interviews

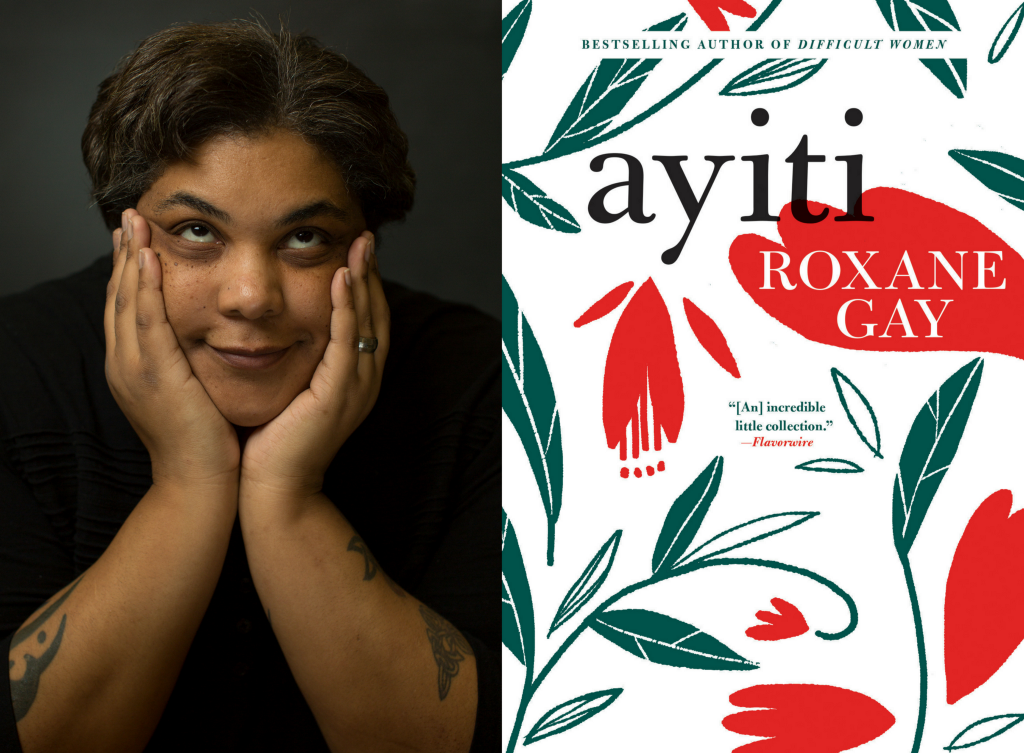

Roxane Gay on the Trauma and Triumph of the Haitian Diaspora

The author’s recently reissued short story collection ‘Ayiti’ explores beauty, desire, and resilience of Haitian people

“When my college roommate learns I am Haitian, she is convinced I practice voodoo, thanks to the Internet in the hands of the feeble-minded.” So opens the short story “Voodoo Child” in Roxane Gay’s recently re-released short story collection, Ayiti (the title is the creole word for Haiti). The people in these stories are tired of the assumptions, tired of everyone getting their stories wrong. The news cycle doesn’t help.

The stories create conversations that travel back and forth between Haiti and America to challenge the overpowering news narratives that undermine the beauty, desire, and resilience of the Haitian diaspora. The stories vary in length, and in each Roxane Gay illustrates how expansive the short story form can be. While some stories cinch an idea into two pages, another develops over 45 pages. The structures for her stories are novel and purposeful. “There is no E in Zombi, Which Means There Can Be No You or We,” for example, opens with a “[Primer]” told in verse: “[Things Americans do not know about zombis:]/They are not dead. They are near death./There’s a difference.” “Gracias, Nicaragua y Lo Sentimos” is a two-page short story written in Spanish and English in allegiance to the experience of being reduced to your country’s political and economic strife.

