Lit Mags

Supernova

by Dani Shapiro, recommended by Electric Literature

EDITOR’S NOTE by Benjamin Samuel

I recently had the opportunity to hear Dani Shapiro read at the release of her new book Still Writing. I showed up late to a cramped bookstore and found myself standing awkwardly in the center aisle — the only one standing, in fact, except for Dani — as she read to us about the great “human catastrophe” of daily life. Our triumphs and failures, our embarrassments and celebrations, both grand and mundane, Dani explained, are all equally important and all rich fodder for fiction. And that’s exactly what fascinates me about her story “Supernova,” its focus on the minor catastrophe that is Shenkman, a relatively prosperous man whose minor shortcomings feel, to him alone, monumental and impossible to overlook.

As can be said for most of us, life for Shenkman isn’t going to be a marvel. “Everything about him was mid,” Dani writes, “midlife, mid-career, middling marriage.” At some point his promising life drifted off course and Shenkman found himself foundering amid the trappings and chattel of middle class suburban life. Shenkman has not failed, but he is still far from the success he might have been — which is, perhaps, even more humiliating. Perfection may be boring, and failure humiliating, but god save us from normalcy.

See, Shenkman’s prospects haven’t exploded around him, rather he’s just been something of a dud — fizzling out more or less unnoticed. Despite rowing everyday, obsessively racing against an old rival in a computerized simulation, nobody even knows Shenkman is still competing. Worse still, he isn’t even trying to win anymore, just trying to transpose his sense of defeat on anyone left in the race. Shenkman’s last hope for achieving something is his son, Waldo, who spends so much time stargazing, so disconnected from the real world, that he’s slipped out of Shenkman’s reach.

But if we can learn from our mistakes, if there is wisdom to be gained in failure, then Shenkman will at least have a legacy to leave behind to his son. And if Shenkman can teach us anything, it’s that sometimes the most we can hope for is that our children will have the chance to fail more spectacularly than we have.

“Supernova” is a story that succeeds because of its remarkable treatment of the mediocre, it’s focus on the middle of the pack where most of spend our days. It reminds us that we can exalt the quotidian, and that normalcy can be something to commemorate. As Dani writes in her essay “Ordinary Life,” “If I dismiss the ordinary — waiting for the special, the extreme, the extraordinary to happen — I may just miss my life.” Because most of the time existence doesn’t end with a bang or even a whimper, sometimes life ends with a shrug.

Benjamin Samuel

Co-Editor, Electric Literature

Supernova

Dani Shapiro

Share article

Shenkman pushes back with his legs, smooth and hard. Thinks of his old coach’s word: fluid. Hinges his upper body, then slides forward, arms extended. The briefest pause of recovery as the flywheel spins. Drive, recovery. Drive, recovery. He counts. One, two. Full lungs at the catch, empty at the finish. He gives the RowPro a quick glance. Fuck. 6K into this race and two sculls are ahead of him. On the wall, the flat screen displays the deep twilight blue of a lake. He is there, gliding along Lake Winnipesaukee, the ripples cast by his blades cutting down into the depths.

Alice is on the other side of the house, and Shenkman knows she’s lonely and slightly pissed off. These are the hours of the day when she expects him to be with her. To endlessly go over the only two or three subjects they ever seem to talk about any more: there’s her father’s macular degeneration and the question of who among her siblings will take on the job of getting his driver’s license revoked before he kills someone. Then there’s the onset of Shenkman’s mother’s dementia and its likely effect on their plans to travel over spring break. And finally, always, there’s Waldo, and the indecipherable results of one full day and three-grand worth of psychiatric testing to determine whether their son has a) the same strain of ADHD which seems to be going around the fourth grade like a virulent flu, or b) something else, something more, something for which Shenkman does not yet know the acronym, and for which he is unprepared.

One, two. His trapezius muscles burn.

