interviews

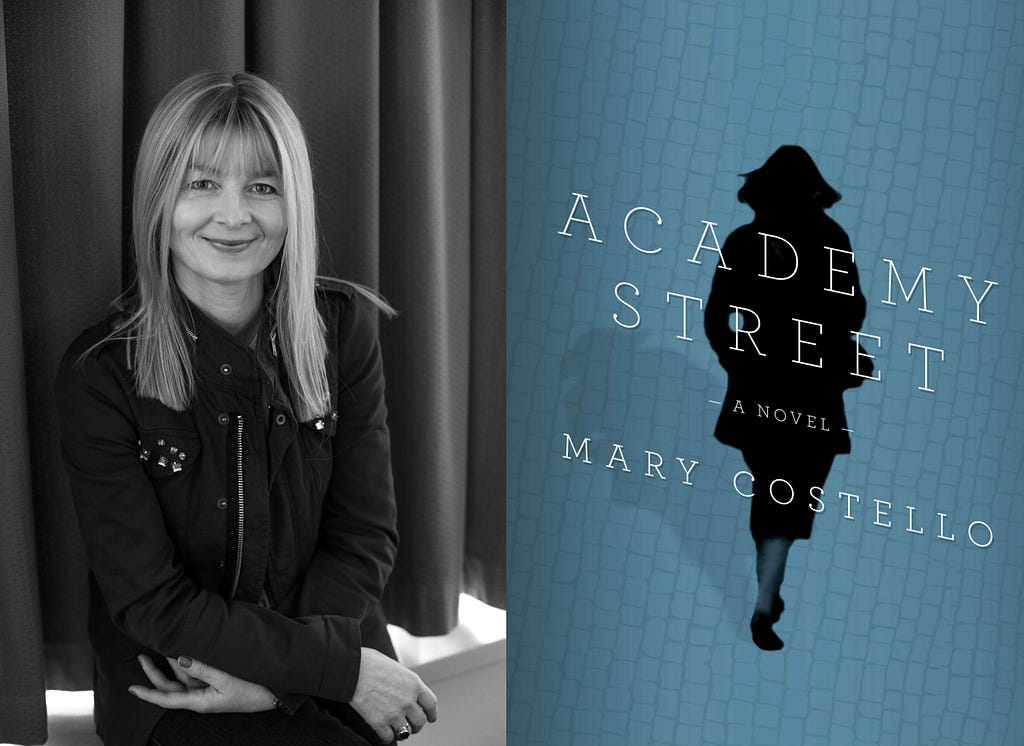

Occasional Glimpses of the Sublime, a conversation with Mary Costello, author of Academy Street

by Johanna Lane

Earlier this month, Mary Costello’s debut novel, Academy Street — winner of the Best Novel Prize at the 2014 Irish Book Awards — was released in the US. Academy Street is a portrait of Tess Lohan, a single mother come from Ireland to forge a life in New York. We asked Johanna Lane — who moved from Ireland to New York in 2001, and whose own debut novel, Black Lake, will be released in paperback on May 5th — to talk with Costello for Electric Literature. They discussed emigration, the Irish in New York, J.M. Coetzee, and the different demands of a short story and a novel.

Johanna Lane: I love the work of J.M. Coetzee and in my mind you and he are closely aligned. Not only do you share the last name of one of his characters, Elizabeth Costello, but you mention another, Michael K, in your novel, Academy Street. Some of his novels are elliptical, as is yours, which was one of my favorite things about it, but another writer might have chosen to tell the story of Tess’s life in 500+ pages. You took less than 150; why?

Mary Costello: Thank you, Johanna. Coetzee is one of my favourite writers, so this a great compliment. It’s the integrity of his work that so impresses — the sensitivity, the refined feeling, the constant endeavour to imagine the lives of others, human and non-human. The way his characters cogitate on life and death, suffering, salvation…and are unafraid to face awkward truths. With Coetzee there’s no escape from the self. And yes, the coincidence of the Costello surname sort of floored me when I first came on it!

I never set out to write a short novel — I thought Academy Street would be longer. I wrote it in a fairly linear fashion over one year, although it had been incubating for several. I found Tess’s voice early on, and tried to keep tight to it. She dictated the tone and pace and duration and led me across those bridges from one period of her life into the next without too much fuss or detail. She’s an introvert — an intuitive introvert — so things don’t need to be spelt out or laboured over; they can be gleaned.

I’ve always written short stories — my first book was a collection of stories — so I’m probably naturally inclined towards brevity. Plus, when I speak I have an almost pathological fear of boring people and this might, unconsciously, have a bearing on the writing too. The writing self won’t tolerate loquaciousness!

JL: I was having dinner with another writer the other night and we were discussing tone. I find that I very often forget what happened in books, but I remember the tone of novels I read ten or more years ago. Speaking of Coetzee, though I haven’t read In the Heart of the Country in a very long time, its tone still settles on me now when I think of the book- the same goes for Waiting for the Barbarians. You mentioned in your last answer that Tess dictated the tone of Academy Street; how do you understand the concept of tone? How does it affect your work and your response to the work of others?