A glance at Roxane Gay’s work since Ayiti was originally published in 2011 illustrates the point we already knew — Roxane Gay is as prolific as she is purposeful. Since 2011, Gay has published a novel An Untamed State, the New York Times bestselling essay collection Bad Feminist, her second short story collection Difficult Women and her memoir, the New York Times bestselling Hunger. She also writes the World of Wakanda comic book series with poet Yona Harvey for Marvel, and is a contributing opinion writer for The New York Times. And she’s at work on television and film projects.

On the reissue of Ayiti this year, Roxane Gay and I corresponded over email about conveying the multiplicity of the Haitian diaspora experience.

Erin Bartnett: Ayiti was originally published in 2011 by Artistically Declined Press. A lot has happened since 2011. Do you relate to the book differently? What were you hoping to explore in giving this book a new life?

Roxane Gay: My relationship to this book is largely still the same. When I collected the stories in Ayiti, I was working thematically, pulling together all of my work that had to do with the Haitian diaspora. In re-releasing this book with Grove, I wanted to give this work a larger audience.

EB: Do you think the audience for this book has changed? How?

RG: The audience for this book has grown. The people who read the original version of Ayiti were my early adopters, if you will — people who knew my work in the small press community and came to my early events when I was driving all over the place, hustling, and trying to break through. Now the readers for this book include those original readers, but also people who have learned about my work from my other books like Bad Feminist or Hunger or An Untamed State or Difficult Women or some of my opinion writing in the Times.

Roxane Gay Is Feeling Ambitious

EB: What informs your decision to write through an idea in fiction versus nonfiction? You’re someone I think of as being extremely aware of what different structures — and particularly different genres — can hold. Does audience have anything to do with it? Or does the idea come before you’re even thinking about how to classify it for someone else?

RG: Generally, my nonfiction is solicited or something happens in our culture that I feel the need to respond to. With my fiction, I have all the time in the world, so I let ideas percolate. An idea enters my mind and I latch onto it and from there I start thinking through the story, the characters, the sense of place I want to evoke. The reality of my current writing life is that I don’t have a lot of time to think about what I want to write beyond what is due. It’s a good problem to have but it is a problem nonetheless.

EB: Do you find these classifications useful or distracting?

RG: Genre is incredibly useful but it should not be seen as something meant to limit creativity. Rules matter but they were also made to be broken.

I think of triumph as the defining feature of the Haitian diaspora and on the way to triumph, there has been trauma.

EB: I was really taken by the way you create a balance between two competing urgencies after trauma: the necessity for story, the urgency characters feel for telling and sharing stories, but also the perpetual shortcomings of story. There is a haunting absence, even in the telling. And this is particularly heightened by the trauma of the Haitian diaspora. How does the trauma of the Haitian diaspora inform the way these characters think about the relationship between storytelling and survival?

RG: I don’t think of trauma as a defining feature of the Haitian diaspora. I think of triumph as the defining feature and on the way to triumph, there has been trauma. These characters tell their stories because they want their stories known. They want their circumstances to be understood and seen.

EB: Beautifully put. As an extension of the last question, when it comes to the experience of forced migration, the separation of families — especially in the horrifying reality of our present moment — do you find the short story more accessible for making circumstances understood and seen?

RG: Short fiction is an ideal medium for bringing to bear the horrifying reality of our present moment. It allows the comfort of distance provided by fiction but also allows an unbearable intimacy of painful truths. It engenders empathy by getting readers to care about circumstances other than their own.

EB: You’ve made the critical distinction between the trauma and triumph of the Haitian diaspora. The word “trauma” means a lot of different things to different people. How would you begin to shape or define your relationship to the word?

RG: Trauma is something that has informed my life, by way of experience and my work, by way of where that traumatic experience took me and what I needed to say about it. As I get older, my relationship to trauma changes. With time there is distance and healing though as I write in Hunger, I am as healed as I’m ever going to be at this point.

Is Roxane Gay’s ‘Hunger’ a Memoir or a Polemic?

EB: I read an interview you did with the Guardian in which you say: “I think writing always gives us control over the things that we can’t actually control in our lives.” Was there something in particular you were writing towards controlling or understanding in Ayiti?

RG: In Ayiti, I simply wanted to write about and convey the multiplicity of the Haitian diaspora experience. All too often in the American media, Haiti is only discussed in one narrow, limiting way. I wanted to offer something that is, I hope, different.

