Books & Culture

Nonsense, Cartoons, and My Post-Soviet Adolescence

I was shaped by the rigid truths of Soviet cartoons. Then I discovered “Alice in Wonderland”.

The hero of the first book I ever read on my own, Dr. Aybolit (literally translated, “Dr. Damn it hurts!”), was a straightforward figure who could cure everyone and everything. It didn’t happen to matter if you were a crocodile or a bandit, his remedies — which sometimes tasted like chocolate, other times like Leningrad spice cakes — would nurse you back to your feet in no time. I still attribute my present-day iron persistence to the effect of Dr. Aybolit on my early stages of development. As it is with anyone, the stories and images of my childhood came to form the foundations of how I assumed things must be.

I was a rather smart little girl once. According to one folk theory my intelligence came as a result of my rebelliously curly hair, which resembled an explosion beneath a pasta factory. As an adult I straighten my hair ruthlessly, which probably accounts for my somewhat lowered IQ. The fact is, the type of theories I prefer these days have little to do with logical relational connections, and much more to do with nonsense. I instruct my friends about the effect of moon phases on the rates of petty crimes. I blow smoke into their pensive faces, declaring that only people statistically likely to die from lung cancer are inclined to actually start smoking, and so they have little to worry about. I routinely mock my economist friends’ first premise about humanity, which is that people are essentially rational. It’s a wonder that I have any comrades left.

But how did this come to be, you might ask? I certainly do. What would cause me to abandon a childhood of storybook sense, to champion instead the anarchism of absurdity and nonsense?

I was not only a smart, rational little girl once, but cultured too. When my mom took me to see a play concerning the adventures of a worldly lion, who eventually returns home by the time the velvet curtains fall, I summarized it for her afterwards with a single, pithy line: “Only by leaving home can you find out where it is.”

Perfectly logical. Of course, I was accustomed by then to the idea that the point of stories was to teach me how to be. Take for instance this tale, of an unhygienic little boy who is punished by what else but an enormous sink come alive:

Phantasmagoric as the situation might be, the moral itself is perfectly clear, and naturally involves a good deal of soap. As a voracious cartoon junkie in the early 90s — just as Soviet animation was ironically coming into wider consumption, with the growing availability of televisions now that the Soviet era had ended — I became, without knowing it, a five-year-old critic of Russian Formalism, a school of literary thought that looked on works of art as independent of their cultural or historical background. Had I possessed the vocabulary back then it’s possible that I might have joined Trotsky in advocating for the contextualization of social and psychological reality in cartoon form. Which is to say that all my favorite animated films at the time were rooted in sobering and unglamorous reality:

Apparently, my favorite childhood cartoon involved a manic, suicidal chain-smoking screenwriter; a pill-abusing film director; endless bureaucratic delays; the most obnoxious girl actress in the animated world; and a finale in which the entire crew weeps over their reward, a scrawny and unsightly bouquet. Once again the intended message is clear: filmmaking, as with much else in life, is a great deal of hard work in return for the superficial prize of fleeting applause––the real value lies in the work itself. In other words: do the work, but don’t seek prizes.

This was hardly the only moral lesson to be found in Soviet cartoons. Here is little Antoshka, whose adamant refusal to join with the other child laborers as they dig for potatoes predictably results in feelings of starvation and regret:

Or the lazy blonde-haired student and his cat, magically transferred to the Country of Unlearnt Lessons, where he comes to learn the value of work:

Or perhaps this hippopotamus, who in preferring not to get properly vaccinated ends up with jaundice:

Or, on a marginally brighter note, a domesticated feline and a hunting dog from Prostokvashino, who mutually learn the value of sacrifice and friendship after sharing a household:

Obedient to the dogma, I believed myself to be a model elementary school kid, sharing crayons with those friends of mine in possession of less notable crayon collections. My perspective radically changed on the day that my grandfather, a natural contrarian––anti-USSR during the time of the union and pro-USSR after it fell — fatefully told me to turn off the television. In its absence I discovered Alice in Wonderland.

