Books & Culture

The Real Villain in Netflix’s ‘Alias Grace’ Is the Male Gaze

The adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s novel shows that the story’s real horror is women’s constant surveillance by men

“And it fell out, as they watched a fit time…she was desirous to wash herself in the garden: for it was hot. And there was no body there save the two elders, that had hid themselves, and watched her.” — Susanna 1:15–16, King James Bible

Alias Grace knows Susanna and the Elders was a horror story.

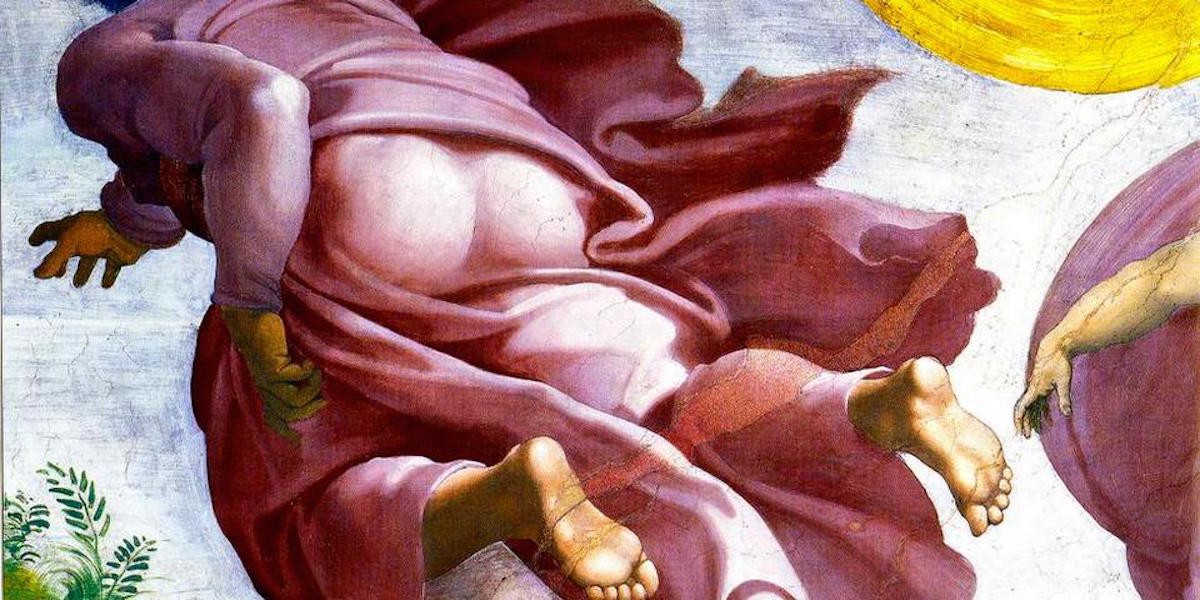

When the protagonist, Grace Marks, sees Guido Reni’s painting in the home of her employer, Thomas Kinnear, she’s fascinated but unsettled; her eyes keep sliding back to the recoiling figure of Susanna..The suave Mr. Kinnear suggests it’s frightening because a woman was falsely accused of a grave crime, and only the intervention of a clever man saved her. Grace, his maid (and later, murderer), listens politely to this foreshadowing. But when she looks at the painting itself, Grace is clearly troubled by something deeper. Kinnear’s retelling, which barely mentions Susanna, has done nothing to explain what’s actually so unsettling about Susanna recoiling from the men who came upon her when she thought she was alone. Grace doesn’t yet understand that the horror of the story is that women are always being watched.

The novel by Margaret Atwood centers on real-life crime celebrity Grace Marks, convicted in 1843 of murdering Thomas Kinnear, and possibly the housekeeper Nancy. Its character study unspools with the deliberate dread of a psychological thriller, with Grace gently pulling (fictional) psychiatrist Dr. Jordan through a story that suggests no matter who struck the fatal blow, patriarchy is the monster behind the crime.