It’s been almost an hour since he tucked Waldo in, but he knows his son isn’t sleeping. Every night, while Shenkman wails on the RowPro, while Alice sits in the kitchen sipping chardonnay, Waldo has been slipping out the back door. Shenkman knows this because he can see every open door and window on the burglar alarm monitor. The first time it happened (and the second, and third) he went to the window and watched Waldo tiptoe into the backyard with his iPad tucked under his arm. His dark hair, still wet from a post-dinner shower, shone in the moonlight as he settled himself on the ground against a fence post and tilted the iPad to the sky. He had begged Shenkman for an app called StarWalk, and now it’s all he’ll talk about. Instead of good morning, now Shenkman and Alice are greeted with reports of the day’s planetary action, complete with full description of the constellations visible in that night’s sky. Shenkman is hoping — God, he is hoping — that this is just a phase. He and Alice talk about it in a never-ending loop of parental, fear-induced justification. Remember the thing with the clocks? Waldo taught himself to tell time before he could even speak in sentences. Shenkman and Alice try not to notice the deepening furrows of worry, slowly becoming permanent in the face of the other, as if in time-lapse photography. What about the church bells? At this, they cannot help but laugh. When Waldo was three, they couldn’t drive past a church at five minutes before the hour, for fear that the bells would chime. Waldo would shakes his head no, no, no and bury his face in his arms like a little old man. It seemed cute, if a bit eccentric, at the time. From the RowPro, Shenkman sees the alarm pad blink.

Just-a-phase, just-a-phase, just-a-phase. His mantra on the machine. He has his nightly talk with himself. He promises himself he’ll be easier on Waldo. He hears the tone of his own voice, criticizing his son. What he really wants to say, what he means, is I love you and want the world for you. Instead, what comes out is more like Jesus will you stop picking at your fingers, or How many times must I tell you to stop humming at the dinner table? He finds his son unreadable, unreachable. This elusiveness, now at the center, the very heartbeat of his life, has begun to seep into everything. Shenkman wakes up in the morning with the feeling that the bed is tilted, the world slightly off its axis. He showers, eats breakfast, drives to work — but he’s not really present. The closest he ever gets is right here, in his mechanical scull, on his virtual lake. One, two.

Three hundred meters to go. On his RowPro screen, he’s now only four meters behind the leader. Lindgren, of course. Lindgren is edging him out, and eight others are trailing. Shenkman trained hard yesterday, sprinting and resting for a solid forty minutes. He overdid it, maybe. One, two. On the screen, it’s always a beautiful day, the sky a preternatural blue. A stand of trees shine like emeralds. His heart rate is higher than he likes, but he steps it up a notch. Pulls a hair’s breadth ahead of Lindgren. Fuck you, Lindgren. Fifty-eight meters left. Shenkman goes back to Winnipesaukee. Behind him, he pictures the buoys of the finish line, neon in the distance. In front of him, Lindgren, his wheat-colored hair whipping in the breeze. He hears the slap of his blades as they flatten against the water’s surface, then go vertical and slice silently down. He tells himself not to look at the monitor, think only of the finish.

He crosses it, panting. Sweat pours down his back. His heart hammers. Shenkman gives the screen a quick glance. The last remaining scull — that guy from New Zealand — slides to the finish line, and now all the sculls are lined up like perfect little soldiers. He rubs his stinging eyes with a towel, then squints at the bottom of the screen to see the winner. Lindgren. By an eighth of a second. Downstairs, the back door creaks open, then closes with an efficient click. Even if Shenkman didn’t have the twitching ears of a Labrador when it comes to Waldo, he would know from the alarm pad, which blinks once more. What nine-year-old leaves his own house late at night? His nine-year-old, that’s who. In his Red Sox pajamas, he is making his solitary climb back to bed. He will fall asleep with the iPad next to his head on the pillow.

The gym was completed last winter, three months behind schedule. Shenkman spent twice his bonus, maxing out a couple of credit cards in a shameful frenzy about which Alice is still in the dark. Shenkman figures, he pays the bills and what she doesn’t know won’t hurt her. He thought he’d have made up the difference by now, and though it hasn’t exactly worked out that way, he doesn’t regret one dollar spent on the sprung hardwood floors, the mirrored wall, the flat screen, the recessed lighting on dimmer switches. A man needs his sanctuary.

