interviews

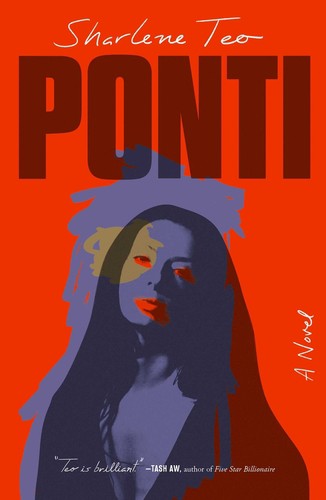

‘Ponti’ is About How Society Turns Women Into Monsters

Sharlene Teo uses the Pontianak myth as an analogy for women who refuse to conform to societal norms

Singaporean-born writer Sharlene Teo’s debut novel Ponti weaves dark, arresting narratives about the lives of three women: Szu, her distant and beautiful mother Amisa, and her high school friend Circe. Spanning between 1968 to 2020 in hot and humid Singapore, the novel traces the intimate and vicious ways in which the women’s lives are entangled to one another. Szu and Circe are drawn to the memory of Amisa and her short-lived career as an actress of a cult horror series, Ponti! As characters try to cope with loneliness and failure, the uncanny dimensions of Amisa’s film role as Pontianak, a bloodthirsty female ghost in white dress, seep silently into their daily lives. Winner of the Deborah Rogers Writers’ Award, Teo crafts each sentence with precision, evoking vivid imageries of how women experience their bodies and space, dream and reality, connection and disconnection.

I met Teo at the 2017 Sydney Writers Festival, where we spoke in the same panel and exchanged views on women, horror, and Southeast Asia. As an Indonesian writer, I was immediately captured by the universe of Ponti, which felt very close to home; similarities can be found in language, food, cultural expectations, and even in how our actions are structured by what Szu calls “a hot, horrible earth.” The Malay legend of Pontianak, known in Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia, could be seen as a projection of the fear towards women who refuse to conform to the societal norms. Ponti explore the rich cultures of Singapore and Southeast Asia while offering a fresh perspective on relationships between women, history, and (screened) memories.

A recipient of the Booker Prize Foundation Scholarship and David T.K. Wong Creative Writing Award, Teo is currently completing her Ph.D in Creative and Critical Writing at the University of East Anglia. Prior to the U.S. release of Ponti, we conversed over email about the Orientalist connotations of Asian femininity, myth-making as ciphers of fear, and turning the pockets of weirdness and decay in cosmopolitan Singapore into its own character in her novel.

Intan Paramaditha: The Malay legend of the female ghost Pontianak is well known in Southeast Asia, especially Singapore and Malaysia. In Indonesia she is called Kuntilanak, although we have a city called Pontianak, where the horror film director in Ponti comes from. What inspired you to explore this myth?

The myth of the Pontianak relates to societal anxieties and expectations around childbirth, childrearing and the female body.

Sharlene Teo: I’ve always been fascinated by the Pontianak, found something subversive, sexy and deeply threatening about her. Lock up your boys and men! She’s pissed off, well-dressed, and out for vengeance. There’s the predatory aspect of this creature, outwardly an unthreatening young woman. There’s the invasion of the domestic space, the uncanny, creepy-crawling aspect of how she mimics baby sounds to fool you into thinking she is far away, when she’s actually very close. The Kuntilanak, Pontianak, Lang Suir (and for that matter another Malay ghost, the toyol)—all relate to societal anxieties and expectations around childbirth, childrearing and the female body, to me. I think that figures of fear and horror are pariahs and ciphers for insecurity and fear—they reflect what is found, at the time, to be undesirable or repugnant. Thus zombies can be metaphors for capitalistic overconsumption and xenophobia—the monster, the neighborhood menace- is the big looming Other.

IP: Motherhood, friendship, and relationships between women are dominant themes in Ponti. Are there any assumptions about women and femininity that you wish to challenge?

ST: Asian femininity, particularly under the Western gaze, has these icky Orientalist connotations of delicacy, elegance and restraint. Like a demure madonna-whore dichotomy. I’ve noticed a welcome uptick in contemporary literature that takes into account the corporeal and scatological aspects of female experience as well as the effects of pregnancy, birth and postpartum depression on the body. The women in Ponti are mostly inelegant, occasionally unpleasant, and avid in their desires and fixations. They spend a lot of time on the outside looking in. I’m fascinated by the ways people hold each other at an intimate distance, how every small act of aggression or rejection furthers estrangement; the subtle strokes of cruelty these characters inflict on themselves and each other. Of course this behavior cuts across gender, but women are competitive and tender with each other in very nuanced and particular ways.

IP: In Ponti Amisa is often described by other characters as unusually beautiful and cold, almost inhuman, but we also see girls struggling with pimples, oily faces, sweat, and other mortal concerns. How do you approach the idea of beauty in this novel?

Asian femininity, especially under Western gaze, has these icky Orientalist connotations of a demure madonna-whore dichotomy.