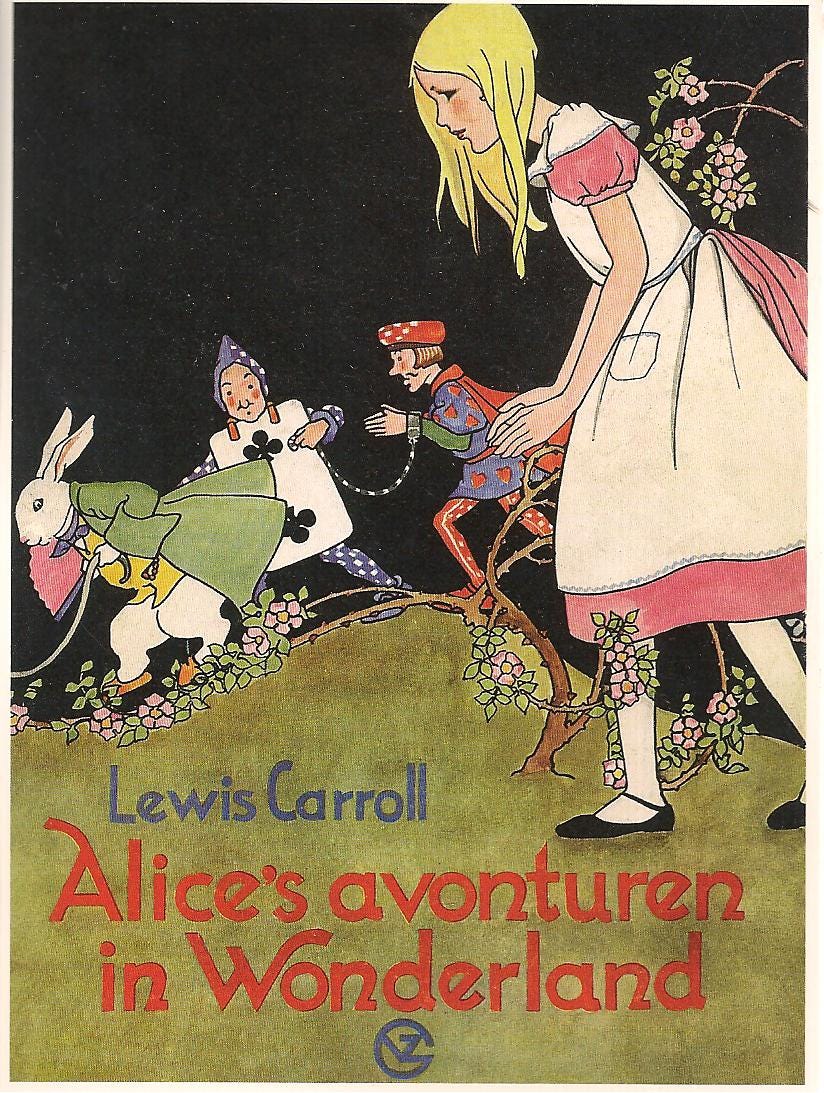

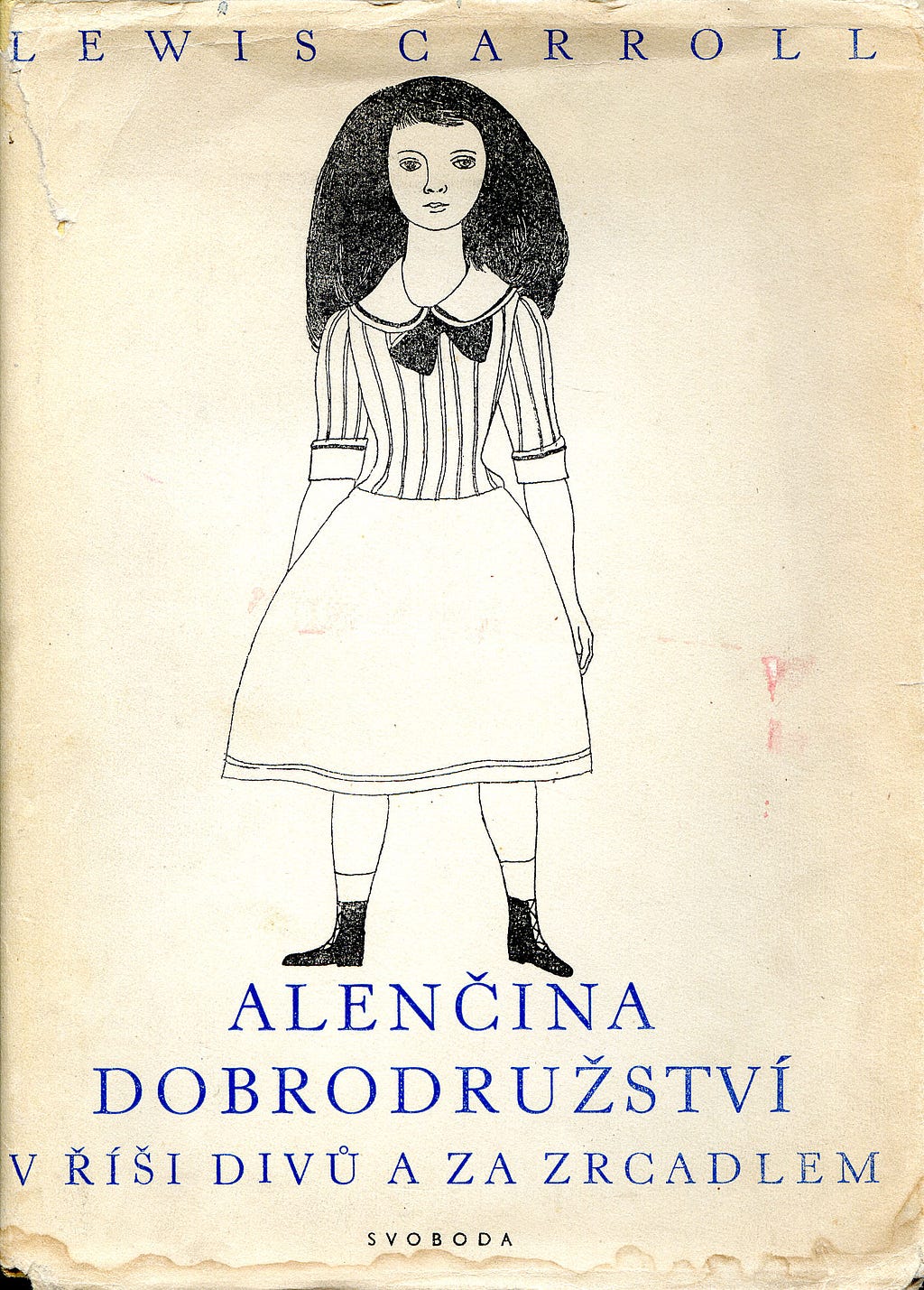

My grandmother’s room had always been, for me, a passage to strange realms. Dimly illuminated and with a distinct smell of perfume gone bad, it allowed me to imagine, when I wrapped myself up in her enchanting shawls, that I was a Parisian dancer, or a goddess of various different seasons. On that particular day it was a book on her nightstand, rather than a piece of ancient jewelry, which produced a transportive effect. When I finally emerged from binge-reading Lewis Carroll’s story it was as if no time had passed. What weighed on me after––what inscribed itself into me and made that book my favorite from then on––was how drastically different the tale was from what I regularly encountered in the Soviet cartoons. Unlike with their insistence on rationalism and logic, the confusion of my looming adolescence made much more sense alongside the book’s thrilling absurdism.

