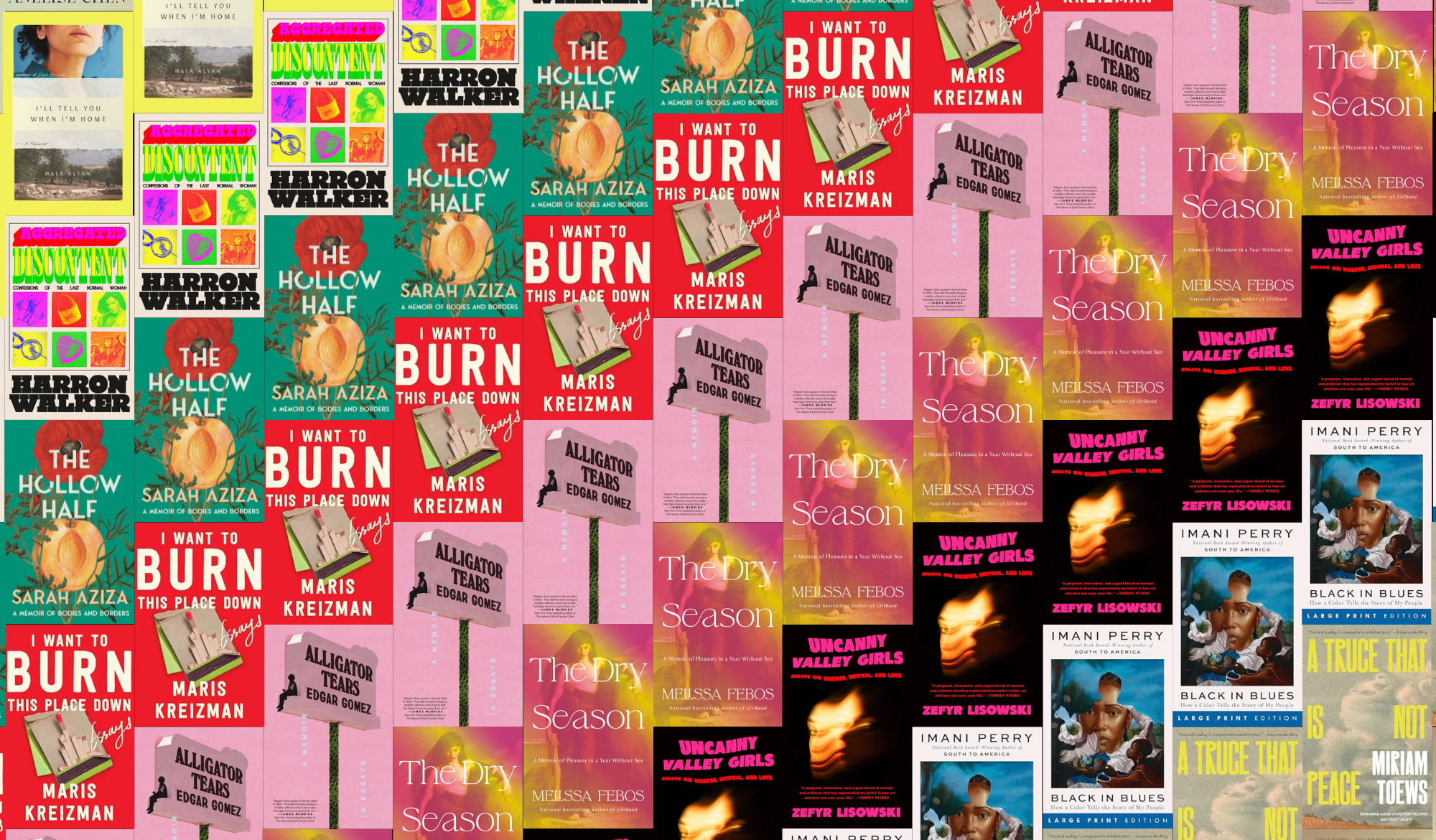

Michelle Tea founded the Sister Spit tour and is a prolific author, poet, curator, and performer. She is the curator of the Amethyst Editions imprint at Feminist Press, “champion[ing] emerging queer writers who employ genre-bending narratives and experimental writing styles, and complicates the conversation around American LGBTQ+ experiences beyond a coming out narrative”. Her latest book, Against Memoir, lets years of queer journalism reverberate in a single volume. Long-form journalism pieces about Valerie Solanas, the HAGS, gentrification, addition, dating, family-building, queer art, transphobia, and Trans Camp, speak to each other. I jumped at the opportunity to hop on a call with Michelle to talk to her about her intersecting writing, publishing, and performing careers and her approach to archiving queer history that is often erased.