ST: I remember being told as a child that it takes just 7 seconds to form a first impression on someone. And that really stuck with and saddened me. It seemed unduly harsh. The fairy stories and fables I grew up reading- from 1001 Nights to the Brother’s Grimm, the Chinese and Greek and Norse myths– all involved transformations, from plainness to beauty—as if that was the main object that girls should aspire toward, obtaining the right dress, the right face to win some earnest schmuck who happened to be a prince. It seemed so facile but all-encompassing a goal. These toxic messages continue to be passed down to little girls and boys, really, about performative gender roles and narrow (mostly Eurocentric) ideals of beauty—it hasn’t gotten any better with the interactive, all-seeing mirror of Instagram and social media and so-called wellness culture. These pressures break my heart. Physical beauty comprises the tiniest fraction of how someone really is. Yet we move through the world largely judged superficially first, everything else second. Particularly as women. Particularly as women of colour. It sucks and it’s something I keep returning to thematically in fiction. I enjoy interrogating why we are shallow, digging into this in words.

IP: When I read Ponti, the images of Singapore were very vivid to me, particularly the food, the heat, the rich hybrid Asian cultures on the streets, and — especially in the Circe story — the sense of isolation in a capitalist society. Perhaps you could tell us about how you decided to write a story set in Singapore. How do you envision Singapore in Ponti?

ST: I’m conscious of my position as a Chinese Singaporean who has moved away for a long time and both the privileges and marginality of that perspective, depending on whether you’re looking at it from within Singapore or the U.K. Singapore—as a mutable, deeply cosmopolitan city with pockets of weirdness and decay—is very much its own character in the novel. Ponti is a bit of a love letter to this city I spent the first nineteen years of my life in and which has been so formative of my psyche and development as a writer. I never wanted to depict the island state in a way that was touristic, sycophantic or cliched. Singapore in Ponti alienates, stifles and embraces Amisa, Szu and Circe.

IP: What is also interesting to me is how you portray cosmopolitanism in Asia. The horror film director in Ponti comes from Indonesia and moves to Hong Kong, and there is a reference to a Filipino film as well. How do you view Asian or Southeast Asian cultures? Are there points of connection that you are trying to make?

ST: Singapore is a country comprised of so many different ethnicities and cultures, and transnational migration and mobility in the context of late capitalism is part of what makes the pace of the city so dynamic and relentless. Globalization and the internet has radically effected culture and communication, which sounds and is an obvious statement—but narratively, it’s interesting to consider how things like cosmopolitan trajectories and mass and hype culture—were not parsed or disseminated in the same way even a decade ago.

IP: This book might interest cinephiles with its many references to world cinema, from Hollywood to Hong Kong and Bollywood films. The film Ponti is situated in the tradition of Asian B-movies. Why incorporating cinema in the story? Did cinema influence the process of writing?

Figures of horror are ciphers for insecurity and fear—they reflect what is found, at the time, to be undesirable or repugnant.

ST: I’ve always loved ekphrastic texts—the vivid, illuminative liveliness that comes from having a work described is really fun and fires up the imagination. Cinema haunts the writing both literally and figuratively—I remember reading this Roland Barthes essay, The Face of Garbo, about the face as idea, mask, object—both ambiguous and larger-than-life, how faces in cinema can seem both timeless and inscripted with death. Particularly in the context of a female actor, and all the ageist expectations imposed on them. I read an interview with Winona Ryder recently where she paraphrased a line from the First Wives Club— “There are three ages for women: babe, district attorney and Driving Miss Daisy! I just never got to play that district attorney.”

I also wanted to write a book that incorporated Hong Kong action cinema, Bollywood movies, Hollywood blockbusters, and took into account a period of quietness in Singaporean cinematic history—between the closure of film studios in the late sixties, and the rise of Singaporean auteur cinema in the mid-nineties with Eric Khoo’s Mee Pook Man which kickstarted commercial cinema productions like Jack Neo’s films in the late ‘90s.

IP: Ponti has been praised by many for its rich and compelling writing style. Could you tell us about your creative process as a writer? What were challenging for you? Which authors inspired you?

ST: I write from a place of pure, abject desperation and self-doubt, to be totally honest! I feel like I know nothing and I just try and get to the nub of feeling, what these characters who slowly and messily take shape are trying to convey. I’m not a plotter at all. I write in fragments and see how it goes. I find everything challenging. I find starting, getting through and finishing challenging. That’s not to say, in the sweet spot, the flow and throes of it, that I don’t find it a pleasure. Of course I do, I love writing and always have! But I don’t have a particular process, or I’m still figuring it out intuitively. I read a lot and try to read across genres and boundaries, which usually helps to stave off some of my anxiety and creative inertia. So many authors inspire me because of their strong voices and various methods of making a story hurt and glow in wildly original ways. Most recent terrific reads: Alexia Arthurs, Ottessa Moshfegh, Suzanne Moore, Rowan Hisayo Buchanan, Kobo Abe, Elizabeth Macneal, Niviaq Korneliussen, Dorthe Nors, Akwaeke Emezi.