Netflix’s recent Alias Grace, written by Sarah Polley, makes the most of this villain. Despite some stylistic flourishes, the series keeps its central focus on Grace’s struggle against the inexorable, banal horror all around her; patriarchy is frightening not because men can torment you, but because most men think nothing of tormenting you. Grace (Sarah Gadon) often asks questions she doesn’t answer, because the truth is both so obvious and so disheartening. Men behave monstrously because they can. Women believe men love them because the other option is to buckle under the weight of the truth. Women must think about men every second of the day, while men can get away with thinking about women so little that Dr. Jordan (Edward Holcroft) has to ask what goes into household chores.

What makes Grace an uncanny rather than a tragic figure is the control she exerts in the telling. Half the satisfaction of her interviews is seeing what scraps she keeps away from Dr. Jordan’s prying eyes. And as she presents her unanswered questions to Dr. Jordan, he is, inch by inch, forced to answer them himself. Director Mary Harron is most famous for the kinetic frustration of I Shot Andy Warhol and the hyper-aware dread of American Psycho, and here she seeks to deconstruct them both; with every shot, Alias Grace demands that we think about what makes a horror movie.

To say “male gaze” is something of a shortcut; it suggests a monolith where the reality is often more nuanced. But the idea of patriarchal norms as an unconscious, poisonous force is highly present in Atwood’s work. Its most direct distillation might be The Robber Bride: “Even pretending you aren’t catering to male fantasies is a male fantasy: pretending you’re unseen, pretending you have a life of your own, that you can wash your feet and comb your hair unconscious of the ever-present watcher peering through the keyhole, peering through the keyhole in your own head, if nowhere else. You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.” What better way to describe the camera?

The camera is inherently a vehicle of suspense; to watch anything on film is to be waiting for something to happen. But the camera is far from a neutral observer. Harron knows it; familiar tricks of the horror genre are presented in a way that forces us to consider how we accept the camera’s gaze on women, and the violence it implies. In horror, anticipating the violence is both a source of suspense and of perverse glee (perfected in American Psycho). Either she’ll survive, or the monster will get her in the end, and either one is entertaining. (The fact that Grace is the subject of the violence, rather than the object, is one of the many things that makes the usual visual beats so discomfiting.) Within the narrative, Grace constructs her story for her male audience; in the intimacy between Grace and the viewers, Harron’s camera asks what we take for granted.

Within the narrative, Grace constructs her story for her male audience; in the intimacy between Grace and the viewers, the camera asks what we take for granted.

The show deliberately structures itself around the monster in the room. Conversations between women are almost exclusively about men — even beloved Mary speaks more often of her political hero or the son of the house than about herself, or about Grace. (Grace would have nothing to tell that wasn’t about a man, anyway. Her dead mother is already a footnote; her father abused her, then demanded she send money home.) And if anyone in the room speaks about another woman, it’s usually on the binary of whether or not she’s made herself available for sex. Why, Grace almost asks but doesn’t need to answer, is women’s currency of reputation designed to be so easy to bankrupt?

Even the things we’re meant to look at suffer from the great divide. Much is made of quilting, Grace’s favored craft, and so far removed from Dr. Jordan’s experience that the moments she talks about it play like a codebreaking scene in a spy movie. It’s not an art men are meant to understand; it’s a warning from women to women about the inescapable. The only other piece of art we see is Susanna and the Elders, a striking painting whose story Mr. Kinnear is only too happy to explain — and why would you need more than that, when that’s the only story possible for a woman?

Injury by Proxy: Why “The Handmaid’s Tale” Is So Painful to Watch

Harron’s visuals draw us back and back again to these unspeakable answers. Grace’s first position at the Parkinsons’, with Mary, has the soft-focus flatness of a story being forced into something happy; later, the Kinnear house is lit with the same encroaching shadows as the painting of Susanna. And in the frame-story parlor, Grace is bathed in beatific light that we know is Dr. Jordan’s doing. It’s the same light as his daydreams of rescuing her — standard, even expected, story beats that have been so quietly debunked by the camera that instead of romantic, they land halfway between laughable and invasive. In these daydreams, he never rescues her from the handsy guards or heroically demands her freedom in a busy courtroom; he always comes upon her when she’s alone.