Alice in Guantánamo: Reading Carroll in the Gitmo Age

According to my parents, in the world they had grown up in––the world reflected in the cartoons––there was little room for uncertainty or anxiety. Almost everyone was employed and everyone had enough money (although if anything was lacking it was having sufficient ways to spend it). Women hardly gave a thought to their careers, encouraged to find more meaning in family. Everyone respected collared workers and professors, and looked down on those who made their living importing, reselling, or representing products. The “hustlers”––those who somehow else got by (scornfully called “speculators”)––were figures of especially low regard.

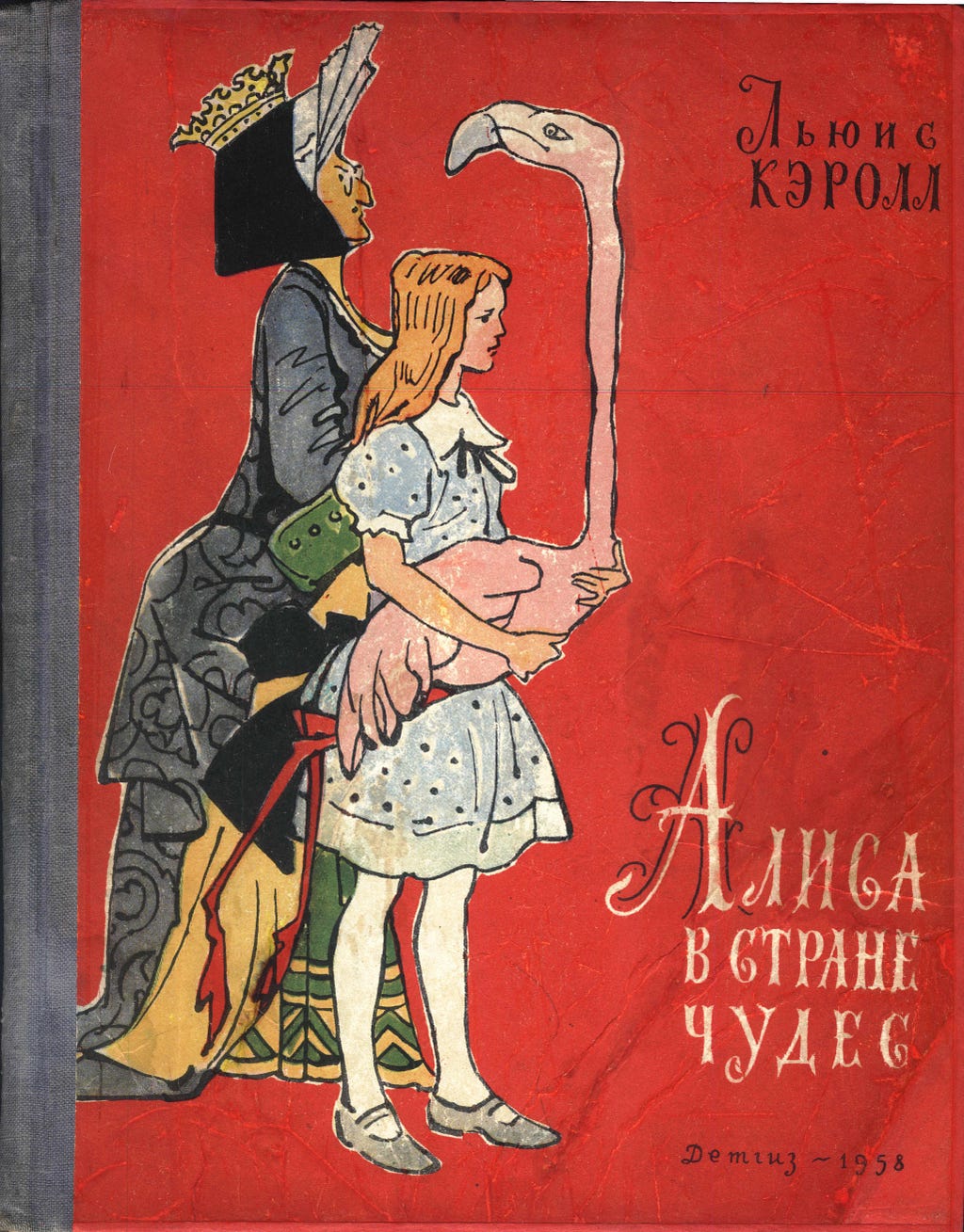

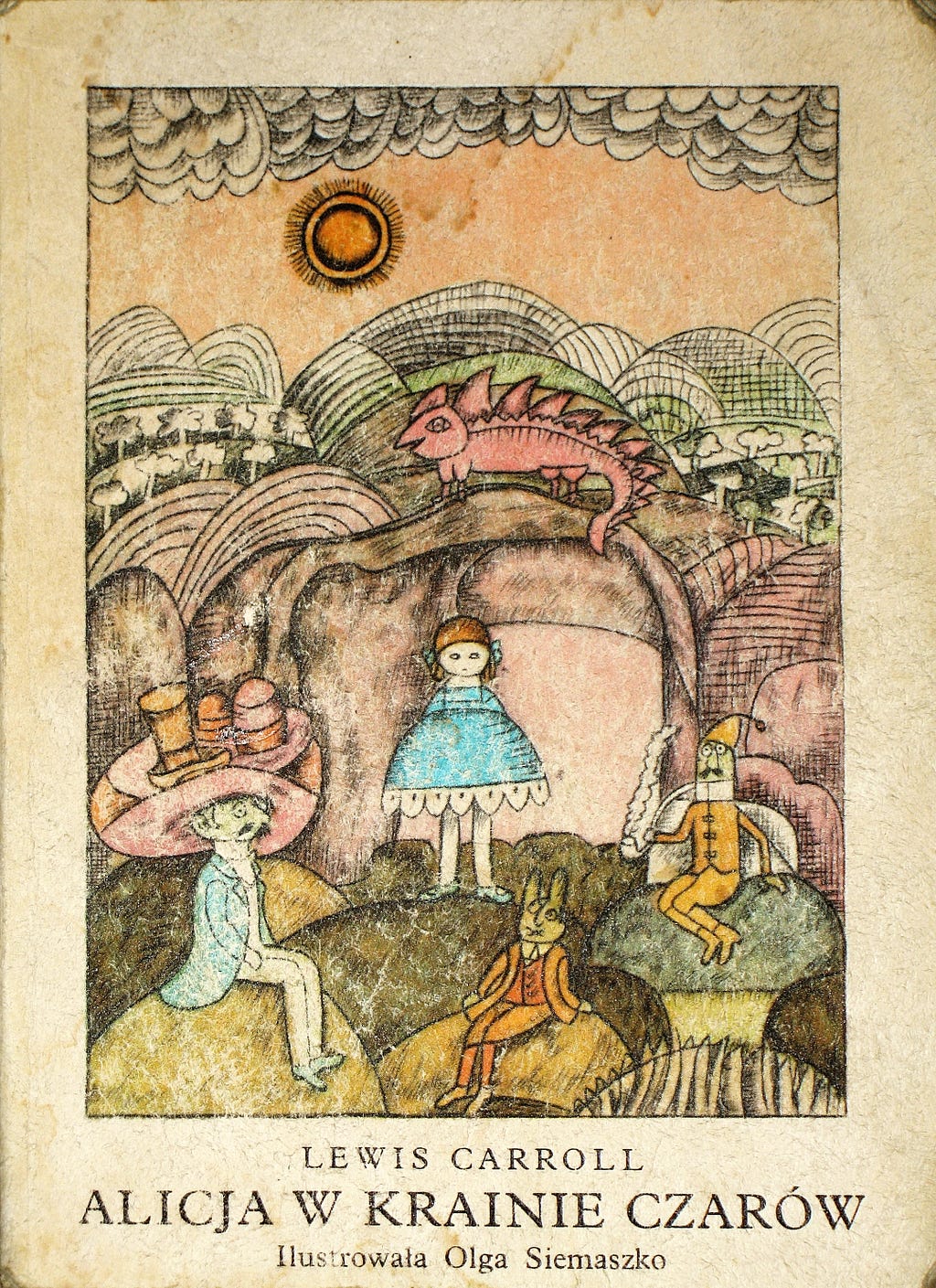

