Novel Gazing

The Book That Made Me a Feminist Was Written by an Abuser

"The Mists of Avalon" changed my life—how do I reconcile that with what I now know about its author?

Novel Gazing is Electric Literature’s personal essay series about the way reading shapes our lives. This time, we asked: What book was your feminist awakening?

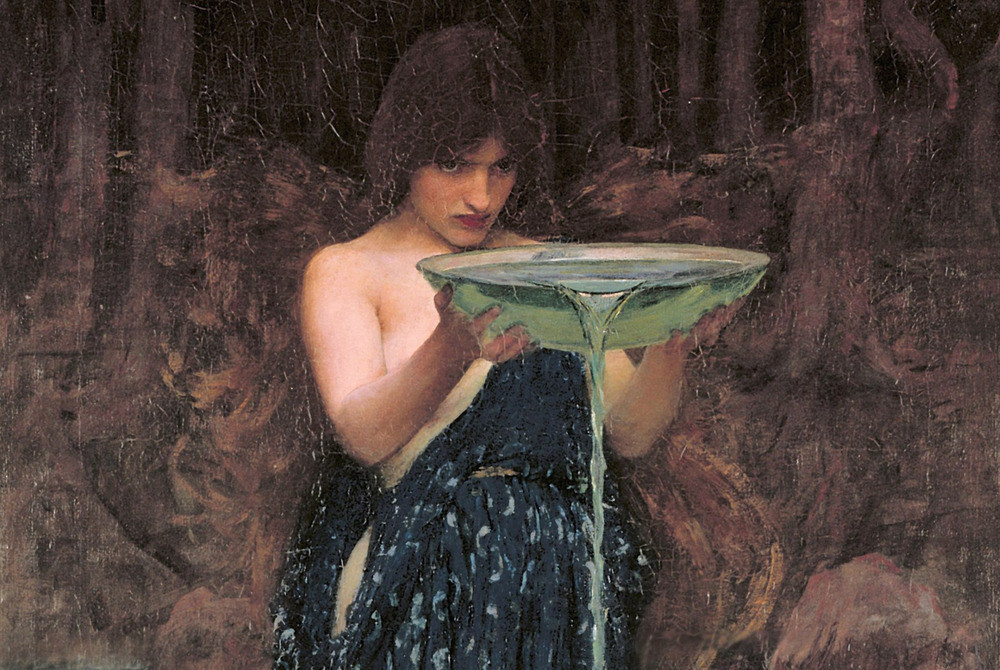

The painting on the cover stopped me in my tracks, right there in the science fiction/fantasy section of Waldenbooks at Chapel Hill Mall in Akron, Ohio. The central figure is a woman. She’s not naked, nor is she wearing an armored bikini or an approximation of medieval dress that allows for ample cleavage. Instead, she is wearing a voluminous robe, her long, dark hair bound by a simple coronet. She is sitting on a beautiful white horse and grasping a sword by its blade. She looks determined, but serene, fully self-sufficient.

There’s not a man in sight.

And that evocative title! The Mists of Avalon. I’d already read — and loved — T. H. White’s The Once and Future King, which had led me to Howard Pyle’s take on Arthurian legend, as well as John Steinbeck’s. I’d even muddled through La Morte d’Arthur. Bradley’s reference to the island where Arthur rests made me feel like an insider, while the marketing copy suggested something radically different than anything I’d encountered before: Arthurian legend, from the female perspective.

I still cannot imagine anything more perfectly aligned with my thirteen-year-old sensibilities than Marion Zimmer Bradley’s masterpiece. Bradley opened my eyes to the idea that, when we look at the past, we are only ever seeing a small part of it — and usually, what we are seeing excludes the experiences of women. Encountering the vain, self-serving, diabolical Morgan le Fay transformed into the priestess Morgaine compelled me to question other received narratives in which women are to blame for the failures of men. The Mists of Avalon also gave me a glimpse of spiritual possibilities beyond male-dominated, male-defined religions. In retrospect, I can see that it gave me ways of seeing that helped me find the feminine even within patriarchal systems while studying religion as an undergrad. The impact of this book lingers in my feminism, certainly, but it also influenced my scholarly interest in folklore, and it still informs my personal spirituality.

But my primary reaction to The Mists of Avalon, when I first read it, wasn’t intellectual; it was emotional. Like The Once and Future King, Bradley’s novel follows its protagonist from childhood into old age. I sympathized with the girl Morgaine, and her adolescent experiences hinted at frustrations I was just beginning to feel. The moment when Morgaine and Lancelet are, finally, about to become lovers — and then Gwenhwyfar, blonde and fair and lithe and helpless, stumbles into Avalon… No matter how many times I revisit this scene, it still crushes me. This isn’t a story about the pretty girl, the princess. It’s the story of the smart girl who becomes a powerful woman. Even so, Bradley brings nuance to these characters. She shows us Morgaine doing foolish, selfish things, and she shows us that Gwenhwyfar’s position is an impossible one. Doom hangs over Arthur’s glorious reign, just as fate rules many a legend and fable. There is no happy ending for anyone at Camelot — there never has been — but Bradley shows us real people struggling against their destiny, and she shows us that it’s not just impersonal fortune to blame for their inevitable downfall. Instead, it’s systems of oppression. By the time I left home for a women’s college in 1989, I’d reread The Mists of Avalon several times. I arrived ready to smash the patriarchy.