But even his increasing uncertainty about Grace’s role in the murders doesn’t stop him from having these dreams — from focusing his wide-pupiled attention on her, from inching toward her until their knees are married, from trying to trick her into giving up the key that will let him understand her and be done. Given how much of the series rests on this claustrophobic rhythm, it’s remarkable how effective it always is to cut from Grace’s carefully-arranged features to the Doctor’s vampiric attention — an old-fashioned horror beat that works very, very well.

Support Electric Lit: Become a Member!

And Grace knows. Sarah Gadon deftly threads the needle of both Grace’s slyness and her melancholy, and though some specifics of Grace’s confinement are glossed over, the implication is clear: she has gotten on in life in direct relationship to her ability to navigate what men want. Even alone, Grace is observing herself; in her cell at night, she constructs her own life from the outside, quick-cuts of alternate explanations and angles. When she takes the fateful nap in the Kinnear’s meadow, speaking to the doctor of her solitude, she paints the Doctor a quiet mockery of pastoral melancholy, and then — more honestly — imagines herself from behind, watched by farmhand Jamie. It’s a horror-movie shot, and a moment of quiet tragedy from a Grace who knows better. (Without quite meaning to be a monster, Jamie does, in fact, get her in the end.)

In Alias Grace, patriarchy isn’t just men taking advantage of women without consequence. It’s the only thing that shapes Grace at all, and Polley and Harron let us linger in how wholly it’s become the gaze Grace turns on herself — so unforgiving, angry, and powerless she can’t remember the moment she broke beneath it. It means everyone is possessed by the same demon that no one can exorcise. It’s a horror so pervasive and unimaginable that a glimpse of its true power drives Doctor Jordan mad. (He goes to war rather than think about it; back home, his nerves shot, Grace consumes him.) Outside of the male gaze, Grace as we know her doesn’t exist, and the idea of a Grace without it is the ghost that haunts her.

Outside of the male gaze, Grace as we know her doesn’t exist, and the idea of a Grace without it is the ghost that haunts her.

There are few victories in this story; half the horror of having the patriarchy as your villain is that the monster’s almost bound to win. The Doctor never writes his letter. Mary and Nancy meet sorry ends. Grace doesn’t even get to name her righteous anger and claim the murders — either it was Mary after all, or she’s clever enough to give Mary credit. (That scene, with its widow’s weeds, is both the height of the series’ uncanny affect, and the stripped-bare truth of Grace as object. Even those agitating for her freedom have a matinee-audience detachment about her suffering.) By this point, Harron’s camera has made us painfully aware of the horror of being looked at, of the idea that women are constructed of wounds men leave behind. Grace is not herself, because without men, she can’t be; this itself is murder by a thousand cuts, right before our eyes.

Traditionally, if the girl in a horror movie survives to the end, there’s one last scare — the killer glimpsed again, a prophetic nightmare, the stomach-dropping reveal that the evil has spread — to remind us that horror is the constant of life, not the interruption. It’s fitting that this horror belongs to Dr. Jordan, and not to Grace. The last time Dr. Jordan sees her she’s merely looking back at him, but Harron frames it like the last horrible discovery in a thriller: the corpse of the person you thought was far from the danger, the demon that survived the exorcism after all. Hers is a look that knows what lies ahead for him.

Half the horror of having the patriarchy as your villain is that the monster’s almost bound to win.

For Grace, things are quieter, both because she’s already at the center of the story’s violence (overt and otherwise), and because she knows this is a demon that can’t be conquered, only bargained with. And so our reassurance, such as it is, is that Grace makes her peace. Harron’s camera leaves the claustrophobic close-ups of the parlor, at a respectful distance as she wanders her farm and hangs a quilt of her own in the same flatly unreal light of her early happiness, quiet and unobserved. She’s sufficiently outdone the men who sought to fathom her; they’re diminished by trying (the doctor and Jamie both). And at the last she looks out at us — for once, the examiner.