Lit Mags

I Believe the Man in the Attic Has a Gun

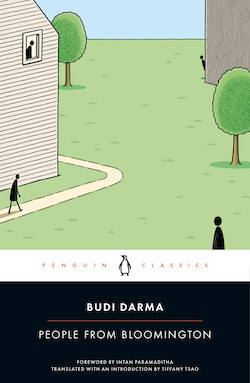

"The Old Man with No Name," from PEOPLE FROM BLOOMINGTON by Budi Darma, translated and recommended by Tiffany Tsao

Introduction by Tiffany Tsao

“The Old Man with No Name” is the opening tale of Budi Darma’s short story collection People from Bloomington. He penned the set of seven stories in the 1970s, during the years he spent as a master’s and doctoral student in the English department at Indiana University, Bloomington. Except for a fleeting mention that one narrator is a “foreign student,” the stories are about Bloomingtonians and feature an all-American cast. In a global literary climate that tends to value Indonesian literary works as ethnographic material on Indonesian culture, Budi Darma’s People from Bloomington quietly refuses to play by their rules.

“The Old Man with No Name” sets the stage perfectly for the collection as a whole, describing Bloomington through the eyes of a newcomer and introducing thematic concerns that will be significant throughout all the stories: severe loneliness, the atomization of modern society, mysterious illness, and old age, to name a few. During our correspondence on the translation of his work, Budi Darma described his encounters with old people who would “chase” him to tell him stories, or frequent supermarkets to avoid being lonely at home.

“The Old Man with No Name” sets the stage perfectly for the collection as a whole, describing Bloomington through the eyes of a newcomer and introducing thematic concerns that will be significant throughout all the stories: severe loneliness, the atomization of modern society, mysterious illness, and old age, to name a few. During our correspondence on the translation of his work, Budi Darma described his encounters with old people who would “chase” him to tell him stories, or frequent supermarkets to avoid being lonely at home.

His compassion for these elderly Bloomingtonians is especially apparent in his portrayal of the nameless, friendless man in “The Old Man with No Name.” And the fact of this compassion highlights another theme of the collection, already implicit in the story’s non-Indonesian subject matter: the universality of the human condition. Budi Darma felt moved to write about old people in Bloomington, and people generally, because he felt that he was able to empathize with and understand them. Indeed, in his preface he writes, “These stories just happen to be set in Bloomington. If I had been living in Surabaya or Paris or Dublin at the time, I would likely have ended up writing People from Surabaya, People from Paris, or People from Dublin.”

I am often wary when writers make claims about the ability and right of fiction to roam untrammeled across race, culture, and countries. Overwhelmingly, such roaming tends to be unidirectional, with Western writers depicting other people and countries rather than the reverse. Works like Budi Darma’s People from Bloomington are exceptions to the rule. If arguments defending a writer’s right and ability to cross cultures are to maintain currency, then the Western literary community must show themselves able to appreciate literary works that run counter to what they are accustomed to. Thankfully, appreciation is all too easy when it comes to Budi Darma’s darkly humorous yet profoundly sympathetic tales.

– Tiffany Tsao

Translator of People from Bloomington

I Believe the Man in the Attic Has a Gun

Budi Darma

Share article

“The Old Man With No Name” by Budi Darma

Fess Avenue wasn’t a long street. There were only three houses on it, all with attics and fairly large yards. Drawn there by an ad in the classifieds, I moved into the attic room of the middle house, which belonged to a Mrs. MacMillan. She herself occupied the lower floors. Such being the case, I had an excellent view—not only of Mrs. Nolan’s house, but Mrs. Casper’s as well.

Like Mrs. MacMillan, these two neighbors had been without husbands for a long time. Since Mrs. MacMillan never spoke about her own situation, I never found out what happened to Mr. MacMillan. But she told me that Mrs. Nolan lived alone due to her ornery disposition. As a young newlywed, she would often beat her husband. And one day, she’d arbitrarily ordered him to scram, threatening him with further beatings if he made any attempt to return. Since kicking him out, Mrs. Nolan had shown no desire to live with anyone else at all.