Candace Williams: How is life in LA? Folks are moving there left and right.

Michelle Tea: It’s really true. A big reason we moved here is because so many of our friends in San Francisco had moved here. San Francisco is just more and more a ghost town. I mean, I still have friends there, too, but just the pull of it was really strong. I mean, it’s cheaper. In San Francisco, it felt like the walls were closing in. It’s a small city. There’s only so much space and tech gentrification has been bad for so long. After a certain point you just recognize that they won and there was no coming back from it. Then, it was just kind of depressing to live in a city that used to be great.

I really like LA. I like the weather. I like all of the greenery. People who don’t live here think of freeways and sprawl, but there’s so much nature here. People hike way more here than anyone I know hiked in San Francisco. There’s a lot of opportunity here. The dominant industry is the entertainment industry — which I think is really interesting and fascinating and inspiring, unlike the tech industry, which I just feel like is boring and alienating.

CW: I’m in awe of your curation career as well as your writing career. You’ve created many different reading series in different settings, from libraries, to bookstores. You had the Sister Spit/City Lights imprint and now you have Amethyst which sounds awesome because it’s my birthstone.

MT: Aquarius? Me too, high five!

CW: Yes, high five! Can you talk about that journey? Has it mirrored your writing career? What do you love about it and what’s hard?

MT: My curating and my writing kind of happen side by side because I started writing by going to poetry open mics in the 90s in San Francisco when they were really fun. There was so much variety in the kinds of writing and really high energy… it had the energy of a punk show which is not what you would think about from poetry. My performing happened at the same time as my writing did. It all happened in community. In San Francisco at the time, many different venues would do curated shows. The Bearded Lady would have shows. The Luna Sea Woman’s Performance Project would have shows. You would wait to get invited to one of these shows and that’s how I came up as a writer. It was really fun for me. I didn’t go to college or anything. This was how I learned how to write better. My canon was the people around me who were also reading their work and we were inspiring each other and it was a super cool time.

Sister Spit came out of that. It began as an open mic. There were tons of open mics in San Francisco and they were very straight and they were very dude heavy. There were definitely tons of women and there were some queers and some people of color. I realized I liked going there because I had a big chip on my shoulder. I liked hearing some misogynist asshole and then heckling them and getting in a fight while I was drunk. The other queers and women who went to these, they kind of had to be smart asses themselves to kind of do it. Sidney Anderson (who I did Sister Spit with) and I , asked “Where are all the other queer female writers?” because the city’s filled with them and they’re not coming to these things. They’re not coming cause they don’t feel welcome and it makes sense that they don’t feel welcome. You had to really fight for a space there. Then once you did, everyone loved you. It was just like you got jumped into the gang or something. Everyone loved you. So we started doing Sister Spit and at our first open mic we had 20 people signed up.

CW: Wow. That’s an amazing turnout for an open mic!

MT: It was. It was really cool. We did that for a couple of years and then got burned out. I’d been playing in a band and our band went on tour even though we were not ready to go on tour. We were not that good. We did it anyway and I loved being on tour and that’s how the Sister Spit tour started. I wanted to have that experience again, but I didn’t want to be in a band anymore.

CW: That’s really brilliant. All of us want to be in a band, right? All of us want to tour. It must be interesting to tour with writing and bring intellectual light to audiences. Was it easier than touring with a band?