EB: In “Of Ghosts and Shadows” two Haitian women have a private romantic relationship: “For now, we are women who don’t exist. We are less than shadows, more than ghosts” because to be in love with another woman is an “American thing” which is stigmatized and even dangerous. How do you think desire becomes something dangerous, or a tool for other-ing? Do you think desire is (problematically, so) something some people have to be able to identify with in order to sanction?

RG: Desire becomes something dangerous when people outside of that desire don’t understand it. People are, generally, terrified of things they do not understand. Desire is not something people have to be able to identify with in order to sanction but unfortunately, many people in this world have not gotten that message.

In “Ayiti,” I wanted to write about and convey the multiplicity of the Haitian diaspora experience. All too often in the American media, Haiti is only discussed in one narrow, limiting way.

EB: Many of the stories in this collection carefully explore the experience of rape — the life that comes before and the life that happens after. I was often thinking about your introduction to Not That Bad: Dispatches from Rape Culture where you write about the evolution of that anthology as “a place for people to give voice to their experiences, a place for people to share how bad this all is, a place for people to identify the ways they have been marked by rape culture.” I wonder, with the re-release of Ayiti in the same year, do you envision Ayiti as being part of that conversation?

RG: Hmmm… Only one story in this collection, “Sweet on the Tongue,” explores the experience of rape so I honestly don’t know what you mean here. I suppose I’d ask you why you think many of these stories explore the experience of rape? That’s a strange takeaway for this book.

EB: That’s fair! There is only one story that deals with the direct experience and after-effects of rape, but I noticed the threat of sexual violence loomed over some of the other stories, too — for example, “In the Manner of Water or Light” and “The Harder They Come.” For me, that stood out as something that reflected the way the reality and possibility of sexual violence influences women’s lives. But these stories are also about celebrating sex and intimacy as triumph, so it’s certainly too reductive to say they’re “about rape” except to the degree that sexual violence informs women’s experience in general. Given the fact that Ayiti was re-released in the same year Not That Bad came out, I was just wondering if you saw the two books as being in conversation with one another at all.

RG: I did not write “In the Manner of Water or Light” or “The Harder They Come” with the idea that there was the threat of sexual violence in them but alas, I cannot control what readers perceive… In both stories, the sexual encounters are consensual. I don’t see Not That Bad and Ayiti in conversation beyond that they both largely center women’s experiences.

Short fiction is an ideal medium for bringing to bear the horrifying reality of our present moment. It allows the comfort of distance provided by fiction but also allows an unbearable intimacy of painful truths.

EB: In many of the stories, there’s a battle between a Haitian insistence that to have enough is enough, and the American urge towards excess that begins to drown out everything else. Many of the characters in the collection note: “We are defined by what we are not and what we do not have.” Can you talk more about this?

RG: As I got older and began to understand the economic disparities in Haiti and the resilience of Haitian people, I also came to understand the difference between how Haitians and how Americans consume, well, everything.

EB: The stories in this collection occur in between Haiti and America, and carry a similar refrain of “What You Need to Know” which often ends in correcting the patronizing caricature of life in Haiti produced by CNN and other news networks. In an opinion piece for The New York Times back in January of this year, you wrote that you were “tired of comfortable lies” that give us permission to ignore the truth that “no one is coming to save us from Trump’s racism.” Instead, you suggest, we need to learn to “sit with it, wrap ourselves in the sorrow, distress and humiliation of it.” I wonder, do you think story helps us sit with the sorrow, distress, and humiliation in ways that news can’t?

RG: I do think story helps us sit with difficult things. Oftentimes, the news is overwhelming and let’s be honest, it is an entertainment product that pretends it is not an entertainment product. It is this constant refrain, often repetitive, and it is easy to become inured to the news. With a story, it’s generally going to be something new and different and insightful. The story is a less chaotic space than the news. Stories should entertain but we know that up front. We enter into discourse with story in a more honest manner and, I think, we receive what a story says the same way.