Except now there’s Lindgren. A lot of the guys have handles on RowPro. Names like oarsman291, or scullandbones. Shenkman himself is crewdude9. But Lindgren is just Lindgren. Shenkman had only been training for a few months when Lindgren popped up on the screen. The list of names, until then, had been an anonymized, digital blur. But then, late one night, as Shenkman was squeezing in a quick, ill-advised, post-prandial workout, a scull slid ahead of his, eased past as if on a different frequency altogether. Lindgren. Shenkman stared at the name. He started rowing harder. He gave it everything he had, his chicken lasagna dinner roiling in his gut. One, two. But he couldn’t catch up. When the race was over, Shenkman climbed off the RowPro, shaking, then vomited neatly into the wastepaper basket.

Since that night, he has been shaving seconds, then minutes, off his time. He’s almost there. Any day now, Lindgren is going to look down at his own screen and see that he has been surpassed. In fact, surpassing Lindgren has become Shenkman’s only goal. Not Shenkman winning, but Lindgren losing. He knows this isn’t a good way to be. That Alice wouldn’t approve. He himself doesn’t approve. But he has spent some time researching all things Lindgren — the reflexive Google fishing expedition has become something of a daily habit — and he feels that it is his responsibility to bring the guy down a notch.

He is in the process of stripping off his damp t-shirt and compression shorts when he hears a knock at the gym door.

“Hold on a minute!”

He grabs the thick, hooded terrycloth robe which hangs from its hook on the wall, like a prize fighter’s. No one ever bothers him in here. Alice boycotts the place; she sends in Esmerelda once a week to gather up his stinky clothes for the wash.

“Dad?”

Waldo stands in the doorway, his thin arms wrapped around himself. The iPad is nowhere to be seen.

“Wally, what’s the matter?” Shenkman still short of breath, and he hasn’t stopped sweating.

“Bad dream.”

Shenkman doesn’t point out that in the five minutes which have elapsed since Waldo’s let himself back into the house, there hasn’t been enough time to fall asleep, let alone dream a bad dream.

Be patient with the boy.

“Come.” He lowers himself onto a weight lifting bench, then taps the space next to him. Waldo approaches tentatively — Shenkman blames himself for his son’s reticence — then sits. Waldo picks at the edge of his thumb, already puckered and raw. He seems to be focused on a spot on the floor where the rubber mat has become dislodged, its edge curling up. The color in his pale cheeks is feverishly bright.

“What is it, Wally? What’d you dream?”

He shrugs his skinny shoulders. “Nothing.”

“Well, it can’t be nothing. You’re here now, aren’t you?”

The poor thumb makes its way to Waldo’s mouth. He has bitten the tortured skin nearly to the point of bleeding.

“You can tell me.”

“Hey, Dad?”

“Yeah, buddy?”

“Did you know — ” Waldo starts.

Shenkman steels himself. Any sentence from his son beginning with Did you know usually swerves far from the subject at hand.

“ — that Betelgeuse is a semi-regular variable star located approximately 640 light years from the Earth?”

“No,” Shenkman responds, a familiar heaviness settling over him. “I didn’t know that.”

“Yeah, and my app says it’s a red supergiant — one of the biggest stars known to — ”

Shenkman’s skin feels clammy. He’s getting chilled. All he wants to do is take a shower. “Listen, Wally — can we just — ”

“How about this?” The muscle beneath Waldo’s left eye twitches. “Astronomers believe that Betelgeuse is only a few million years old, and — ”

“Waldo!”

His tone — goddamnit, he’s been working on regulating his tone — comes out sharper than intended, and Waldo flinches a little, as if Shenkman had raised a hand to him. As if Shenkman would ever do such a thing.

