Interviews

Nicole Krauss Learns to Love Uncertainty

Nicole Krauss discusses breaking old forms and learning to embrace uncertainty in fiction and in life

Nicole Krauss’s latest effort, Forest Dark, is a story of light buried in bramble. Flitting between the narrative of Nicole, a young-ish writer seeking inspiration in the mystical history of Tel Aviv, and Jules Epstein, a retired lawyer who gets mixed up with a rabbi’s daughter and her film depicting the life of David, the novel is both inviting and intimidating. Shifting from the metaphysical nesting doll sensibility of her astonishing Great House, Krauss created a vast landscape for her characters to inhabit, and the largness of her Tel Aviv allows Nicole and Jules to seem insignificant, but not unimportant. It’s a difficult balancing act to pull off, and all the mystery and difficult questions that follow give way to something that feels real, adult, and undeniably true to life.

With each release, it becomes clearer and clearer that Krauss operates on her own level. A capital–I Important writer, her language is both lyrical and pained, her prose placid but incisive. From The History of Love on, each novel has read like a fully-formed modern classic, à la the work of Marilynne Robinson, Jeffrey Eugenides, and as mentioned in the interview, Rachel Cusk and Ben Lerner. Reading her work is often a transformative, engaging experience, so when the opportunity came up to interview her, I jumped at the chance. Despite her being rather busy on a world-wide book tour, she graciously took the time to correspond with me by email from England.

Eric Farwell: Your last book, Great House, was just as complicated as this one, but there seemed to be more certainty in place. In other words, as nuanced or heady as the narrative might get, there was an understanding that you were always guiding the reader to where they needed to get. Forest Dark is a lot more open, and reads, at least to me, like a mix between Rachel Cusk and Ben Lerner. There’s nothing to trust, because the protagonists are perhaps even less aware of their world than the reader. I wanted to start by asking you to walk through how this became the novel.

Nicole Krauss: I think that if a novel works, it’s because a sense of trust is created in the reader. The best kind of writing gains that trust within the first page and then it builds: trust that wherever the narrative is going, it will be worthwhile, and that the world created on the page is made live because every aspect of it has been deeply considered and thoughtfully conceived. As a reader, I find that the more space I am given to make connections on my own — in other words, the more the author trusts me, in turn, to think for myself and to understand — the deeper my experience, and often the more revelatory.

As a writer, the trust I might create in the reader has to begin with my own faith in the soundness of my process. And this time, that was a bit smoother, having already been through it numerous times now with my previous novels. I don’t outline or plot my books beforehand; I try and let things be as organic and intuitive as possible. I set out not knowing where the book will take me, and for a long time I sit with that uncertainty, sometimes for years. The act of discovery is very important to me, as it allows me to figure out the most authentic resolution for the various concerns and urgencies that inevitably arise when I’m working out something new. I had more anxiety about my process when I started out writing novels, particularly as their structures become more complex, but now when I start with many disparate stories or ideas, I trust that I will uncover connections, echoes, patterns, and meaning that eventually create a subtle sense of the whole, one I would never have arrived at had I set out armed with a plan and many certainties.

EF: With that being said, there really does seem to be a more open, less certain sensibility here. I’m curious if you maybe felt boxed in at the end of Great House and wanted to pivot.

NK: Writing as I know it has always been a process of feeling boxed in, and searching for a way out. My decision to shift from poetry to the novel at 25 came about because I felt boxed in by the form, or my own use of it. While there are great poets that can fit infinity into a few stanzas, I found I wasn’t able to. Brodsky had encouraged me to write formal verse (with the valid belief that one should know what one is being freed from), and as my poems got smaller and tighter, I felt that there was increasingly less space for me to breathe in them. Less space to be free, and for me, at the bottom of writing, there need always be a straining toward new freedom. When I started my first novel, it was exhilarating to flood into new conditions — into prose, and length, and the slow evolution of ideas and feeling that novels allow for. I think what you’re maybe sensing is my view on life, which continues to grow and change as I do. While I think it’s important to have cohesion and a strong narrative angle, I also value having the freedom to break old forms that feel too limiting or closed. Thus the sense of openness. It’s something that I don’t want to give up.

While I think it’s important to have cohesion and a strong narrative angle, I also value having the freedom to break old forms that feel too limiting or closed.

EF: While that desire may be present and rightfully persistent, one thing that hasn’t changed is your penchant for historical connections — both seeking and having. Both Nicole and Epstein seem to be daunted, or even annoyed by how immense the history of Israel really is. How did you go about navigating that balance between instilling a sense of the monolithic past and moving the modern narrative forward in this looser style?

