essays

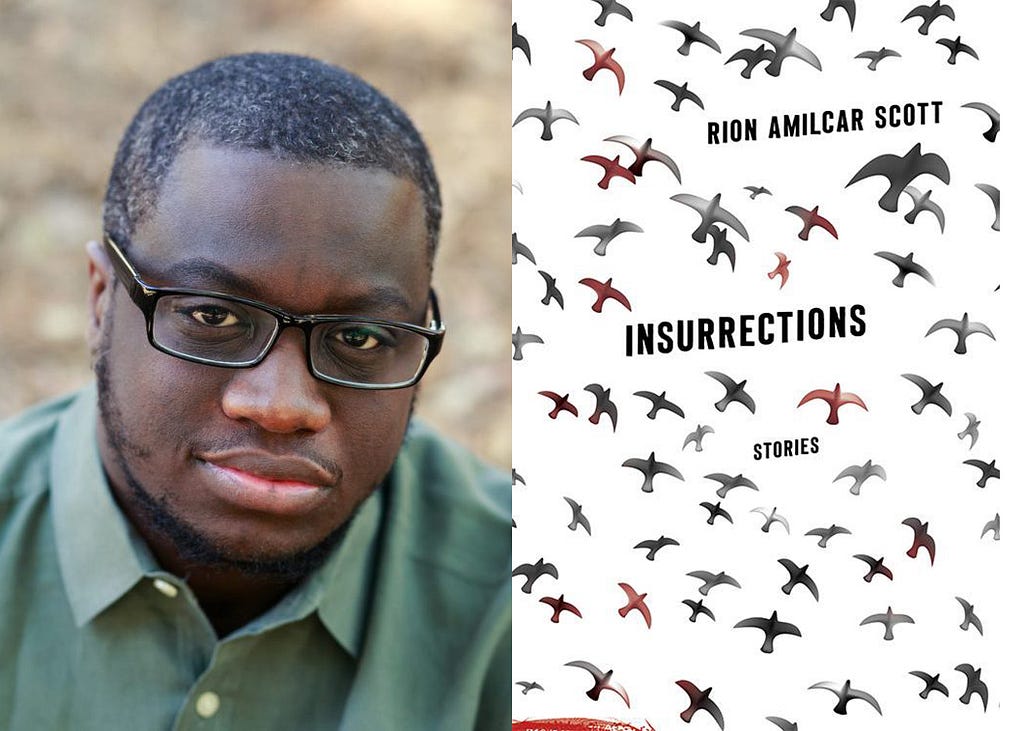

Screening Room: Rion Amilcar Scott on Big Bird, Writing, Adulthood, and the Unfairness of Death

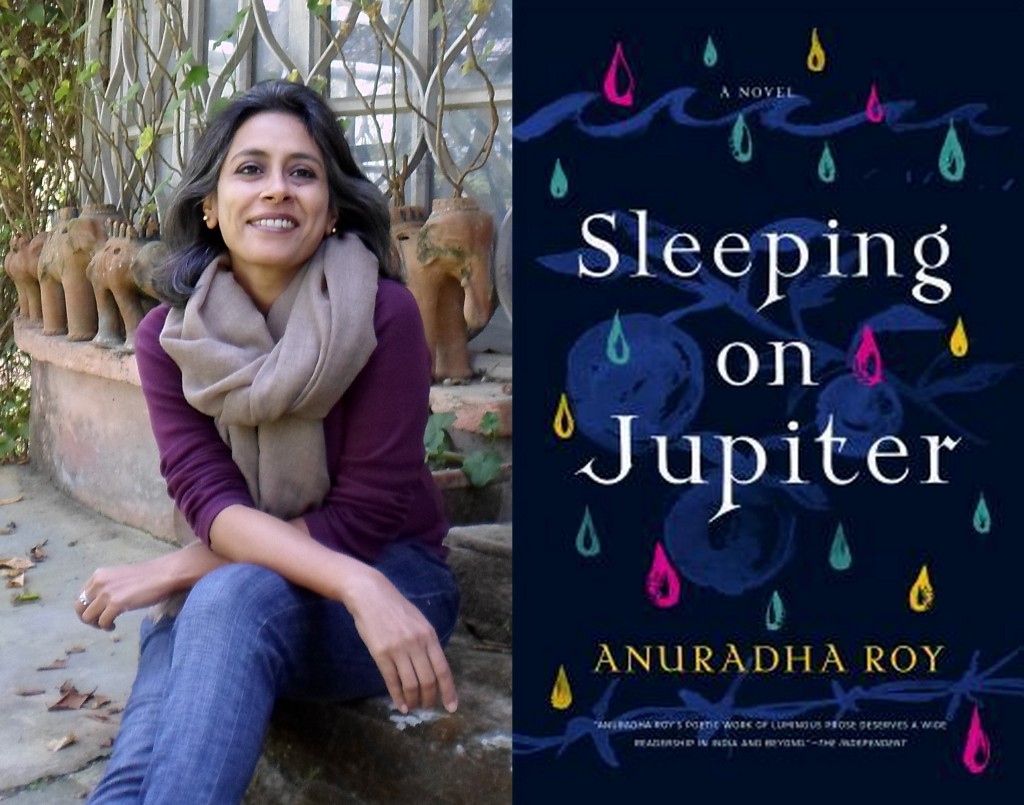

The author of ‘Insurrections’ on one of his filmic sources of inspiration.

