Books & Culture

Nocturnal Animals: Female Readers, and the Dangers of Page-Turning Thrillers

Amy Adams spends a lot of screen time reading in this filmed adaptation of a thriller

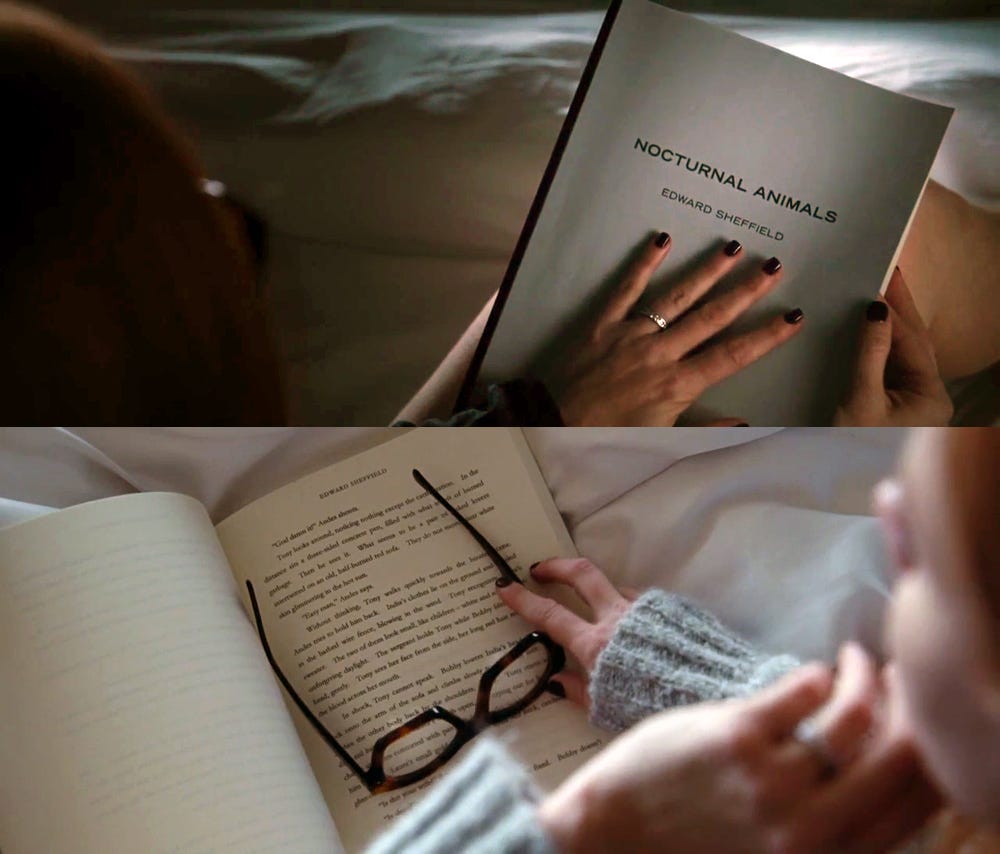

Amy Adams spends most of her time in Nocturnal Animals reading. Her character, Susan, has been sent a galley of a book by her ex-husband, Edward. They haven’t spoken in nineteen years. Not only is the title of his novel a reference to the pet name he had for her when she couldn’t sleep (from which this film gets its name), but it comes with a surprising dedication: “For Susan.”

