Books & Culture

The Girls Finds the Horror in Murder — and Being Fourteen

Electric Lit is just $4,000 away from our year-end fundraising goal of $35,000! We need to hit this target to get us through the rest of 2025, and balance the budget for 2026. Please give today! DONATE NOW.

“Don’t read the comments” is the cardinal rule of the Internet, but if you make an exception for anything concerning Emma Cline, you’ll start to see a pattern. “Really, ANOTHER Manson book? Noooooo! Say it ain’t so!” one reader among many bemoans in the comments of Cline’s 2014 Paris Review essay about her correspondence with Rodney Bingenheimer, published long before her debut novel ever hit shelves.

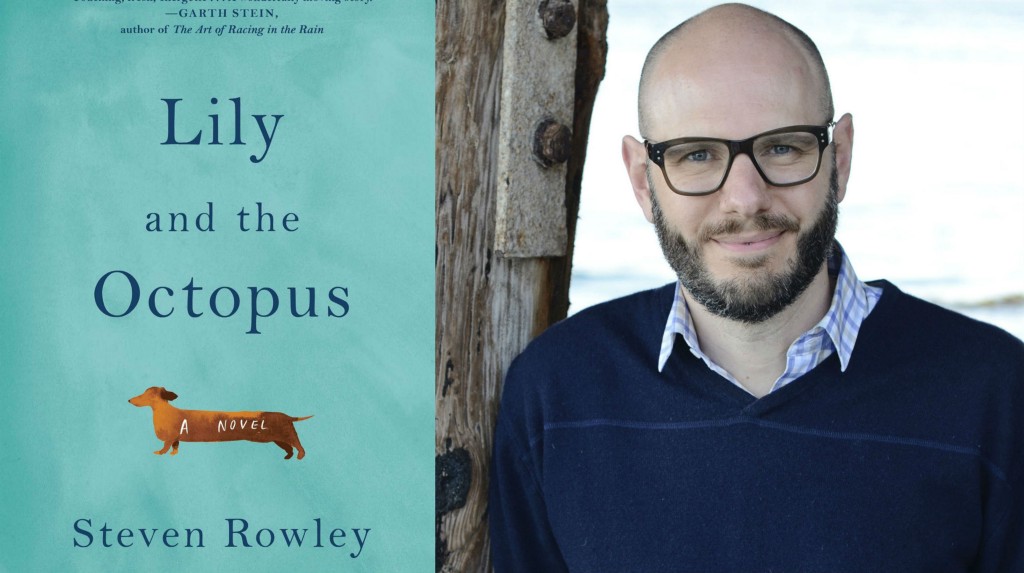

But keen eyes would have caught in the section just before comments her short biographical note, which explains that Cline is working on a book inspired by the Manson murders — a book that eventually became 2016’s The Girls. And while it is true that The Girls is technically “another” Manson book, it is also liberally fictionalized — “Russell” replacing Charles, “Mitch” a stand-in for Dennis Wilson.

You might go as far as to consider that the protagonist Evie is, in some parallel universe, Cline herself, as the author confesses in her Paris Review piece that, “In the photographs I saw of the [Manson] girls… I recognized something of myself at thirteen, the same blip of longing in their eyes.”

But might all women find their teenage selves in that blip? It’s a question The Girls raises, as longing and desire are the twin forces ricocheting in Cline’s beast of a debut. Only clumsily might it be categorized as “Manson fiction,” though; more centrally, it is one of the darkest and most alluring coming-of-age novels to drop in a good while. A sharp-nosed publisher picked up on this too, as Cline stunned the literary world when The Girls sold for a $2 million advance almost two years ago.

Still, we must be patient with the grumpy internet commenter; in a cattish sort of way, one wants very, very badly to find something to tear down in The Girls. Her hefty advance aside, Cline is still somehow only 26 — a fact that has prompted corners of the internet to mutter, “She didn’t live through the 60s. So what does she really know? This all sounds like hype.” (This garnered a sharp reply: “Really? You really just sound envious.” “WHO WOULDN’T BE ENVIOUS; THIS IS COMPLETELY INSANE,” another commenter rightfully points out.)

So yes, there is a lot that makes one want to secretly see Cline fail — her age, her subject, her hype, her advance. Unfortunately for comment sections everywhere, The Girls will not give those seeking to eviscerate it much ammunition.

At the center of the story is Evie Boyd, who is doomed to be shipped off to boarding school at the end of the summer, has newly been scorned by her best friend, and is just beginning to understand the complicated power dynamics of sex. Being fourteen, Evie is at the height of that tender and treacherous age where one wants so badly to be wanted, and it doesn’t matter by whom.

We were like conspiracy theorists […] seeing portent and intention in every detail, wishing desperately that we mattered enough to be the object of planning and speculation. But they were just boys. Silly and young and straightforward; they weren’t hiding anything.

It is an observation made only after much reflection, as a present-day Evie recalls the final years of the 1960s and her brush with history. But later her words gain a double meaning as her fourteen-year-old self draws closer and closer to a new sort of family — a group of girls that live on a dirty farm in the hills of Northern California. On the ranch, “the girls” all but worship a mysterious, charismatic man named Russell, whose every word, gesture, and affection is cherished and hungered for. “Portent and intention in every detail,” indeed.

But even on the farm, far from the reaches of society, the girls cannot escape the suffocating yoke placed on women — the pressure to please. Even while Evie begins to navigate her budding independence, she is like putty in the hands of an older girl named Suzanne, whose affections are as brief and fleeting — and coveted — as Russell’s.

At times, The Girls can threaten to be oppressing in its single-minded vision of the world and of girlhood — Cline imbues a kind of helplessness in her characters that are caught in the web of an inescapable system. So too is it true that pop culture is saturated with stories about “dangerous” teen girls: Carrie, Jennifer’s Body, Heathers.

But what makes The Girls different is how muted the violence is: here, the monster is not women but expectation. The girls ultimately succumb to being who they are wanted to be.

For Cline, though, women are not to be blamed for weakness or for seeking to please. The red hands instead belong to society itself — a churning, unnamed force that pushes everyone toward their end even as the novel draws inevitably closer to the only finale it could have: murder.

The true evil in The Girls is greater than any one individual, and so much more powerful than a single time or place. It doesn’t take living through the 1960s to understand that as a girl, you have a role you are expected to play and it is so very hard to deny that part when it is, at long last, your turn to step into the light:

That was part of being a girl — you were resigned to whatever feedback you’d get. If you got mad, you were crazy, and if you didn’t react, you were a bitch. The only thing you could do was smile from the corner they’d backed you into. Implicate yourself in the joke even if the joke was always on you.

The Girls revels in how deliriously intoxicating — and dangerous — it is to find oneself desired, and Cline is an enviable talent right out of the starting gate. Even the crankiest among us will be forced to admit that being jealous has never been quite this much of a pleasure.