interviews

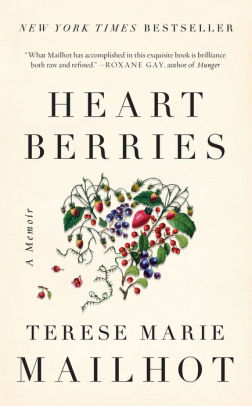

Terese Mailhot on How to Talk to Men, Children, and White People

The author of the memoir "Heart Berries" talks about what women and writers are too often forced to give

I read Terese Marie Mailhot’s memoir Heart Berries once, then read it twice again. In her book, Mailhot explores the traumas of her life: her impoverished upbringing on the Seabird Island Reservation, the loss of her eldest son in a custody battle, her fractured relationship with her future husband. When the author is hospitalized with a dual diagnosis of PTSD and bipolar II, she requests a notebook as a condition of treatment, and begins writing herself back to health. Mailhot and I spoke last week about the kinds of colonization she’s experienced in her writing career and life in general: what men take from women, what white society expects from other cultures, and why writers devour the insights of others.

Deirdre Sugiuchi: You describe Salish stories, stories told by speakers of the Salish tribes, as being sparse and interested in blank space. Can you describe how this is reflected in your art?

Terese Mailhot: Language is extremely important to us. Every word counts and cannot be convoluted. There’s a lot of power in trying to illustrate the truth of something. I had to render it in a really simple way.

DS: I’m obsessed with process, especially in regards to clarity. Do you have any specific methods to achieve clear prose?

TM: People think I’m experimental. I don’t really like that word. It’s really high-brow compared to what I do, which is strip all of the things that seem like unnecessary contrivance or bravado.

DS: You write from the perspective of a Native writer, but you also address the dominant culture. Can you discuss writing with this double consciousness?

TM: With the essay Indian Sick, I’m writing first to (my husband) Casey. It starts with desperation. Casey is a white man and was raised with some sense of normalcy. That whole essay is trying to navigate and impart the truth of my story to this man who can’t ever fully know the disparities between my circumstances — those of an Indian woman — and his. That letter became about something larger than Casey by the end. By the end it became about my father. I think in the beginning it was really important to bring Casey in and the only way I could do that was by explaining what he couldn’t understand.

I could not look at being Indian; I had to look through it.

It’s the one occasion I felt conflicted about using the second person and speaking to Casey, and a lot of that is the culture of me and everything that signifies why I feel so deeply about my world and the history of genocide that we are dealing with. I think that conflict is present there on the line level, but when I was writing the book, I had to place myself at the center of the story. I could not look at being Indian; I had to look through it.

The audience should always be with me and should never feel like I’m withholding my heart from them, but sometimes I’m not giving them the thing that maybe they expect. A lot of that was the resistance to an MFA aesthetic, a white MFA aesthetic of show don’t tell. There’s a lot of telling in the book.

DS: I never could do an MFA for that reason.

TM: Most are operating within a system of competition, of things that feel so anti-art, so degrading sometimes. They kind of shape you artistically into something that most of the time you are not, especially for people writing outside of old-establishment aesthetics.

DS: Several years ago I read this paper by Sandra Bloom called Bridging the Black Hole of Trauma: The Evolutionary Significance of the Arts which, among other things, addresses the ceremony of creating art in Native American culture. You are clear that your practice of ceremony differs from the tradition with which you were raised, but can you discuss how you use your writing practice as a healing ceremony?

I was less sick when I started purging the truth of what happened to me on the page.

TM: I think the book itself is like an incantation. There are aspects, especially in the latter part of the book, that feel like a spell that conjures my mother. When I read it out loud, especially the passages about my mother, it feels sacred and it feels powerful, and something happened when I started writing that made me feel like a human being and made me feel better about her.

I was able to write the explicit truths of what happened to me. I can’t even speak it, but I can write it. When I start reading the passages about how I was able to say one word “father,” then I was able to say two words, that was literal. I was learning the language of how my father hurt me. There was something about the physical act of writing that made it less visceral. I was less sick when I started purging the truth of what happened to me on the page. I became physically less anemic and I was more able to function in the world.

I think everyone should have that thing that illustrates the nature of themselves in a physical way.

DS: One of the themes in the book was you taking from men, conditioning them, and them taking from you. That list at the end, where you detail how you took back when you were hurt by men, was incredible.

TM: I didn’t know that was going to come. I knew I wanted to write about these things that had happened but I didn’t want to give those men characterization and their own pages. I didn’t want to illustrate all the bad interactions I’ve had with men, just to assert that men had maltreated me and my body and my spirit and my intellect. I listed them, and the way they hurt me, and how I reacted, and doing that without shame was important for me. Making it matter-of-fact was necessary.

DS: You begin by talking about taking from men, but at the end you realize that you have given away too much. Can you discuss how this is reflected in the culture at large, be it on the tribal or social level?

TM: I think straight women sometimes have to negotiate with themselves, asking, is this the best of all possible worlds with men? We’re mistreated so often and victimized so often that sometimes we put up with things we shouldn’t.