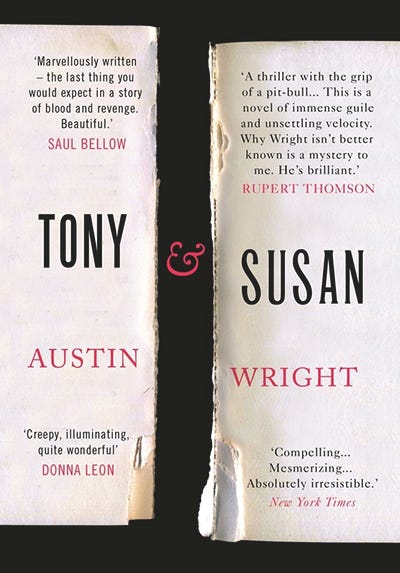

Even more surprising is that it depicts a thinly veiled version of the two of them as a blissful couple on a road trip with their teenaged daughter. Except in Edward’s book, which Susan reads feverishly in her beautiful if cold Los Angeles home, the character of the wife is raped and killed early on, the plot hinging on her husband’s subsequent search for justice. As director Tom Ford writes it in his adapted screenplay, the moment Susan realizes what kind of work her ex-husband has authored, “She is stunned. The deafening silence and the stillness of her bedroom is in sharp contrast to the scene she just read. It takes her a moment to calm down.” A thriller wrapped in a marital revenge drama, Ford’s Nocturnal Animals — like Austin Wright’s Tony and Susan, the novel on which it’s based — is also a film about the imagined female reader.

Edward’s novel, with its titillating violence against women, thrills and terrifies Susan in equal measure — both for what it tells her about her ex-husband (played by Jake Gyllenhaal), as what it reveals to her about herself. To be sure, this is the promise of all great literature: a book, Kafka instructs us, “must be an ice axe to break the sea frozen inside us.” Or, in Proust’s words, “In reality every reader is, while he is reading, the reader of his own self.” But Susan stands as a peculiar avatar for a reader because the book she’s engaged with is particularly designed as a weapon against her. In the book, as in the film, she is cautious about approaching it, preferring to read while she’s alone.

Following the book’s violent opener — which sees Tony (Edward’s alter-ego in his novel, also played by Gyllenhaal in the film) standing helpless as his wife and daughter are abducted by three men on an otherwise empty West Texas highway — Susan begins to worry about what’s yet to come. She recognizes the genre Edward has opted for, and she knows where the story is headed. But since her identification has already been co-opted (she can’t, after all, root against the book’s protagonist, especially when it so clearly feels modeled on her ex-husband, whom she both pities and cares for), she begins to fear that Edward may be laying a trap for her, guiding her thoughts towards places she has gone great lengths to avoid. As in Wright’s novel, the process of reading Edward’s novel leads her to retrace their failed relationship, which among other reasons fractured because she was unable to champion his writing as much as he would have liked.

But there’s a deeper fear here too, one that speaks to the kind of danger a book can conjure for its reader. It is a fear which Wright’s Susan voices in the source novel, stating that “she hopes she’s not being manipulated into some ideology she doesn’t approve.” As a moment of character introspection, this admission is revelatory. Here is a reader all too aware of the way reading can lure you into places you wouldn’t otherwise visit. In Wright’s novel Susan resides in the suburbs, a wife and mother whose picture perfect existence might crumble if she allows Edward’s novel to rattle her. She lives cocooned from outside disturbances, something that Edward’s novel pointedly reminds her. The most fascinating aspect of Wright’s Tony and Susan is the constant frisson between Susan-as-reader and ourselves as readers. The chapter sections that deal with her reactions to the novel come across like a running commentary on the attachment of contemporary audiences to lurid works of fiction. “Tony’s [fictional] world resembled Susan’s except for the violence in its middle,” we are told,

which makes it totally different. What, Susan wonders, do I get from being made to witness such bad luck? Does this novel magnify the difference between Tony’s life and mine, or does it bring us together? Does it threaten or soothe me?

As if to drive the point home, the narrator tells us that these questions “pass through her mind without answers in a pause in her reading.” Wright’s novel is constantly making us aware of these kinds of readerly responses to the text, making us question our own involvement in Tony’s and Susan’s plights, and leading us to wonder whether (and why) reading such violent novels can be both soothing and threatening at the same time.

