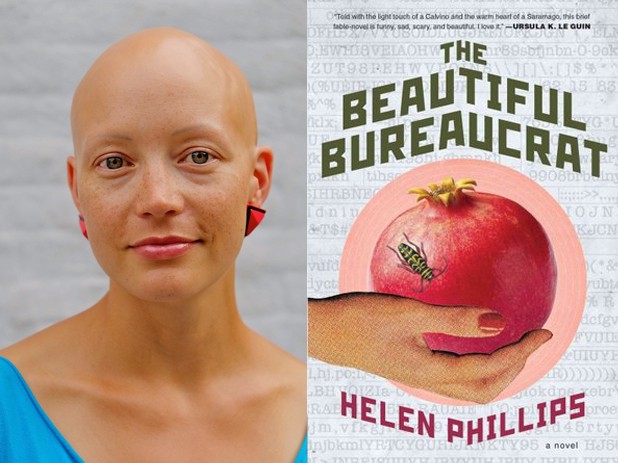

Advice

Structure vs. Urgency: The Blunt Instrument on Finding Work/Life Balance as a Writer

The Blunt Instrument is a monthly advice column for writers. If you need tough advice for a writing problem, send your question to blunt@electricliterature.com.

Hey Elisa —

I’ve had a lot of questions swirling since I decided to leave the MFA program I was at back in late November. Since I was a sophomore in college, all I ever really wanted to do was read and write. I didn’t really know where this passion came from, since, as a kid, I was a football-playing, church-going type of person who didn’t care at all about books. Once I got bit, though, that was all I seemed to care about.

That said, getting into the MFA seemed sort of like a dream. Something I really built up in my mind, which in retrospect couldn’t possibly have lived up to the hype. After sort of being away from the whole literary world for half a year, I’ve been able to see things clearer, and a few things really stick out to me about my experience that I’d love to get your thoughts on.

1) The literary community: One thing I really dealt with was taking seriously the literary community I had around me. To be honest, so much of what we were doing in the classroom seemed a bit overwrought and unnecessary. Like, much of the discussion about poetry seemed to be a great thing to us, but really useless in its larger context. Maybe this is just me being young and naive, but what is the true function of the literary community? How should it operate — both in the classroom and in the world — and what good can come from us truly investing in it? I know some of these answers will be obvious, but I also have a feeling there will be some answers I’m not quite expecting.

2) How to get back on one’s feet: Since I left the program, I’ve had to find a balance between my work life and my writing life. I have had to deal with leaving my ideal world of reading/writing all day, and have been forced to balance the daily grind of a job with writing, which is what I really want to do. I think my biggest fear is that, in leaving the MFA (ungracefully) at a young age, I’ve sort of squandered any chance I had at being able to truly give myself to my writing. I know this is a circumstantial thing, but how should one deal with the feeling that they sort of gave up on themselves and their dreams? What advice would you give to someone who is still young, but also feels like they sold out in this way? What hope is left for the one who quit, but still wants to pursue that thing they gave up on?

This is some of what I’ve been dealing with for the past year. In my mind, these things are connected, and once made whole again, might help me to become the writer I’ve always wanted to be.

— Trip

Trip,

I’ll start with your first question, which I think stems from a misunderstanding of what “community” is. Your MFA classmates are not necessarily your community. (I’m reminded of Junot Diaz’s essay about the whiteness of his program at Cornell, “MFA vs. POC.” They were definitely not his community.) Getting into an MFA program can be an excellent way of finding a writing community, but it’s not an instant community.

Remember your freshman year in college, how you probably made a few friends right away, but they weren’t necessarily still your friends by the time you graduated? When you’re meeting a lot of people at once (moving to a new city or starting a new job, for example), it can take a little while to find your people, the ones you really connect with, feel close to, and want to know better. The same is true with an MFA, and it’s entirely possible that you left the program before you had the chance to find the community that would have made your experience more worthwhile. (I don’t say this to make you feel guilty about leaving; I’m sure there were other factors at play, including cost.)