Mrs. Casper’s was a different story. She hadn’t cared much about her husband, a traveling salesman who’d rarely been at home. Whether he was in the house or elsewhere, it appeared to make no difference to her. It was the same when he died in a car accident in Cincinnati. She had betrayed no sign of either sorrow or joy.

That was the extent of my knowledge, for that was all that Mrs. MacMillan told me. Don’t try to manage the affairs of others and don’t take an interest in other people’s business. This was what Mrs. MacMillan advised by way of conclusion once she was done telling me about her neighbors. It was the only way, she said, that anyone could ever hope to live in peace.

Furthermore, she continued, for the purpose of maintaining good relations between her and myself, I was only allowed to speak to her when necessary, and only ever on the phone. Therefore, I should get a telephone right away, she told me. And until the phone company came to install my line, I was forbidden from using hers. After all, she said, there was a public phone booth a mere three blocks away. She went on to say that the key she’d lent me could only be used for the side door. Her key was for the front entrance. This way, we could each come and go without bothering the other. Also, she continued, I should leave my monthly rent check in her mailbox—for I had a separate mailbox from hers, located on the side of the house. I must say, initially, I found these terms extremely agreeable, for it wasn’t as if I liked to be bothered by other people myself.

The whole summer passed without any problems. I used my time to attend lectures, visit the library, take walks, and cook. And every now and then I would sit contemplatively in Dunn Meadow, a grassy area where there were always lots of people. I bumped into Mrs. Nolan and Mrs. Casper a few times, but as neither of them showed any desire to become acquainted when I tried to approach, I too became reluctant about speaking to them.

But as summer started to give way to fall, the situation changed. As autumn approached, the town of Bloomington was flooded by thirty-five thousand incoming students—new ones, as well as those who had spent the summer months out of town. But as far as I knew, not a single one of them lived on or in the vicinity of Fess. Bloomington bustled with activity, but Fess Avenue remained deserted. Besides this, as time went on, the days grew shorter, with the sun rising ever later and setting ever sooner. And then the leaves turned yellow and, by and by, began to shed. Not only that—it rained more often, sometimes to the accompaniment of lightning and thunder. Opportunities to go outdoors became few and far between. Only now, under such conditions, did I pay more attention to life on Fess. All three of them—Mrs. MacMillan, Mrs. Nolan, and Mrs. Casper—spent a lot of time in their yards raking leaves. The leaves would then be put into enormous plastic bags, placed in their cars, and driven to the garbage dump about seven blocks away.

Mrs. Nolan had a peculiar habit. If she caught a glimpse of any animal while she was in her yard, she would immediately begin pelting it with rocks that she appeared to keep at hand for this purpose. She always managed to hit her target, even without taking aim. A number of bats dangling from low branches were dispatched; the same went for assorted birds that had just happened to stop by, only to perch within stoning distance of Mrs. Nolan. It wasn’t just her throwing abilities that were impressive, but also the extraordinary vigor that enabled her to wound and terminate the lives of so many animals. Her actions weren’t illegal, of course, but I wondered at how she never attempted to be more surreptitious. How she disposed of the poor creatures’ bodies remained a complete mystery to me. I was positive that both Mrs. MacMillan and Mrs. Casper knew about Mrs. Nolan’s behavior. Yet it came as no surprise to me that they simply let her be, without attempting to raise the matter or report her to the police. Apparently, it was by carrying on without interfering with each other that they were able to get along well.

Mrs. Casper didn’t possess exceptional qualities like Mrs. Nolan, but it was hard to ignore her all the same. She was old and sometimes looked unwell, and when she looked unwell, she was unsteady on her feet. When she was in good health, she was capable of a brisk stride. I often thought to myself that if she ever had cause to run, she would manage a good sprint.

All three women shopped at the local Marsh Supermarket from time to time. It was a small branch, which sold both regular goods and ready-made foods, not far from the nearby phone booth. Naturally, since it was such a quiet area, the store didn’t have many regular customers. The owner himself didn’t seem to expect much business. The main thing was that the store could keep trundling along, and he seemed satisfied on this front. In keeping with the general atmosphere of the neighborhood, he wasn’t friendly, speaking only when required. Personally, I only shopped there if I couldn’t get to College Mall with its many affordable stores, some distance away.

