Craft

Somewhere on the Path Towards Self-Awareness: An Interview with Jen Beagin

by Melissa Ragsdale

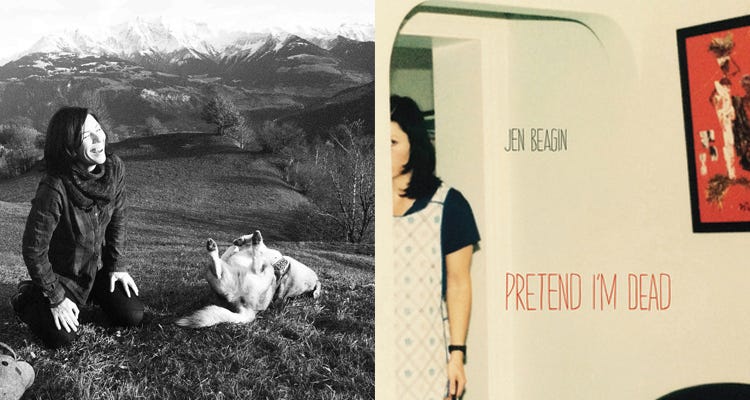

“Hole” (excerpted from Jen Beagin’s Pretend I’m Dead) is featured in Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading with an introduction from Emily Gould. Pretend I’m Dead is available from TriQuarterly Books.

Melissa Ragsdale: One of the most striking features of Pretend I’m Dead is the stark Mona-ness of Mona: she has this frank, strange, lovable flair to her that is all her own, from her nosy imagination to her habit of calling God “Bob.” Following the recent Claire Vaye Watkins “On Pandering” essay, there has been a lot of buzz lately about audience, voice, and where it comes from. How did you find Mona’s voice? Do you see your own self in her?

Jen Beagin: Oh, definitely. Mona is a version of me, for sure, except I’m much better looking. Just kidding. We’re about equal in the looks department. I do have slightly better taste in men and vacuums, but not much, and I did a lot more drugs, but overall, Mona is lonelier, and also more assertive, than I was at her age. I had a younger brother from whom I was estranged for several years and then reunited, and also a couple of besties, so I doubt I would have moved to New Mexico alone at that stage in my life–I was too attached to other people, and I didn’t have my shit together enough. In fact, I don’t think I had a bank account until I was 25.

In terms of the Watkins essay, I think that, for better or worse, I was pandering to myself at age 19, which was when I first attempted to write fiction, as a studio art major at UMass Lowell. It was also when I first wrote about someone named Mr. Disgusting. This was–yikes–over twenty years ago now. I ended up dropping out of college a year or so later and pulling a geographic to Santa Cruz, CA, where I cleaned houses and lived with my brother, and I didn’t write fiction again for 17 years. So, when I revisited Mr. Disgusting as a character, well over a decade later, I was very conscious of watching, and writing toward, my nineteen year old self. My aim was to write something she would have appreciated and admired, or at least wouldn’t be too embarrassed by. Watkins mentions “the little white man deep inside all of us” and, for me–at age nineteen–the little white men were mostly dirtbags, drunks, and addicts: Burroughs, Bukowski, Carver, a spoken word artist named Steven Jesse Bernstein, and, weirdly, Updike, who probably wasn’t a dirtbag, at least not in the same way, and whose characters I definitely couldn’t relate to, but boy, could he write a sentence.

MR: Addiction, recovery, and cleansing are huge themes of this book. Most of the characters are hanging onto something–whether a drug addiction or an event from their past–and many are engaged in elaborate stop-gaps. (For instance, Betty’s constant attempts to psychically spy on Johnny.) What does recovery mean for you? Do you see any of your characters as fully recovered?

JB: I don’t see myself, or any of my characters, as fully recovered, but rather somewhere on the path towards self-awareness. I was badly out of focus for many years, and by that I mean my primary focus was on other people and what they thought of me and/or the terrible things they’d said or done to me. Put another way, my head was always up someone else’s ass. Recovery, for me, starts with becoming aware of my own triggers, motivations, and fucked-up behavior, and I think most of my characters are on a similar path. Betty, though, is perhaps not very far along.

MR: One of the central points of this book is Mona’s move to New Mexico, and Mr. Disgusting ascribes great importance to New Mexico. What draws you to New Mexico as a setting?

I was a cleaning lady in New Mexico just before I went back to college in my mid-thirties. I didn’t live there for very long–I went broke after eight months–and I don’t feel as though I know the place all that well, but when I started writing, I knew I would set something there. Mostly, it was the landscape that spoke to me–it’s really dirty and really clean at the same time, and also both alive and dead, peaceful and unsettling, and I’ve always been drawn to those extremes.

MR: In this excerpt, we see Mona’s intense relationship with Mr. Disgusting play out, and eventually Mona begins seeing him in shifting perspectives between “aging hipster” and “total creature.” How did you go about creating this duality in Mr. Disgusting’s character?

JB: Mr. Disgusting is a composite of a bunch of guys I hung around out with in my twenties, all of whom were simultaneously young and old, beautiful and hideous, funny and dead serious. So the duality of Disgusting wasn’t something I felt I needed to create; it was already there, and very attractive to me.

MR: Mona’s relationship with photography is in flux throughout this book. While she’s under the influence of Mr. Disgusting, she blows off art school, and when she tells clients that she’s a photographer, she describes it as a “lie” to make them more comfortable with a white cleaning woman. Yet, we see that she’s both prolific and gifted at photography. For you, how much is Mona deluding herself? What does it take to label yourself as an artist?

JB: I took hundreds of pictures of myself cleaning houses, one of which was used for the cover of the book, because I was bored out of my mind, but I was also interested in making meaning out of the work I was doing. I cleaned a lot of houses all over the place, in Santa Cruz, San Francisco, and Taos, but I didn’t have much going on otherwise, and I wanted all the cleaning to count for something, even if it was “just for my records.” The pictures I took were mostly terrible or else vaguely creepy, and not in a good way, but I felt like I was doing something “other than,” which was vital to my sanity at the time. But was I an artist? Is Mona? I have no idea. I’ve always disliked that word. We are both photographers, though, for sure, and obsessive documenters.

MR: We see that Mr. Disgusting has a lot of power over Mona. However, in many aspects of his life, he is not in control–he’s a heroin addict, in failing health, close to impotent, and poor. In your view, where does Mr. Disgusting’s influence over Mona come from?

JB: Attraction is often a mystery to me, but I know that Mona feels invisible in her daily life and she feels seen by Disgusting, at least initially, and that’s very powerful. It doesn’t matter that he’s toothless, dickless, and penniless, because well-adjusted, well-heeled, conventionally handsome men don’t hold much interest for her. Yoko and Yoko would say that she manifested him for a reason, that he was the perfect vehicle for her to start dealing with her past, and blah, blah, but she also feels emotionally met by him on a level she hadn’t found with boys her own age, boys who perhaps hadn’t suffered enough. I remember being very attached to my suffering at that age, and also being drawn to people who had suffered in a similar manner.

***

Jen Beagin holds an MFA in Creative Writing from UC Irvine and has published stories in Juked and Faultline, among other journals and literary magazines. She lives in Boston. Pretend I’m Dead is her first novel.