Books & Culture

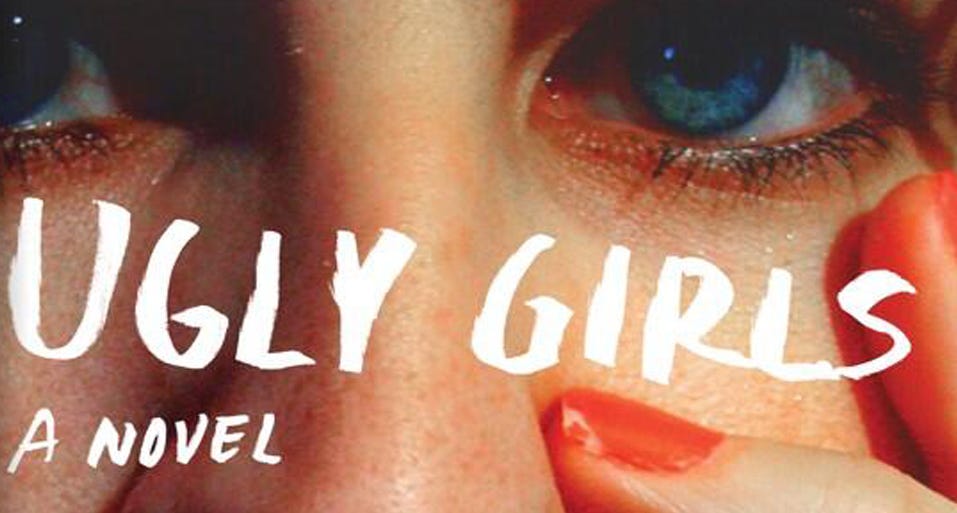

REVIEW: Ugly Girls by Lindsay Hunter

by Drew Smith

“Some people like being ugly I guess,” says the narrator of “Dishes,” from Lindsay Hunter’s 2013 collection, Don’t Kiss Me. In the opening paragraph of that story, the word “barf” appears three times, a woman watches her husband as “his shorts bunch in his ass,” and when the same woman’s son confuses Texas for Oklahoma, she thinks, “it’s no skin off my tit.”

Ugliness in Hunter’s work isn’t an isolated theme. Don’t Kiss Me, like Hunter’s prior collection, Daddy’s, overflows with vomit, junk food, boogers, belches, gross sex, farts, smelly sweat, cigarette butts, tapioca pudding fat, hangovers, beer shits, and lower-class dialect, along with its inevitable double negatives. Now, having read her novel, Ugly Girls — what else could it be called? — the assertion that some people just like being ugly reads less like a passing observation and more like the key to Hunter’s oeuvre.

Her authorial preoccupation with the ugliest parts of poverty brings to mind a similar fixation in the parallel career of film director Harmony Korine, whose work I’ve seen described as “ugly people doing ugly things.” His trademark, per IMDB, that he “often depicts teenagers doing violent and disturbing things” could just as easily be applied to Linsday Hunter.

But it’s not merely their chosen subject matter that links the two. The evolution of Hunter’s writing over the course of her three books mirrors in many ways Korine’s arc from his earliest film, Gummo, to his latest, Spring Breakers.

Similar to Harmony Korine’s leap from independent maverick to mainstream director, Lindsay Hunter has, of late, made her own leap from the inarguably terrific indie press, Featherproof Books, to the apex of mainstream Big Five literary publishing, Farrar, Straus and Giroux — first with the paperback original Don’t Kiss Me, and now with the full-fledged hardcover release of Ugly Girls — a trajectory that might be summarized as The Great American Publishing Dream of the Modern Era.

Like the centerless, vignette-based Gummo, Hunter’s early work in flash fiction functioned as a collage built of glimpses into a certain type of white American existence, staged in dirty suburban houses, dinged-up cars, and depressing all-night diners. As with most flash fiction, plotlessness is all but taken for granted. The mood is what’s matters, or the image. Capturing an instance or a feeling of grotesqueness appears to be primary among Hunter’s aims.

Similar claims have certainly been made about Gummo, though I’d argue there’s another element at play in Korine’s work that remains unexplored in Hunter’s. The humanizing details he dwells upon between depressing freak show episodes suggests a greater meaning behind the ugliness — if not beauty exactly, then at least complexity and depth. Reading Hunter’s stories, one sometimes feels that ugliness itself is the statement. Full stop. While the writing is reliably strong, and the author demonstrates a genuine talent for creating clear and memorable images, the work frequently leaves me longing for a deeper level.

In Korine’s Spring Breakers, he parts ways with more abstract techniques in favor of a more traditional (for him, anyway) narrative. In Ugly Girls, Hunter does the same. Both works tell the story of bored girls seeking fun and escape through theft, sex, and the attention of a man who could probably teach them a thing or two about being bad. However, it’s worth noting that in both cases the girls are already criminals by the time their respective men enter the story.

While Korine populates his film with broke college party girls, Hunter’s cast of characters — trailer-park dweller Perry and her best friend and fat wannabe-gangster, Baby Girl — are high school outcasts with little hope of pursuing a higher education. Other characters include Perry’s parents Myra, a sex-and-attention-starved alcoholic who can barely hold down a job at the local truck stop’s donut shop, and Jim, a prison guard — easily the least pathetic and awful character in the book. There’s also the hare-lipped parolee pedophile and his freakishly obese mother. And of course Baby Girl’s older brother, a one-time stud and neighborhood idol left with the mind of a child after an accident.

Hunter brings the full weight of her considerable strengths and nagging weaknesses to Ugly Girls. While she makes the transition from flash fiction to full-length novel look easy — not something most authors carry off so gracefully — she persists in her fixation on her usual bleak subject matter with no apparent deeper meaning to justify such extreme cynicism and darkness.

Hunter doesn’t merely turn her eye to life at its most bitterly unromantic; the fervor with which she seeks it out rises almost to the level of compulsion. Nothing is ever ghastly enough. Baby Girl’s brother can’t merely polish off an entire box of sugar-covered breakfast cereal or wail like a disturbed autistic first grader. His penis must wag from his open fly. He must forget to flush the toilet after defecating. It isn’t sufficient that the hare-lipped pedophile endures the incestuous semi-overtures of his whale-like mother. He must rub her disgusting feet with lotion.

“She moved her toes, their sour smell familiar to Jamey, the definitive smell of his momma. He dumped on more Jergens.”

It’s a complicated mix. There is a definite development on display in Hunter’s work. With each book, the writing grows more certain and more overtly well-constructed. And she’s unquestionably skilled at sketching her bummed-out characters and their milieu. By the end of the first page she’s already displayed her unique power thorough such grim descriptions as a “sad rag of a paycheck” and “the rising sun the color of a pineapple candy, no more than a fingernail on the horizon.”

There’s something undeniably intriguing about the ugliness of Ugly Girls. The writing compels with the strength of a funnel. The guarantee of life’s inevitable worsening brings with it a peculiar pleasure, a morbid fascination in seeing just how bad it can get and where it all might end. But there’s also the threat of going too far, of becoming so extreme it’s comical; like the Debbie Downer skits on Saturday Night Live, in which the slightest shred of optimism is immediately destroyed by a litany of reminders of just how awful the world truly is. At times, Hunter’s relentless darkness risks turning whatever she’s trying to reveal into a joke. Korine avoids that fate by establishing a comic element in his work to contrast the awfulness, injecting instances of humor, giving you something amusing to look at, a point of fascination or even joy. Hunter offers no such relief from her characters’ spiraling world.

by Lindsay Hunter