It was important to say I was put in a place of exploitation, where I was subjugated and objectified for my body, and then I just fought against that as much as I could, working within that system. I feel like that’s important for a lot of native women to hear: if you want something, to get it from the world however you want it, and I hope and pray that they find true independence from men, not that they are the worst people. There is something so profound in being able to buy yourself dinner and not having to rely on someone.

DS: Your grandmother was a crucial early figure in your life. She attended a reservation school where “parasites and nuns and priests contaminated generations of our people.” Can you discuss the impact of your grandmother going to the reservation school on your family and your culture?

I feel like resilience ascribes this value to certain types of survival that don’t interest me.

TM: Residential school has stripped many indigenous communities of their languages and communal practices and it’s difficult to talk about it because residential schools were mostly led by Christian missionaries and priests, so that has also infected the way we view ourselves as human beings. One thing Christianity gave people was shame. It’s not as if we didn’t have shame before colonization, it’s that shame operated differently. You didn’t need to be contrite. You had to be knowledgeable about the self and there is a distinction. My grandmother had to learn to survive in an environment that wanted to assimilate her into white life, white ways of knowledge and thinking and interacting with the world. After she attended residential school, she moved back to be with her people and she taught nursery and she helped kids. It felt tender to sit next to her and pray, but what wasn’t tender was that she cleaned maniacally. Everything had to be immaculate. The cleaner the environment, the closer you were to God. I would see her cleaning as if somebody was watching her and I remember distinctly thinking this is how she cleaned when the nuns were around.

She spent a long period in a tense environment like that where she was being monitored and shamed when she didn’t do the right thing, and I wonder what kind of grandmother she would have been outside of those parameters and experiences. There’s this thing of being beyond resilience. She was exceptional. I don’t know how I could have lived through what she lived through and have been so kind.

DS: In addition to exploring your childhood in your book, you also explore your relationship with your own children. You describe bonding with your son and nurturing your son even though you did not always have a nurturing relationship with your own mother. You say, “Children can be teachers too.” I know that having my own son impacted me and my connection to my work. How do you think your sons have influenced your art?

TM: They’re just better people than we are. Children are just better. Their job is to push you around and test you, and if you raise your voice, you’ve lost and they know that you’ve lost. When I had Isaiah I was dealing with postpartum depression, and I had subpar healthcare, and I was on my own, and I had just lost my first son. I found myself uncontrollably sad, and I needed help. There wasn’t any. So, I prayed for patience to hold my son, and look at him in the eyes, and not see the son who wasn’t there — or how they looked so much alike. I had to pray for the strength to do it alone. Once I started throwing myself into putting Isaiah first, everything fell into place, and I was able to love without fear. I stopped being scared I wasn’t good enough to be a mother.

I had to learn to love somebody when I felt like I was nothing. I was broke, and loving him wholly without considering losing him, it taught me something about love. He opened my heart in a way that nobody else could have. Nobody else could have made me so tender and human. Him needing me made me a better person. I feel like children do that to us if we answer the call. I feel like when you answer that call, you see how good the world can be.

DS: You discuss resilience in your book, particularly white attitudes about resilience. You say “It’s an Indian condition to be proud of survival but reluctant to call it resilience.”

TM: I don’t like the term. I don’t want to be known for my ability to survive because it’s like they are asking you to get over it as they are calling you resilient. It’s like I’m here smiling but if you were there crying would they still call you resilient? No. But are you still a survivor? Yes.

I feel like resilience ascribes this value to certain types of survival that don’t interest me.

DS: Because it devalues the people who don’t make it?

TM: I’m suspicious of most words people use to define Native people. I feel like it’s really interesting to examine the words they are using.

I always hear the term raw used to describe work by people of color, or by a woman who’s been abused. I’m suspicious of how they are using the word, although I don’t mind the word because I think I try to cultivate art that appears vulnerable. Plus, the idea of resilience is the idea of recovering quickly from something. I feel like, my god, we’re still in the midst of it. We’re not even out of the storm that is colonization.

DS: I read your essay where you discuss decolonizing your narrative as a Native writer. It made me wonder what it would be like if non-colonized people were examined the mindset of colonization thoroughly and regularly, even in today’s world, which is considered “post-colonial.”

TM: I think it’s so weird because a lot of times during workshop, even when I do fellowships, and when I go to this really nice place where there’s a lot of young writers and there’s a lot of older writers who are trying to finish their books, sometimes I’ll have a cohort, a friend who writes about their experiences and they come from a different culture, like Korea or India, and immediately the whole room, even the POC writers, will sometimes be like, “Wow you gave me some insight into the world of x.” That’s not a writer’s job. Our job is to make art. Was it good on its own merit? That’s what’s important to talk about. That to me feels like decolonization because people want to colonize work. They want the insight. They want the experience of it. They want to devour it and own it. Later, when they talk they want to be able to say, “Oh let me tell you this fun fact about x culture. I just read this essay.” I feel like that is a very western thing, to want to colonize the insight gained from experience, and know it and own it and possess it and then impart it to other people as an authority. I think it’s important for people to understand that my work is supposed to connect you to me as a human being and I want to be treated so afterwards, you know? Not as a cultural artifact.