interviews

An Experimental Novel About Malaysian Chinese Lives in the Aftermath of the May 13 Riots

Li Zi Shu's "The Age of Goodbyes," translated by YZ Chin, centers the struggles of Malaysian Chinese women through decades and generations

The Age of Goodbyes by Li Zi Shu, translated by YZ Chin, is a wild ride of a novel. It begins on page 513—a nod to the deadly race riots that broke out in Malaysia on May 13, 1969—and follows the ascent of Du Li An from her humble beginnings as the daughter of a street vendor into a formidable matriarch and boss-lady through her marriage to a wealthy, influential member of a Chinese gang society.

While May 13 is a significant date that has been impressed into the minds of every Malaysian (including this reader), no primer on Malaysian history or the Malaysian Chinese community is necessary to immerse yourself in the many worlds of The Age of Goodbyes. Zi Shu, an acclaimed, award-winning writer of Chinese literature, weaves a rich tapestry of the everyday lives of ordinary people in this mining town with the action-filled plot lines, romantic entanglements, and deft pacing of the Hong Kong television dramas that the characters themselves consume religiously.

The book is no less a daring feat of literary experimentation. Braided into Du Li An’s storyline are two Pale Fire-esque threads of meta-fiction involving a teenage boy who co-habitates a sleazy, rundown motel called the Mayflower with prostitutes who’ve seen better days, and a celebrated author who may or may not have written the very book you are reading. By the end, you, as a reader, can’t help but feel like you’ve been enlisted as a character of the novel as well.

I spoke with Zi Shu—her translator YZ Chin valiantly translating as we went along—over Zoom and live text. We talked about female friendships, the challenge of addressing Malaysia’s race relations in a novel, and Mahua literature.

May Zhee Lim: Reading this as a person who grew up in Malaysia, the characters’ backgrounds, their social dynamics, and their relationships felt very familiar to me. We always knew whose parents or neighbors had shadowy connections to mobster groups, just like Steely Bo and the Toa Pek Kong Society. Where did you draw your inspiration for these characters?

Li Zi Shu: I think many of the novel’s characters are drawn from my experience working as a journalist in Ipoh. I was a reporter for about eight years in my hometown of Ipoh. During that time, I had the opportunity to rub shoulders with locals from different socioeconomic backgrounds; I was able to observe their lives, their speech, and their mannerisms. Of course I knew my old stomping ground’s general atmosphere and environment like the back of my palm. All of these naturally surfaced when I wrote the novel. Sculpting these characters was actually the most effortless part of writing this book.

MZL: I think you also captured the gossipy nature of the Malaysian Chinese community. Everybody knew everybody’s business. It’s almost like the Greek chorus. Was that part fun to write?

LZS: Describing the daily lives of ordinary folk was definitely the most fun I had while writing the novel. I felt an especially strong kinship to Ipoh [the “fictional” mining town in the novel] when I was writing the parts featuring Du Li An. I had a chance to revisit the impressions and memories I had of my hometown, which then helped me better confront my relationship to my townspeople. With each character I sketched out, I grew to miss and “love” my home more.

MZL: The Age of Goodbyes was first published in 2010 and it has already won an award abroad but it was only translated into English and published by Feminist Press this year. How does it feel to finally introduce a novel you wrote more than twelve years ago to an English-speaking audience?

LZS: Twelve years ago, I was a young person who approached writing a full-length novel with burning ambition. That’s why I spent many years conceiving and completing The Age of Goodbyes. For a period after its publication, I felt proud of that accomplishment, though in my heart of hearts I still saw it as merely an exercise, a rehearsal. After all these years, I’ve come to develop many more ideas and aspirations for the novel genre so I’m no longer satisfied with the completion of this particular book. But as a Mahua writer, I remain very grateful that I can introduce the book to the English-reading world. I hope the novel draws a bigger readership and more attention to Mahua literature. I’m thankful for the enthusiastic efforts of translator YZ Chin. Without her, I probably wouldn’t have sought out translation opportunities, given my passive personality.

MZL: YZ, maybe you can speak to the translation and publication journey for this novel. How did this book come to be published? Who approached who?

YZ Chin: This book wouldn’t exist without writer and translator Jeremy Tiang. I approached them at a literary event because I greatly admired their novel State of Emergency. They planted the seed of an idea–namely, that I could and should translate. The more I thought about it, the more I found translation to be natural to my state of being. I’m sure you know what I mean. Growing up in Malaysia means being immersed in a multilingual environment. We don’t think twice about slipping between two, three, or four languages.

