interviews

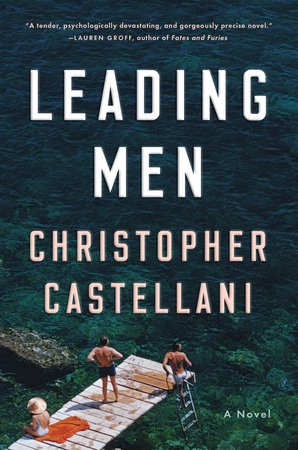

The Tennessee Williams The World Never Sees

Christopher Castellani’s “Leading Men” looks at a “missing week” in the playwright’s relationship with his partner Frank Merlo

As fiction continues to push itself in terms of story and structure, some of the best novels look back in history for a way to understand where we are as a society and where we are headed. Christopher Castellani has a knack for finding what he calls cracks in history that allows him to find new stories to tell about underrepresented historical characters.

In his latest novel, Leading Men, the author envisions a “missing week” he discovered in the journal of Tennessee Williams. It was during his time in Italy with his partner Frank Merlo. While many authors lives have been fictionally retold over the years, Tennessee Williams’s life has remained largely untouched. Castellani explores the playwright’s romance with a working-class man and questions what keeps people together and what tears them apart.

Throughout the novel, which takes place in 1953 Italy as well as a decade later while Frank Merlo is dying, readers get an insight into Tennessee Williams that expands the lens on the works he wrote and who inspired them.

I spoke with Christopher Castellani about reimagining the lives of historical figures, writing a gay romance just like any straight romance, and why certain stories are passed on by the film and publishing industry.

Adam Vitcavage: What about Tennessee Williams made him interesting as a character for you?

Christopher Castellani: I really like a tell-all memoir. I came across one in the late ’90s by Dotson Rader called Cry of the Heart. I knew who Tennessee Williams was from high school. I wasn’t a huge fan necessarily but I remember liking his sensibility. I read the memoir of the great American playwright in the 20th century who had this working class Italian partner from Jersey. I was a working class Italian dude from Delaware. I wanted to know how those two ended up together.

Frank Merlo was his partner during Tennessee Williams’s most successful years. When Merlo was dying, Williams wouldn’t visit him. After Merlo had died, Williams never had another commercially successful play.

I read all of that and became obsessed with those two men and what about their relationship made Tennessee Williams so successful. As much as I love Tennessee Williams, it really became about Frank Merlo for me.

When Merlo was dying, Williams wouldn’t visit him. After Merlo had died, Williams never had another commercially successful play.

AV: You’ve written a few books now and most of them are set in a historical context. What entices you to go back in time to write?

CC: It’s funny, with all of my novels, I never made a conscious choice to write historical fiction. I didn’t have any goals of wanting to see how that time period was or how history was repeating itself. I was more drawn to characters who happen to exist in those times. The question is why those characters thrill me more than contemporary characters.

I have four novels and three of them are set during World War II or the 1950s. One thing I love about historical fiction is that in the research process you come across such rich material. It makes you feel grounded in the time and gives constraints of what you can and can’t do. I need those constraints to focus on what I really want to focus on.

With this novel, I had so much material about Tennessee Williams, Frank Merlo, and Italy in the 1950s. I didn’t want to write anything about these real people that couldn’t have happened to them. I wanted to write in the cracks of what we knew and might have happened. Having those constraints of what actually happened allowed me to find the fictional cracks.

In Williams’s journal, which was very meticulous in certain ways, there is a week in July of 1953 where there are no entries. It was during a very contentious and eventual summer. There was the crack. I took everything I knew about him, Merlo, and Italy, and tried to figure out what happened during that missing week.

AV: After you learned about Frank Merlo, did you see any of him in Tennessee Williams’s plays?