To combat my loneliness, I’d sometimes flip through the phone book. In its pages, I discovered the numbers for Mrs. Nolan, Mrs. Casper, and the nearby Marsh. Over time, once we were well into autumn and the days had grown even shorter, and strong winds had become a regular occurrence, as had lightning and thunder storms, I set about killing the lonely hours by playing telephone. At first, I’d dial the recorded voice that would give me the time, temperature, and weather forecast. That sufficed initially, but over time, grew less effective. I began calling various classmates. They responded in the same way they did when I met them on campus, in as few words as possible, until I exhausted all possible topics of conversation. I began ringing up Marsh, asking if they stocked bananas, or apples, or spaghetti—anything really—which ended up annoying the owner. Mrs. MacMillan didn’t seem too happy either whenever I called her with some made-up excuse. Like the store owner, she seemed to know full well that I had no real reason to talk.

At last, one rainy night, I phoned Mrs. Nolan to ask if I could help clean up her yard. This seemed not only to surprise her, but enrage her as well. Was her yard that filthy, that disgusting, she inquired. When I answered, “No,” she asked what my ulterior motive was. I just thought she might need some help, I said, upon which she asked whether she looked so sickly, so feeble, that I felt compelled to offer my services. Naturally, I replied that she looked perfectly healthy. She promptly told me, “If I need anyone’s help, I’ll place an ad.”

After this conversation, I didn’t dare to phone Mrs. Casper.

One night, as the rain fell outside in a steady drizzle, something changed. There was a light on in Mrs. Casper’s attic. And it remained on every night. I soon found out that someone was living there—an old man who looked about sixty-five years old. Every morning he would poke his head out the window and take aim at the ground below with a pistol, like a child playing with a toy. But I was certain that what he was holding was a real gun. And if I was right, something terrible might happen. So I immediately called Mrs. MacMillan. She thanked me for informing her, but then tried to bring the matter to a close: “If Mrs. Casper really does have a boarder in her attic, then that’s her business. Just like you living here is mine. If he really does have a gun, he obviously has a permit for it. And if he doesn’t have a permit, then they’ll arrest him at some point.”

Every morning he would poke his head out the window and take aim at the ground below with a pistol, like a child playing with a toy.

I made a hasty attempt at protest before she could hang up. “If anything happens, won’t it be bad for us?”

“As long as we don’t bother him, what could happen?” she replied.

And that was the end of the conversation.

The next morning, under the pretext of buying milk, I took a walk to Marsh. Naturally, I took the opportunity to check whether there was a new name on Mrs. Casper’s mailbox, but there was no name to be found. While paying for my milk, I commented to the owner, “Looks like Mrs. Casper has a new boarder.”

“Yeah. He’s already been in a few times to buy doughnuts.”

“What’s his name?” I asked.

“How should I know?” he replied with a shrug.

Coincidentally, on the way back from Marsh I ran into Mrs. Nolan.

“Mrs. Nolan, did you know Mrs. Casper has a new boarder?” I asked.

“Yes, I do,” said Mrs. Nolan, showing no desire of wanting to talk further.

My hope that I would run into Mrs. Casper, unfortunately, remained unfulfilled.

That night, after some deliberation, I phoned Mrs. Casper.

“Mrs. Casper, I see there’s someone living in your attic.”

“Yes, I rented it out, son. Why do you ask?”

“If he needs a friend, I’d like to get to know him,” I said.

“All right, I’ll tell him. What’s your number? If he’s interested, I’ll let him know he should give you a call.”

After giving her my number, I asked for his in return. Mrs. Casper replied that he didn’t have a phone. Nor did she know whether he had any plans to have one installed.

When I asked for his name, she said she had no clue. “If he used checks to pay the rent, I’d know it, of course. But he pays me in cash. The only thing he’s told me about himself is that he fought in World War II.”

On this note, the conversation came to an end.

