Interviews

Robin Black on Memoir, Craft and Violating Taboos: An Interview

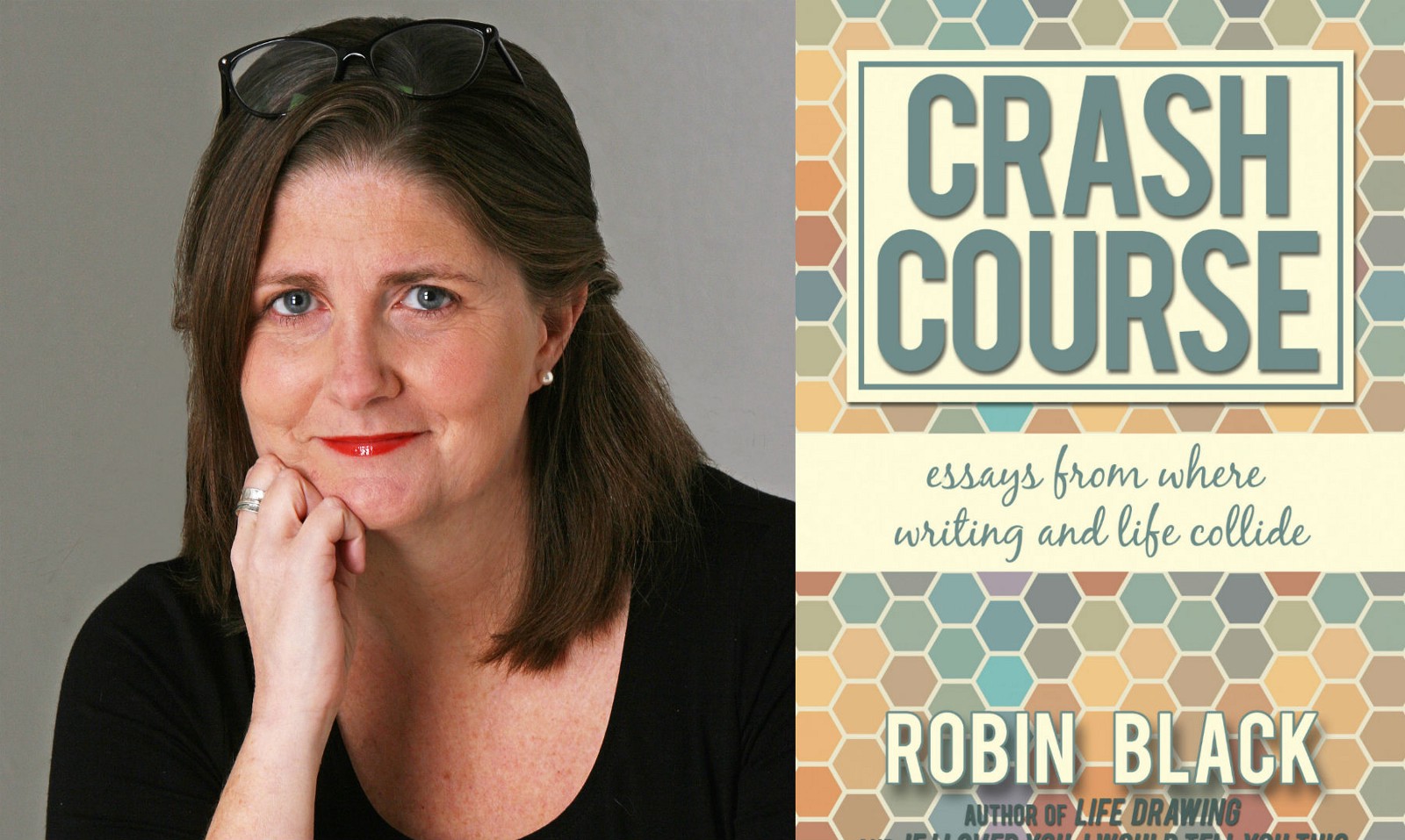

Robin Black, author of the novel Life Drawing (Random House, 2014) and the story collection If I Loved You, I Would Tell You This (Random House, 2010), has recently published her first nonfiction book, Crash Course: Essays From Where Writing and Life Collide (Engine Books, 2016).

