interviews

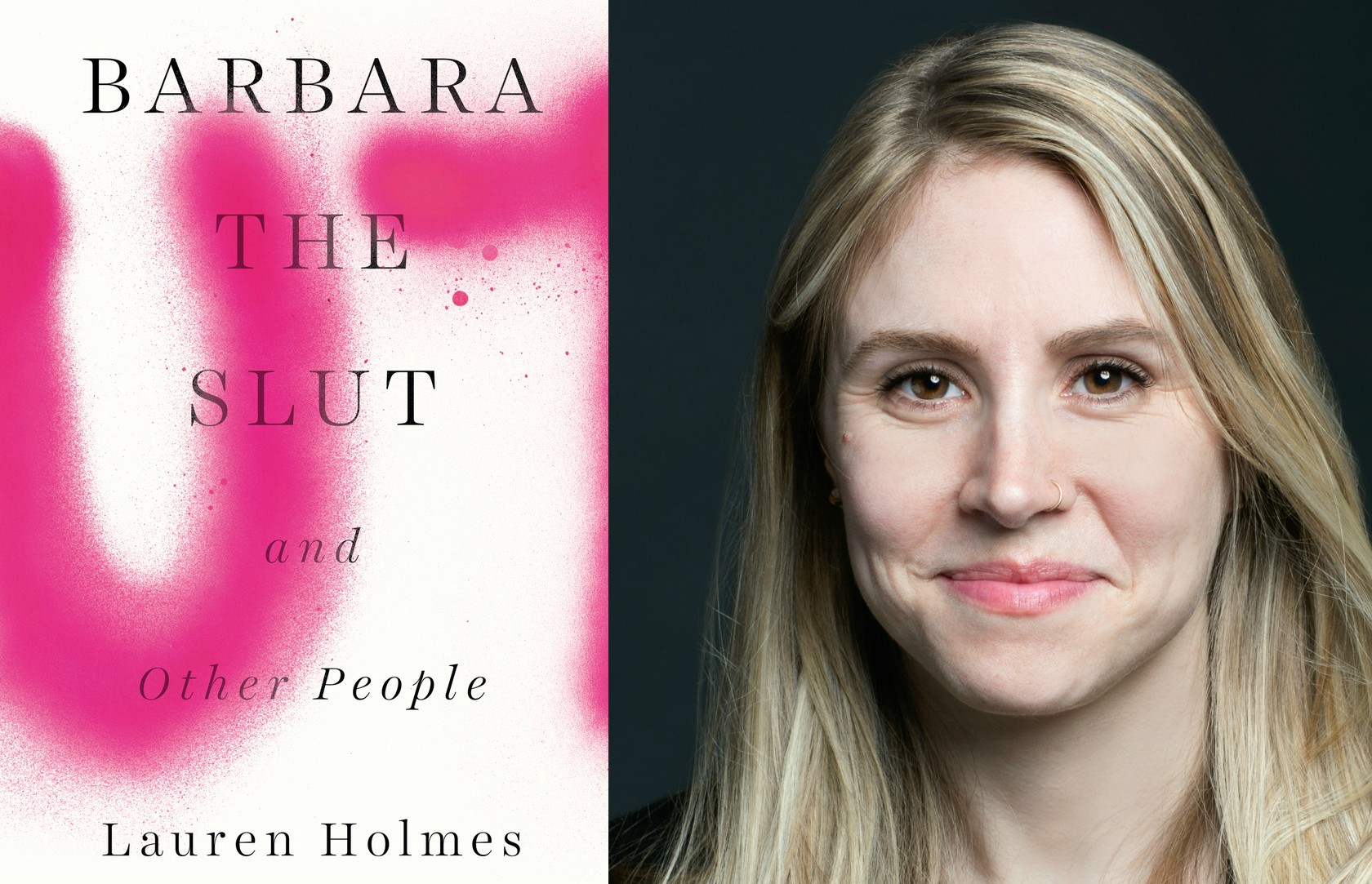

Seeing In A Haze Of Vulnerability: An Interview With Lauren Holmes, Author Of Barbara The Slut: And…