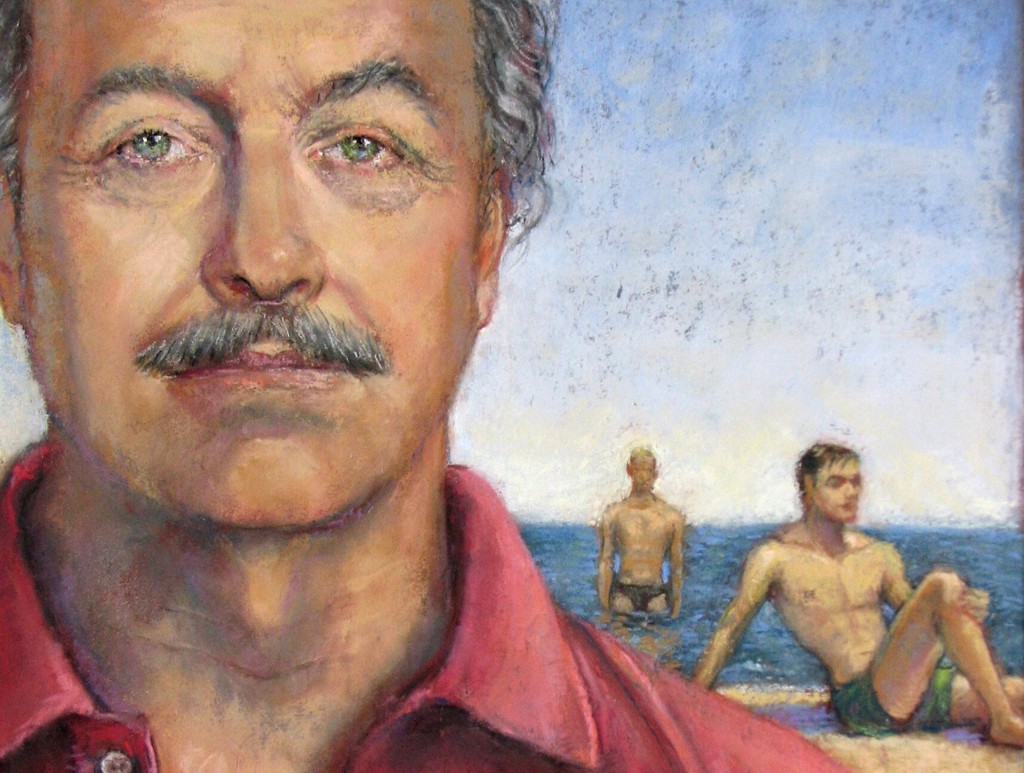

CC: What was interesting is that Williams said Merlo was what tied him down to Earth. Merlo was more a part of his process than his product. There are certain examples of when Merlo shows up in plays. There is a play called The Rose Tattoo which is the only play with a character based on Frank Merlo that Williams wrote that was wildly successful. The character Alvaro Mangiacavallo was, by Williams’s own account, was very much inspired by Merlo. It was set in Sicily, it has a broodish, handsome, working-class guy in the middle of it. He represented love and passion. That was the Merlo that inspired Williams’s work in terms of the product.

In terms of the process, he tied him to Earth. Merlo arranged all of their travel, he took care of their clothes, he took care of Williams’s medication, he talked him down. He did all of the things a partner of a writer does when the writer can’t do it. Williams had a hard time managing the ins and outs of daily life. Dealing with his own failures and insecurities, his terrible hypochondria, and how neurotic he was. Merlo was the opposite. He was perceived as happy-go-lucky. He was very engaging, very social, and very warm.

AV: As I was reading Leading Men, I realized I know absolutely nothing about Tennessee Williams other than the plays he wrote. I find that interesting because he is taught in high school and revered as this important literary figure. He seems ripe for fictionalization though. Were there other stories or plays about him? Like Phillip Seymour Hoffman won an Oscar for Capote. Where is the Hollywood Tennessee Williams story?

CC: There are some plays about him. There is an adaptation of part of the memoir I mentioned, Cry of the Heart, that tried to get to Broadway. It may be coming though. It starred Al Pacino and started out in California. They were trying to retool it. It is called God Looked Away.

