Books & Culture

The Sounds of Madness: The Subprimes by Karl Taro Greenfeld

by Kurt Baumeister

“The Necropastoral is a political-aesthetic zone in which the fact of mankind’s depredations cannot be separated from an experience of ‘nature’ which is poisoned, mutated, aberrant, spectacular, full of ill effects and affects.” –Joyelle McSweeney

In our world, one in which images of impending environmental doom seem to simmer and bubble all around us — hapless polar bears on melting icebergs, seagulls slicked black with spilled oil, withering farmland and flooded cities — McSweeney’s concept of the necropastoral is at once intellectually vital and darkly comic. On its most basic level the term is ironic, a sort of Latinate, literary shorthand for man’s fundamentally flawed relationship with his planet, a marker for his simultaneous roles as victim and perpetrator, maker and reaper, of apocalypse. It’s also a term that seems uniquely descriptive of Karl Taro Greenfeld’s second novel, The Subprimes. Others would be infectious and breakneck, hilarious and profound.

The latest addition to the growing subgenre of cli-fi (or climate fiction), Greenfeld’s is one of, if not the best. Part satire, part preemptive elegy for a dying planet — and, really, who will be around to write (or read) an elegy if the unthinkable becomes reality? — The Subprimes may turn out to be one of 2015’s most-celebrated novels. With a language that splits the difference between Martin Amis’s slangy poetics and Vonnegut’s jabbing minimalism, more heart than any piece of comic writing I’ve ever read, and a narrative twist or three up its black little sleeves, The Subprimes is the work of a major, emerging talent in literary fiction.