Crash Course is part writing guide, part meditation, and part memoir. Over the course of 43 compact essays, Black, who began her writing career near the age of forty, shares stories of her own frustrations with her later start as a writer and her current struggles in her writing practice, detailing her experiences in a way that offers guidance to other writers and a candid glimpse into her own writing life.

I first met Black at a writing conference in 2014 after reading her short story collection, and subsequently enrolled in a workshop with her. For those who are unable to study with her in person, Crash Course offers the next best thing: spending time with Black via her stories on life and writing, all told in an incisive and honest voice.

I recently had the pleasure of asking Black some questions via email. We discussed the structure of her book and the selection of book titles, anger as an antidote to silence, and the particular challenges of writing nonfiction.

Catherine LaSota: Your book is called Crash Course: Essays From Where Writing and Life Collide, which is a great title, as your essays very much seem to address the experience of figuring out how writing can fit into the many challenges that life throws our way — sometimes it’s a matter of just diving in and trying, again and again. Can you talk a bit about the selection of this title, and your decision to organize the book into two sections, called “LIFE (& Writing)”, and “WRITING (& Life)”?

Robin Black: I have a super checkered history with titles for fiction. In general, I’m just bad at them. I really think there should be a Title Shop, like the Wand Shop in Harry Potter, where you can bring your manuscript and have a wizard match it to its true title. I think that on some level, when it comes to fiction anyway, I have basic questions that I’ve never answered to my own satisfaction about what titles are meant to do. I used to have this idea that titles should give you an idea of what a story is about and the story should in turn clarify what the title means. But the more I ponder it, the more I think that’s way too formulaic. So with fiction I have been caught in that zone of “I want it to sound intriguing, but kind of be related to the story, but not give too much away…” And I don’t want it to sound like whatever the title formulation of the year is — while being pretty terrible at coming up with my own ideas.

With this book, which is nonfiction, it was in many ways a relief to realize that I did want to tell people what the book’s about, in part because it’s an odd book, a hybrid of memoir and craft, and I needed to convey that. But in fact, almost no thought went into its title; it just came to me, as they say. So while my fiction books have all been called many things before landing on the final name, this one was always Crash Course.

The decision to have the LIFE (& Writing) and WRITING (& Life) sections also grew out of the oddness of the collection. It really is a kind of mash-up of stuff about me and my (awful word) journey to becoming a writer, and also to not becoming one for a long time, and actual craft topics. At first I toyed with smaller categories, essays about houses, ones about age, ones about psychological issues, and so on; but those arrangements felt fractured, so I just went back to the basic fact: it is a book about life and a book about writing and some essays lean one way and others lean the other way.

CL: Can you tell me about the process of selecting which of your essays to include in Crash Course? Did anything surprise you in re-reading essays that you had previously published, or in bringing these essays together for a collection?

RB: Mostly, it was a matter of discarding essays that I felt were weak or, in some cases, that simply tipped things too far in the direction of craft. I never wanted this book to be just for writers. I wanted whatever craft stuff there is to be interesting to any reader if only because those essays illustrate ways to think about writing that are tied with thoughts about how life is lived — or anyway, how my life has been lived. So, for example, I cut a very long essay on point of view. I had an intuitive sense of just how far into being either pure memoir or pure craft any essay could be. A few were reworked a bit to fit into that range.

I think of the book as one long collage piece. There is the whisper of a narrative arc to it, but the way that the individual pieces relate to one another has more the feel of multiple interactions than of a linear progression. Once I understood that, I felt much more comfortable with the whole project, with the fact that it is not exactly a recognizable type of book. That freed me up to do things like have a two line “essay” in there.