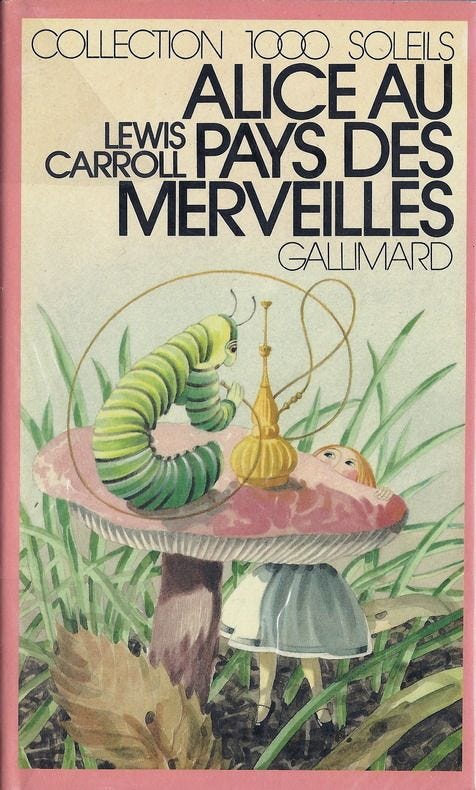

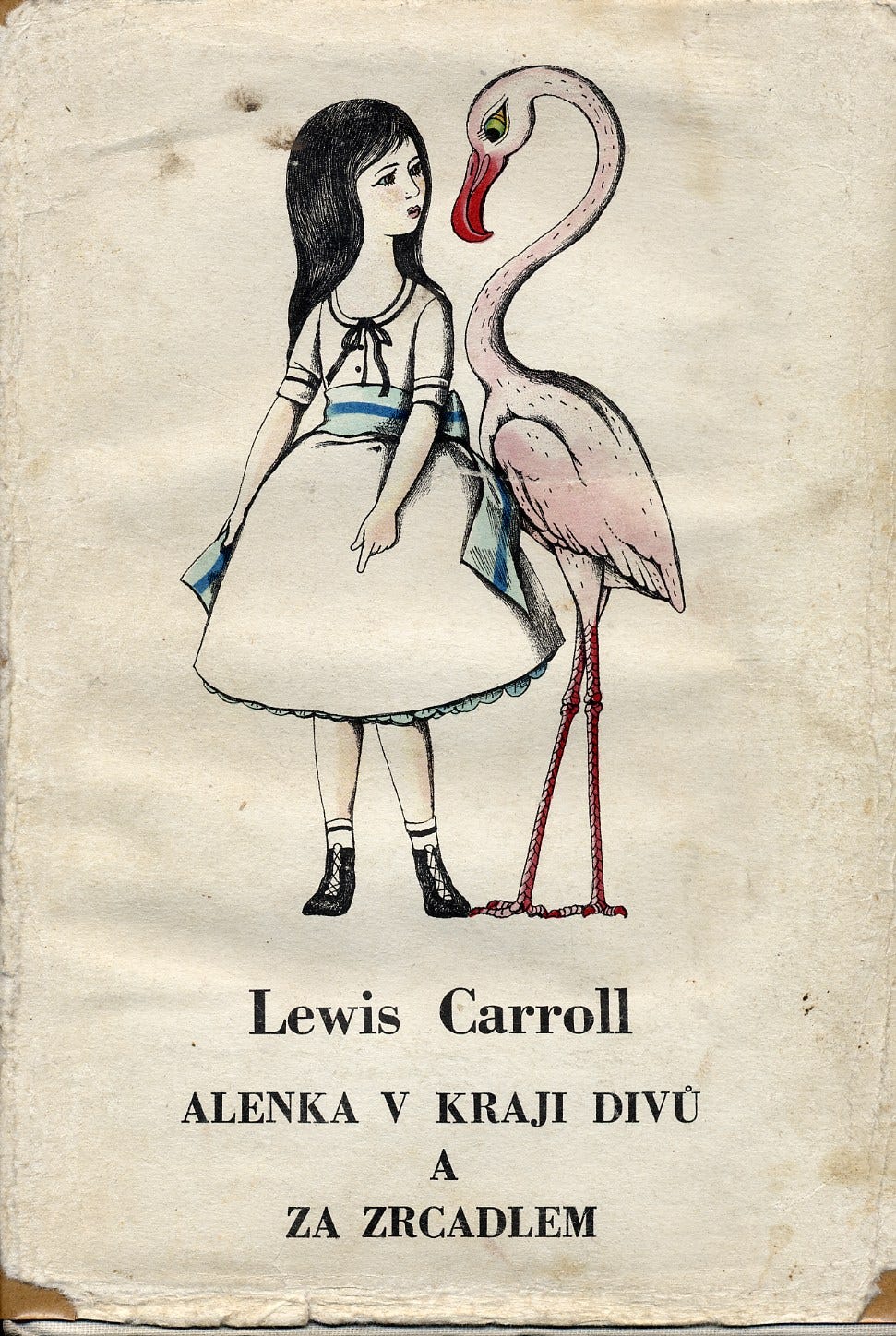

Cover Gallery — Alice Around the World:

So it was to my great shock and comfort when I read that book to find that Alice chooses the White Rabbit, the deviation. She has no noble quest to fulfill, seeks neither tender reunion nor exemplary friendship, and finds nothing to praise in the idea of societal order (especially as presented by the monarchy of the King and Queen of Hearts). In a world that seems topsy-turvy, she swiftly adapts. Otherwise, she relinquishes control: as she says to the Dormouse, she can’t stop herself from growing up.

By contrast there was nothing altogether wrong with my Soviet cartoons, only that they came too late, trying to prepare me for a world