MC: I think of tone as a kind of force field around the character that has agency over the narrative. I find it difficult to talk about tone without referring to character and voice. In the case of Tess, there’s an air of quiet trepidation attached to the way she lives. I had to convey this trepidation, this quietude, in language that is apt for her. The way she thinks and moves and has her being needed to be reflected in the language and syntax — and in the point of view, too. Without ever deciding, I employed close third person point-of-view, so the tone that emerged is intimate.

Getting the tone right is very important. It’s not something that can be forced or rushed — it seems to come almost involuntarily. And it can be easily lost too. At times during the writing of the novel I felt it slipping and I grew very anxious. But there was nothing to be done — except step away and wait. Without the right tone, the writing always feels false.

You mention In the Heart of the Country and how the tone still settles on you. I find that most of Coetzee’s books cause a pall to descend — and just the thought or the sight of them can evoke this feeling. Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams has that effect on me too. And speaking of palls, Marilyn Robinson’s novel Housekeeping comes to mind. The tone is delicate, elegiac, conveying the ethereal quality of Ruthie and Sylvia. And alongside this delicate tone is an atmosphere of endangerment and doom that’s felt by the reader in the very act of reading the book.

JL: How does being Irish shape your fiction, either in terms of form or content, or both?

MC: There’s no doubt that being Irish has a huge bearing on how and what I write, just as being Canadian or American has a bearing on what Alice Munro or Marilynne Robinson write. Ireland is where I landed on earth, and so it’s part of my literary landscape and heritage through story, myth, song, poetry — it’s in my DNA. The particular rhythm and cadence of the language as it’s spoken here is present, so my writing voice is Irish. How could it not be? But I don’t intentionally write about Ireland or Irishness — it’s just there, natural, not something I’m conscious of or that needs to be inserted.

As regards content, I write about love, loss, death, fate, men and women, the interior life — subjects common to all nationalities. The settings and the outer landscapes of my characters’ lives are mostly Irish — though most of Academy Street unfolds in New York — but these matter less to me than their inner landscapes — what Robert Musil called ‘the floating life within.’

I don’t think being Irish has a huge bearing on the form I choose to write in. I started writing stories in my early twenties because I had lots of isolated characters and disparate images and ideas and the short story was a form that could accommodate them. I’ve written stories for years but then the reach of Tess’s life in Academy Street needed a longer form. The Irish have a great reputation for short stories — the Irish short story travels well — and it was the Irish writer Frank O’Connor famously coined the term ‘the lonely voice’ to describe what is essential in a short story… that ‘intense awareness of human loneliness’. And the short story is particularly suited to depicting isolation, melancholia. But loneliness and isolation are universal and short story writers from all over the world, not just Ireland, do these very well.

JL: What’s the most difficult aspect of the writing life for you?

MC: Fear, self-doubt, anxiety that I won’t be able to realise the characters and the story as I ‘hear’ them. Holding my nerve. Finding the exact words — which is usually impossible. Finding the voice, too. I feel great relief and gratitude when I find the voice — though of course it can be difficult to hold onto.

JL: Can you tell us a little of how you came to writing?

MC: Writing was never on my radar when I was growing up — I never dreamt of being a writer. I grew up in the west of Ireland and came to college in Dublin when I was 17. I studied English and was always a reader. When I was 22 something began to gnaw, something I couldn’t put my finger on. During a period of insomnia the thought just dropped down me out of the blue one night: I want to write. I have no idea where that came from. My first two stories were published, one of which was shortlisted for a well-known Irish prize, the Hennessy award.

I’d gotten married when I was 23 and moved to the suburbs, and I was teaching fulltime. Then somehow, writing began to slip to the margins of my life — I couldn’t seem to accommodate everything. I wasn’t part of any writing community either. Writing felt like a burden, a secret, an interruption to life, and I tried to give it up — six months or more would go by when I wouldn’t write. But it never went away entirely. Stories would push up and plague me until I had to write them.

My marriage broke up after ten years and I continued to scribble away. And then in 2010 — I was well into my forties by then– I sent two stories to a literary magazine called The Stinging Fly here in Dublin. The editor liked them and published them and asked if I had more. And I had, and he wanted to publish them — he runs a publishing house — which is how my collection, The China Factory, came about.

JL: You’ve worked successfully in the short story form and in the novel form; what are the different demands they make on you as a writer?

MC: For me, the challenge in both forms is to keep the story in the air; find the precise language, the right voice. I’ve written stories for longer and I’ve a great love for the form — its claustrophobic feeling, its intensity. There’s an intuitive quality to stories and less transparency — something always lurks beneath the surface.

