Interviews

Is the Patriarchy Making Teenage Girls Sick?

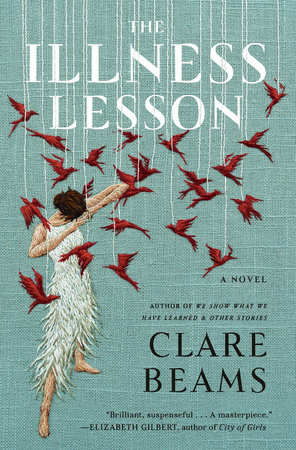

Clare Beams, author of "The Illness Lesson," on hysteria at a 19th century all-girls boarding school

Set in 1871 in a Massachusetts familiar to us thanks to Little Women, The Illness Lesson by Clare Beams takes on issues of gender equality and abuse that feel just as urgent 150 years on—possibly even more so in this particular cultural moment.

Caroline has grown up under the shadow of her father Samuel, a famous essayist and thinker known for the failure of his utopian experiment, Birch Hill. When Samuel and his protege David decide to start a school for girls, it is assumed that Caroline will join them in teaching—and in their vision of educating girls in the same subjects as boys and proving that girls can learn more than sewing and social etiquette.

When the girls show up, however, nothing goes as planned. Led by Eliza, the daughter of Samuel’s deceased nemesis, they begin secretly reading an all-but-forbidden Gothic novel and experimenting with rituals in the woods at night. Then, one by one, they begin to fall ill. Meanwhile, the area is overtaken by mysterious red birds, a species that has only been seen once before, back when Caroline’s mother and Eliza’s father were still alive.

The Illness Lesson follows on the success of Beams’s haunting 2016 story collection, We Show What We Have Learned. I spoke with Beams about hysteria, the magic of teenage girls, and writing while parenting young children.

Shayne Terry: The Illness Lesson deals with the self and what it means to be oneself. Eliza tells Caroline that she is “looking for a way to be, here” and Caroline answers that the right way to be is “of course to be yourself.” But Eliza’s fifteen! She’s figuring out who she wants to be. And that teenage impulse to try on different identities is very much at odds with the Transcendentalist ideals of the men who run the school — the belief that each girl has a “deepest self,” and all it will take is a certain amount of education to excavate it.

Clare Beams: The Transcendentalists had these noble ideas of the self, and, in theory, they applied to women as well—many of them were women, brilliant women—but there was this tension that we’re still living with, that the things we tell women about their possibilities are not the things women encounter in the world.

ST: And then there is the question of how illness affects the self. As Eliza’s body is overcome by strange symptoms, she can’t stand to feel like herself. And Caroline lives under the threat that the illness that killed her mother may be genetic, every moment wondering when a seizure might take her away from herself. The men seem to want to ignore the body—who we are is in the mind, in the soul. But, as anyone who has been seriously ill or injured knows, when the body demands attention, it has a way of taking over. What made you want to write about illness?

CB: While I had not consciously articulated all of that to myself, I knew there would be this school and that it would have this fatal flaw of not acknowledging the bodies of these girls, their femaleness. To Samuel and David, these girls are essentially genderless minds—or at least that’s what they want the girls to be. I knew there would be trouble, and it made sense to me intuitively that the trouble should come from their bodies because that’s what’s being ignored.

Anyone who’s ever been a teenage girl or been in a school knows that you’re part of something that is beyond any individual.

The men don’t deal with the whole thing well. They’re looking for ways to squelch the body and its demands. Much more than helping the girls, they are interested in silencing the problem that is being so noisy through the girls’ bodies. The illness brings out the problem with the vision for the school.

Eliza’s illness is, I think, psychogenic; she is genuinely sick, but it’s coming from her mind. That doesn’t mean that she’s not ill. This mass hysteria that overcomes all the girls—it’s their bodies, insisting on themselves.

ST: That brings me to another of the book’s preoccupations, which is the mysterious magic that can arise within a group of teenage girls. It has echoes of the beginning of the Salem witch trials, though this story takes a very different turn.

CB: Anyone who’s ever been a teenage girl or been in a school knows that you’re part of something that is not yourself, that is beyond any individual. The group is not the same thing as the sum of its parts. These girls become their own organism, and the group has its own power.

A psychogenic illness spreading through a group is a real historical phenomenon that has happened periodically—I recently wrote about it for Lit Hub. It tends to happen in schools, and it tends to happen to adolescent girls. No one is faking. The illnesses are real, but the causes are not concrete. The brain has a power over the body, and the body can respond first to tensions that arise in the mind.

ST: Yet, when the girls begin to fall ill, the men around them ignore their bodies in a whole new way, deciding that the sickness must be in their ideas. These girls are presenting with physical symptoms and the men are basically saying, “It’s all in your head.”

CB: In a certain way, Samuel and David are correct, but when they say it, they mean, “This isn’t real.” The illness is real—it’s just not something the girls have caught from, say, the water.

The girls have been taught that someone else knows more than they know about their experience, and yet their bodies keep insisting on a truth.

ST: This gaslighting and the doctor’s “treatment” feel, sadly, very current.

CB: Yes, the book has these current echoes, and there are certain parallels with things that have become part of the cultural conversation recently, such as the abuse perpetrated by Larry Nassar, although what happens to the girls was in the book before that came to light. I think there’s something so weird about that, that a book set in 1871, which was fully drafted in 2014, should have these resonances. I had a draft before #MeToo was the thing it became, although, of course, the forces that produced it have been around forever. It makes you wonder: how has so little changed?

