Books & Culture

The Quiet Death of Privacy in “The Circle”

The adaptation of Dave Eggers’ novel nails the insidious rhetoric of Silicon Valley

The Circle, the large communications conglomerate from which James Ponsoldt’s film gets its name, is all about sleek surfaces and minimal design. When Mae (Emma Watson) first lands a job at the California company’s Google-esque compound, she’s greeted by glass buildings, open-concept office spaces, and desks that only house screens and keyboards. Just as its product TruYou helped to declutter the digital footprint of its users — integrating social media profiles, payment systems, email addresses, and “every last tool and manifestation of [people’s] interests” into one central account — The Circle’s campus is likewise a study in simplicity. In transparency, even.

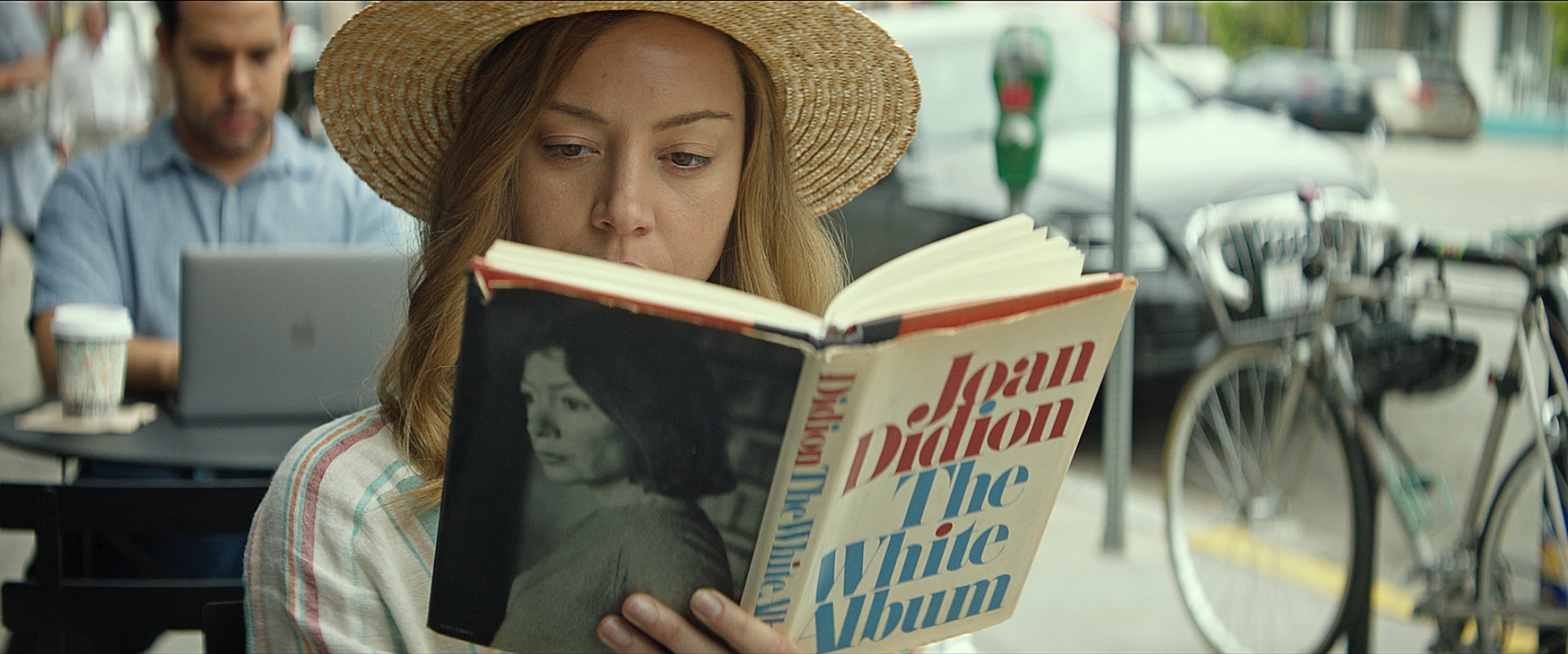

Keeping with the Dave Eggers’ novel on which The Circle is based, Ponsoldt’s film follows Mae as she rises within the company’s ranks. She begins as a lowly “Customer Experience” (CE for short) rep. A newbie to the world of zinging and smiling (think tweeting and liking), Mae quickly masters the many screens she’s encouraged to oversee at her CE job (including her phone, a tablet, and three monitors at her desk, all of which keep her abreast of customer complaints, social events on campus, and conversations happening across the company) before she immerses herself in her corporation’s mission to “close the circle” and, in the PR-ready lingo of The Circle, “reach completion.” As it turns out, this means imagining a world in which Circle users are constantly being surveilled.

