interviews

In “The Storm We Made,” A Malayan Housewife Becomes a Spy During WWII

Vanessa Chan's novel illuminates the brutality of the Japanese occupation and the fraught intimacies between colonizers and the colonized

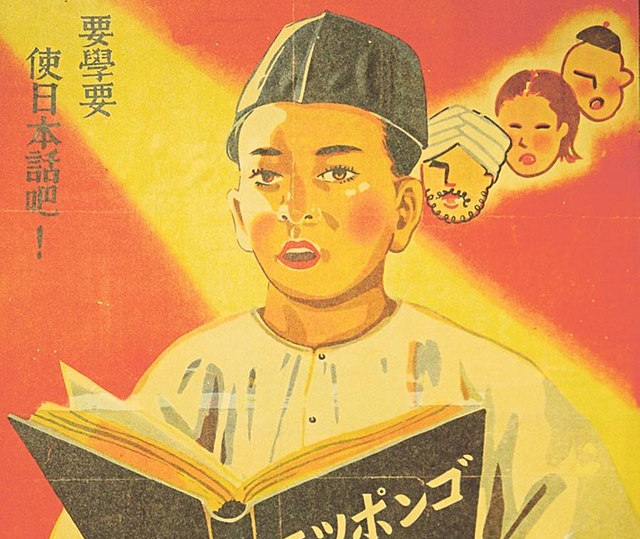

Set in World War II, Vanessa Chan’s utterly gripping debut novel The Storm We Made is the story of an unlikely spy and the consequences of her actions. When Cecily, a bored Malayan housewife in British-colonized Malaya, encounters the charismatic General Fujiwara, she is seduced not only by the force of his personality, but also his dreams of an “Asia for Asians.” Stifled by the narrow confines of her existence as the wife of a low-level bureaucrat, Cecily agrees to act as a spy for the general, unwittingly ushering in the most brutal occupation her people have ever known.

Ten years later, Cecily finds her nation and family on the precipice of destruction, and is determined to do anything she can to save them. Told from the perspectives of Cecily and her three children—eldest daughter, Jujube, who serves tea to Japanese soldiers and develops an unexpected bond with one of them; fifteen-year-old Abel, who has disappeared; and the youngest, Jasmin, who spends her days locked in the basement to avoid being sent to a comfort station—The Storm We Made moves effortlessly through time, building to a thrilling crescendo. Filled with unforgettable characters and beautiful, vivid language, this is a novel of family, secrets, survival, and resilience during the darkest of times.

Vanessa Chan is one of my closest friends and all-time favorite writers. I was lucky enough to be one of The Storm We Made’s first readers. We spoke over Zoom in the fall of 2023 about the journey of The Storm We Made, how to approach research as a historical fiction writer, illuminating a deeply underexplored time in history, the fraught intimacies that can happen between colonizers and the colonized, and the power of charisma.

Gina Chung: The Storm We Made takes place across a span of several years. You weave a very tight, propulsive plot while also grounding us in historical context. For many writers of color, I think there’s this idea that we somehow need to “explain ourselves” to a more mainstream audience when we’re writing about places that we come from. Was this something you considered?

Vanessa Chan: When I was writing it, I thought about how I would explain it to someone like me. It is true that the history of this time period in Malaysia is woefully underwritten—it’s almost not written. Southeast Asian history is really not covered by novelists or historians. I would explain things the way that the research I did through my family was told to me—where there were important explanations about dates, places, what life was like during that time. But I also balanced that with not overexplaining things that you could get in context.

I do think that history, if it’s not written, does need to be explicated, because you cannot assume that people know things that they have never had access to. And it is the responsibility, I think, of the novelist and especially of the historical fiction novelist to explain what happened during that time, if no one else has any context. But at the same time, I think things like names of food or small phrases can just be gotten in context. So I wasn’t purposely obfuscating in order to make a statement about the colonization of literature, but at the same time, I was also not trying to explain too much. I just talked about it the way that I would hear a story like this.

