essays

REVIEW: The Angel Esmeralda by Don DeLillo

R

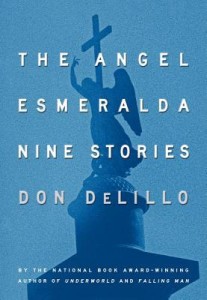

The Angel Esmeralda

Don DeLillo

Scribner

224 pp / $24

Don DeLillo has been a powerful presence on the American literary scene for the past four decades, and his latest short-fiction anthology, The Angel Esmeralda, encapsulates some of his lasting concerns and themes. In it, the readers will find the familiar landscape of psychological alienation, sardonic treatment of mass media and western consumerism that absorbs and savages any meager attempts at transcendence.

DeLillo has the rare gift for capturing the linguistic verve of advertizing (he had worked as a copy writer), while simultaneously sabotaging it. He achieves the muscular rhythm of his prose by often using punch lines and refrains, with sentences whose content sometimes sounds so truistic that it has led some critics to accuse him of hollow existentialism. His technique can perhaps be likened to that of the American post-pop artists, who appropriate the objects and the language of mass culture, to manipulate them.

His use of postmodern/new-agey zeitgeist can be seen in the story “The Starveling.” The narrator comments on his drifting apart from his wife:

It had something to do with Flory’s worldview. She dropped out of the neighborhood association, the local acting company, the volunteers for the homeless. Then she stopped voting, stopped eating meat and stopped being married. She devoted more time to her stabilization exercises, training herself to maintain difficult body positions, draped over a chair, rolled into a dense mass on the floor, a bolus, motionless for long periods, seemingly unaware of anything beyond her abdominal muscles, her vertebrae. To Leo she seemed nearly swallowed by her surroundings, on the verge of melting out of sight, dematerializing.

If this passage is funny, it is savagely so: a relentless snapshot of a personality and a marriage unraveling, and an acerbic commentary on a society in which we are more and more often willing to form “relationships” with fantasies (including whatever new self-help ideology is in fashion), or things (video games, gym, TV). The collection is full of stalkers — two university boys follow an old man and invent his life story in “Midnight in Dostoevsky;” an older divorced man trails a young woman he spotted alone in a movie theater (weaving a made-up tale of her life along the way) in “The Starveling.” More than an addiction to voyeurism, or to daydreaming, the characters convey a sense of muted despair — a frightful, almost unspeakable knowledge that our usual forms of communication, e.g. language, sensation, have somehow broken down. Sometimes, humans are replaced altogether — in “Human Moments in World War III,” an astronaut stalking unmanned satellites in outer space would rather communicate with the soulless universe than with his colleague (“his human insights make me nervous”). The “human moment” is reduced to interacting with objects: hammocks, earplugs, broccoli. It is a bleak vision, as if language’s failure has forced us to retreat to our most rudimentary foundations.

A distancing tendency permeates DeLillo’s fiction. Sometimes in a more innocuous way — in “Midnight,” the fictional narrative that the boys invent feels so real it becomes an end in itself (what postmodern theorists call “hyper-reality”). Luckily for readers who favor character-driven fiction, in this particular instance, DeLillo is more interested in depicting a human affair with language than in theories — his characters are seduced by words, by their power to dictate and change how we view life, ourselves. It is a beautiful allegory of both imagination and evolution in general — of how we come to acquire a “world.” In “Hammer and Sickle,” a story about white-collar criminals in a low-security prison, the narrator confesses that just hearing the word “phantom” made him want to be “phantasmal.” But language deceives as much as it seduces. The convict adds, “here I am, a floaty fever dream, but where’s the rest of it?” In the most moving stories, the instant gratification of language is offset by the writer’s skepticism.

In some of the more transparent passages, on the other hand, human beings feel more like thinly veiled manifestations of phenomena. In “The Starveling,” the male narrator reflects on why he has stopped taking movie notes:

He stopped, he said, because the notebooks had become the reason for what he was doing. What he was doing was going to the movie. The notebooks were beginning to replace the movies. The movies didn’t need the movie notes. They only needed him to be there.

The passage fails to convince as an explanation of the character’s psychological motivation. In another instant, in “Hammer and Sickle,” the narrator’s two little girls appear on children’s television to deliver a stock-market report. While hilarious, the girls’ presence, or the convicts’ fascination with them, feels contrived, leading too quickly to musings on the demise of global markets and the cancer of capitalism.

The inclusion in the collection of the eponymous “The Angel Esmeralda” may seem surprising, at first — the old nun Edgar’s story appears in DeLillo’s masterpiece, Underworld. So much here echoes the passage in the novel, the pleasure lies not in novelty but in revisiting what may be some of the very finest contemporary American writing. In a single story, DeLillo encompasses both the malaise of a postmodern cosmopolis — littered with debris, ridden with drugs, crime, and ad-hoc capitalist enterprises raised in the ruins of an impoverished community — and the apocalyptic, mythic vision, encapsulated in a young runaway turned saintly apparition. That the apparition turns out to be a bust — a reflection, made by the lights of a passing train, against a sprawling ad for orange juice — hardly takes away from its power. The Angel Esmeralda is a simulation par excellence, and it would make Jean Baudrillard proud: once the angel becomes a media event, drawing in crowds (and tacky commerce) and bringing the onlookers to a near catharsis, who’s to say that the fakery (or the non-existence) of the ghost matters? The event and its afterglow, processed by the media and perpetuated by the converted, creates a new kind of reality. What makes all this possible, DeLillo suggests, is our human need to create myths (urban legends), and to become part of something greater than ourselves — as is the case of Edgar, who feels “nameless for a moment, lost to the details of personal history,” and for whom the angel is “the vision you crave because you need a sign to stand against your doubt.”

The literary critic Harold Bloom has questioned whether Don DeLillo is in fact postmodern. Bloom may be right: in the most engaging stories, like “The Angel Esmeralda,” the writer’s brilliance seems to lie not so much in channeling the ills of our age, but in juxtaposing the old systems of belief with the new. It is a cry for what has been lost, as much as a pastiche, in the Jamesonian sense, of our age’s questionable gains, and the resulting mix is full of tension and inventively surprising.

The Angel Esmeralda Signed 1st Edition

by Don Delillo

***

— Ela Bittencourt has an M.F.A. in writing and an M.A. in arts administration from Columbia University. She is currently based in New York, where she writes book and art reviews, as well as fiction.