S

The urge to label people, emotions, and the minutiae of our everyday experiences was born way before the hashtag. Yet there’s something strikingly millennial about the characters who people Lauren Holmes’ much-praised debut Barbara The Slut: And Other People (Riverhead Books 2015). This is not to say that the alarming authenticity of these stories uses the “Selfie Generation” as a device. No, these are merely people trying to sell the American Dream in the fallout of the nuclear family. The collection, which I read feverishly in one sitting, made me think about the chasm between who I am and the person people perceive me to be, and how even in my most vulnerable moments, I can’t be sure I’m honest with myself. Saturated in the honey of sex and ridicule, these stories take us to task for our obsession with the erotic power in everyday life. I talked with Holmes about her debut and about what it’s like to be a millennial woman who writes about sex — or is, at the very least perceived as one.

Jill Di Donato: Though there are some sex scenes in the collection, what I find most compelling is your descriptions of what characters are thinking during foreplay and sex. You really work the subtle observations; your depiction rings so honest. How, as a writer, do you convey that specific type of vulnerability?

Lauren Holmes: Thanks! I love awkward shit, and pay close attention whenever that type of vulnerability is present in my own life or in someone else’s life, either in the real world or in the fictional world of a book, TV show, or movie. Any vulnerability I write is inspired by feelings I’ve felt or witnessed.

JD: I also feel like this book sends the message that there’s a thin line between shame and vulnerability. How do you see the relationship between those two feelings?

LH: I think vulnerability can come from fear of shame. Both vulnerability and shame are such inevitable and universal parts of the human condition. And that’s what I wanted to say by exploring these feelings in my stories — everybody feels these things, they’re unavoidable, they’re human, they’re important, and they’re okay.

JD: Moving from feelings to words, we Americans have a rich history of using words as weapons, to dehumanize and disenfranchise people. I’m thinking particularly of the word “slut,” which is spray-painted across your book jacket. In your opinion, why do words have this effect on people?

LH: Words are fucking powerful. I’m sure there are exhaustive explanations for why words have the effect that they do, but to me, the enormous and dangerous power of words is a basic fact of humanity.

JD: The word slut has come to mean, in my opinion anyway, a catchall insult for a woman that’s representative of a larger cultural mistrust of female power. What do you think about the word slut?

LH: Well said. I agree. “Slut” is such a powerful word because the shame we assign to female sexuality is so powerful. “Woman who has sex” shouldn’t be an insult, but of course it is. And you’re right, now “slut” seems like it’s becoming one of many bad words for “woman.” But that generalized usage doesn’t soften the original meaning and power of the word. I keep talking about this example — college baseball player Joey Casselberry calling 13-year-old baseball player Mo’ne Davis a slut earlier this year. He tweeted: “Disney is making a movie about Mo’ne Davis? WHAT A JOKE. That slut got rocked by Nevada.” What better demonstration of feeling threatened by female power than an adult white man calling a young black girl a slut? That power dynamic could hardly be more skewed. And he absolutely sexualizes her with that word, which is so fucked up on so many levels. Brittney Cooper wrote an important piece about this and about the sexualization of black girls for Salon, “Black girls’ sexual burden: Why Mo’ne Davis was really called a ‘slut.’”

JD: Is there a way to use the word “slut” in a sex-positive way?

Sorry to be a downer, but it’s hard to imagine that Americans will stop shaming women for their sexuality in my lifetime — I think it’s too deep a part of our culture.

LH: Maybe. But I don’t know what it is. Sorry to be a downer, but it’s hard to imagine that Americans will stop shaming women for their sexuality in my lifetime — I think it’s too deep a part of our culture. And until we do stop shaming women for their sexuality, I don’t know how we can reclaim the word “slut” or use it in a sex-positive way. But I do see so many amazing women owning their sexuality and refusing to be ashamed, both publicly and privately, and that gives me hope that we will eventually get where we’re going.