Shenkman’s temper floats somewhere below his ribcage, a small boat on a stormy sea. He tries to breathe into it, meditates, almost, the way he has been training himself to do. He’s been reading up on this. He knows that his rage is just fear in disguise. That just beneath these sudden outbursts exists a love for his son so tender he can hardly bear it.

“I’m sorry.” He puts a hand on Waldo’s knee. “I’m sorry, buddy.”

“All I was going to say is that it may go supernova,” Waldo finishes dully. “Within the next millennium. That’s what the astronomers say.“

“I didn’t mean to startle you,” Shenkman says. “I only want to have a conversation. Can’t we just talk about something normal?”

Waldo turns and looks at him squarely. His eyes latch onto Shenkman’s and don’t let go. It’s my normal, those eyes say.

Back-to-bed-time. The digital clock reads 9:46, Shenkman notes with despair. The hours during which the pilot light in Shenkman’s brain, always burning, can finally be extinguished for the night — the hours in which Waldo is actually sleeping, gone under, arms flung wide, cheek pressed deep into the pillow, lips parted, nothing left to say or think or do — those hours are shrinking fast. Before he knows it, dawn’s thin light will creep through his bedroom window. Alice will be facing him, her eyes covered by a black sleep mask, small balls of wax stuffed deep into her ears. His feet will hit the tilted ground, and he will once again begin his day. He’ll get to the office early, scan the markets, initiate buys of stocks that got hammered the day before, looking for short-term bounce. Before lunch rolls around, he’ll check in with his half-dozen big clients, whose moods will reflect their portfolios. He will be battered or buoyant. Confident that he’s one centimeter further up the invisible ladder he always seems to be climbing, or worried that he’s in a slow motion free fall. He will send emails, reply to all, show up for the three o’clock teleconference with their satellite office in San Francisco, all the while carrying an awareness, wedged like a razor in his solar plexus, that if his son cannot grow up to have a successful life (not that the doctors have said this, as Alice keeps reminding him) then none of it matters.

“Come on, buddy, let’s give this sleep thing another try.” Shenkman slings an arm around Waldo.

“But I’m not tired.”

“Sure, you’re tired. You’re so tired you don’t even know you’re tired.”

He ushers Waldo out of the gym. It isn’t right, having his son here, as if something adult, something male and illicit takes place in this mirrored room. He leaves the lights on. After he tucks Waldo in, he’ll come back up here, shut down the equipment for the night.

The boy is snug beneath his American League quilt, his small body finally limp, as if someone had come along and flipped his off switch. Shenkman quietly makes his way down the hall, doing his damnedest to avoid any creaking floorboards. He’d rather not negotiate with Alice now, who is still in the kitchen, watching the ten o’clock news. In the morning, that bottle of chardonnay will likely be empty, deposited next to the trash for him to take out on his way to work.

He lets himself back into the gym, breathing in the sharp, familiar scent of his own rankness. His workout isn’t complete until he enters his time into the log, along with the name of the victor. Lindgren, he writes in ink, at the top of a column built entirely of only one name: Lindgren stacked upon Lindgren. A tower of Lindgrens. The symmetry is weirdly satisfying. Once again Shenkman is back on Winnipesaukee, rowing the Meredith Bay course. Lindgren in front of him, their movements as precise and aligned as a corps de ballet. Lindgren, for whom winning always came so easily that it meant nothing at all.

Shenkman hadn’t laid eyes on Lindgren since graduation. He skipped the big twenty-fifth reunion last May, though he did pore over the ensuing alumni magazine one Sunday morning on the can, examining the array of glossy pictures: balding men wearing madras ties, their guts spilling softly over the tops of their khakis; women with tamed blonde hair and tanned, leathery arms. Was it all going south from here? My god. What was their thirtieth going to look like? Or their thirty-fifth? He skimmed the class news: promotions, second marriages, cancers, late-in-life babies, career changes. It seemed this — this early midlife into which they had all been thrust — was the last possible moment for a course correction. Greg Adams had left his lucrative law practice in New York, and opened a fair trade coffee importing business in Burlington. Marshall Hughes and his second wife had just adopted a baby girl from China and set about getting her cleft palate fixed. Shenkman had been about to toss the magazine when he noticed a photo in the bottom right-hand corner. Lindgren on the beach. Lindgren, looking handsome, buffly prosperous in his faded t-shirt and Ray Bans. He was flanked by his undeniably hot wife and their two wheat-headed kids. Lindgren hadn’t provided his own class note, of course. The accompanying bit of information had been shared by Mindy Sessums, who had recently run into the Lindgren family in Westport, where Lindgren was planning to open the twelfth restaurant in his tapas empire.