Things went on as usual after that, except for the weather, which got increasingly worse, and the temperature, which continued to plummet. Every day, the man would point his gun at the ground below, taking aim at a large rock beneath a tulip tree, never firing any bullets. And every night, the light in Mrs. Casper’s attic would shine steadily on. In the meantime, the old man never called me. And I never ran into him. As far as I knew, he never left the house, so I never had the chance to chase after him and pretend to bump into him by coincidence.

One morning, when the weather was particularly bad, I called the phone company to ask if anyone on Fess Avenue had recently installed a line.

“What’s the person’s name?” asked the operator.

“I don’t know. But he lives on Fess.”

“Now that’s a tough one,” answered the operator, “unless you know his name. Keep in mind, sir, since all the new students began arriving for the fall semester, thousands of people have been installing new lines.”

Her answer terminated my desire to pursue the matter further.

The next day I went to Marsh to buy a doughnut.

“Did the old man stop by recently?” I asked. “The one who lives in Mrs. Casper’s attic?”

“Why, yes. Didn’t you see him, son? He just left the store.”

“Oh, really?” I said, somewhat bewildered.

I asked whether he’d ever received a phone call from the man. The store owner shook his head.

I hurried out of the store, but my efforts to run into the old man bore no fruit. Several times I circled the area—South Tenth and Grant, Dunn, Horsetaple, and Sussex—but I saw no trace of him. Then, upon returning home, I found that the old man was already back in his room, aiming his pistol below, as usual, making shooting motions, but never firing a single bullet. I hoped that at some point he’d look my way, but my wish was never granted.

That same night I decided to write him a letter. Since no one knew his name, I could address it to anyone and Mrs. Casper would be sure to pass it along. On the back of the envelope, I wrote, John Dunlap, c/o Mrs. Casper, 205 Fess Avenue.

The letter read as follows:

John,

How about meeting at the Marsh at half past eleven on Wednesday morning? I know you like doughnuts. This time around, the doughnuts are on me, and the coffee, too.

Best wishes,

I printed my name and address.

Also that very night, I dropped the letter in the mailbox near Marsh. I’d nearly reached the mailbox when an old man came out of the supermarket. I mailed the letter and hurried after him, but he’d already vanished, having turned into a small alley connecting South Tenth with South Eleventh. I couldn’t say who this old man was for sure, but there was a chance that he might be Mrs. Casper’s boarder. I hesitated for a moment. Should I chase after him or return to Marsh first, under the guise of buying bread or cake, to find out if he really was the man from Mrs. Casper’s attic? My hesitation was to blame, I suppose, for by the time I decided to follow him into the alley, I’d lost his trail. It was only when I returned to Marsh did I receive confirmation that he was indeed the man I was looking for.

“This time he bought a tuna sandwich,” the store owner said.

Strangely, there was no light on in Mrs. Casper’s attic that night. I kept waiting, but still the light remained off. My fingers began to itch.

In the end, I gave in and phoned Mrs. Casper.

“Mrs. Casper,” I said after apologizing for calling so late, “you did tell the man in your attic about me, didn’t you?”

“Of course I did, son,” she replied promptly. “But he doesn’t seem to be interested in talking to anyone.”

“So . . . just wondering, Mrs. Casper, why isn’t the light in his room on?”

“My, my! How is that any of my business, son? He pays me rent, after all. I’m not going to stop him from doing whatever he wants, as long as he doesn’t damage anything or cause trouble.”

Unsatisfied, I pressed on. “Excuse me for asking, Mrs. Casper, but if I’m not mistaken, doesn’t he have a gun?”

“My, my! This is too much, son. What is it to you if he does have one, and what’s it to you if he doesn’t? Now, goodnight. I hope you won’t ask about him again if it’s not urgent.”

And that was the end of the discussion.

In the days that followed, everything went on as normal. On Wednesday, starting in the morning, I attempted to keep my eyes glued on Mrs. Casper’s house. As usual, at around ten-thirty, the man opened the window and began playing around with his gun. Then he shut the window. Meanwhile, I was prepared to leave the house the minute I saw him heading out through Mrs. Casper’s yard. But he never appeared. Soon it was almost twelve-thirty, and he still hadn’t emerged. Only then did I give up. Leaving the house, I walked dejectedly to Marsh.