MT: It was easier to get gigs. It was easier to get audiences. If you’re a band, you’re in a kind of niche of whatever music you play and the scene you grew out of. We were queer writings and at that moment, spoken word was really popular, and slam was developing. There were slam teams in different cities that we could contact and say, “Hey, can you help us put on a show?”. Then, we’d put the word out in gay newspapers. It was better than just like being a weird math rock band.

I’m really psyched that it’s still happening. I turned it over, and it ended up becoming part of Radar Productions, which is the literary non-profit I started in San Francisco. After a point, after doing so much curating, literally for decades, I had a grant writer who’s this older gay man who is wonderful, kind of grab me and be like, “Do you understand that you are doing the work of a non-profit but with zero resources and no pay?”. He helped me create a non-profit to stick all of my projects under and get funded and it changed my life. But I had to hand it off when I moved to LA. I handed it to this younger, amazing curator and writer named Juliana Delgado Lopera. Her book is coming out on Feminist Press in a year or two. Under her watch, it’s become all queer trans people of color. It’s awesome. She’s just doing great stuff with it.

If you’re a marginalized person, you’re telling your story. You’re empowering other marginalized people. You’re setting the record straight from history and that can be politically powerful.

CW: How did Amethyst come about?

MT: I’m in touch with so many writers and I get to know what they’re working on. and The Radar Reading Series was another project that I ran it for 13 years. It was a monthly reading series at the San Francisco Public Library. For six years, I ran the Radar Lab, which was a free queer-centric writer’s retreat in Mexico. It was open to anybody who’d ever read at Radar or performed with Sister Spit. They could submit their writing and their proposal. We would judge the work anonymously and then writers would go to Mexico and work on their pieces. I learned about all these works in progress and I just wanted to publish them all. It might be a weird, creepy, narcissistic sort of impulse, actually. I see these writers who really inspire me and then I want to do something with them. I guess it’s like a producing impulse. I’m like, “You’re amazing. I want to do something with you. What do we do?”.

For a minute, we thought about doing our own press, and I had a really illuminating meeting with Dave Eggers about how he started McSweeney’s and what their business model was. I realized I could accomplish what I wanted to accomplish by hitching onto an existing press instead of recreating the wheel. I was really inspired by Little House on the Bowery, which is a Dennis Cooper’s imprint with Akashic books. I realized, “Oh, other writers have done this. It’s not like I’m making this up.”

I went to City Lights and I met with Elaine Katzenberger and she loved the idea. I love City Lights. I always felt really supported by them as a writer it would be good for them to have an overtly queer and female project in their roster because they are kind of known for their straight white dude projects.

We did that for a while. Then, I started publishing with Feminist Press. They picked up my book, Black Wave. Editor-in-chief Jennifer Baumgardner and I hit it off and it just seemed like I was going to start publishing with them and working closely with them and maybe it would be a better fit and make more sense to kind of move my publishing impulses over to Feminist Press.

With City Lights, you get great distribution and great publicity. City Lights is so impressive and historically important. Feminist Press is able to pay a little bit of an advance. Super tiny, but it’s always been part of my work to try to get money to writers, so that was really attractive. Amethyst is a specifically queer imprint within Feminist Press.

What binds all the Amethyst titles together is that it’s truly queer, outside the LGBT mainstream, and there is a radical politic embedded in all of the work, even if the story isn’t necessarily about radical politics.

CW: So, let’s say it’s 20 years from now and people are looking at all of the Amethyst titles that have come out for the past 20 years. What do you want people to think about the imprint and the work as a body? What do you want the work to do in the world? I’m thinking about something like Kitchen Table Press, which I’m really thankful for. The press doesn’t exist anymore, but I go to the Herstory Archives and I read Audre Lorde and I read Barbara Smith and I realize, “Wow, Kitchen Table published all of these great books and all of these great people and their work still stands up”. What kind of vibe or idea do you want people to get in their mind when they hear of your imprint down the road from now?

MT: The thing that really binds all the work together is it’s queer. It’s truly queer. It’s outside the LGBT mainstream, and I think that there is a radical politic embedded in all of the work, even if the story isn’t necessarily about radical politics. Radical politics are embedded in the hearts of all the people that we publish, so they come through in the writing in one way or another. There’s also humor. I love humor. This world is so fucking hard and queer humor can be a dark humor, it can be a gallows humor, it can be a surreal, absurd humor, but I love humor and I think there’s queer humor in all of the work that we publish.