Ever since that Sunday morning on the can, Lindgren grinning up at him from the magazine resting open between his knees, something had shifted inside Shenkman. If life was a race, then Lindgren was winning; he had pulled ahead of the pack, with his perfect progeny and his fortune built on $16 quartinos of Tempranillo and $20 small plates of jambon. He, Shenkman, had fallen somewhere into the baggy middle. Everything about him was mid: midlife, mid-career, middling marriage. It had happened slowly, but it was unmistakable. He hadn’t made good choices, he now understood. He’d like to slap his own, placid, stupid fucking face. His logic — if had he even employed logic — had been ass-backward. He’s made the grave error of being satisfied by the small stuff. The bonus check. The nice car. The right preschool. He’d thought he was moving forward, but he had been standing still. He had slipped behind without noticing.

Before he shuts down the gym for the night, Shenkman opens his laptop — he knows he shouldn’t, that no good can come of it, but he can’t help himself — and does a quick scan of Lindgren’s life. Nothing is really new. The same photos on Google images of Lindgren and his wife at black tie events that manage to look both expensive and bohemian. The same maximum contributions to Obama’s campaign. The same Facebook fan page with 7568 friends for an empire which extends from Scarsdale to Armonk to Greenwich to West Hartford. The newest addition — Palermo Soho Westport — is opening the very next night. According to Zagat’s, Lindgren has single-handedly brought the culture and flavor of Buenos Aires to New York City’s suburbs. There is hardly a neighborhood in Westchester or Connecticut from which one can’t make an easy drive to Palermo Soho. The restaurant group’s website displays a tasteful slideshow of Argentinian street life, accompanied by Gato Barbieri-esque saxophone. A perusal of Yelp turns up mostly positive feedback. Great service! Amazing wine selection! Five stars!

Shenkman lowers himself to the mat he keeps on the floor for the stretching exercises he’s supposed to do, then hunches over the keyboard. Leave a comment? Sure, he’d be delighted to leave a comment. He gives one star to Palermo Soho Scarsdale. He’d give zero stars, but that isn’t an option. Mediocre, he writes, then deletes. He can do better. Very disappointing, he types into the comment box. My wife and I expected better. This restaurant has a great hype machine — here he pauses, stopping to think of what might wound Lindgren, should Lindgren himself actually be scrolling through his own customer reviews — but it has no substance. He stops, pleased with himself. No substance. But before he hits the send button, he hesitates. He catches his own reflection in the gym’s mirror: a pale, slightly balding middle-aged guy sitting on the floor like a child in his thick white terrycloth robe; he looks away, ashamed. Is there any way — any possible way — that Lindgren can find out that he’s behind the comment? No, he decides. It’s impossible. Shenkman presses send, and nothing happens. Sign in and create an account? No, thanks. He presses send again. Nothing. This — even this anonymous bit of petty subterfuge — is beyond him.

The following evening, Shenkman flies out of work early. He’s been in a fog all day, finding the simplest transactions taxing, unable to keep up with the trading floor banter. He feels under the weather, almost. Like maybe he needs to go home and just get into bed. But once he’s in his car, dodging in and out of traffic on the FDR, his energy returns in a great wave, surging, uncontainable. He needs to keep moving. Smooth sailing up the Major Deegan. He tenses his thighs against the seat of his car, then releases. Rolls his shoulders. Grips the steering wheel so tightly his knuckles go white.