MZL: Yes, absolutely. It’s very effortless to switch between languages at the dinner table.

Growing up in Malaysia means being immersed in a multilingual environment. We don’t think twice about slipping between two, three, or four languages.

YZC: So thanks to roundabout introductions via Jeremy, I got in touch with Zi Shu on Facebook. I’d actually deactivated my account, but reactivated it just so I could talk to her. I’m fortunate that Zi Shu is so open and a dream to work with. We essentially hammered out the details for my translation over Facebook messenger, and then I pitched Feminist Press, the publisher of my first book, Though I Get Home, which is set mostly in Malaysia. I felt there was a foundation I could build upon to emphasize the importance of a book like The Age of Goodbyes, given FP’s mission to lift up marginalized voices from around the world. It was obviously a great fit for us.

MZL: I want to ask you more about the women in the book. I mentioned Elena Ferrante just now in our Zoom chat because there is something about the intense, complicated, and charged dynamics of female relationships in your novel that remind me of the Neapolitan novels. Can you talk more about this?

LZS: I grew up in an environment dominated by women. At home I only had sisters and no brothers. My father was never around. Later on I attended an all-girls secondary school. You could even say I grew up in a matriarchal world. I’ve always felt that the connections and friendships between women are more humorous and colorful than those between men. When you transpose all this into a fictional setting, dissecting these details and nuances layer by layer, you have more than enough to support an entire novel’s plot. When it comes to writing the world of women, there may not be epic quests or grand narratives with the fate of the universe in balance. But it’s possible to depict–from everyday life–heart-stopping scenes as full of conflict as any battlefield.

MZL: I totally agree. The scenes between women were some of the most memorable ones in the book for me. I was both really touched and saddened by the relationship between Du Li An and her best friend Guen Hou. Even their two decades of female friendship could not escape the subtle, casual, yet painful elements of sexism that the women, and the men, in our society have internalized. Sometimes, you convey all of this in just a single, devastating sentence, beautifully translated by YZ. For instance: “Du Li An thought that if she was fated to bear no sons in her life, then she’d be content with a daughter like Eggplant Face to keep her company.”

The riots’ reverberation throughout society is forever a hidden anguish for Chinese Malaysians.

LZS: I feel that female friendships have always been more susceptible, more easily swayed. Especially so in the era described in the book, when women were oppressed under patriarchy; they had to fight for resources to get ahead in a society dictated by men. Du Li An and Guen Hou’s friendship is challenged time and again by the changes in their fortunes and thus their class and hierarchy. What begins as sympathy morphs into jealousy when their circumstances change, and yet their friendship can be rekindled when one party descends into the depths of despair. In my opinion, setting aside the intricacies of female interiority, this is an inevitable result of scrabbling for limited resources in order to survive.

MZL: Yeah, it seems they can only be friends when there’s a power imbalance between them, even from the very start of their friendship. You do something very similar in the book when it comes to depicting race relations in Malaysia, which was and still can be a fraught topic in our country.

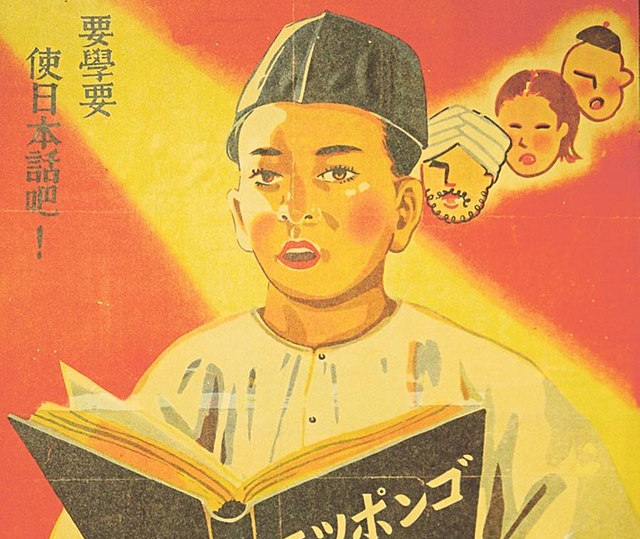

LZS: Malaysia is, after all, a multicultural society. Even though I’m writing about Malaysian Chinese stories in Chinese, it’s impossible to evade the painful and uncomfortable question of racial relations that exists perennially in the background. Though the May 13 incident is brought up and yet never directly addressed in the novel, the riots’ reverberation throughout society is forever a hidden anguish for Chinese Malaysians. I don’t think Malaysia’s issues with racial relations is something any single novelist can truly address or resolve. But since the inception of our country, every generation must find the freedom and courage to seek answers.