NK: We have been telling the same stories for many thousands of years, and these stories either constitute cultural memory or history, depending on how you look at it. The stories, and our attachment to them as the foundations of our identity, feed us deeply, but they also constrain us. We feel we are something continuous with the past, and belong to a larger narrative, but we also — some of us, at least — strain at the bit, all too aware of how these narratives bind us, and limit the openness that might otherwise have been our future.

We live in a moment in history when we feel, as a species, that we know more about our pasts than we ever did. We are comforted by all of our knowledge about the past, and our knowledge about our present. And yet as valuable as the Internet may be, it also tricks us into feeling that we possess far more understanding than we really do. The comfort that being able to Google search anything and everything brings reflects, I think, an anxiety about not knowing. And though of course I value factual knowledge, I think that we have made something of a religion of it in our time, and the unquestioning way we prize it, and cling to the myth that we entirely possess it, means that increasingly we are turning away from the unknown. In a sense, we have been taught to equate the unknown with ignorance, when in truth we know very little. Contemplating the unknown, and the vast scope of our world and our being — the universe, ourselves, our sense of what is ‘other’ than us — may be unnerving, but can deepen us immeasurably, and change us. In my writing I try to carve out space for that — for what Keats called dwelling in uncertainties. Because I think what should be most extraordinary about the time in which we live is the use of our knowledge to remind us that our sense of reality is objective, that our narratives, both personal and political, are flexible, and that if we approach them with the modesty of understanding how they dictate us, and the courage to understand that we can alter them, we might arrive at better ways of being.

EF: In Forest Dark, Kafka seems to be used as the historical glue, so to speak, at least in the Nicole narrative. What I found to be most interesting about your use of him was the care you took to paint the struggle he had with desiring to write, but worrying it might not have true value. At this point, with four books out in fifteen years, are you at all facing those same concerns?