which no longer existed. Hand-drawn and stylistically lovely they told of an anachronistically slow-paced and easily digestible life, a life that didn’t particularly resemble mine––and perhaps not anyone’s. As I eventually grew older and came to the decisions that would determine my path through — such as where and what to study, who to befriend and who to become — Alice was the perfect companion, making no promises about the effects of any of life’s potions.

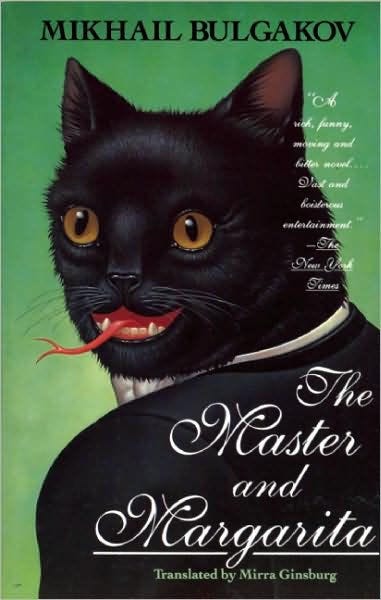

Years after Alice in Wonderland I came to fall in love with Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, a surreal Moscow tale about censorship, self-sacrificial love, and diabolical parties in the urban underbelly, which had been banned by the Soviet authorities during the author’s lifetime. Bulgakov’s novel caused me to think about nonsense not just as an absence of sense, but as a call for sense and order’s abnegation — a call only allowed under systems that make room for nonsense and uncertainty in the upbringing of its citizens. The Soviet system was very particular in the role it assigned to art, to both define and enforce social functioning. It was an irony that in the case of the cartoons the message reached its intended audience too late, arriving only after the onset of capitalism, to indoctrinate impressionable young minds with outdated, ill-fitting ideas. Thankfully for me, Alice came to the rescue––and just in time––offering an assurance that nothing in the world makes sense, so long as you let it.