Books & Culture

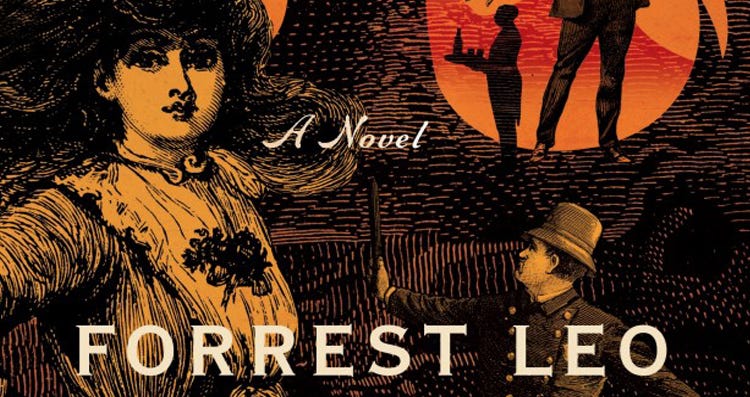

On Accidentally Selling Your Spouse to the Devil

Forrest Leo’s debut is a rollicking romance through Victorian London

“Lost are we, and are only so far punished,” Dante writes in Canto IV of the first part of his epic poem The Divine Comedy, “That without hope we live on in desire.”

In his debut novel The Gentleman, Forrest Leo crafts a story that hinges on these Dantean elements of confusion, punishment, and romantic longing. Lionel Savage, the narrator and protagonist, accidentally sells his wife Vivien to the devil and embarks on a strange and comical journey through Victorian London to get her back. He relays his trials and travels in the form of a memoir, executed and edited by Hubert Lancaster (a cousin of Savage’s missing wife), who provides footnoted commentary throughout.

“Leo has a whimsical gift: he has given Dante a key place in The Gentleman — as Satan’s gardener.”

Such double-sided narration — through both Savage’s first-hand account and Hubert’s numerous annotations — wedges a kind of distraction into the story, as the two voices often diverge. “Lost are we” comes to mind as an adequate description of the readers’ (and characters’) experiences. And in Dante’s world, being lost means being deeply susceptible to waywardness and despair. Romantic desire becomes unquestionable, as it does for Savage: his one ungovernable aspect, untouchable by the instruments of hell. Dante wields an uncanny ability to characterize and represent change as it manifests in people. Leo, presumably a long-time student of Dante, knows this better than anyone. He employs Dante’s same sense of mutability and unpredictability. And like his predecessor, Leo has a whimsical gift: he has given Dante a key place in The Gentleman — as Satan’s gardener.

One of the novel’s prevailing questions is what makes a man a gentleman, as Hubert suggests at the beginning that it is for the reader to decide whether “Mr. Savage is deserving of that epithet.” The clearest and most helpful definition emerges from Dante’s own writing, in which he argues that a gentleman must have an abito eligente, an elective habit, which compels him to make the reasoned choice, the choice of the mean between two extremes. Steady temperament, then, makes a gentleman.

Leo’s play on this definition is one of many great ironies. Lionel Savage, his young poet hero, is anything but steady. In fact, in the epigraph that opens the book, Savage admits that he drinks his tea “in one great gulp” and casts about with a “griping eye.” He is indulgent, he brags about his fame, and, above all, he uses “thirst” as a directive. In many ways, Leo’s opposing idea of a gentleman speaks to his carefulness as a reader, for Dante also writes that the gentleman is a man whose “soul” must “grace adorn” and “in itself enjoy.” This underlying Epicurean sense — that the truly happy and noble man enjoys his being and is not, in essence, beholden to temperateness — is what Leo takes and makes his own.

“In many ways, Leo’s opposing idea of a gentleman speaks to his carefulness as a reader.”

And so his characters are rich with personality and eccentricity. There is an inventor who uses da Vinci’s helicopter prototype to build a “flying aircraft” and become a “mariner of the air.” Savage’s sister Lizzie lets her promiscuousness become a point of feminist power. Ashley Lancaster (Vivien’s brother), the famous globetrotter and explorer, cannot have a civilized conversation with a woman. Then, of course, the devil himself lives in a “cottage” in “Essex Grove,” his personal moniker for Hell.

Leo brings these wild characters to life with charm, wit, and pomp, and he builds a fully realized — if not a little wacky — Victorian London teeming with adventure and mystery. It is worth noting that Leo was born not in England, but in Alaska and grew up using a dogsled to get to the nearest road. In a 2012 interview about his play Friend of the Devil, which is the basis for The Gentleman, Leo says that without electricity, he and his family relied on reading and telling stories, and he would often listen to his dad work at the typewriter. It is easy to picture this environment: a young Leo listening to, learning from, and experimenting with the stories that captivated him. The circumstances of his upbringing gave him the gift of pure imagination.

And yet, so much of the novel’s great appeal comes from the hilariously realistic way in which it depicts the quirkiness of writers, the idiosyncratic relationships between them, and the painstaking work of their editors. Savage has blown his fortune on books. At a dinner party, he judges the other writers by the “mangled offspring” of their work, even though he is frequently told — by his family, nonetheless — that his own work dull. He has an inflated sense of importance (“If this does not make sense to you, you are not a poet”), he resists constructive criticism, and he procrastinates and stalls against deadlines. Meanwhile, Hubert clashes with much of Savage’s writing, often disagreeing with him and asserting his disapproval of certain remarks.

“So much of the novel’s great appeal comes from the hilariously realistic way in which it depicts the quirkiness of writers, the idiosyncratic relationships between them, and the painstaking work of their editors.”

Leo’s powerful realism is perfectly illustrated late in the novel, on a page that is grossly overwritten, when a pun is stated very obviously and Savage has to “shudder” at its “double entendre,” or when he needlessly notes that “Lizzie is more persuasive than a loaded gun” right after she concludes a tirade. Moments like these can sound amateurish and overwrought, but here they are not evidence of any weakness in Leo’s writing; rather, they demonstrate the opposite — such overwriting is a symptom of Savage’s own shortcomings as a writer and thus makes him appear all the more real.

In fact, Leo’s characters are so self-contradictory and wavering that at points his grasp of them becomes suspect (or seems to). Savage reflects that he has never considered “what happens in other people’s heads” and then later claims that “faces and demeanors are to [him] an open book. [He] knows of no man more adept at reading other people.” Similarly, after railing against his “age of morality” that he does not “deem good,” Savage complains about the existence of “society men” who enjoy “muddlement” and “affairs of passion.”

If this general self-contradiction was not framed in the context of Dante, it would blow a hole through the novel’s core and deflate the rest. But Leo is smarter than that. Because he has made the mutability of the heart and mind his central theme, his characters can and do contain multitudes. Savage says it best: “When there is nothing that is level, then there can be nothing that is not level.”

Balance, at least in this sense, requires a bit of juggling. A bit of recalibration. If Don Quixote was thrust into the realm of Dante and undertook all of Dante’s grueling tasks, and if this misadventure was written in the chaotic and unconventional style of Tristram Shandy, then the resulting work would greatly resemble The Gentleman. Leo’s novel can be read as the light-hearted romantic journey of a few family members through old London. It can be read as the strange English fantasy of an Alaskan. Or, as Savage suggests, it can be read as something greater, something aspiring to fabled literary heights, “a comical epic, but with serious and indeed existential undertones.” Sometimes the best thing to do is stay lost.