news

Notes on James Salter’s LIGHT YEARS

Alas the glory of the prince! How the time has gone,

vanished under night’s helm, as if it never were!

From “The Wanderer,” 6th century English poem

He heard the clack of his dog’s old nails on the floor. Hadji sat at his feet, looking up, hungry like all the aged. His dog that had run in the breathless snow, strong legged, young, his ears back, his keen glances, his pure smell. A life that passed in an instant.

From Light Years (1975)

Some things that are plentiful in James Salter’s writing: wartime heroism, the valorization of the dead, striking or farfetched similes, fine things and physical beauty, descriptions of food and drink, sexual opportunism, an almost mystical attitude towards the acquisition of fame and money, accidents, lost youth, sadness at the passage of time.

Some things that are noticeable by their absence: sexual restraint and fidelity, long passages of background or expository prose, politics, humility, Middle America, justice, a sense of damnation or sin as opposed to a sense of time wasted.

In 1992, when he was in his sixties, Salter published an essay in Esquire celebrating the pairing of beautiful younger women with older, powerful men. He made approving references to Abelard and Heloise, to Picasso’s romantic life, to the habits of the Continental nobility, even to sex tourism: “happiness is often at its most intense when it is based on inequality, and one of the imperishable visions if it is of life among a burnished, graceful people not as advanced as we” (by ‘burnished,’ Salter of course means dark-skinned).

Salter is everywhere referred to as a ‘writer’s writer,’ or a ‘stylist.’

Le style c’est l’homme, Buffon wrote in the 18th century. Style is the man. Yet to call a writer a stylist in our day means to concentrate on the surface beauty of his prose and to ignore the man behind the style.

A stylist is often a euphemist of genius, a writer who gives elegant or poetic expression to man’s basest motives or actions. Like Hemingway, Salter is a writer driven not by religion or even ethics as much as by a code, or manners. The code Salter articulates–the code behind the style–is a pagan or aristocratic one, though Salter himself is no blue-blood (actual aristocrats are too complacent, incurious and suspicious of mere verbal glibness to ever expand upon the meaning of their beliefs). Like ‘grace under pressure,’ it is as much about looking good as doing the right thing.

Light Years, like Anna Karenina, is a marriage novel, though without a Kitty and a Levin; it is written from the perspective not of Tolstoy but of Vronsky, from the perspective of a man who values surfaces above all things, whose unhappiness is bone-deep, yet who is closed to alternatives.. The world of Viri and Nedra is the world of upper-middle class New York and Long Island from the late Fifties to the early Seventies. Viri is an architect; Nedra doesn’t work; they give dinner parties, have affairs; shop; divorce; they and their friends grow older and frailer; Nedra dies of cancer.

Nedra, like Rochester or Gatsby, is at the beginning of the novel a mysterious character whose mystery is described largely by her effect on other people. The source of the mystery, the reader realizes with a sinking heart, is something as ordinary as glamour — a numinous-seeming confidence that comes from the envied combination of beauty, money, leisure, and good taste.

Salter is a writer who has cut a figure in the world, been in the thick of battle, spent time in Hollywood, loved many women. The terse Hemingway style is an obvious model for him–the Hemingway of The Sun Also Rises in Salter’s early war novels, the Hemingway of sitting around in cafes and noticing the light on leaves in Salter’s later novels; but his prose has a compressed lushness all its own.

Salter’s prose invites us, through a kind of intensified seeing, to make a grail of laughter of an empty ashcan, in Hart Crane’s words. This promise to transform the workaday world into a kind of magic play land is the promise of the great stylists — Nabokov, Proust, Nicholson Baker.