CL: In an essay entitled “Shut Up, Shut Down,” you write that “So many writers felt silenced at a critical point in their lives” and ask if writers’ block is perhaps a result of having internalized the message that if we fully express ourselves we are somehow “bad.” You write about your own sense of being silenced in Crash Course, which really resonated with me personally. Would you share a bit about your own experience feeling silenced here with our readers?

This has largely been a project of self-forgiveness…

RB: I’m glad it resonated for you — though I’m also sorry, because I know that indicates some painful stuff for you. For me, part of beginning to write in earnest at just about forty has been trying to understand what took me so long. This has largely been a project of self-forgiveness, because for a very long time I was in a chronic rage at myself for having let so many other things get in the way. And to this good day I have some pretty serious sorrow over not knowing what my own “young” work might have been like; and what my middle-aged work might be like, were I not playing catch-up, were I not so conscious of public responses to, assumptions about, dismissals of, middle-aged emerging writers, especially women. Were I free of this whole “late bloomer” thing — and were just a writer.

So to understand all the self-sabotage that went into delaying my work I have had to do a lot of work to see it in terms beyond my just being a fuck-up in my twenties and thirties. And the central fact that has jumped out is that I started to write three weeks after my father died, when he was eighty-five and I was thirty-nine. I have come to understand the degree to which his living presence in my life kept me quiet. In my case, that silencing had a lot to do with his emotional make-up, his messages to his children that they were not to try to succeed too much, lest they eclipse him, and also with the general shroud of secrecy around our family due to his alcoholism. And there’s more. He was a complex figure, by no means all bad; but the particular mix of good and bad, of intimidating and pitiable, that he was, shut me up.

And when I realized this about myself, this phenomenon of having internalized an inhibiting voice, I began to wonder about others, and I have yet to meet a writer who doesn’t feel that something analogous was true of them. And of course it’s also true that many people who aren’t writers have felt silenced along the way, but writers are in the position of both having that circumstance and choosing to violate the taboos. So it is a complex, sometimes dangerous dance.

CL: I’ve heard you talk in a writing workshop about this common experience of writers feeling silenced at some point in their past. In workshop, you’ve asked students to think about when the moment of silence may have occurred for them, and you offer the advice to get angry at those voices who silenced you, as a means to fuel the writing. Have you witnessed students heeding this advice and the results it generated? Is this a method you employ in your own writing practice?

The act of writing, absent some sense of danger, of risk, is likely too tame a pursuit to produce anything like art.

RB: I have seen students respond with great emotion to that idea, but knowing that it took me decades to understand the impact of those inhibitions on my own life, I don’t expect other people to be immediately liberated by my just suggesting that they may need to be. I say it more as a nudge toward understanding that being able to write, to get words on the page and keep doing so until you are pleased with the result, is not just a matter of how many minutes a day you do it, or even of having the craft understanding to whip such things as narrative distance into shape. It’s also about owning up to and supporting that as a writer you are almost certainly breaking some taboo that you have internalized along the way. And that’s a good thing to do, but not an easy one. I’m not big on sweeping comments about writing, but here’s one: Great writing shouldn’t feel safe, to its author. The act of writing, absent some sense of danger, of risk, is likely too tame a pursuit to produce anything like art.

In my own work, the process of getting angry at the forces that led me to accept that I should be silent has, as I said, taken decades. It is ongoing. The sensation of being a “bad person” for daring to express myself fully will probably never leave me. But knowing that makes it easier for me to do so.

CL: In your essay “The Parent Trap,” you argue that authenticity of passion is just as important as authenticity of experience in choosing subject matter. There is sometimes debate over whether writers are justified in writing from points of view (e.g., gender, race, socioeconomic status) that are wildly different from their own experiences. Can you elaborate on your thoughts on this? What role does research, if any, play in the development of characters in your work?

