Books & Culture

Sometimes a Dirty Photo Is Also Photographing Love: a Dispatch from the Kinsey Institute Library

by Ander Monson

Ander Monson’s interest in libraries extends beyond books to the human ephemera found in archives — evidence of previous readers and researchers and archivists among the actual holdings themselves. In July, he visited the world-renowned Kinsey Institute’s library in Bloomington, IN as a Coffee House Press In The Stacks writer-in-residence, continuing his exploration of the physical relationship between a reader and a book in an archive that includes not only the papers of Dr. Alfred Kinsey, but also books, print materials, film and video, fine art, artifacts, and photography related to human investigations of sexual behavior, gender, and reproduction. You can read an interview between Monson and librarians from the Kinsey Institute Library here. Below is part one of a two part dispatch from his residency.

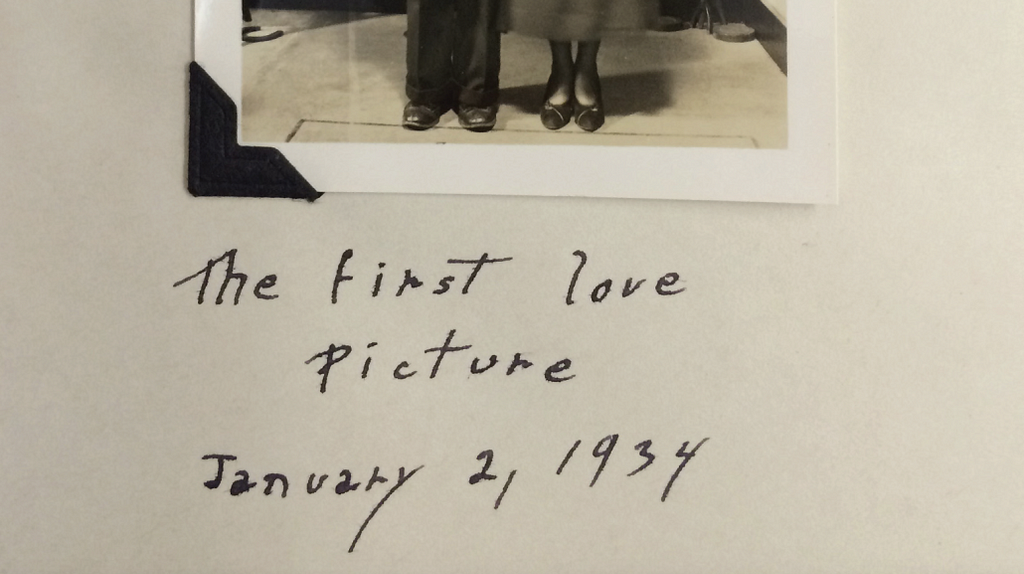

The First Love Picture

— Anonymous Photo Albums KI-AA:87 and 88 (Kinsey Institute Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana)

It’s a rush to follow this love’s course photographically from 1934 to 1953: courtship to foreplay to marriage to sex to baby to sex to tenth anniversary to sex to yet more sex and then beyond. These two amateur photo albums picture Peg & Bob, mostly on their own, mostly nude, and in equal measure, but with plenty together in sexual positions that you know by now from life or porn. They both seem to enjoy the naked posing game. The books and the cameras used are Bob’s. That’s his hand above; he narrates and curates both volumes, though Peg’s handwriting shows up halfway through volume 2. It’s Bob’s version of the story that is preserved, but who’s he speaking to? His later self? Their daughter Juniper? To memory? Since by now he’s gone, he speaks to me, if unintentionally.

I don’t know why their story ends suddenly with 56 pages remaining in the second book. The last full spread shows a naked Peg, annotated thus: “This is the way that she looked on September 9, 1952. What a wild time she had, and a fun time. It excites me a lot to look at this picture and think the thoughts that go with it.” Then we turn the page and see just frames without their photographs. One is captioned “my lover.” The next is captionless. The third: “Mr. D says, ‘Come and get me’” (you may guess that “Mr. D” is Bob’s nickname for his dick), but no photograph. Then two Polaroids dated August 1953, but they’re stuck together, face to face, and though by this time I badly want to know I won’t dare tear what has been so fused asunder.

Instead I check the back: it reads 037253. If I lift the flap I can barely see that one is a shot of a naked Peg, but how much she shows I cannot tell. By now we’ve seen it all. We know her body well — and his: the rhythm of the book suggests the facing photo is a naked Bob. Four assorted Polaroids come after, unmounted and unordered, none as interesting or technically accomplished as the ones before, then: blank page, blank page, blank page, blank page, blank, repeat.

So I hypothesize: Cancer took her shortly after. Or divorce. He strayed. Or she did, though she stayed. She tired of games and refused to pose. He got bored and petulant. One or both was disfigured in an accident and no longer wanted to be photographed, uncomfortable as they were with being seen as something less than what they were before. Or their lives became too full for things like this. Their love just ended or could no longer be contained in a picture. Or or or or or.

Every object has a story. Naked amateurs especially. Decades later Bob donated these books anonymously to the Kinsey, a librarian tells me (she recognized him later in another context and asked just to confirm). What might this have meant for him? Sure, anonymous thousands volunteered their sexual histories for Kinsey’s studies, and quite a few wrote to him afterward to amend the record, add more sexual encounters, admit to those they overlooked or made up and wanted to be sure were counted in the weeks or years after their initial interviews. Kinsey got his share of letters from the obsessives and the cranks (a red sticker denotes these in his correspondence) or those in search of a confessor, a professor, a colleague, or a lover. But for Bob to offer up something so obviously a love labor, intimate and individual, to the collection tells me something else. Was his donation like a publication? Did its accession validate the work? In being so collected and cataloged does it become art?

At the least it’s evidence. All libraries are filled with it, but the Kinsey’s something special: secrets and taboo and anonymity amplify the stakes. Sometimes when we make a dirty photo — not always, perhaps not even often — we are also photographing love. It’s this love I leave here with: a naked Peg fused face-to-face to a naked Bob, facing only each other, even if by accident. Of all these instances this is their only truly private joining.

Maybe it’s enough to know they’re here together, and that the Kinsey Library will keep them that way forever.