The ground was still wet from the rain that had fallen all last night and early that morning. When I reached Marsh, I was startled to see my letter lying on the roadside in the gutter, drenched in rainwater, but saved from slipping into the sewer by a branch that had fallen from a large tree overhead. I found the letter had been opened. I had no idea whether the man had thrown it away on purpose or if he had accidentally dropped it.

“Has that old man been in today?” I asked the owner after getting some milk.

He nodded.

“About what time did he come in?”

“Oh, an hour ago or so,” he replied.

Hmm. If that were the case, then he must have left while I had been in the bathroom.

“Have you found out anything else about him?” I asked.

“Nope,” replied the owner. “Oh, wait. He did mention that he very much wanted to find some young folk to spend time with. People in their twenties, sound in body and mind—to train how to handle a weapon if the need ever arose. Then he began babbling. Said he once dropped a bomb on a Japanese ship. Darned if I know what’s wrong with that guy.”

The owner then turned his attention to sticking price tags on some canned food that had just come in. My attempts to fish for further information about the old man met with failure.

The old man in Mrs. Casper’s attic didn’t open his window that afternoon. But in the evening, I did catch a glimpse of something rather strange: Mrs. Casper leaving her house and making her way unsteadily to her car. Because it was already dark, I couldn’t see her face clearly, but I had the impression that she didn’t seem well. I ran down, but by the time I’d reached the street, Mrs. Casper had already started her car. She veered too far right as she turned the corner and almost grazed the curb.

It grew late, and there was no sign that she had come back yet. The whole house, including the attic, was dark. What I really wanted to do was phone Mrs. MacMillan, but I thought to myself, What’s the use? Then, all of a sudden, I heard a gunshot, so I called her right away. The phone rang for a long time. She must have already gone to bed or fallen asleep. Sure enough, she sounded pretty peeved.

When she asked me what kind of a shot it was, I hesitated. A pistol shot wouldn’t have been that loud, but I answered nonetheless, “A pistol.”

When Mrs. MacMillan asked where the sound came from, I hesitated once more. I’d heard the shot loud and clear, but what wasn’t clear was where it had come from. So once again, nonetheless, I replied as if I knew. “From Mrs. Casper’s attic.”

Mrs. MacMillan said that no one should meddle in Mrs. Casper’s affairs if the woman herself hadn’t asked for help. Then I told her about seeing Mrs. Casper earlier. At this additional information, Mrs. MacMillan expressed her thanks.

“She must be having an attack again. She has bouts of fatigue. Have I told you about it, son?”

When I said, “No,” she explained that Mrs. Casper had suffered for a long time from the terrible malady, and her doctor had advised her to come straight to him or go to the hospital whenever the symptoms came on.

“She should have told us so we could have helped her,” she added.

When I brought up the gunshot again, Mrs. MacMillan replied, “If you think it would do any good to report it to the police, go ahead, son. But be prepared to get a headache from all the questions they’ll ask.”

Without consulting Mrs. MacMillan, I phoned Mrs. Nolan. The phone rang for ages before she picked up. And like Mrs. MacMillan, her voice emanated extreme annoyance. After insisting that she hadn’t heard any noise, she asked if I was absolutely sure I’d heard a shot. When I answered, “Absolutely,” she insisted on knowing where the shot came from.

I answered as if there were no doubt in my mind. “Mrs. Casper’s attic,” I said.

“Then it must have been that old man with his gun. Isn’t that right?” she asked. She sounded as if she wanted me to agree with her.

Again, as if there were no doubt about it, I answered, “Yes.”

Since I didn’t know what else to say, I ended up asking, “So, do you think we should report it to the police?”

“Why by all means, son, by all means. As long as you’re fine with them thinking you’re crazy when you can’t prove it was definitely him who fired the shot.”