JD: Although sexual identity does not completely define us, it vastly defines who we are and how we relate to others in the world. In what ways do you feel this collection is speaking back to the canon of literature that takes on sexual identity?

LH: I wanted to represent sexual identity and gender identity in the here and now. One aspect of that meant writing queer characters the way I would write any other character–as a whole, complex person whose sexuality is only a part of their story, not their whole story.

JD: Without giving too much away, the image of Barbara envisioning herself as Cleopatra is breathtaking. How do you write a good sex scene? What are you trying to capture when you write sex scenes?

LH: I’m trying to capture sex as a regular part of life — as something ordinary instead of extraordinary. I got good advice to keep it minimal when it comes to sex scenes, since I was aiming for literary fiction, not a one-handed read. I see minimalism as a way to maximize the reader’s involvement and use of their imagination. Readers will fill in whatever they want or can, according to what’s meaningful (or titillating) to them. My goal as a writer is to not get in their way.

JD: Who are some of your favorite characters in this collection, the characters who stuck with you the longest?

LH: I can’t say I have a favorite, but Barbara was with me for a long time. I worked on that story on and off for over five years, and got used to having her around.

JD: What’s your process for creating characters like? Is it different depending on the character?

…when I’m ready to use the characters they suddenly and magically seem like whole humans (or dogs).

LH: Sometimes it seems like my characters are magically created in my subconscious, but what actually happens is that I think about my stories and my characters for a long time before I start writing, and when I’m ready to use the characters they suddenly and magically seem like whole humans (or dogs). I do develop them further in the writing and revising process, and sometimes I stop to write a character sketch if I feel like I need to get more of a grip on who a character is (that sketch is usually just a list of things I already know or need to know about them — their backstory, relationships, personality traits, and what motivates them — what they want and don’t want).

JD: Did you write the story “Barbara the Slut” first and did the other people (stories) follow?

LH: I think “Barbara the Slut” was the second or third story I wrote for the collection. But that story really shaped what came after it — once I decided it was going to be the title story, everything else had to fit into a collection called “Barbara the Slut.”

JD: How did this collection come together? How did it become a book? When did you know these stories added up to a collection, or did you set out to write a collection from the get-go?

LH: I set out to write a collection from the get-go. I couldn’t necessarily articulate how the stories were going to fit together, but I knew they would, because I wasn’t going for diversity — I was going for a focused examination of my world and my obsessions: coming of age, family, relationships, modern sexual politics, and loneliness and our search for connection.

JD: This collection is not only erotic (why is just reading the phrase “she told me to lick her pussy” so damn titillating?) but also, the book is really funny. Any advice on writing humor? Are you sitting there laughing to yourself, being like, yes! This is hilarious.***Also, please answer why you think your readers (ok, this one anyway) can get so turned on by reading the phrase “she told me to lick her pussy.”

LH: Thanks! I’m superstitious when it comes to writing humor — I feel like I’ll lose my ability to be funny if I try too hard to understand what it means to be funny. When I’m writing, I have no idea what’s going to be funny and what’s not. I’m pretty much never sitting there laughing to myself. Or if I am, and think I made the most hilarious joke ever, it ends up not funny at all and I have to cut it. And then things that I didn’t intend to be funny, people laugh at.

On that note and on the beauty of subjectivity, I would bet that for every reader who gets turned on by “she told me to lick her pussy,” another reader is offended and wants their money back. I’m thrilled that it worked for you, though.

JD: Especially with such a well-received debut, what’s it been like being in the literary world as a woman who writes about sex?

Male writers who write the same number of words or percentage of words about sex as I do are just considered writers, not men who write about sex.

LH: I think it’s interesting that I’m “a woman who writes about sex.” Male writers who write the same number of words or percentage of words about sex as I do are just considered writers, not men who write about sex. People keep talking about how my book is about sex, but other than the title referencing sex, I’m not sure that it’s any more about sex than any other piece of contemporary American fiction. And it might be less.

JD: Writing “first-rate short fiction” is like striking gold. What’s your process for writing a short story?