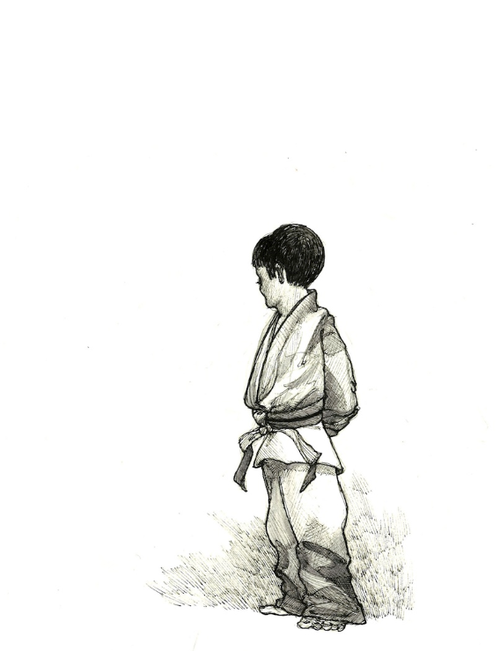

By the time he passes his usual exit on I-95, Shenkman’s mind has gone all buzzy. He tries to calm himself by listening to NPR, but there’s an interview of some kid he’s never heard of who’s just won the jury prize at Cannes for directing his first film. He switches stations, and now there’s an expert on celiac disease opining about the merits of a gluten-free diet. He pictures Lindgren at his grand opening. Judging from the picture in the alumni magazine, the guy looks even better than he did in college. Like life hasn’t touched him. He doesn’t have mounting credit card debt, or a blind but still-driving father-in-law, or a mother with dementia, or a disappointed wife, or a son whose future is uncertain. Shenkman cracks his knuckles. He’s not going to get home in time to take Waldo to his Jujitsu class. Not even close. He should probably pull over and call Alice, but he can’t stop. If he stops, he’ll lose momentum. If he stops, he’ll have to consider what he’s doing and where he’s going. Instead, he guns it.

Hey, Lindgren. How’s it going, Lindgren. Long time, Lindgren. His pulse races along with the car. He doesn’t know Westport well. It’s about forty minutes north. In fact, he isn’t really sure how to get there, and he can’t plug it into his nav system, not while the car is moving. Alice is going to be pissed. But she can take Waldo, just this once. On a straightaway, he steers with his knees and texts her. Working late. U ok to take W to Jujitsu?

The whooshy little blip of his outgoing text lifts his spirits. The highway unfurls like a black velvet ribbon wrapped around an unexpected gift. No Jujitsu. No standing with the other parents — he has nothing to say to them — while they watch their kids tumble and spar like a litter of preppy puppies. Waldo, the runt. Always on the margins. Waldo, who makes jokes the other boys don’t understand. It kills Shenkman, when the boys turn away from his son. He takes some small comfort in the fact that Waldo doesn’t seem to mind. But Shenkman minds. On the way home, he coaches Waldo: don’t stare at the ceiling like that. Stop pulling at your bottom lip. Don’t do that weird thing with your tongue.

By the time Shenkman gets off the highway and finds the Post Road in what he hopes is Westport, it’s dark. The downtown, such as it is, is deserted. Luxury chain stores closed for the night. He drives ten minutes — all the way to Norwalk — before he realizes he’s going in the wrong direction. Doubling back, he nearly rear-ends the car in front of him. Finally — just as he’s about to give up — he spots a tasteful sign for Palermo Soho Westport in an upscale strip mall off the main drag. It’s next to a cheese shop and salumeria, presumably also owned by Lindgren, with dried sausages, prosciutto and wheels of manchego sweating in the window. The ornate wooden doors of the restaurant are propped open with enormous ceramic planters. A few revelers in cocktail dresses and sports coats are sneaking smokes on the sidewalk.