My desire to further discuss the gunshot waned. And when I told her about seeing Mrs. Casper, Mrs. Nolan’s response— both in tone and content—was similar to Mrs. MacMillan’s.

I couldn’t bear to stay put any longer. So I left and walked glumly toward Marsh, hoping to see something promising in Mrs. Casper’s house. At the very least, Marsh might still be open. Mrs. Casper’s house was completely dark. Even the little light on the porch was off. Yet, faintly, I could hear the sound of someone sobbing on the porch. I couldn’t do anything, of course. And I didn’t have any reason to enter Mrs. Casper’s yard, apart from curiosity. Let’s say I did go in and something happened. If curiosity was my only excuse, then it might get me into trouble.

It turned out Marsh was closed. So I turned and headed one block over. Like Fess Avenue, this stretch of road was also deserted and dark. An acute regret at renting a place on Fess rose within me once more. Nearly everyone who lived in this neighborhood was old, lived alone, and had no friends and no interest in making any. Historically, this had once been a lively area, but the town activity had long shifted away, to College Mall. On the corner of Park Avenue alone were two abandoned movie theaters that had fallen into disrepair. But I’d agreed to live in Mrs. MacMillan’s attic through December, when the fall semester came to an end. By the time I returned and passed Mrs. Casper’s house again, there were no more sounds. The house was still dark.

If curiosity was my only excuse, then it might get me into trouble.

The next day was busy, and I had to put aside all memory of the previous night’s events. In the morning I had to go to the library, and from there straight to class. And because I had so much reading to do, followed by more classes, I didn’t go home for lunch but ate at the Commons—a cafeteria in the Union building, which formed the center for the majority of campus life.

When I entered the Commons, there were practically no free seats. Over by the entrance was a long line of people waiting for food. After getting something to eat and selecting my drink, I joined another long line of people waiting to check out before taking their meals to the dining area. In the meantime, country-western music blasted over the speakers.

For some reason, I felt a bit shaky. Soon, I found I had a slight headache as well. And wouldn’t you know it, right when I glanced over at the revolving doors leading from the dining area to the lawn, I saw the old man from Mrs. Casper’s attic heading outside.

There were still about five people ahead of me, waiting to pay, and behind me there were around ten. I couldn’t possibly set down my tray of food in order to chase after him. There was no way. All I could do was wait patiently for my turn. Once I paid, another problem arose. Every seat was now taken.

This being the case, I couldn’t possibly set my food down on someone else’s table to dash out and see if the man was still there. In the end, I had no choice but to go downstairs, to the seating area for the Kiva café one level below. And as I made my way down the steps, I felt waves of dizziness wash over me.

After that last incident, there were several things that were worthy of note: Mrs. Casper’s boarder never came to the window to play with his gun anymore; the light in his room remained on all night; Mrs. Casper exhibited no signs of relapse; and I began spending more time hanging out at the Union. It was an enormous building, with many floors and many rooms, with many tables and seats where one could study, equipped with stores, a post office, and other university-owned services. And I found I never happened across the old man again.

I did go to Marsh once, and the owner told me that the old man was still an avid doughnut buyer. What time the man would show up, the owner told me, he never could tell. Something else worth mentioning: whenever I woke up, my head would start to ache, and I would initially see spots of light. I would occasionally experience the same sensations when I stood up after sitting down. And, sometimes, while walking, I would start to feel shaky.

One day, I was in the Union, walking from the bookstore toward the Commons. I was heading to the exit near the Trophy Room in order to get to Ballantine Hall, where I had to take an exam. And of all things, at that exact moment, I spied the old man heading from the Commons to the men’s room. Naturally, I seized my chance. I was at the men’s room in a flash. It was a multitude of mirrors, of sinks and electric hand dryers, of urinals and stalls. I’d just reached the urinal area when the old man swung one of the stalls shut. I didn’t need to pee, but I had no choice. Once again, I felt unsteady on my feet. I finished peeing, but even so, I pretended to keep going. Then I deliberately took my time washing my hands.

Wouldn’t you know it, while I was washing my hands, “Bang! Bang! Bang!” yelled the old man—like a kid playing with a toy gun.

