Lit Mags

My Last Story

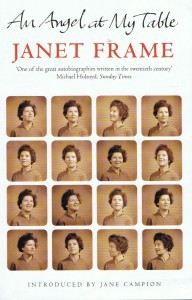

by Janet Frame, recommended by Etgar Keret

EDITOR’S NOTE by Etgar Keret

Where does the need to make up a story come from? I think that every time I’ve ever read a story, that question echoes in my mind. What is it that made the writer spin such a complicated plot and invest his entire being in developing characters he never knew instead of devoting the same time and energy to, for example, putting together a tasty salad or playing an exciting game of Scrabble on the living room floor? That’s why I have always been interested in stories that have to do with writing. Stories that remove the insoluble question of the nature of creativity from its permanent blind spot and place it front and center.

The problem with texts of that kind is that, in many cases, they are clever, but almost never moving. As if that reflexive sort of writing moves writers to their mind and away from their heart. There are, of course, exceptions, and Janet Frame’s “My Last Story” is one of them.

I don’t know what makes it work so intensely. Maybe it’s the refusal to write what stands at its center; maybe it’s the fact that despite its title, it isn’t really a story in the fictional sense of the word, but rather a compilation of apparently actual events in Frame’s life: a collection of experiences, memories and emotions, and not of invented happenings she could have created from the same raw materials.

In the 1940s, Frame was institutionalized in mental hospitals, diagnosed with schizophrenia. When her first collection of stories, which ends with this one, was published in New Zealand, its great success saved her from having to undergo a lobotomy.

Like all writers, Frame had no pragmatic reason for making up stories, but the fiction she created had a clear and pragmatic effect on her life: writing kept her complex, sensitive mind whole.

– Etgar Keret

Translated by Sondra Silverston

My Last Story

Janet Frame

Share article

I’M NEVER GOING TO WRITE ANOTHER STORY.

I don’t like writing stories. I don’t like putting he said she said he did she did, and telling about people, the small dark woman who coughs into a silk handkerchief and says excuse me would you like another soda cracker Mary, and the men with grease all over their clothes and lunch tins in their hands, the Hillside men who get into the tram at four forty-five, and hang on to the straps so the ladies can sit down comfortably, and stare out of the window and you never know what they’re thinking, perhaps about their sons in Standard two, who are going to work at Hillside when it’s time for them to leave school, and that’s called work and earning a living, well I’m not going to write any more stories like that. I’m not going to write about the snow and the curly chrysanthemums peeping out of the snow and the women saying how lovely every cloud has a silver lining, and I’m not going to write about my grandmother sitting in a black dress at the back door and having her photo taken with Dad because he loved her best and Uncle Charlie broke her heart because he drank beer. I’m never going to write another story after this one. This is my last story.

I’m not going to write about the woman upstairs and the little girl who bangs her head against the wall and can’t talk yet though she’s five you would think she’d have started by now, and I’m not going to write about Harry who’s got a copy of We Were the Rats under his pillow and I suppose that’s called experience of Life.

And about George Street and Princes Street and the trams up to twelve. I’m not going to write about my family and the house where I live when I’m in Oamaru, the queerest little house I’ve ever seen, with trees all round it oaks and willows and silver birches and apple trees that are like a fairy-tale in October, and ducks waggling their legs in the air, and swamp hens in evening dress, navy blue with red at the neck, nice and boogie-woogie, and cats that have kittens without being ethical.

And my sister who’s in the sixth form at school and talks about a Brave New World and Aldous Huxley and DH Lawrence, and asks me is it love it must be love because when we were standing on the bridge he said. He said, she said, I’m not going to write any more stories about that. I’m not going to write any more about the rest of my family, my other sister who teaches and doesn’t like teaching though why on earth if you don’t like it they say.

That’s Isabel, and when it’s raining hard outside and I think of forty days and forty nights and an ark being built, when it’s dark outside and the rain is tangled up in the trees, Isabel comes up to me, and her eyes are so sad what about the fowls, the fowls I can see them with their feathers dripping wet and perches are such cold places to sleep. My sister has a heart of gold, that’s how they express things like that.

Well I’m not going to do any more expressing.

This is my last story.

And I’m going to put three dots with my typewriter, impressively, and then I’m going to begin …

I think I must be frozen inside with no heart to speak of. I think I’ve got the wrong way of looking at Life.