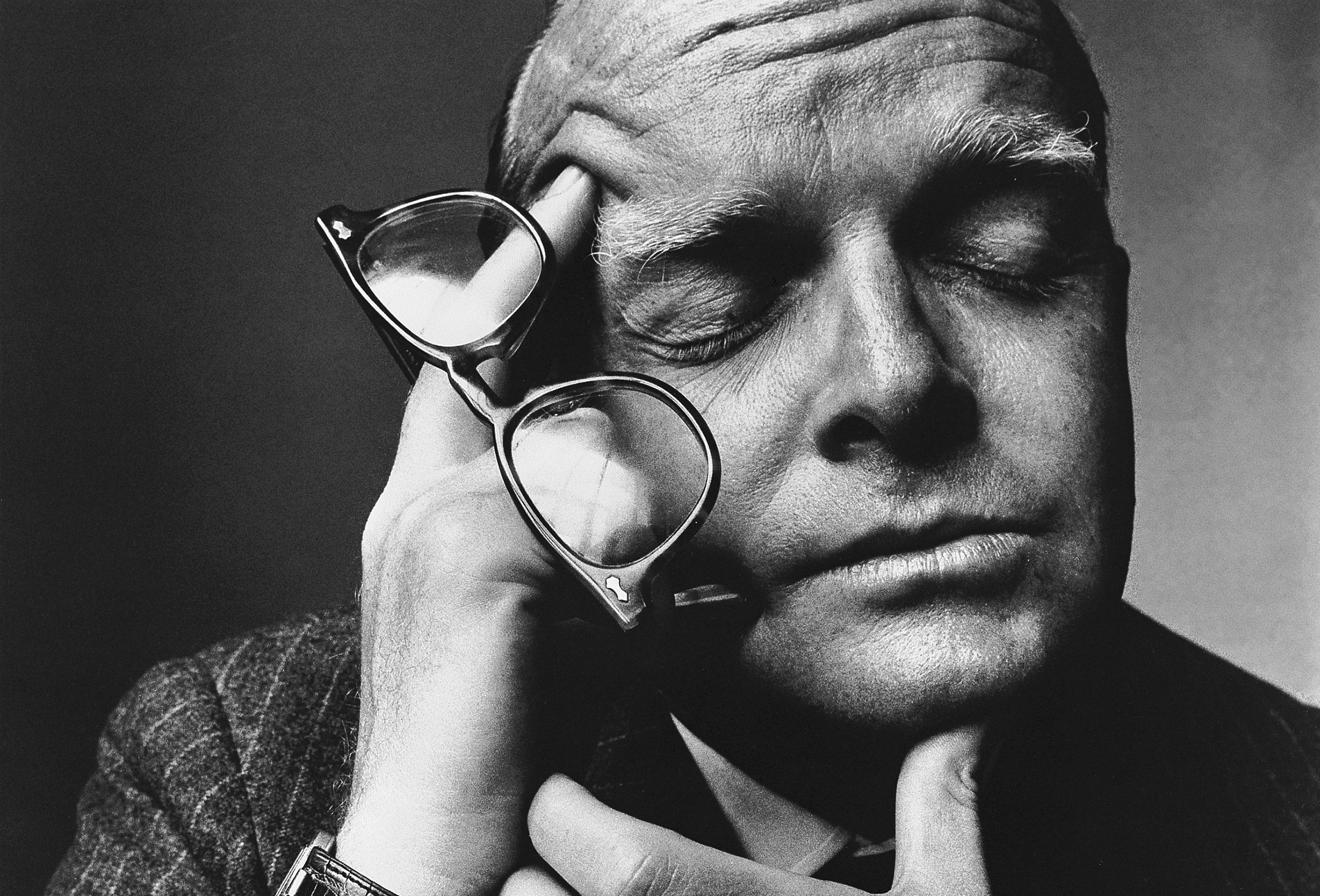

NK: For better or worse, I have no imagination for the posterity of my work. I’ve just never really given much thought, or have not allowed myself much thought, about how long my work might be read beyond the scope of the present. That being said, naturally I have struggled with even the question of its value in the present. My anxieties rose many times to a peak, but as time passes I feel I’ve better learned how allay them. Helpful with this were some rules of thumb that Philip Roth once wrote down for me years ago: 1) It’s not for you to measure yourself against others, 2) It’s not for you to judge the work, 3) Just tell the story, 4) It’s not going to get any easier. Resign yourself to this.

With each book, I’ve grown more comfortable with that long dwelling in uncertainty that it takes to write the kind of novels I want to write. I do my best to produce the most honest, authentic work that I can. And I always go back to that stunning last line of Rilke’s poem, “Archaic Torso of Apollo”: You must change your life. I think it’s the imperative of literature, but if you are going to be able to move the reader to change, then you have to begin within yourself and your work, however vulnerable a position that may put you in.

EF: Shifting a bit, I wanted to ask about Nicole’s ending, which is disturbing in its lack of resolve. As someone who often writes of a sort of light, who often rewards characters with a sense of comfort or palliation, I wanted to know if this ending was difficult to render.

NK: It didn’t feel disturbing to me when I wrote it, but perhaps that’s because I don’t find a lack of resolve disturbing — we live with that lack all the time. And is it not a form of resolution to accept that we don’t ever truly get over the fact that there are different paths we could take in life, but that we are finite beings? We choose one, but we can still always see the other options telescoping out, with their endless alternative consequences, on and on into the distance.

Epstein’s ending, when I finally got to it, was just as startling to me as Nicole’s, even though his ultimate disappearance is known from the first page. He vanishes in the end, but I’d like to think that before that, and perhaps after, too, he arrives, filled with the unknown, into something profound.

EF: I’d agree. It’s possible that the reason I found it disturbing is because it’s open-ended. Not to harp on it, but this wider world seems to really afford you a lot of new possibilities. There’s a lot of focus on needing to please the reader and the conflict that can come with that. Does that hold particular fascination, or was it a product of the narrative unfolding the way it did?

NK: Well, for me, unfortunately, when I consider the reader, what I am usually considering is his or her potentially long and urgent list of grievances. Who knows why? A few thousand years of Jewish upbringing, I guess. Of course I write with the hope of the work being received, being understood. But at least while I am writing, the reader is usually someone that I might disappoint, disgruntle, or even enrage. No matter how many readers have apparently loved the books. And so the reader, gentle or otherwise, must be packed off and sent away during the years that I am writing.

When I consider the reader, what I am usually considering is his or her potentially long and urgent list of grievances. Who knows why? A few thousand years of Jewish upbringing, I guess.

EF: You mention menucha as being this idea of infinity, but also maybe imply that it can be a space for God and peace. Coupled with lines — especially in the Nicole narrative — about wanting to drop out of time, I wondered if you were seeking to reach a sense of calm in your prose. If such a state is possible, do you think it would necessarily make for a good place to write from?

NK: One of the things the book asks of us is to be moved and to move — not to stay still. Not to accept that there is only here and there, but that the world is more subtle and more contradictory, and that we can be many things and in many places at once, and therein lies the tension of being. We may understand that both form and formlessness exist, but our desire is for coherence and shape. We subscribe to form and begin subscribing to and trying to uphold it. The problem is that it’s not a perpetual form, and at some point, we have to allow it to break. We have to change our minds and our ways of being, and that requires perpetual work, and an acceptance of some impermanence or instability. But I’m not interested in living in a continuous state of contentment and peace. The hope, as I see it, is to expand our experience of life until it is lived as deeply and authentically as possible, and peace comes and goes in such a life. Though when one reaches the end, I imagine there may be a better chance of peace being the last note.