Books & Culture

Sex, Drugs and Decaying Bodies

A Mexican novelist pushes the boundaries of post-apocalyptic fiction

It’s been nearly ten years since Roberto Bolaño’s epic Mexico City novel, The Savage Detectives, was published in English translation. It was a generation defining novel, the story of vagabond poets traversing the great federal city during the tumultuous 1970’s. The novel, translated into English by Natasha Wimmer, became a translation sensation, launching Bolaño into Gabriel Garcia Marquez-like lore.

Bolaño wasn’t Mexican by birth, and lived the latter part of his life in Spain and yet his shadow continues to loom large over Mexican fiction, and depictions of Mexico City. Bolaño and his Mexican contemporaries, who wrote about and lived in D.F. during the post-boom years, (including Carmen Boullosa, Daniel Sada and Juan Villoro) were themselves a bridge from the previous golden generation of Mexico’s Nobel literature laureate, Octavio Paz.

“We tend to see literature as cyclical, generational. And so it is. Like humanity, literature comes and goes in waves.”

Long the center of Latin America’s literature and art, mid to late century Mexico City was a place where writers and intellectuals sought refuge from the violent conflicts that ravaged central and south America — the reverberations of which are still being felt today.

We tend to see literature as cyclical, generational. And so it is. Like humanity, literature comes and goes in waves. Now, a new generation of Mexican novelists born in the 70’s and 80’s, and led by the recent astronomical success of Valeria Luiselli (Sidewalks; Faces in the Crowd; The Story of My Teeth; all published by Coffee House Press) has turned its gaze to the vast metropolis of 20 million people.

In the Transmigration of Bodies by Yuri Herrera (translated by Lisa Dillman) we’re taken into the depths of D.F. during a mysterious pandemic. As a fixer of sorts, the protagonist, known as the Redeemer, ranges back and forth across an unnamed capital city brokering a peace between two rival families, the Castros and Fonsecas — each holding the child of the other hostage. The book is written in the vein of Frank Miller’s tale of crime and underworld, Sin City, and tinged with classic, yet ironic, Shakespearian tragedy (one of the hostages is even called Romeo.

“[W]ritten in the vein of Frank Miller’s tale of crime and underworld, Sin City, and tinged with classic, yet ironic, Shakespearian tragedy.”

The city streets are nearly empty as the story begins. “For the past four days the message had been Stay calm, everybody calm, this is not a big deal.” Of course it is and it isn’t.

The Redeemer lives in the Big House, where he lusts after a neighbor, Three Times Blond, whose boyfriend won’t go outside during the epidemic to visit her. The Redeemer swoops in.

“This might be the last woman I’m ever with in my life, he said to himself. He said that every time because like all men, he couldn’t get enough and because, like all men, he was convinced he deserved to get laid one more time before he died.”

As the story proceeds we are introduced to many other characters — Neeyanderthal, the Unruly, Dolphin — few introduced by their proper name, adding to the dystopian feel of the tale. The Redeemer, with his muscle Neeyanderthal, goes back and forth organizing the exchange of hostages, but ultimately what is exchanged are their corpses. Romeo Fonseca was taken of his own asking, hit by a van and helped by the Castro brothers, out at the same nightclub. But the Fonsecas didn’t know this and kidnapped Baby Girl Castro, who dies from the mysterious epidemic, when they hear from witnesses that the Castros were seen putting Romeo into their car. It was, as the Redeemer says to Mrs. Castro, “A tragedy with no one to blame.”

Above all, Transmigrations is a character examination of the Redeemer, a story of how a man gets caught between two worlds. The Redeemer talks of his “black dog”, a presence he feels, like the hair pricking on the back of one’s neck, when a moral stand, a test occurs. He failed his first test as a kid in the barrio growing up, when a group of thugs beat up and carried off an already destroyed man. And since then, the black dog has haunted him.

“He learned to live with the cur, at times even to conjure him. […]His black dog was a dark mass that allowed him to do certain things, to not feel certain things, he was physical, as real as a bone you don’t know you have until it’s almost jutting through your skin.”

Herrera is best known for his novel Signs Preceding the End of the World a borderland story of going north and the grit of cartel violence. Transmigrations takes a different tack on that modern and yet distinctly Narco theme. Herrera’s Redeemer moves into and out of the drug-laced bordello and night club scene with it’s “juniors”, the sons of Mexico’s business and political elite, who live with the impunity provided by their family names. It is a land where no one is clean, nothing what it appears.

Mexico City has long been a safe zone where the cartel land violence rarely reached. But with the return of the long ruling, autocratic PRI party, under President Enrique Peña Nieto, drug violence has slowly but steadily crept into Mexico City. The recent, excellent Interior Circuits, by the journalist and novelist Francisco Goldman, digs deep into this phenomenon that Transmigrations hints toward.

To walk the long Reforma avenue, tuck into the many bookstores that line Mexico City’s famous Zocalo square, or happen upon a crowded, midday lit reading in the Palacio de Belles Artes — is to realize that Mexican literature is indeed thriving both at home and in translation.

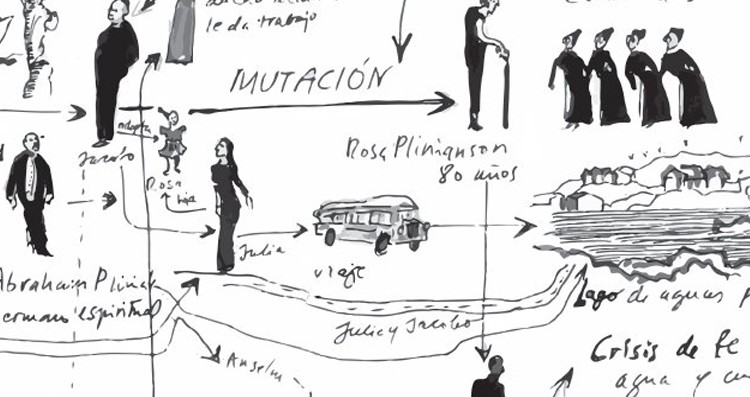

Even more exceptional novels, set in and inspired by Mexico City, like Transmigrations (and the recent, excellent Among Strange Victims by Daniel Saldaña París) are on the horizon: I’ll Sell You a Dog by Juan Pablo Villalobos (And Other Stories) this August and Laia Jufresa’s Umami(Oneworld) this September — and next year Empty Set (Coffee House) by the groundbreaking visual artist Verónica Gerber Bicecci.