MZL: It’s certainly a very complex topic.

YZC: By the way, do we prefer “Malaysian Chinese” or “Chinese Malaysian?”

MZL: I’ve always said Malaysian Chinese! What do you two normally use?

YZC: Yes, same. Sorry to set us off topic!

LZS: it depends, sometimes I want to emphasize the ethnic, sometimes the nationality…

MZL: No, it’s a good point. Let me double check with Electric Literature.

LZS: Malaysian Chinese is fine for me.

MZL: There’s another storyline in the novel that has two male characters: Uncle Sai and the teenage son of the woman who lived in the Mayflower. Why did you decide to set this alongside Du Li An’s?

In Malaysia, there are so few Chinese readers, and the number of them who read literary fiction is shrinking by the day.

LZS: The origins of the Mayflower motel teen are shrouded in mystery. He has a hazy connection to the first narrative strand, that of Du Li An as the main character. What she represents is the initial generation that struggled [for rights]; as for this youth of a later generation, I dropped him into a dilapidated motel and sent him on a quest to discover his roots and find his “father,” which is akin to demanding answers from a history that always remains silent.

What I wanted to address with his section is the issue surrounding the acknowledgement of a Malaysian-Chinese identity. We’re several generations removed from the migration from China to Nanyang; our attitudes toward culture, home, and country are not the same as those of our ancestors. But this country in which we are situated—will it eternally confine us on a “Mayflower,” stranded and wrecked? Will we be chased away at a moment’s notice and exiled to our “homeland?” Though clearly this ship is going nowhere.

MZL: How does it feel to be a Malaysian writer abroad today?

LZS: To be honest, even though I have ample experience living overseas, as a Mahua writer I’ve never considered myself as being “abroad.” I’ve obviously lived outside of the country, and I’ve published in Chinese—and now English—literary circles outside of Malaysia. But throughout I’ve always thought of it as my attempts to carve out more space for Mahua literature. Malaysians who write in Chinese (versus in Malay or English) are used to being marginalized, even within the Chinese literary world. I didn’t feel like I was part of the mainstream when I lived in Beijing for several years. I felt essentially disregarded. Or, put another way, we are basically destined to have trouble blending in with our surroundings. This situation has never changed, even with the considerable sales and great acclaim that my latest novel has garnered in mainland China.

MZL: So I remember always lamenting both the fierce censorship and what I perceived to be the lack of literary or reading culture in Malaysia when I was younger. I felt like I had to leave the country if I wanted to become a writer or pursue my creative dreams. Did you two feel the same way? Feel free to tell me that I’m completely off the mark here.

LZS: In Malaysia, there are so few Chinese readers, and the number of them who read literary fiction is shrinking by the day. If you write in Malay or English, there’s no way it’s bleaker or more hopeless than writing in Chinese or Tamil, right? I keep saying: After you finish writing, the only people who will buy your book are your fellow Mahua writers or certain young readers who are basically your future colleagues—meaning only those who write will read your book, and those who write are vanishing into smaller numbers.

Luckily, we’ve always had the Taiwanese market. Quite a few Mahua authors who moved there have made a name for themselves, essentially opening up a path for other Mahua writers. But Mahua literature being Mahua literature, it’s treated, on a certain level, merely as “minority literature” in Taiwan, which, like any other place, is experiencing a decline in literary readership. The outlook for the book industry is gloomy, which means government support is essential.

All hope isn’t lost for Mahua literature even in such dire straits though. In the last few years, the work of quite a few Mahua novelists have been introduced to mainland China, where they’ve been received favorably by literature lovers. These Mahua writers have managed to draw attention despite not being physically present in China. I believe the future can only be better if we continue producing good work. Because of that I don’t completely agree with what you said about having to leave Malaysia in order to pursue dreams of becoming a writer.

YZC: I’m greatly encouraged by the success of Fixi, Silverfish, and other local publishers. I admire them so much. At the same time, I understand your concerns about censorship, especially if you work in English. I think the philosophical answer is that writing, like any worthwhile pursuit, should be done despite or against hope. And the practical answer is that we each must find what works for our art, art not being separate from “real life” of course.

MZL: OK, I have to end on this question. You’re in a Malaysian restaurant in the U.S. You have ten seconds to decide on a dish. What do you order?

LZS: I haven’t been to any Malaysian restaurant in the U.S.! Well, if I am in one of them now, oh, sure, please give me a bowl of Laksa. Maybe some satays as well?