Shenkman makes his approach. Each tall, fair-haired man he passes morphs for an instant into Lindgren. Shenkman’s heart thrums irregularly in his chest. He would know Lindgren better from behind. For two years, they were on the same boat. Lindgren, the stroke, was closest to the coxswain. His stroke set the pace. And Shenkman, rowing in the seven position, focused solely on Lindgren’s damp white t-shirt clinging to his back, those thick muscles, his ropey arms, hair whipping in the Winnipesaukee wind. Drive, release. Drive, release. Intent on the coxswain’s commands: Bow four, back it down! Number three, hands down and away! Timing his every stroke to Lindgren’s.

He wants only to say hello, he tells himself. To see up close the tangible result of a lifetime of good fortune. Because that’s what it is, he’s decided. Certain people — namely, Lindgren — get more than their fair share. Somewhere along the way, luck — or the lack thereof — becomes immutable. It hardens and calcifies like a diseased artery. He, Shenkman, is not lucky. Oh, he can work hard, do all right. He can eke something decent out of this life of his. But he’s not Lindgren. He can’t alter his position. It’s as fixed as the cosmos, and as predictable. He’s not, as Waldo would put it, ever going to go supernova. He’s just a garden variety bit of space rock.

He scans the crowd. A photographer is darting about, stopping certain people who pose and smile: a woman with excellent teeth; a man in a pink, open necked shirt with a white collar. In the cavernous dark of the restaurant, the camera flashes. The music is loud, heavy on the drumbeat. The banquettes are covered in faded red velvet, low tables scarred with candle drippings. Ornate chandeliers and sconces. The effect is of a place that already has a history, not one that is just opening today.

Shenkman’s heart knocks against his chest. His breath is labored. He finds a waiter, downs a glass of wine in three gulps, then takes another from the tray. He hasn’t eaten much today, and his gut instantly burns. He grabs a handful of marcona almonds from a small dish on the long, polished bar. The green glass chandeliers cast the party-goers faces in a ghoulish light. Behind the bar, the glassware sparkles.

The photographer’s flash is now lighting up a banquette in the far corner of the restaurant, and Shenkman knows — before even seeing, he knows — that it must Lindgren, who would never circulate at his own party. Of course he wouldn’t. It was the same way in college. Lindgren, his arm carelessly around some girl, who basked in her own chosenness. He always seemed to be laughing, a shark’s tooth dangling on a string around his neck.

His blackberry vibrates in his pocket. Alice has sent him a text: No worries. At dojo with boy. She has attached a photo to the text. He taps on it and Waldo fills the screen, tiny and barefoot in his stiff white uniform, flanked by two beefy kids. A yellow belt, the color of French’s Mustard, is wrapped twice around his narrow waist, marked with vertical black lines signifying progress towards the next color — orange, he thinks. These kids look like big, galoomphing oafs, their reddish faces offset Waldo’s pale visage like two garish bookends holding up an elegant pamphlet.

Something inside Shenkman swells. He pictures his boy, his old-man brow creased as he shouts the Japanese numerals: Ich Ni San Chi Go! The sensei has taken a liking to Waldo, who — despite his lack of coordination and general spaciness — has mastered an intricate set of Jujitsu commands. Shenkman takes another sip of his drink and tries to breathe. What the fuck is he doing? His boy deserves a father who can take measure of his life. A father who can grasp it all — the complexity, the failure, the imperfection — without ducking or feinting. Drive, recovery. Drive, recovery. All there is to it.

Fortified, he begins to snake his way through the tables and banquettes, until he arrives at the back of a very familiar head. Lindgren is sitting with his wife and kids. The shoulders still wide, longish hair curling against his soft, strong neck. The cuffs of his blue oxford shirt rolled up, exposing an athlete’s forearms. Snatches of conversation all around him: tomorrow at the beach; leather trench coat, if you can believe it; sitter’s day off.

He stands by the table and clears his throat. The banquette is U-shaped, and Lindgren’s back is still to him. He’s next to his very pretty wife, a hand resting on her knee. It’s she who looks up at Shenkman with the cool, practiced glance of a woman who’s used to people wanting things from her. She nudges her husband under the table, points her chin in Shenkman’s direction. On her other side, a girl and a boy, around Waldo’s age, are bent over an iPhone.