GC: You give us a wide cast of characters in this novel, while also anchoring the story in the perspectives of Cecily, a mother, and her three children. Can you talk about how you created these characters?

VC: When this book was first being written, it was initially a book about three sad children living through the war. And we need to have space to tell stories that are inherently sad, but for me personally at the time, I was going through a series of personal griefs, and it was also the pandemic. We couldn’t go anywhere, and I, a person who felt like I had no agency at the time, was writing about three children who had no agency at the time. I needed to bring myself some joy and infuse some of that into the book, so I wrote about their mother, who, as happens during the book process in ways that you don’t expect, became the main character. She’s this flawed woman who is a spy, and gets to run around and do things, both good and bad. I think that brought both myself and hopefully the book a bit more movement and joy.

GC: What role do whiteness, white supremacy, and colonialism play in the dynamics of the novel and in Cecily’s fateful decision to become a spy for the Japanese?

VC: This novel is set in two timelines across British colonialism and Japanese colonialism. Obviously, because the British colonized Malaysia for over 150 years, that infused everything to do with the book. But less directly, the characters in the novel are a race called Eurasian, which means a different thing in Malaysia and in Southeast Asia than it does in the U.S. Here, it means people who are mixed—European and Asian. But in Southeast Asia, it means a specific race of people who were born out of colonial intermixing—mostly Portuguese intermixing, but also some others like Dutch, the English, and the French. And because these people are born out of colonial intermixing with white people, white supremacy is inherent in that culture—the idea that the fairer you are, the closer to white you are, the better your English is, the more educated you are, the higher you are in the totem pole, the closer you are to the colonial masters and to the ideal. And all of these dynamics play a part in The Storm We Made and in Cecily’s psyche, and also her rebellion against these structures that she’s told are the way that things should be.

GC: A recurring theme in the novel is obsession, particularly Cecily’s obsession with the charismatic General Fujiwara. She’s really drawn to the general, but she also hates that she is in thrall to him. What, if anything, did you want to say or explore about obsession and its consequences with this novel?

VC: I think I want to reframe that a little bit. The reason that I wrote the character that way is because I am extremely preoccupied with the idea of charisma, and whether it is inherent or it can be taught, as well as the effect charisma has on people. Obsession is often the byproduct of someone’s charisma. This is a feature across a lot of my work and definitely in this novel. I think Cecily is taken in by the charisma of this general and his ideas. She’s smart enough to know that something is wrong, and she doesn’t understand why she’s so drawn and feels so compelled to do these things, but she does it anyway. I also sometimes wonder if the impact that charisma has on people is situational, which is the case with this book. Fujiwara and his charisma hit Cecily exactly at the right time in her life, because she was feeling particularly dissatisfied. I sometimes wonder if different charismatic people in history—both good and bad—had hit at different times in history, would their impact have been the same?

GC: The world of The Storm We Made—particularly the impact of the war and competing colonial interests on the Malayan people—is powerfully and vividly portrayed. What did your research process for this novel look like?

It is true that the history of this time period [the Japanese Occupation] in Malaysia is woefully underwritten—it’s almost not written.

VC: It’s really interesting, because I think there’s this idea—almost a rule—where writing historical fiction is like, method. A lot of historical fiction writers are known to immerse themselves in a very deep way in their characters before they write them. But I started this novel in a burst of surprise, in response to a prompt, and kept writing the majority of it during the pandemic, when the archives were closed, and there was no ability to do a ton of primary research. People sometimes ask me, “Did you interview thousands of survivors?” And sadly, there are not thousands of survivors to interview. A lot of what I wrote was based on things that had followed and infused my family’s lore and storytelling over the years. I just put those on paper and realized that it was a more significant amount than I thought it was, enough to build a book, and then I went to check all of this later. I did talk to my grandmother—she was the fount of most of these stories that I had heard over the years. My father also helped me fact-check the novel, because he’s a big history buff. My uncle sent me an old book of photographs from Malaysia over the years, when he heard I was writing this book. In a way, it sort of became a family affair.