I waited.

“Bang! Bang! Bang!” he kept yelling from inside the stall. A few people began to take notice, but only for a moment, before ignoring him. In order to linger on, I began using the hand dryer. Over the low roar, you could still hear the “Bang! Bang! Bang!” A few others, who’d just come in, looked curious. What happened next, I had no idea. I had to rush off to Ballantine Hall.

After the exam, I felt as if I’d been hit in the head by a sledgehammer, and my whole body felt as if it were engulfed in flames. I had to take a cab home. As we passed Dunn Meadow, I saw some kids playing. The old man was there, too, making a spectacle of himself. He was acting as if he was going to shoot them with his gun, and they were stepping backward, hands raised, as if scared of being shot.

“That vet. He’s at it again,” the taxi driver said.

When I asked what he meant, the driver replied that this wasn’t the first time he’d seen the old man in Dunn Meadow, behaving like this.

“Told me he was a bomber pilot during World War II,” the driver said. “His plane got shot down by the Japanese in the Pacific. He and two other crew members survived, thanks to their life vests. Then they were caught by the Japanese, tortured, starved, and denied medical treatment. His two friends died, and he almost did too—of beriberi. After Japan threw in the towel, he was taken to an army hospital to recover. They fed him five times a day to make up for the starvation, and he wound up marrying one of the nurses. They had two sons—one died in Vietnam and the other drowned while swimming in the Ohio River. He said his wife died, too, only recently. Of colon cancer.”

That night, I couldn’t take it longer. I was sick and needed help. I phoned the student health center, which told me to come in straightaway. Then I called a cab. I couldn’t help but grumble when the taxi took a long time to arrive.

“Sorry, man,” said the driver. “I got held up by some guy when I tried to turn onto South Tenth. I had to go back and take Park Avenue in order to get to Fess. What a moron! Cars on the road, and he’s in the middle of the street, waving a gun!”

I wanted to know more, but the sledgehammer-strength pain in my head kept me from saying anything. The taxi sped on, turning onto Woodlawn Avenue. Then, damn it all, just when we were about to turn onto South Tenth, the old man from Mrs. Casper’s attic ran into the middle of the road, pointing his gun at the driver.

“This guy again!” the driver yelled, veering away toward Memorial Stadium.

The remainder of the night was hazy to me. I think I pretty much half fainted once we reached the health center. I don’t even really know what happened the next day except that my body felt like it was on fire and I had to undergo all sorts of tests. Then, on the third day, I began to feel better. They said my condition wasn’t critical and I would be allowed to leave in a few days’ time.

In the meantime, I’d received a phone call from Mrs. MacMillan who wanted to see how I was doing. She mentioned that Mrs. Casper had returned from Monroe Hospital a few days ago. When I asked about the old man, she told me that he had frightened Mrs. Nolan with his gun, and that Mrs. Nolan had threatened to call the police. Even Mrs. Casper had expressed unhappiness about her boarder, saying he was prone to fits of rage.

That same day, the campus newspaper—which had a circulation of about fifty thousand copies—printed a letter to the editor about the old man. The letter’s writer, a Sue Harris, said that for the past few days, an old man had been roaming around the Union and Dunn Meadow, pointing a gun at anyone who walked by. Speaking for herself, Harris couldn’t tell whether the gun was real or fake. But even if he wasn’t threatening anyone’s safety, wrote Harris, he was certainly spoiling everyone’s view.

The next day the same paper ran three more letters about the old man. One, from a Susan Tuck, took the same tone as Harris. The two others, penned respectively by Cindi Cornell and Paul Smith, took issue, saying anybody and everybody had the right to have fun. If anyone didn’t like having a gun pointed at them, then they shouldn’t go near him. And if anyone felt he was spoiling their view, then they should look away. Both Cornell and Smith then testified to the service that the man was providing to those who did like to have fun. For, whenever he showed up, they said, he and his antics succeeded in amusing people who were otherwise bored.