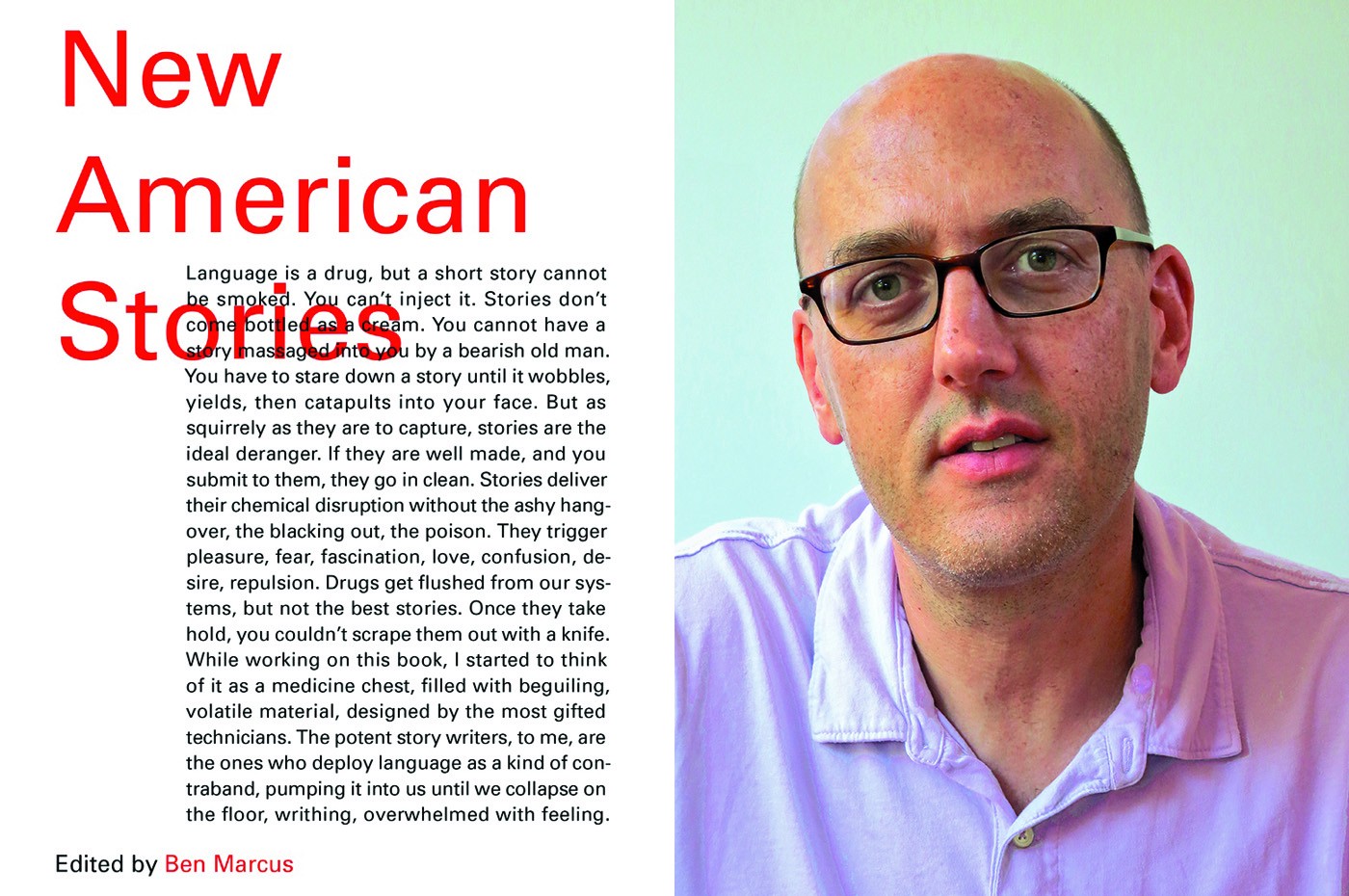

I feel a little silly describing Greenfeld as an “emerging talent.” He’s published six books of nonfiction after all, written for The New York Times, GQ, and Vogue, and placed stories in the Best American Short Story series twice (2009 and 2013). Still, this is only his second novel. His first, Triburbia (2012), was a critical success Jay McInerney (writing for The New York Times) called “artful” and Publishers Weekly described as “absorbing.” So, I’ll stick with “emerging.” Fair is fair.

The subprimes are average Americans in a near future that may become our own, a growing class of people with bad credit and worse job prospects edged out by the unfeeling (often insidious) forces of killer technology and market economics run amok. In an America that’s fracked its way to energy independence (and become the world’s largest energy producer as a result), families of dispossessed subprimes roam the American countryside in their beat-up, gas-guzzling SUV’s, postmodern Bedouins trapped in an American Nightmare.

The book’s main character (and narrator) is Richie Schwab, a dope smoking, middle-aged hack journalist. Richie’s dual role as reporter and story reminds me of the great, vaguely meta-fictional narrators Martin Amis used in his best novels (the London Trilogy of Money, London Fields, and The Information). A stand-in for the author himself, Richie’s role in both first and third person narrations plays with notions of truth and story, the lines between fact and fiction.

In addition to Richie, the cast is made up primarily of families: one of subprimes (Bailey, her husband Jeb, and their children, Tom and Vanessa), another in danger of becoming subprimes (Gemma, estranged wife of fraudulent energy derivatives trader, Arthur Mack, and her daughters, Franny and Ginny), and Richie’s own (his ex-wife Anya and their kids, Ronin and Jinx). There are two notable exceptions, both spiritual leaders of a sort: Sargam, a young woman who eventually becomes the leader of the subprime community at the center of the book’s drama, and televangelist Pastor Roger, leader of the famed Freedom Prairie Church (and pawn of wealthy industrialists, the Pepper Sisters). Though this list of characters may seem dizzying in the abstract, there’s never trouble keeping them all straight. The book is a smooth speedy read, one that nonetheless has a lot to say.

As the power of government yields to that of the corporation, the subprimes find themselves constantly on the run, moving from one Ryanville (camps reminiscent of the Hoovervilles of the Great Depression) to the next. There, they work wage-unregulated jobs (the minimum wage having been outlawed) at job sites unpoliced by the Feds (OSHA and the EPA, too, have gone the way of big government). It’s not only humanity that suffers in Greenfeld’s world: from whales mysteriously (maybe suicidally) beaching themselves to roving packs of ravenous coyotes and the blasted vistas left by industry run rampant, nature is in open rebellion against humanity in general and America in particular. With global warming accelerating, the wealthy plot their escapes to sanctuary islands where they dream of living untouched by the death all around them. Though they never come out and call themselves “primes,” the derision we hear leveled at the jobless, credit-unworthy subprimes carries echoes of the alphabetic caste system of Huxley’s Brave New World.

At the heart of Greenfeld’s future America rests the abandoned town of Valence, Nevada, an arena in which good and evil (or, better put, life and death) will meet in the forms of Sargam, Pastor Roger, and their respective flocks. Under the cyanide gaze of network news drones (and unintentionally-embedded journalist, Richie Schwab), Pastor Roger’s quest to bless the Pepper Sisters’ latest tool of resource extraction, the massive Joshua machine, will come up against Sargam’s philosophies of nonviolence and “people helping people.”

There will be losses on both sides, the worst of them born by children, which is one of the central points Greenfeld posits: humanity’s relationship with its environment is so unsustainable that it amounts to the rejection of a future beyond that which we can see and, on some level, the rejection of life. Couple this with the role of the supernatural in the book’s conclusion (earned though it is throughout) and we have the final piece of Greenfeld’s satire. In a world so clearly stripped of magic — so obviously a result of the victory of technology over everything including man — the idea of humanity being saved by supernatural means is laughable, no matter how good it might feel dramatically. In the wake of Greenfeld’s last, and maybe his darkest joke, the reader is left with two choices — either stop laughing altogether or laugh loud enough to drown out the sounds of madness all around you.

by Karl Taro Greenfeld