interviews

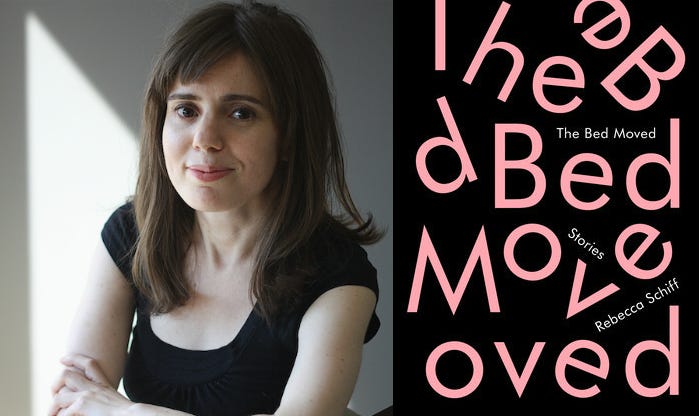

Rebecca Schiff on Humor, Crafting the Perfect Line and Casual Sex in Fiction: An Interview

by Claire Luchette

There are a whopping 23 stories in Rebecca Schiff’s slim new collection The Bed Moved, and this is just one of Schiff’s many sleights of hand. Each story is a delight — drily funny, irreverent, original. But just as they’re refreshingly candid and witty — they are very witty — Schiff’s stories also offer tender, but stubbornly unsentimental emotional truths. The stories in this collection are interested only in being honest, and that means shedding light on grief, pride, promiscuity, and loneliness in ways that are surprising, funny, and frank.

The narrator of the final story, “Write What You Know,” reflects on the titular aphorism: “I only know about parent death and sluttiness…liberal guilt and sexual guilt and taking liberties sexually.” Here is the magic of Schiff: she offers aphorisms without waxing pretentious, and she delivers humor without devaluing the emotional concerns. The book is evidence of her refreshing talent and sharp, incisive intelligence.

Schiff answered my questions about how these stories took shape, being funny, and casual sex in fiction.

[You can read Schiff’s story, “It Doesn’t Have to Be a Big Deal,” and her reading list, “Contemporary Innovators of the Short Story,” at Electric Literature.]

Claire Luchette: What I loved most about these stories is how stripped they are of all the often-clunky narrative stuff that shows up in more traditional stories, where it can seem like character biographical details and situational context are dumped into the text. It’s very refreshing. And I think that spare prose pairs so well with your humor. Tell me about being funny. How do you know when the wit lands or when something feels less successful? Are you able to judge for yourself?

RS: I’ve definitely written stuff that’s funny but lacked a greater emotional purpose. And then I can judge that I’m hiding behind the jokes. But I try and make sure the humor is connected to the emotions of the piece: is it organic to them? And then I feel more comfortable joking, because I know there’s more going on in the story.

I also, while I’m writing, often make bold the lines that I know could be funnier. And then I’ll go back later and try to push myself to make the line funnier.

CL: It’s an interesting thing — if you feel you’re funny and no one laughs, then are you actually funny? And if people tell you you’re funny and you don’t feel funny, then something’s off.

RS: Yeah! In some ways, we can’t find ourselves funny, because we’re just who we are to ourselves. It does require a kind of response or engagement. When I read aloud, some parts will get more laughs than others, and that’s a means of evaluating the humor. But you don’t often see people respond to your stuff, so you don’t know if they’re laughing or totally horrified.

CL: Who are your favorite funny writers?

RS: I love Etgar Keret. I love George Saunders, for obvious reasons. Sam Lipsyte’s very funny, as is Grace Paley. Lorrie Moore, obviously. I read her as a teenager, and she was the first person I had read who was strange and funny, and it opened up possibilities for me; I saw it could be done that way.

CL: The story “Communication Arts” is all about the challenges of teaching writing — it’s a teacher navigating all these students’ issues and requests on e-mail. What’s your approach to teaching writing?

RS: When I was just starting out, I never had control of the room — I was teaching maybe 30 kids, which isn’t so many, but is a lot if you haven’t done it before. I think that experience, of teaching composition, toughened me up. I had to be a better teacher in order to get through the day.