On the third day, the same newspaper printed a photo of the man, which took up two columns’ worth of space. “The Old Man with No Name,” read the caption. After stating that they had received numerous letters and phone calls about the man, the editor wrote, “This old man, who refuses to give his name, intends to rent the twenty-third story of the Union building tower and fit it out with a machine gun and boxes of ammunition—for the purpose of self-defense if anyone tries to cause him harm.”

That was also the day I was discharged. I left the minute the nurse told me my taxi had come. My mood was overcast, influenced by the bad weather. I wasn’t particularly excited about returning to Mrs. MacMillan’s house. As the taxi pulled away from the health center, the first snowflakes began to fall, marking autumn’s end.

After dropping me off in front of Mrs. MacMillan’s, the taxi sped off. It had just rounded the corner, near Mrs. Nolan’s house, when I heard Mrs. Casper shrieking in fright: “Help! Help! Help!”

At the same time, I heard the old man yell, “Watch out or I’ll shoot you! Watch out or I’ll shoot you!”

Sure enough, there was Mrs. Casper sprinting toward me, followed by the old man, aiming his gun at her. At the sight of her terrified face and his resolute expression, I was determined to block his way in order to give Mrs. Casper a chance to escape. And when I did, it wasn’t he who fell flat, but me. Of course, the pain in my head came back with a vengeance, followed by spots of light. When I got to my feet, I heard a gun go off, followed by another shot. It was the same kind of sound I’d heard the night I watched Mrs. Casper leave her house. I could barely make out anything, but there, to my shock, were two figures lying on the sidewalk—one, the old man, and the other, Mrs. Casper. The snow was now falling thick and fast.

The old man was drenched in blood. It trickled slowly onto the pavement, the snowflakes alighting on the pool of red. I don’t know why, but I knelt beside him. His eyelids flickered open, briefly, as if he had something to tell me. But then they shut once more. And then a bellow—long and loud from his lips. And I don’t know why, but I began stroking his head. And when I tried to close his mouth, I found that his jaw had gone stiff, as hard as steel.

I became aware of an old woman standing nearby. When she spoke, I realized it was Mrs. Nolan.

“Yes, I killed him. The wretch,” she said in a defensive tone of voice. “You know full well he would have killed Mrs. Casper. That’s why I came to the poor woman’s rescue. Just so you know, son, he threatened to finish me off several times.”

When I stood up, I suddenly realized that Mrs. Nolan was carrying a short double-barreled shotgun. And I was convinced—that night, after Mrs. Casper left her house, this was the weapon that had gone off, not the pistol belonging to this poor old man. And I felt hatred for Mrs. Nolan. I remembered the squirrels and birds that had met their destruction at her hands. The woman was nothing other than, and nothing but, a murderer.

When the police and ambulances showed up, I straight out refused to be taken to the police station. Finally, they granted my request to be brought back to the health center instead. And so, under the escort of two campus police officers, I was returned to the student health center.

I couldn’t sleep that night. Even though the night-shift doctor finally let me take sleeping pills, my eyes remained wide open. I found myself pursued relentlessly by the old man’s gaze before his eyes had closed. And I couldn’t erase the memory of his mouth, gaping and unyielding as steel. I wondered, what had he been about to say? How cruel Mrs. Nolan was.

From the police, I received the information that the old man’s gun wasn’t a toy, but it hadn’t been loaded. Mrs. Casper had been lying sprawled on the sidewalk, not because she’d been shot, but because she’d fallen down in terror before fainting when she’d heard the gun go off. And, in keeping with what Mrs. Nolan herself had admitted to me, when Mrs. Nolan had looked out her attic window and seen the old man threatening to kill Mrs. Casper and chasing her with a gun, not to mention Mrs. Casper herself shrieking for help, she had gone straight for her shotgun, fully intending to strike the old man down. Mrs. Nolan also mentioned to the police that the man had threatened to shoot her many times before.

When they spoke to the police, both Mrs. Nolan and Mrs. MacMillan said that I had often seen the old man playing with his pistol, and that one night I had even heard the man fire his gun.

“So, you see, it’s not possible,” said Mrs. Nolan to the police. “The man must have kept bullets.”

For Yuwono Sudarsono

London, 1976