RB: That statement comes in the context of suggesting that someone like me, who has led a largely domestic existence, home with the kids for years and years, needn’t be limited by the walls of her house in terms of subject matter. More generally, I have thought about this issue of authenticity a lot, and reached the conclusion that the only answer can be that writers can write whatever they want — but then readers can also respond to it critically, angrily, politically, and can decry it, and can feel that it was a bad thing to write, and should do all those things if that’s what they believe. But there just cannot be a standard or a set of rules whereby we tell people what they are and aren’t allowed to write. That is unacceptable if only (but not only) because it opens up the question of who gets to decide. But speaking up against cultural (or other) appropriations that offend is also a part of an artist’s obligation. I have reacted angrily to what I saw as the “use” of a child with disabilities similar to my daughter’s, in a work of fiction. I felt strongly that the author “shouldn’t have written that.” But there is a difference between saying you don’t think someone should have done something, thinking they are hideously wrong to do so, suspecting their motives, and thinking they should be prohibited from doing it.

And, of course, the people whose realities are being appropriated or misrepresented or used have the final say on whether or not the work is offensive. I am a big believer in the idea that those who are offended by someone’s take on them or appropriation of their culture, gender, race, religion, sexual orientation, and more, are de facto correct. Because, again, no other approach is acceptable. Who else can decide if they “should” be offended? Nobody.

In my own work, the area where I have run the highest risk of treading where I might offend through appropriation of a kind, is the area of disability and disease — and also people who have experienced losses I have not experienced. I have written about a blind girl, about a man with Alzheimer’s, about a man with a significant speech impediment, about an elderly woman who has had a stroke, and about a woman whose mother died when she was a baby, and so on. And I would say that over the past fifteen years I have grown more careful about being sure that I am “getting it right,” which for me, with those particular things, means talking to people who have experienced them. That is the best research I have found. I’m very, very aware of not wanting to use other people’s suffering just to increase the sensationalism of my own work.

CL: Your two previous books are works of fiction. I’m curious how your fiction practice and your nonfiction writing practice inform each other. Do you work on fiction and nonfiction writing at the same time, or do you go through periods where your focus is on one or the other? Many of the essays in Crash Course discuss personal aspects of your own life with great honesty. Did you encounter particular challenges when writing about your own life that are distinct from the challenges of writing fiction? How was the experience of publishing a book of nonfiction similar to or different from publishing a work of fiction for you?

RB: I tend to work on many things at once, and almost always have some essay or essays going, no matter what’s happening with my fiction. It is easier for me to write essays. Fiction requires a flip into an imaginative mindset, and that’s much less reliably possible for me than is doing anything approximating analytic work.

Having this book out in the world is indeed different from having fiction out in the world. It’s early days, and I’m still learning in what ways it’s different, but for one thing, these essays are about me. Which means that in writing this book, I am asking people to care about me, and I am asserting that by learning about my life, my struggles, other people will benefit in some way. And that’s very different from asking people to care about or engage with fictional characters. So I feel a little bit embarrassed by that. By the inescapable me, me, me of memoir.

And I suppose I’m also intermittently shocked by how open I have been about some things. All those years when I suffered from agoraphobia, all the ways in which I handled what I perceived as ‘my failed life’ ungracefully. These didn’t feel like tough disclosures as I was writing, because I understood very clearly why I was sharing the messier side of my experiences. But then, when people say things to me like, “I can’t believe how honest you were!” I experience a little startle, because, yeah, in some ways I can’t believe it either.

There are also areas that required special care. My daughter has learning and social disabilities, but is fully capable of giving or withholding permission for me to write about her, and it was important for me to know that she felt comfortable with the book. And as for my late father, who is featured prominently as a complicated and difficult person in my life, I thank my mother and brothers in the back of the book because they have always encouraged openness about him. I’m sure there will be people who knew him who think I should have left some of that out, but luckily they didn’t get a vote. To the extent that I had some good motives for writing this collection, they have to do with helping people who find themselves in similar situations, ones in which silence is the fuel on which an agreed upon, false ‘reality’ runs; and had I left my father out, the project would have been gutted.