ST: The girls’ illness is diagnosed as a case of hysteria. We get quotes from the historical literature on hysteria, including the fantastical metaphors that were used to describe it: the womb as an animal within an animal, the womb as a wanderer liable of getting lost. And then the 19th century’s “modern” way of thinking about it: “pelvic congestion,” with its long list of symptoms, painful menstruation and abdominal heaviness lumped in with ticklishness and worry. Most women I know could claim multiple symptoms from that list on any given day. To this doctor, we’d all be hysterical.

CB: Part of what fascinated me about this is that I have been amazed, as a woman, how much we still don’t know, medically, about women’s bodies — we just don’t know anything! Historically, no one has wanted to study women. There’s a weird squeamishness about it, an astonishing vagueness and lack of knowledge.

ST: Yes! When I was pregnant, there was an issue with my cervix, and when I asked the midwife why it was happening, I was met with a shrug and told, “We know very little about the cervix.”

CB: Almost every woman has something like that in their medical history. “We found this weird thing, we don’t know if it’s really weird or if you’re just a woman. Take this information and try not to be too anxious.” That, to me, is also fascinating.

ST: Let’s talk about the birds. You received a glowing review from Publishers Weekly, but I felt they totally missed the point of the trilling hearts, the eerie red birds that take over the town. They called it a “fantastical thread” that didn’t fit with the “otherwise plausible plot.” But the birds are the plot! The birds are the girls, and the girls are the birds!

CB: I know! I love most of that review. But the truth is that the birds were there before anything else. I start with an image when I write, and this time it was an image of those red birds.

The brain has a power over the body, and the body can respond first to tensions that arise in the mind.

Originally, the novel was set across three different historical time periods, and there were two recurrences of the birds, one in the 1940s and one in the present day. As it turned out, I wasn’t very interested in the other two sections, and once I started writing, I knew pretty quickly there was no way the school would survive the events happening in 1871—and even if it did, the novel would be 700 pages long. So I ended up focusing on just this one time period, but the birds were there before the novel was anything like itself.

With reviews, sometimes you receive criticism and think, “Maybe that is true?” But occasionally a comment just feels like it’s about a different kind of book than the one I wanted to write. Some readers really want a book to be either realism or surrealism. Where I tend to live as a writer is in this weird foggy zone between those two, where realism is stretched, bent, intensified. That’s where I find the spark, as a writer.

ST: I personally loved the fabulist element of the trilling hearts, with their girl-shaped nest that contains, among other things, a fingernail, a human tooth, and a rag soaked in brown-red blood. The nest resembled, to me, an ovarian teratoma—a type of ovarian tumor that has been known to grow skin, muscle, bone, and hair. Was that something you were thinking about?

CB: The birds are very connected to the girls’ bodies. They’re stealing little bits of the girls, and it’s one more really loud insistence that the people running the school cannot pretend the bodies of these girls don’t exist. They are not genderless minds. Their bodies are real things, whether or not the men want to look at them. I don’t think I had consciously gone as far as thinking of the nests as teratomas, but I certainly had this image of them being an assemblage of little bits of bodily things, constructed from pieces of the girls.

ST: There’s this moment when Eliza first arrives and she overshares with the other girls. Caroline wonders if she’s seeking attention or if she’s simply hoping that “if she met Trilling Heart with her entire self in her hands, it would give her its entire self in return.” There’s a vulnerability there, but you get the sense that after her encounter with the school, she’ll never be able to get that vulnerability back. Do you think you’ll revisit what happens to Eliza in some future work?

CB: This is a matter of taste in fiction, but I think a good ending has to have things it leaves you wondering about. The book has question marks that, I hope, live on in people’s heads. I don’t want you to feel at the end that you can stop worrying.

I think some readers will be frustrated that I didn’t fast-forward 20 years and tell about Eliza’s marriage and so on, but for me, there’s a certain kind of aesthetic satisfaction, or maybe just truth, in not knowing how everything is going to turn out.

ST: What was your writing process like?

CB: I started The Illness Lesson in 2012 and had a draft in 2014.At the time, I was parenting a small child and editing my story collection, and during the years that followed, I had a second baby and my story collection came out.

Then, in early 2018, I ended up with a semester with no teaching, not entirely by choice; I had been doing a bunch of adjuncting and they didn’t have a class for me. At the same time, I received a grant from the Sustainable Arts Foundation, which is an amazing organization that supports creative work by parents. The grant was almost as much as I would have made adjuncting. My husband and I had two children, so we had to sit down and ask, “Can we carve out this time as a family?”

My husband’s job is much more structured, and his is also the job that gives us health insurance. If yours is not the job that provides that, you’re usually the one to take the kid with pink eye to the doctor or meet the person who comes to fix the furnace. We made the decision that, for three months, that would not be me.

It’s tough to write a novel during the phase of life that is early parenthood. With a story, you can get the whole thing in your head pretty easily. With a novel, you don’t always need to have the whole thing in your head, but for the big overhaul-type stuff, you do need to understand how all the parts are talking to each other. To do that, I needed to be working on it really intensively every day. I really did need that burst of time, and it turned out to be enough. My brain had been working on it all those years.