LH: I usually start with something small — the idea of underwear smuggling, the idea of a woman saying she’s a lesbian to get a job at a sex toy store — and build from there. Most of the construction happens in my head before I write anything down — I think out the story and the characters, and when I’m ready I start to write what I have. I continue the cycle of thinking and writing until I have a first draft, and then I revise the shit out of the story for ever and ever.

JD: At what point, when you’re writing, does the last line of the story come to you?

LH: I write so many drafts that I couldn’t say when the last line shows up — at some point it’s just there. And in most cases I revise the last line many times, so the final last line isn’t there until the end of the revision process.

JD: We both went to all-female colleges — you, Wellesley, me Barnard. What were your college days like? To me, that time is sacred. I really think those four years studying predominantly with all women made me more of a confident person. I’m not saying I’d be shier as a student with men in the classroom, but just knowing that a place just for women existed, and that I could chose to learn in that environment was very profound. What were your Wellesley days like?

LH: Honestly, my Wellesley days were tough. I had a hard time finding my way, and a hard time making friends. That was a nasty surprise after having a great time in high school, and having everyone say, “Just wait until you get to college!” A couple of weeks before I was supposed to return to Wellesley for my sophomore year, I realized I wasn’t even considering going back. Instead I kept working at Blockbuster, and then went to Mexico for two months, where I tried to learn Spanish and traveled around. That trip restored my faith in myself, and in my ability to connect to other people. I went back to Wellesley in the spring intending to transfer, but my grades were so bad I didn’t get into the other schools I applied to. That turned out to be extremely lucky, because I hit my stride at Wellesley my junior year. I found a lifelong mentor in Alicia Erian, who made me a writer, and found many other champions in the English department and beyond — professors who made me feel like I was definitely in the right place. I did manage to make a few friends, but mostly I decided to focus on my education and my extracurriculars. Of course, as soon as I decided that, I got involved in all the lesbian drama on campus, which was so annoying at the time, but such good training in conflict.

JD: There’s such heated debate about getting an MFA. You got one at Hunter, as a Hertog teaching fellow. I also got one at Columbia as a teaching fellow — which I always feel inclined to tell people so they don’t judge me for spending so much money on an MFA, and, well, not being a best-selling author. What are your thoughts on this debate — it’s almost like MFA-shaming. At the same time, people who are academically-inclined, are dedicated to improving their craft, and want to meet like-minded people, an MFA seems like a logical choice. What did you learn from getting your MFA?

LH: No kidding. I’ll admit that I had my doubts about the creative writing MFA — I questioned the need for the rising numbers of programs, and the fact that the programs were producing many more graduates than would ever be able to find work as writers. But then I realized that’s no different than any other MFA or other arts training — visual art, music, drama, dance. So now I’m not sure why there’s shame in doing a creative writing MFA and not in training for other arts. I mean, I can guess, but I still don’t think it’s worthy of such heated debate. Lots of people study acting and voice, and we don’t shame them for pursuing unlikely dreams.

I am endlessly, infinitely grateful for my MFA experience at Hunter. I learned how to write fiction there. I honed my voice and my style there. And I found lifelong mentors, readers, and friends. I feel so honored to have been a part of that program, and really, to still be a part of that program.

JD: Do you have any advice for aspiring writers considering the degree?

LH: Read Augusten Burroughs’s essay, “How to Follow Your Dreams Or Maybe Not” in his book, This Is How. (You can also find it on Psychology Today under “How to Ditch a Dream,” but if you don’t buy or read books, you should definitely not be allowed to pursue writing). After you read that essay and search your whole damn soul, if you still want to pursue an MFA, my advice is to do research. Research the programs you’re considering in any way you can — read their website, their students’ work, their professors’ work. Spend your time, energy, and money applying to the programs that seem like the best match for you, and that you feel a connection to. Wanting to go to a program because someone ranked it some magic number, or because it’s in a city where your ex-girlfriend lives and maybe if you go there she will take you back, those aren’t good reasons to apply.