Further, I’ll say that the frustrating, “overwrought and unnecessary” nonsense that inevitably goes on in workshops is part of the point. A big part of the education of a writer is figuring out what you do and do not care about — including what kinds of readers are helpful to your editing/revision process, what kinds of critiques motivate you, what forms and techniques are interesting and generative and worth trying and what kinds are a waste of time, what kinds of writers you admire and want to emulate, and so on. (And if you intend to teach after getting your degree, it can also help you figure out what kind of workshop you want to run.) It’s actually helpful to be exposed to viewpoints you totally disagree with; most likely, not all of them are wrong. And by the time you finish an MFA, you have a more developed sense of what is worth your effort and attention as a writer and what is simply irrelevant bullshit. (That said, if your MFA experience is nothing but bullshit, quitting is a valid solution.)

But getting back to the idea of community and its function. I wrote about this in my first column, but allow me to reiterate: Your writing community serves an amazing dual function — they are friends who also help your career. (You’re helping them too, so it’s not parasitic.) They help your career both indirectly (through encouragement and friendly competition) and directly (by passing on opportunities and potentially even publishing you). But don’t underestimate the friendship part: A community gives you people to borrow books from, go to readings with, and talk to when you’re feeling discouraged. Seeing other writers get discouraged too will make you feel less alone. If you didn’t find a community at your program, I urge you to keep looking. Feeling part of an online community is almost (arguably just) as good. Writing can be very isolating without it.

Now let’s look at the second part of your question. You feel that you squandered an opportunity to read and write all day. Don’t beat yourself up about this. Quitting your program does not mean that you have given up on writing. You can always enter another program — but regardless, an MFA gives you two to three years tops of dedicated reading and writing time. Chances are slim that your degree will land you a job that allows you to make a living through writing (at least not the kind of writing you’re passionate about). It’s not long before you have to contend with the same struggle you face now: Finding time and energy to read and write on top of a full-time job. Excepting a very few especially lucky/wealthy people, every writer I know has the same struggle.

Again: you 100% do not need an MFA to count as a writer. All you have to do to be a writer is write. So how do you get back to writing? I’ll recommend two different approaches to striking a work-life/writing-life balance. I believe one of these can work for you, but which one works best will depend on your writing/working personality.

The first approach is driven by structure: Build regular writing and reading time into your schedule and stick to it, like it’s a regular appointment. I know a poet (with a full-time communications job and two kids) who gets up at 5:30 every weekday morning and spends an hour on poetry. This poet usually starts the hour by reading, and eventually does some writing. Maybe your writing hour takes place in the evenings, or it’s just 20 minutes a day, or a four-hour block on Saturday mornings. It doesn’t matter, so long as it becomes a habit. The advantage to this method is that, over time, you’re getting something done, plain and simple. Even if you have bad days or miss a few “appointments,” you won’t suddenly find that months have gone by during which you’ve written nothing because you “couldn’t find the time.” Aside from giving you material, this approach also trains you to take your writing seriously. You will feel like a writer because you’ll be writing. (Important to note, however, that just because you’re writing every day doesn’t mean you need to publish everything you write.)

As an addendum, you can help the structured approach along if you try to find a form that suits your structure. The fictional poet who narrates Nicholson Baker’s The Anthologist starts a poem by thinking about the best moment of his day. This sounds cheesy, but I kind of love it. (Conversely you could start with the worst moment of your day?) When I took a job as a copywriter for a software company about six years ago, I found that, because I was writing prose all day, I had difficulty “thinking” in poetic lines. So I started writing a book of prose instead. I consciously chose a form that fit the pattern of my days.

The second approach is driven by urgency: Find the thing you want to write so much you don’t even have to schedule time for it. I have another friend, a novelist, who said he solved the problem of “writer’s block” by abandoning the high-minded projects he felt he should be working on and started writing the novel he desperately wanted to write. Suddenly he couldn’t wait to get home from his job to work on his novel. Previously, he had had to schedule time for writing and it still felt like a slog. I take a similar approach to reading — I surround myself with books (mostly from the library) and abandon them freely. If I force myself to finish a book just because I’ve started it, I’ll find something to do other than reading, but if I only read what I really want to read, when I want to read it, I’ll make time for reading almost every day.

In closing: I have found that it’s very tricky to change your outlook by force of will. Almost no one can just decide, “I’m going to stop feeling like a sellout and start feeling good about writing.” The best way to change how you feel is to change what you do. Figure out what, and who, makes you feel good about writing, then strategically carve out more time for doing those things and being with those people.

Best of luck,

The Blunt Instrument