Pacing is different in a novel, obviously, and one needs to be more patient. But there’s more breathing space. When I was writing my novel I wrote each chapter in much the same way as I’d write a story. I didn’t write one draft straight through– I wrote each chapter and then rewrote it many times before moving on. I didn’t think long-term… I edged my way forward.

So, in many ways the same demands exist in both forms — the need to keep the thing taut and the language exacting. I can’t say if one is more demanding than the other… A story has to be kept it in the air for maybe 20 or 30 pages and novel for 200–300 pages, so one has to hold one’s nerve for longer with a novel!

JL: I teach in the neighborhood Tess first lives in, Washington Heights; how did you evoke a city, a country, you’ve never lived in so convincingly?

MC: Two of my mother’s sisters and a brother emigrated to New York in the late 1950s and early 60’s. One of her sisters, Carmel, was a nurse in New York and lived in an apartment on Academy Street in Inwood at the northern end of Manhattan. She worked in the New York Presbyterian Hospital for four years before returning and settling back in Galway. When I was growing up she told me stories — and still does — and I got a real sense of her life and times in New York.

I’ve always been in thrall to New York — I grew up on American TV, film, music. Also, we got photographs of aunts, uncles, cousins from America that I pored over as a child, all of them looking more beautiful than my Irish family! And I thought: this is what America does, it makes people beautiful. As you say, I’ve never lived in New York but have visited many times. I was there in the summer of 2011 and I used to take the A train up to 207th Street in Inwood, the last stop. I found Academy Street and the apartment building where my aunt had lived. I walked around the streets and the park, visited the church, the library; imagining the lives of my aunts, my uncle; hearing the echoes of their footsteps on the streets, the footsteps of so many Irish emigrants who’d lived there. There is something about that generation of young men and women — their innocence and earnestness, their lack of cynicism too — that moves me. One day I sat on a bench across the street from the school as parents gathered to collect their children. I could see the little heads of the children in an upstairs classroom, and tiny hands being raised and lowered. In that moment Tess’s whole life seemed to unfold before me.

JL: Why do you think the story of the unwed, single Irish mother continues to capture our imagination at a time when it’s no longer taboo- or certainly no longer as taboo as it once was?

MC: I think any human suffering — especially one caused by intolerance and prejudice — strikes a chord with people.

And it’s not that long ago that single motherhood carried a great stigma in Ireland and was regarded as a mark of shame and disgrace for families — such prejudices pertained right through the 70’s and even the 80’s. Of course this wasn’t unique to Ireland but it persisted for longer here, and in the last two decades we’ve heard the stories and testimonies of those who suffered — sometimes wanton cruelty — at the hands of church and state institutions and women’s own families too. So many lives were ruptured and the victims are still enduring the great emotional and psychic pain. Those were dark times … I think there might be some feeling of collective guilt in Irish society now — at any rate there has been a much greater readiness to face the past and give voice to the voiceless.

JL: What do you think Tess’s life would have been like if she’d never emigrated?

MC: I imagine she’d have continued nursing in Dublin, maybe gotten married, had a family. One thing is fairly certain — if she’d had a child outside marriage she would’ve had to give him/her up for adoption.

Would she have fared better, been happier, suffered less if she’d stayed in Ireland? Who knows? Tess is an introvert by nature and would always have found it difficult to mediate the outer world. I think, too, she would always have had some inner longing, some ache for ‘home’ — a metaphysical home, that eternal longing to put her finger on something sublime or numinous. I’m not sure she’d have discovered her love of books as she did in New York — which of course helped sublimate many of her anxieties and gave her occasional glimpses of the sublime.

JL: As an Irish writer, did you have any hesitation about “owning” major events in US history, like the Kennedy assassination and 9/11?

MC: I don’t think the imagination recognises international borders. Altering or tamping down a story or doing anything that compromises its integrity would be a form of self-censorship and isn’t something I could do. When I’m writing, I don’t think about a reader or my agent or my publisher. My only concern, my only allegiance, is to my story and my characters. I know this is a broad and complex issue, but, in the actual writing, a writer can only do what he/she sees fit and abide by their own conscience and the needs of their stories.

The global shock and outpouring of grief at those signature events — like JFK’s assassination and 9/11 — is natural in the face of such human loss. But there’s also the fact that America is a nation of world nationalities so we all feel, to some extent, that they are our losses too. Then there’s the strong Irish connection through emigration, which is felt as familial for many. My mother can point to the exact spot in the kitchen where she was standing as a young woman when the news came on the radio of Kennedy’s death. A national day of mourning was held in Ireland on the Friday after 9/11 and businesses shut down and people who’d never set foot inside a church in their lives went to memorial Masses and services to honour the dead and share in the grief. These tragedies left their imprint on our national psyche too. Years after 9/11, I accidentally discovered that a distant cousin died in the Twin Towers. The knowledge that a blood relative of mine had perished that day had a profound effect on me and brought that catastrophe closer, forced me to relate to it in an even more personal way.