GC: Speaking of family, what role does family, whether it’s your own or just themes of familial love and connection, play in your writing?

VC: Family is very important to me, and because this is a book about a family based on some of my family, I don’t think I could have done it without the relationships that I have with my family. Someone asked me once, “Why did you write in four POVs?” I think I wrote in multiple POVs over multiple timelines because I come from a very noisy, dramatic family that’s used to talking all at the same time—that is how I’m used to receiving information. So my family didn’t just inspire the plot, they also inspired the form. My mother also passed early on, when I was writing the novel. I had just started to write it, and I used to shamefully post, on Instagram Stories, bits that I’d written of this novel and of other stories. I would delete them quickly after, but she learned how to screenshot and expand them so she could read them, and towards the end, when she was quite ill, she couldn’t really talk that much, and we didn’t have much to talk about, because it was the pandemic, she’d make me read these bits to her, because her eyes were going.

GC: You wrote this novel during an extremely dark period in our own history, and you’ve also spoken about the devastating losses that you experienced during this time. How did the times in which you were writing impact these times that you were writing about?

VC: I think when I first sent this book out, agents could tell that the novel was perhaps written at two different times, because the first part moved a bit more slowly, and was angrier and sadder. And then the next part moved quickly, and people moved through time with speed. I think that is almost a direct impact of the circumstances we found ourselves in. The first parts of this novel I wrote in 2020, during lockdown. And then the world grew a little bit, when we were allowed to step outside—that’s when I wrote the part of the novel with more agency.

I was preoccupied with the idea of what we do when we are faced with circumstances beyond our control and still have the minutiae of our lives to live.

I was also, at the time, preoccupied with the idea of what we do when we are faced with circumstances beyond our control and still have the minutiae of our lives to live. When I talked to my grandmother, I’d ask her, “What did you do during the war?” She’d be like, “We went dancing at the neighbors’ house. Do you think we just sat at home and cried every day?” There were some days where they cried, and other days where they would squeeze through the hole in the fence to go to the neighbors’ house and have little dance parties after curfew. I always think that if our descendants ask us down the line, “What was it like during the pandemic? What did you do?” We’d be like, “We were quite sad, but everything went on. We went to school on Zoom. We had our little petty grievances, and our lives continued. It was just overhung with a shadow of a larger world event.” I wanted to write a similar idea—that there’s a big war going on, but also you have petty nonsense going on in your life. You have family arguments, little loves, crushes, and things like that.

GC: Your book is going to be published in more than twenty languages and regions worldwide! How does it feel to know that your book is going to be read by so many readers around the world? Can you tell us what the process of going out on submission was like?

VC: It’s really thrilling to know that Malaysia, which is a small country, is going to have a place on bookshelves all over the world, in all these different languages. The process of selling this book was fairly chaotic. My agents sent this book out, and I had already had a trip planned to go back to Malaysia for the Lunar New Year. The manuscript went on submission, I hopped on a plane a day and a half later, and then I got back online, and I had all these messages, and they were like, “There’s been a lot of interest in your book, and you have to do phone calls with these editors.” I was on calls with NYC editors from 10 pm to 12 am and 4 am to 6 am local time. I did a number of these on my dad’s not-great Wifi in the middle of the night, while my dad tried to cook dinner and eavesdrop behind me. So it was wonderful and chaotic. The book also sold in a number of other countries at that time. The most touching, for me, was learning that the book would also have a publisher in Japan. I received a long letter from a publisher in Japan who wanted to publish the book that basically said, “It’s time for us to show Japanese people’s stories that aren’t just about Japanese soldiers going to the front and the women that they left behind, but also about the people that they impacted during this time.” I’m not a very teary person, and I was quite emotional when I got that request.