CW: After reading Against Memoir, I started thinking more critically about addiction, and the role it plays in a lot of queer communities. One thing I really appreciated about the book is that I think you’re constantly acknowledging and processing both sites of oppression, but also your sites of privilege in relation to people and events you are archiving. I feel like you were able to capture part of the Camp Trans story that has been lost, simply because you spoke to people who were there. There’s privilege in being the one to deliver that message. What steps do you take to make sure that you’re writing about people and not writing over people?

MT: I felt hyper-aware that I was kind of a double outsider at Camp Trans. I’m not a trans person. I’m cisgender. So, I’m bringing that privilege with me, and then I’m there as a member of the press. My approach was to actually use the direct words of trans women at Trans Camp instead of paraphrasing them. I did not want to filter what they have to say through me. I wanted to center them and give them space

I’m really grateful for the Believer. They run long form journalism even though it’s not the traditional way to do things. The traditional way to do things is for editors to ask, “Can you paraphrase that?”. I think journalists and editors can mistakenly think that’s part of their job, to distill what everyone’s saying, and then spit it out in their own words.

When you’re talking to people who are from a community that you’re actually not a part of, and you actually have more privilege and access that these folks, I think it’s really important to just give them the space to actually say shit in their own words. It’s way more powerful. It’s more effective. It’s more interesting.

The HAGS piece was similar. I have privilege as a survivor. I didn’t go down that rabbit hole so deeply that I couldn’t get out. Also, as somebody who just didn’t have it quite as hard as they did growing up in the world. I am cisgender and many of them weren’t. I think they identified as “butch” and some of those folks have since transitioned. Who knows what the folks who passed away would have ended up identifying as, were they allowed to kind of keep living and evolving.

That was really hard to write. I felt intimidated by the weight of history and representation and knowing that people close to them already felt burned by the media because the mainstream press, like the Daily Paper, picked up the story in a very sensationalistic way when members of the HAGS died.

I interviewed a lot of people who survived them and loved them and wanted to do right by their story, and so it was overwhelming. I did a lot of interviewing and I collected tons of interviews and then I just sat on it and I just didn’t write the story for awhile. The California Sunday Magazine was interested. I thought it was gonna be a really long piece. I finally get it together and write it. It’s epic. When I finished it, I laid in bed and spent the afternoon crying, which I don’t do. I am not a laying down during the day and crying person. I was really, deeply exhausted from it. Then, it turned out I was super wrong. I only had 3,000 words.

So then, I was intimidated in a different way, like “How am I gonna cut this down?”. I cut it down and it was horrible. It read exactly the way I didn’t want it to read. It was like, “Look at these people. They were queer. Crazy, they did drugs and died. The end.” There was no context. There was nothing of my own story in it. I feel like my story helped contextualize the time.

CW: That makes sense. Stories are lineages right? When you think about the lineage of HAGS, part of it is you. Even though you were coexisting, you were also part of this movement. So, what did you do?

MT: I just pulled it. I was like, “You can’t run it. I’m so sorry. It just doesn’t work like this and I’m sorry that I wasted your time.” Then, I contacted the Believer. I’ve published with them before and it’s always been a great experience with them giving me lots of space and be really open to queer content. Then, in the process, I had this book, Against Memoir, coming out. I had made this plan with Feminist Press to publish a collection of my journalism pieces and they wanted new work. I’m really happy for that initial “yes” from California Sunday because it got me to do it and I’d thought about it for so long.

I feel like the piece is about what I experienced in San Francisco in the 1990s in general. I feel like I experienced an evolution and a movement and it is lost to history. It did not get recorded.

When you’re talking to people who are from a community that you’re actually not a part of, and you actually have more privilege and access that these folks, I think it’s really important to just give them the space to actually say shit in their own words. It’s way more powerful. It’s more effective. It’s more interesting.