Lindgren turns around. The face is the same. A few crow’s feet at the corners of his eyes, but otherwise he is unchanged. Not so Shenkman, who is acutely aware of his balding temples, his sagging jowls, the permanent lines running across his forehead. Does he even look like the same person?

“Lindgren! It’s me!”

The wife leans over. “Hi, I’m Laurie Lindgren. And you are?”

Shenkman blurts out his own name. He watches as he comes into focus for Lindgren.

“Oh my god, buddy. I rowed crew with this guy,” Lindgren tells his wife and kids.

“Long time,” he manages.

“Come sit with us.”

“I don’t want to intrude — ”

“Don’t be silly.”

Shenkman lowers himself to the banquette next to Lindgren.

“Congratulations. You know, on your restaurants and all.”

“Thanks, dude.” Lindgren just keeps looking at him with a big grin. “God, I just can’t believe it! How the hell are you?”

“Good,” Shenkman gives a little shrug. He tries to smile. His face feels rubbery.

“So what are you up to? Married? Kids?”

Shenkman pulls his Blackberry out of his pocket and shows the screen to Lindgren.

“The one in the middle is my son, Waldo. He’s nine.”

“Hey, look at this, guys.”

Lindgren passes the Blackberry to his kids. They put down the game boy and look at the photo of Waldo. Ich Ni San Chi Go! The boy has Lindgren’s eyes, and is wearing a frayed rope bracelet — the kind of thing Lindgren might have once worn. These kids, who weren’t even specks of dust in the universe back when Shenkman stared enviously at their future father’s muscled back, his impressive arms, the aura of his own rightness glowing all around him. These kids — his too — whose future selves are as mysterious as distant galaxies. Anything can happen. Anything, right? Isn’t that what he used to believe?

Late last night, after his botched attempt at online restaurant criticism, Shenkman had stood for a long time in the doorway to Waldo’s room. Then he rearranged the quilt over his son’s sleeping body, bent down and brushed his lips against Waldo’s cheek. He lowered himself to a bean bag chair on the floor. His mind was full of a thousand questions: Why do you measure doorknobs? Why do you track hurricanes? Why do you check the clock every ten seconds? Why do you talk about constellations? Why? Why?

“Adorable. What’s he into?” Lindgren’s wife is asking.

“Jujitsu,” Shenkman says. “Astronomy. Time travel.”

“Sounds brilliant,” Lindgren says. “No surprise there. This guy — ”

Shenkman waves him off.

“No seriously — this guy was the wicked smart one. Always figured you’d be doing some crazy-ass thing with numbers, man.”

Lindgren’s daughter hands the Blackberry back to Shenkman. She’s a pretty girl, with an uncomplicated face. It would be easy to imagine her path through life. Its simple, burnished ease. For some reason, Shenkman sees arugula, watermelon, a martini glass with a single olive. His vision is fracturing, the room suddenly kaleidoscopic. Who knows? He knows nothing. Wicked smart. Waldo — of this much he is certain — Waldo breaks every mold. He may surprise them all with his strange, agile mind, his kinetic, unstoppable energy. He takes after nobody. Betelgeuse, he hears that soft voice. Red supergiant.

“You know, I’ve been rowing again,” Lindgren is saying. He leans forward, elbows on the table. “Got this machine called RowPro.”

“Yeah?”

“You might want to look into it.”

“I’ll do that.”

Shenkman pushes himself up from the table. He needs to go. Voices speak as if from a distance. Good to see you, buddy. Hey, thanks for stopping by. He’s moving swiftly now. He belongs in the dojo with his wife and son, cheering from the sidelines. The sensei is teaching Waldo throws and kicks and hold-downs. But there’s so much more he needs to learn. So much to prepare for. How to stand his ground. How to anticipate an incoming punch. How to bow to another with dignity, even grace. How to break a fall.