I used to joke that between apparel, toys, books and DVDs, my family was, for a time, single-handedly funding Sesame Workshop, the non-profit that produces Sesame Street.

I had always been fascinated by Jim Henson’s gentle philosophical method and by the visionary Id-like wildness of his puppets. My toddler — himself an agent of chaos, akin to so many of Henson’s greatest creations — provided the perfect excuse to finally study at close range the antics of Henson’s Muppet characters. There was another reason of course, the great unpleasant present that often numbed me and left me cold: the low bank balances and high fees for existence; the sameness of each workday and fleetingness of each weekend; the damn maddening frustration of constantly having to be the disciplinarian — how bad I was at all of this. And the paperwork. No one tells you about the paperwork that adulthood involves.

Like so many others, I longed for childhood’s simplicity. I longed for the brown television in my grandmother’s bedroom, with its old-fashioned knobs and antennae, and how we had to carefully tune those knobs to clear the static from the PBS stations, which Granny and I would do enthusiastically every weekday in order to watch Sesame Street.

For my son’s third birthday I purchased a DVD set, Sesame Street Old School Vol. 3: 1979–1984. The set happened to encompass the span from the year I was born until, roughly, the last year Granny and I watched the show regularly. Around the time of his birthday I was drafting what would become the first story in my published collection, Insurrections. Initially I’d called the story “The Party” (in the collection it’s retitled “Good Times”), as it involved a Cookie Monster-themed birthday party thrown in honor of a rowdy toddler. In real life, the Cookie Monster party we’d thrown the year before when my son turned two had been a great success. In fictional form, however, it was transformed into a disaster. The father, who has survived a suicide attempt, plots the party as a kind of redemption, but nearly ruins everything by purchasing and wearing a foul-smelling Muppet costume.

By the time I’d given my son the Old School DVD, I had thought my story was finished. After slipping the disc into the machine, Samaadi and I began to watch it during dinner one night when I was struck by something incredible. Will Lee, the actor who’d played the gentle grocery store owner Mr. Hooper had passed away one season. Instead of ignoring his death, the Sesame Street writers had chosen to incorporate it into the show. As the human characters sit around discussing politics and other such pedestrian grown-up things, Big Bird arrives holding portraits he’s drawn of each of them in pencil. The adults are delighted, but when he shows them his drawing of Mr. Hooper they suddenly grow quiet, contemplative.

I can’t wait until he sees it, Big Bird says. Where is he? I want to give it to him.

Big Bird, don’t you remember we told you? Mr. Hooper died, Maria says. He’s dead.

Oh yeah, I remember, Big Bird replies. I’ll give it to him when he comes back.

Big Bird grows increasingly agitated and upset as the adults patiently explain that Mr. Hooper is not coming back. The actor who plays Bob breaks into real tears as he tells Big Bird they should all be grateful for the time they got to spend with Mr. Hooper. Big Bird rages at the unfairness of death — Give me one good reason! he cries.

In the end he realizes that all we’re left with is our sadness and our memories, and that there is no alternative “good reason.” As Gordon tells him, it has to be this way just because.

The scene is heavy, but never dark. Painful, but beautiful. And incredibly human in the way the actors publicly work through their grief, before the cameras, for the benefit of children everywhere. They didn’t have to do that. No one would have blamed Sesame Street for not addressing Mr. Hooper’s sudden absence. The choice to grapple with it face-on is more than anyone could have reasonably expected, but they did it. Children’s television elevated to high art.

I watched with wet eyes, nearly forgetting the three-year-old child next to me. When I looked at him he was sitting wide-eyed, riveted, barely lifting his fork to put food into his mouth.

Do you understand what’s happening? I asked him.

Yeah, he replied, looking solemnly at the screen. Mr. Hooper went to the store.

We returned to our silent, sad viewing. I tried to conjure the words needed to further explain, to help him understand. The words escaped me, and so, after a few minutes, I asked him again if he understood what was going on.

Big Bird is sad because Mr. Hooper is lost, he said.

Do you think he’s coming back?

No, Samaadi said. He’s lost. He’s not coming back.

Many thoughts and emotions passed through me as we watched, “Goodbye Mr. Hooper.” I didn’t have to contend much with death as a child; my grandmother didn’t pass until I was well into adulthood. I didn’t need to rage then like Big Bird. I viewed it as sad, but not unfair. Granny died at 101. I got to be with her longer than most. She had to die because we all do. Just because. But I did, and do, rage foolishly at the passing of time, the growing complexity of life that I can scarcely make sense of most of the time. Eventually the simplicity promised by childhood is like the adults told Big Bird — it’s gone, it’s lost, it’s not coming back. The only place I’ve found that small offering of peace is in writing fiction.

Watching Sesame Street with my son, I couldn’t help but think of my story of the suicidal father, hoping and grasping for Sesame Street to make sense of his unbearable life. I began to see images of him playing the episode for his son, for different — and yet related — reasons than I had played it for my own. I knew then that the story I had assumed was finished still needed more work. And I realized this only because the show that taught me letters and numbers, the show that helped teach me to read, continued teaching me as an adult to feel.

Rion Amilcar Scott’s work has been published in journals such as The Kenyon Review, Crab Orchard Review, PANK, The Rumpus, Fiction International, The Washington City Paper, The Toast, Akashic Books, Melville House and Confrontation, among others. His debut short story collection, Insurrections (University Press of Kentucky), was published in August 2016. Find him at: http://www.rionamilcarscott.com.