CW: In a previous interview, you said that you reject the activist label for the work that you’re doing now. Earlier in your life, you were going out to protests, and mobilizing artwork, and doing all these things that were a direct and critical response to events and issues. Now, the focus of your work has shifted. How does the memoir fit in to your idea of what literally organizing is, and is there such a thing as literally activism?

MT: I think that there can be such a thing as literary activism and I think that memoirs are a huge part of literary organizing in a political sense because it’s people telling their stories and that’s always really powerful. If you’re a marginalized person, you’re telling your story. You’re empowering other marginalized people. You’re setting the record straight from history and that can be politically powerful.

But for me, having done actual activism and now, as a writer, I have a literary career. So when I’m writing books, that is so self serving. It just can never feel like activism to me. I know people are paid to organize. I think that’s awesome and it is still organizing but for me, I just feel like I’m a writer. My politics come through in my books. I follow my creative impulses and if my writing happens to have political and activism resonance, I’m happy about that but I don’t set out to do that. It’s a side effect of me following my creative passion.

There’s this march for families against ICE here in LA on Saturday and so on Friday, me and my wife and my son we’re gonna make signs and we’re go to the march. That feels like activism to me even though I know that in a sense, my writing could possibly be more effective in some ways. I don’t know. It is weird.

CW: So let’s say tomorrow, someone gave you a lot of money and says, “Michelle, organize the next massive queer festival.” Do you have a name for it? Do you know what the vibe would be like? Because I’m getting the sense that you learned a lot from Trans Camp and you learned a lot from the Michigan Women’s Music Festival.

MT: Oh, I wish someone would do that. Oh my god that would be amazing and fun! It would be very inclusive, and accepting, and it would be very kind of punk, and it would have really fantastic art because I actually think I have really good taste. I would pay everybody and that would be cool.

I would love to have an opportunity to bring so many of the people and performers in all different mediums that I love together. I don’t know, I would have Seth Bogart and Peggy Noland design the stages and I would have Sons of an Illustrious Father play, and I would get other people to curate because that’s important. The literary stage would really be my baby. I’d have Dynasty Handbag, and I would have Narcissister, and I would have lots of performance art and have it be super weird. It would be a queerdo fest.

CW: That’s awesome. Would you limit it by gender at all?

MT: No, I wouldn’t. I really wouldn’t. I did that for so long with Sister Spit and it felt appropriate for the time. But I don’t really feel like it’s where I am right now. I would want all genders present. I feel like when you start gender segregating it inevitably just hurts trans communities because you’re leaving people out. Trans people are a part of my community of all genders, and so I would always want to include those voices and those people.

I just think that ultimately what people want is to feel safe and and to be surrounded by like-minded people who have their best interest at heart and share their values, and I just think if you’re using gender as a litmus test for that you’re fucked. It just doesn’t work, it’s broken. I understand why women organized in that way historically but I just feel like it doesn’t work anymore. Arguably, it never worked. It definitely doesn’t work today.

Memoirs are a huge part of literary organizing in a political sense because it’s people telling their stories and that’s always really powerful.

CW: Have you written any poetry lately? How does that process differ from writing an essay?

MT: It feels different in my body. It feels different in my mind. It requires almost a different lifestyle. I was just having this same conversation with Maggie Nelson who has written beautiful volumes of poetry and just doesn’t really like poetry anymore. For me, I need to be in a certain mindset and I need to almost structure my days in a different way to allow for what to me feels like the more subtle inspiration towards poetry to come into my body. The inspiration towards a poem has felt like it’s a particular feeling for me.

What has happened, for better or for worse, is that I have filled my days up in a particular way that blocks that vibe from coming in. I don’t feel great about that and I do think that if I wanted to I could change that. I think that if I made the intention to write more poetry and began reading more poetry again, and immersing myself in poetry more, that vibe would come back. I think it’s so cool that someone like Eileen Myles is able to continue producing poetry while they write novels and screenplays. I love poetry.

I feel like my focus is more on trying to make TV and film projects happen, and I feel less focused on what my next book will be. I still need to be writing, it might actually be a nice moment to allow for poetry to come in, and to have that be my literary output.