CL: You have been very open about your struggles with ADD and even have two essays in Crash Course that have ADD in their titles. In what ways, do you think, has ADD affected your writing practice? Do you structure your approach to writing in a certain way in response to this?

RB: I definitely do. For one thing, I have had to reject all the writing advice out there about routines, habits, anything that suggests regularity. Maybe some people with ADD actually benefit from schedules, but I have never met a schedule I couldn’t annihilate in a single day. So I have had to learn to be patient with the fact that I cannot write every day — much less at the same time every day. And also that in the middle of writing anything, I may think of something unrelated that causes me to wander away for minutes — if not days.

ADD is probably also behind my needing to work on many projects all at once. And it’s probably why outlines feel like death to me. The ADD brain needs to have the freedom to have things occur, to change course. It’s just how we think.

The flip side though is the hyper-focus aspect of ADD. It’s not such a great thing if you have anywhere to be, or are supposed to be cooking dinner by a specific time, but it’s true that once I fall into that state, the house could be falling down, and I’d have no idea. And part of my love-hate relationship with my ADD is that I would hate to give that part up.

CL: In Crash Course, you lament the years you spent away from writing, and away from reading. I think often about the fact that there are so many books in the world that none of us are ever going to read all that we hope to read. What do you spend your time reading these days? Any recent books in particular you recommend?

RB: I still don’t read as much as I’d like to. And I admit that during this election season I have spent waaaay too much time watching the news. But the three recently read books that come first to mind are Pamela Erens’s soon to be released Eleven Hours; Leslie Pietrzyk’s This Angel On My Chest; and Robert Thomas’s Bridge. Each is extraordinary, and they share the qualities of being intense, urgent, and of feeling necessary. I love books like those three for the pure pleasure of reading them, but also for the guidance they give me as I sit back down to fiction. They are what I want to be doing. I want to be that good. I want to know, as I do when I look at their pages, that it is theoretically possible for work to be compelling and brilliant and true.

CL: What books or other media do you turn to when you feel stuck in your own writing?

RB: When I feel stuck, I do visual art. Or I garden. Or I paint a room. Doing that puts me in touch with my creativity beyond the pressure of language. And in fact during the years and years when I was unable to write at all, I painted, I did ceramics, I drew, I even decorated cakes semi-professionally for a while. When words fail me, making stuff, really making anything, is my bridge back into the work.

CL: Your book offers so much wisdom for writers who want practical advice on how writing fits into a life. I really love the section called “Twenty-One Things I Wish I’d Known Before I Started to Write,” which includes tips such as “You cannot write the pages you love without writing the pages you hate” and “Don’t believe there are rules.” What is some of the best writing advice you have heard or read over the years?

RB: This is a tough one, because there is always the caveat that what’s been good advice for me is not necessarily good advice for anyone else. There’s that tension to the whole idea of writing advice. But here are a few, from the crafty to the philosophical: Don’t let your characters be too comfortable. Don’t have them talk too directly about whatever is under discussion. Be aware if you have a clock running in your work — for example, if a story begins at the start of a two week vacation, be aware that your reader is likely to expect it to end at the end of the trip. Don’t necessarily end it there, but be aware of the expectation — and use it if it helps. Don’t share work too soon. Don’t listen to people who hate your work. Don’t agree to edits that you know in your heart of hearts are wrong. Just don’t. Really, don’t. But don’t refuse edits until you have thought them over for a day or more. Apologize when you hurt someone’s feelings — I guess that’s important for every profession, but in this world of workshops and feedback and everyone’s soul exposed, hurt feelings can be common. Don’t sweat too much over whether you were right or wrong, just apologize. Don’t think you know better than a colleague what she should be writing. Don’t try to be anyone but yourself, but don’t assume you know who that is from project to project. We change. We grow. Our work can do that, too. Don’t fail to appreciate whatever small or large successes come your way. It’s way too easy to forget to count one’s blessings because someone else seems more generously blessed. Read a lot. Be kind. Keep trying. Never give up. Never. Give. Up.