A lot of people seem to think student writing is terrible, but one of the things that helped a lot was I learned to find what students are doing exactly right and point it out to them. And then encourage that, instead of jumping straight to criticism. In teaching creative writing, it’s a bit different, but the same principle applies: look for the place where the magic is coming through, where you can see the student’s voice. And help the students see that in themselves, what’s working.

CL: How do you approach teaching “the rules” of creative writing?

RS: The thing about rules is that when a writer creates her own rules, she still has to follow them. Which, in a lot of ways, is even harder. Restrictions on a story — putting limits on it — can be really helpful.

Most of my students seem to want to know the rules — know some straight-forward way to write a story, like you would a five-paragraph essay. But of course that doesn’t exist.

CL: You have such a knack for first lines. Each of these really start with a bang. Some favorites: “She slept with men who only wanted to play Settlers of Catan.” “The pot grower was broke.” What are some of your favorite first lines in stories?

RS: Off the top of my head, there’s Leonard Michaels’s “In the fifties, I learned to drive a car.” The story’s called “In the Fifties.” It’s kind of like a list story, a non-traditional story. It’s such a specific first line, and then it allows the story to grow from there.

CL: What do you think any first line should do for a story?

RS: I think it’s mostly instinct. I’m not in love with all my first lines, but for a lot of stories I found my first line only after I started writing — after a couple of paragraphs, so I could see where the story really starts, where the good stuff begins. They say a line should draw you in, but it should definitely establish what we’re dealing with here…One way to start is with a lot of information. There’s that Joy Williams story, “Honored Guest,” and the first line tells us so much: “She had been having a rough time of it and thought about suicide sometimes, but suicide was so corny in the eleventh grade and you had to be careful about this because two of her classmates had committed suicide the year before and between them they left twenty-four suicide notes and had become just a joke.” Williams just takes it so much further in a way that establishes the tone, and it takes you a place you don’t expect.

CL: These stories are concerned with women who are navigating their worlds and are often dissatisfied. How do you describe the stories’ “aboutness”?

RS: I think the aboutness reveals itself to me as the stories unfold. I don’t always know why I start to write about something, and usually I’m interested in certain emotions or language, and I enjoy the way words sound together. But the way stories develop, I start to keep track of what characters are going through and what’s happening for them…I have trouble with that question, “What are your stories about?” I have trouble answering that. I usually say, “They are what they are!” They are about women getting through, or figuring out how to get out, or whether or not they should get out. It’s hard to see what your own work is about.

CL: In “Little Girl,” the last lines do such a great job of describing what it’s like to leave a lover’s place: “Some of the buildings had elevators and she enjoyed the anticipation of the ride up, the soreness on the ride down. What happened in between almost didn’t matter. She’d wind up back where she started, walk into the street, and hail a cab.” It’s so good! What do you understand as what happened “in between”?

RS: It’s the sex, but this woman is having so many of these experiences that the only constant is herself. There’re all these guys, and they have sex or talk or hang out, but the experiences all kind of blur together. What do you think happens?

CL: It’s almost like a commercial break, like these one-night stands are just distractions. A brief vacation.

RS: I like the idea that it’s a vacation. So many people think of casual sex as just depressing, and in my stories in this collection, I tried to present it as otherwise. It can be, but it can also be exhilarating and funny. There’s a lightness to it! For that narrator, she’s having a good time, but she’s also not.

CL: In Girls, we indulge in the awfulness of the sex. And in Broad City, it’s like it doesn’t end up mattering.

RS: Yeah. I like both shows. I think both wouldn’t exist without Sex and the City, and I fall between those generations. I don’t think I would be the writer I am without Sex and the City. I don’t know if that’s suicide for a literary writer to say, but I think it opened up the culture, and allowed us to start talking and thinking about sex.

CL: The final story, “Write What You Know,” is so funny and good. Tell me about your experience writing what you don’t know.

RS: I think the writer is always doing both simultaneously. There are things you think you know, and you start there, and it turns out that there’s a lot you don’t know — about a story, a situation, a plot. I’m always learning the way I feel about something, through writing fiction.