By the time I left home for a women’s college, I’d reread The Mists of Avalon several times. I arrived ready to smash the patriarchy.

And then, in 2014, Moira Greyland, Marion Zimmer Bradley’s daughter, told the world that her mother had sexually abused her and many other children for more than a decade. I didn’t even know how to process this information. I believed Greyland, absolutely, but I just couldn’t make this revelation fit with The Mists of Avalon and what that book meant to me. Bradley was not an author to whom I had a personal attachment. I’d never gotten into anything she’d written besides The Mists of Avalon. Had I been more of a fan, I might have seen the pedophilia threaded through her other work. I might have known that Walter Breen — Bradley’s husband and Greyland’s father — died in prison after being convicted of molesting a child. (Greyland says that there were many, many more victims.) Had I been more of a fan, I might have known that rumors about Bradley and Breen had circulated in the science fiction and fantasy communities for years.

My connection wasn’t with Bradley, though. My connection was with Morgaine and Viviane and Morgause — the characters Bradley created. When I read Greyland’s story, I immediately thought of one scene in The Mists of Avalon that suddenly seemed suspect, but that was it. Wondering what I might have missed, I decided to read the novel one more time.

The scene that I remembered was right where it had always been:

She stretched out her arms, and at her command she knew that outside the cave, in the light of the fecundating fires, man and woman, drawn one to the other by the pulsating surges of life, came together. The little blue-painted girl who had borne the fertilizing blood was drawn down into the arms of a sinewy old hunter, and Morgaine saw her briefly struggle and cry out, go down under his body, her legs opening to the irresistible force of nature in them.

The sexual act described here takes place around the Beltane fire. As a young reader, I was disturbed by it, but I saw it as a description of people who have passed beyond the normal world and into the sacred time of a fertility ritual. The scene was frightening for me as a child, and repellent, but also, I must admit, fascinating. In context, this passage made sense: The horror of the scene was an element of its power.

And that was all I found. Everything I had always loved about the book was still there, and I didn’t find anything new to hate. So, what was I going to do with this book?

This is, of course, a version of the question we’re all asking ourselves at the moment. How do we separate the artist from the art? Should we? Can we? I have found that my own answers vary. Woody Allen’s face makes Annie Hall, Crimes and Misdemeanors, and Hannah and Her Sisters — all movies I’ve adored — impossible. I’m also done with Louis C.K., but I’m not even ready to think about the colleagues and collaborators — Pamela Adlon? Aziz Ansari? — who have supported him, even as I, myself, was long willing to let “rumors” be “rumors.” Losing Kevin Spacey isn’t hard for me, but forswearing Harvey Weinstein forever means forgetting about a long list of great movies. And Weinstein was a producer — a facilitator more than a creator. Is his connection to a film close enough to make that film anathema?

Jodi Kantor, Megan Twohey, and Ronan Farrow’s reporting on Weinstein seems to be a tipping point for sexual harassment and assault in Hollywood, but we’re also seeing women and men come forward in journalism, publishing, and academia. The question of separating the abuser from his work metastasizes, and I don’t have any easy answers. Or, rather, I do have one easy answer: When someone says they’ve been assaulted, abused, harassed, I believe them. But I believe them, in part, because of lessons I absorbed from The Mists of Avalon.

When someone says they’ve been assaulted, abused, harassed, I believe them. But I believe them, in part, because of lessons I absorbed from The Mists of Avalon.

So, what to do with this once-beloved book? I’ve read it once since Greyland spoke out, and I don’t know if I will read it again. Probably not, I’m guessing. Discovering that powerful men are predators is disturbing, but not surprising. Learning that the author who introduced me to feminine spirituality and the hidden side of history abused children — girls and boys, her own daughter — was horrifying in an existential kind of way. I’m a writer and an editor and I know that characters can exceed their creators. I would go so far as to say that that’s the goal. So I can keep Morgaine — what she has meant to me, what she has become in my personal mythology — while I reject Bradley.

I no longer recommend The Mists of Avalon to other readers, and I can’t imagine burdening a child with it. There are other stories. Monica Furlong’s books Wise Child and Juniper are now my go-to titles for youngsters. Manda Scott’s Boudica series are the books that I wish I had found when I was thirteen, and I’m eagerly awaiting the sequel to Nicola Griffith’s Hild. It’s entirely possible that these stories about powerful women might never have been published if not for the success of The Mists of Avalon. This is part of Bradley’s legacy, too. But, even if I can appreciate the extent to which this author created a space for a new kind of writing in fantasy, I am still haunted by the voices she silenced.

When she finally came forward with her story, Greyland said,

[O]ne reason I never said anything is that I regarded her life as being more important than mine: her fame more important, and assuredly the comfort of her fans as more important. Those who knew me, knew the truth about her, but beyond that, it did not matter what she had done to me, as long as her work and her reputation continued.

I believe Moira Greyland. Her life matters more than any fiction.