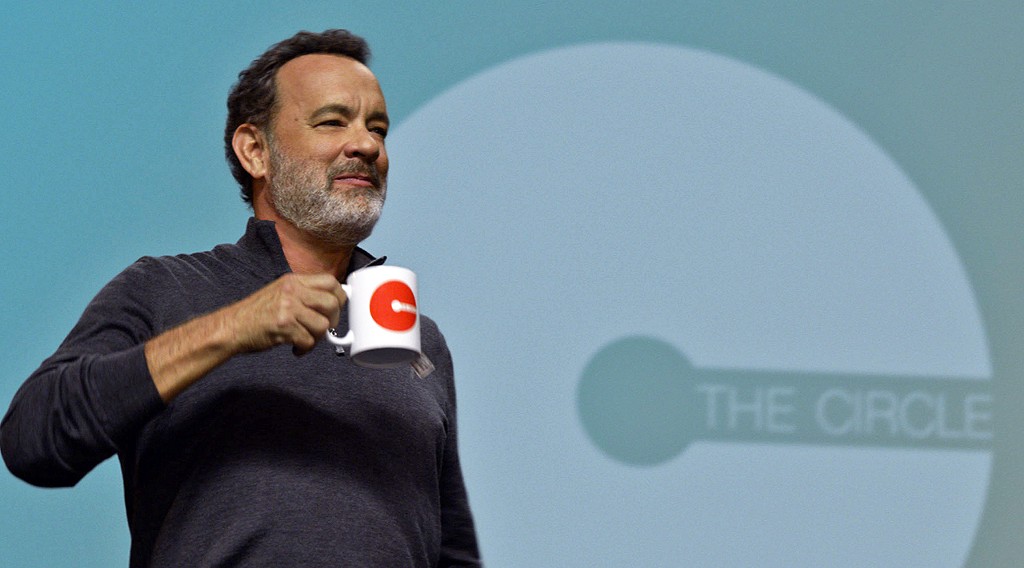

Eamon Bailey (Tom Hanks), one of the three men who first founded The Circle, states his aims bluntly in the film: “Knowing is good. But knowing everything is better.” Upon introducing their new product, a small HD camera that can be easily and wirelessly installed anywhere in the world (imagine logging on to check out the waves at your favorite surfing beach! Or having access to your apartment’s closed circuit cameras at the tip of your fingers!), Bailey recruits Mae to be the first Circler to go fully transparent: donning the SeeChange camera around the clock, thereby giving millions of viewers a front row seat to her entire life.

Injury by Proxy: Why “The Handmaid’s Tale” Is So Painful to Watch

Clearly, Eggers’ premise was aimed at litigating some of the darker consequences to our oversharing digital economy. For every minute connection one might feel posting on social media or communicating with someone on the other side of the world, Eggers provocatively showed the many freedoms simultaneously being relinquished. When we first meet Mae in the film, she is blissfully kayaking by herself. This is an activity that later will bring her grief from her coworkers, who can’t fathom her never posting anything from these trips alone. In their estimation, not only is she depriving herself of ways to mingle and meet people with a similar interest, she’s robbing her worldwide followers the chance to experience her peaceful kayak mornings. It’s all a bit too blunt — and that’s even before Eggers ties Mae’s ambivalence about The Circle to the various sexual encounters she has with men, each a stand-in for the different ways of relating in The Circle’s world.

In moving to the big screen Ponsoldt wisely sidesteps these tricky erotic encounters. Instead, Mae becomes more of an active agent in her own narrative, leaving room for the director to nail the ripe-for-self-parody moments at the start of the film, as the young ingénue first navigates her new workplace. If the adaptation of The Circle falters at all it’s in the shared shortcomings that beset Eggers’ technophobic manifesto. Mae’s descent into a wholehearted belief in The Circle’s autocratic policies feels all too tidy, more a way for Eggers to make his overarching point than an investment in a believable character arc. Still, depicting an all-too-plausible dystopia, the film manages to perfectly skewer Silicon Valley’s (ab)use of language when it comes to the commodification and dismantling of individual privacy.

“With the technology available,” Bailey says at one point in the novel,

communication should never be in doubt. Understanding should never be out of reach or anything but clear. It’s what we do here. You might say it’s the mission of the company — it’s an obsession of mine, anyway. Communication. Understanding. Clarity.

It’s one of the many moments where Bailey’s (and The Circle’s) rhetoric is so farcically self-serving that you wonder how Mae — or any of her coworkers, let alone their customers — doesn’t see right through it. The blatant obfuscation mostly goes unremarked in the novel and film, though Hanks, doing his best Gates/Jobs/Zuckerberg impression, makes Bailey’s speeches more convincing than they are in the text. For those at The Circle, his slickly expressed ideas feel intuitively correct, like thoughts they’ve had but never felt compelled to articulate. The presentations, breathlessly anticipated by those in the company — playing in the film like a mix of an Apple keynote speech and a TED talk — get at the way that contemporary digital branding pushes language and logic to a near breaking point. When we hear Circlers advocate for “clarity” and transparency, what they’re in fact proposing is the dissolution of personal privacy, a sleight of hand central to the insidious Silicon Valley rhetoric that both Eggers and Ponsoldt stridently call out.

In the presentation when Bailey announces that Mae will go transparent, he has them restage one of their earlier conversations. He wants to walk the audience through what had led Mae to make revelations crucial to the future of his company. But, in presenting them he reduces her ideas to epigrammatic one-liners, of the type you’d find in a Hallmark card or on an inspirational poster. Or, in the marketing copy of The Circle’s advertising:

SECRETS ARE LIES

SHARING IS CARING

PRIVACY IS THEFT

The sharing economy on which the company’s philosophy rests (as well, crucially, as their bottom line) is one that leaves no room for secrets. Bailey is a man who earnestly asks “What if we all behaved as if we were being watched?” while trying to make that panopticon-like proposition seem desirable. The implicit moralism of his pronouncements — which go unquestioned by the world at large and ultimately drives Mae to inexplicably abandon her need for privacy, to instead champion transparency at all costs — is what makes at least the message of Eggers’ text so astute, despite the awkward bluntness of its execution. The film ends up playing like a supbar Black Mirror episode, where a tyrannical dystopia becomes, in Mae’s eyes, blissfully utopic: “a glorious openness, a world of perpetual light,” as she puts it in the novel. But it still gives us a fascinating Orwellian riff on Silicon Valley — only, instead of the thought-limiting language of newspeak what we get are platitudes that seem utterly benign.