Edward’s “Nocturnal Animals” is not a far cry from the type of airport paperback thrillers that make it onto book club and bestseller lists, all the while bracketing their own violence as belonging to a fictional elsewhere, one unrelated to the comfortable home where you sit down to read them. Devoid of the inner monologue which Wright offers his character on the page, Ford merely presents us with shots of Adams sighing or looking aside as she sets down the book. There’s anguish in her eyes, giving us the sense that the icy cold woman she is today might be thawing — proof of the humanistic power of the printed word, an art form more earthly and able to connect with real people than the conceptual art she deals in. (It’s no coincidence as well that we frequently see Adams reading at home alone, without the harsh if elegant makeup she dons for work). This change in Susan’s demeanor, Wright and Ford suggest, has to do with being confronted with violence. There’s something in the experience of reading about the indiscriminate violence depicted in Edward’s novel that destabilizes her worldview, and even risks upending it altogether.

In many ways Tony and Susan is a probing commentary on a reader’s imagined safety when dealing with portrayals of violence. “The book weaves around [Susan’s] chair like a web,” we’re told. “She has to make a hole in it to get out. The web damaged, the hole will grow, and when she returns, the web will be gone.” It’s a clear metaphor for entrapment, one which imagines her process of reading as a helpless struggle and pinpoints the feeling of losing oneself in a page-turner, though it recasts it in a wholly sinister light.

If, as recent cognitive scientists suggest, reading fiction makes us more empathetic (and remind us that women are more likely to pick up a book of fiction than men), this figure, of a female reader as a damsel in distress caught in a web of her own making, is particularly illuminating. It not only reimagines the most reviled of readers — those driven by emotions and seemingly easy to manipulate — but specifically maps that other looked-down upon group of readers: women. That the two groups have, historically, been lumped together is not so much a coincidence as a matter of fact. And so, while ideas of empathy and identification, of sentimentality and imagination, are embodied by Susan whenever she picks up Edward’s novel, the male author is shown to wield those concepts as a means of punishing his female protagonist, making a mockery of her own self-indulgent, empathetic reading experience.

In the big screen translation, Ford further complicates this tension. The suburban reader who lives vicariously through pulpy novels, providing her a sense of danger from the comfort of her picket-fenced home, has been transposed onto a vacuous coastal elite who lives an empty life and has no contact with what’s “real” — here, quite literally, and in a Trumpian sort of way, geographically in the South. In this new iteration, Susan is an art dealer whose gallery show opens the film: naked obese women dance in slow motion on giant screens to the delight of a gawking, Angeleno crowd. Everyone tells her it’s a success. She thinks it’s just junk. Overall, the dirty and gory reality that Edward offers her in his book, about laconic detectives and chauvinist criminals, becomes all the more striking. The contrast is made salient thanks to the film’s visual style, as Ford takes the sterile world of Susan’s Los Angeles — with its minimalist design and monochromatic palette — and juxtaposes it with the grimy, dust-covered world of West Texas, which feels oversaturated in comparison.

In the film’s final scene, Adams’ Susan sits and scans around the restaurant where she’s supposed to meet Edward. A few drinks later she realizes he’s not coming. Ford cuts to black before we’re allowed to see what she will do with the understanding that this has been, among other things, a cruel joke at her expense. The empathy she has expended on the novel — and which Ford visualizes with the golden cross that Susan often fondles as she reads, and which we see Tony wearing in the film’s in-book sections — is diminished as meaningless, as hollow as anything adorning her expensive house, as aimless as the cars littering the many establishing shots of the Los Angeles cityscape that punctuate the film. She’s been manipulated, playing right into Tony’s game, caring too much for his characters and his new career only to have that sentiment mocked and dismissed.

That the film ends on such a nihilistic (and torturous) note makes apparent the gendered dynamic that Wright had already embedded in his metafictional page-turner. “If Edward couldn’t live without writing,” Susan “couldn’t live without reading.” In other words, man writes, woman reads. In Nocturnal Animals, which is eager to ogle and revere its male characters and quite happy to make Susan a prop on which to hang the misogyny and elitism she begrudgingly exults, this simple proposition leaves an unsavory aftertaste. Whatever irony there was in Wright’s prose has gone. What’s left is a disdain for the type of reader Susan represents, the type of audience we ourselves have been nudged to become. And like Edward, Ford ultimately gets the last laugh, leading us on in expectation without ever showing up.