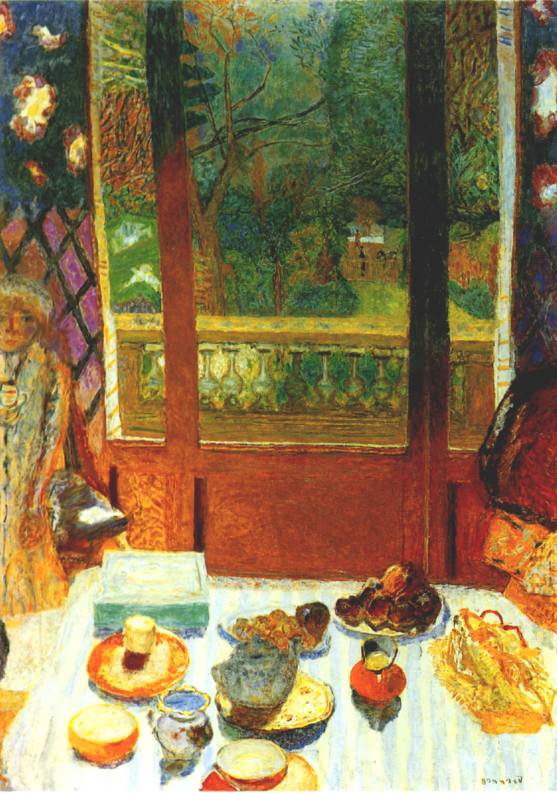

It is also the promise of advertising. Salter, aristocratic hedonist that he is, celebrates a life devoted to the pursuit of pleasure: dinner parties, tailored clothes, lazy alcohol-drenched summers at the beach, gallery-hopping, adultery. But Light Years is no brightly colored advertisement for joie de vivre, no Renoir painting or New Yorker cover: the truth-teller within the novelist, the truth teller that squats within any worthwhile artist, can’t help but describe the heavy pagan sadness that dogs the pursuit of pleasure’s every step; yet the stylist within the artist can’t help glamorizing not just the pleasure but the sadness.

The result is, surprisingly, not an incoherent work of fiction but a tensely satisfying one, one of those rare novels that, in a process like seduction, moves the reader almost against his will.

Why is this book, which elevates the meretricious, the snobbish, the narrowly bourgeois, so moving?

In the pagan consciousness, one of the feelings that approximate religious awe is a sense of the majesty of time’s passing. In Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of Britain, a work in which the pagan overlaps the Christian worldview, a speaker compares our life on earth to the flight of a sparrow through a banquet hall. In Light Years, time is, to use a Salteresque simile, like the ancient stone floor beneath a throw rug.

(What is the true nature of time? Nabokov compared our trying to figure it out — us, sentient creatures living in time — to a harried driver keeping an eye on the road and one hand on the steering wheel, while with the other hand fumbling through the contents of the glove compartment.)

Time, we see, has a dual nature: it is both motion and accumulation; current and sediment. Salter records the movement of the light throughout the day; the changing of the light through the seasons. He records the passage of the years and their cumulative effect, which is to induce a kind of vertigo in man, a wonderment:

There is the dock, unused now, with its flaking paint and rotten boards, its underpilings drenched in green.

[…]

It happens in an instant. It is all one long day, one endless afternoon, friends leave, we stand on the shore.

The heavy sense of the dual nature of time in Light Years makes time itself the agent of drama and gives this mostly eventless and drama-free novel its narrative pull. Salter describes a minor character, a failed painter, as seen through the eyes of his daughter:

He had spent a lot of time with her when she was a child. She remembered some of it. She had lived in waves of color he had chosen, irradiated by them as by the sun. She had seen his torn sketchbooks on the floor with footprints across their pages, she had found him sprawled drunk in her room, his face on the thick spruce boards. She could never betray him: it was unthinkable, He asked nothing of her. All these years he had been beaten, as if in a street fight, before her eyes.

* * *

John Broening’s Column Note.

— John Broening is a chef and writer based in Denver, Colorado. His work has appeared in the Baltimore Sun, the Baltimore City Paper, Gastronomica, Edible Front Range, and the Denver Post, for whom he writes a weekly column about food.