There have been plays that have taken on Williams as a character. I saw one a few months ago in New York that imagined his life around the time of The Glass Menagerie. It imagines his relationship between him and another playwright. There are a few plays like that that are two or three man plays. There aren’t any novels though. There aren’t any major books other than biographies.

Both Truman Capote and Tennessee Williams had the same trajectory. They were famous and revered for their art, but then both fell apart and succumbed to drugs and alcohol.

AV: That’s so baffling to me because what I have learned through your novel and talking to you is that he is ripe for sensationalizing and fictionalizing. I’m sure there isn’t some grand conspiracy against Tennessee Williams, but is there?

CC: It’s very interesting. I think Truman Capote was the more glamorous figure of the two and you already mentioned Capote, but there was even another movie that came out at the same time called Infamous. Both Capote and Williams had the same trajectory. They were famous and revered for their art, but then both fell apart and succumbed to drugs and alcohol. They became shadows of themselves. Perhaps Hollywood feels they have already seen that story.

Even though Williams traveled in glamorous circles, he worked. He worked every day. In the twenty years after Merlo died, he wrote every single day. He was a part of hundreds and hundreds of productions of his work. Despite his addictions and anxieties, he was still involved. Maybe that isn’t as exciting of a story.

I am frankly surprised no one has fictionalized on his life. It’s so compelling. I was going to say maybe it is that gay thing because there isn’t a glamorous female lead in the story. Even Capote had Harper Lee as a character.

AV: You tapped into something though. Capote came out and Hollywood feels the general public got their fix. They gave the gay writer story. Hollywood feels we only need one. Yet there are dozens of movies about a middle-class white guy in their thirties overcoming a childhood trauma of falling off their bike. I joke, but if you pay attention to Hollywood production news, you’ll see how a black director or writer saying a studio passed on their project because the studio felt they already checked off that box for the year.

Minorities, whether it’s race, ethnic, sexual orientation, are still having their projects passed on.

CC: That’s exactly right. It happens with publishers all of the time. A writer will pass on their work and an editor will say very frankly that they already have the Indian novel, or the gay novel, or the black novel.

A writer will pass on their work and an editor will say very frankly that they already have the Indian novel, or the gay novel, or the black novel.

AV: Then there are stories like yours. I feel it unlocked a lot of history that isn’t taught or talked about enough. There has been a recent trend of using historical characters to explore themes.

CC: There is a long history of it. Some people call it real name fiction, some call it alternative fiction, counterfactual history fiction. We take real people as characters. It started with political roots. People wrote these alternative histories as a way to indite the current moment to show a previous moment in history to comment on the current moment. Books like Phillip Roth’s The Plot Against America that had a very political angle are what I am talking about.

Maybe in the past twenty years, there have been these books that take public figures as central characters. Some of those books I used as a model for my own: The Master by Colm Tóibín about Henry James and The Hours by Michael Cunningham which featured Virginia Woolf. Then there was The Book of Salt by Monique Truong. What’s really cool about that book is the author found a scrap that was a throwaway line where Gertrude Stein makes reference to their Vietnamese cook. Monique Truong wrote an entire book about Stein from the perspective of the cook. She imagined a whole history.

Those types of creative endeavors are what interests me. They give a new perspective on a writer whose work can speak for itself but having another lens on how they conceived their work and lived their lives amplifies their work. It gives readers a new way into a writer’s work.

AV: It all goes back to finding those cracks to explore stories that are compelling.

CC: Exactly. Biographies provide a certain way of amplifying a writer’s life. Fiction in which a character lives and breathes, in which they hurt or are hurt by other characters, gives different light to the character. There is a greater intimacy than a biography. Or at least the illusion of it.

You’re imagining a writer who spent their life imagining other people.

There are no stories of Tennessee Williams and Frank Merlo being harassed or bashed for being gay in this novel.

AV: Through your time imagining and writing about Tennessee Williams and Frank Merlo, what did you learn about our current time in history?

CC: We are in an interesting moment. If this book is political, it’s political in the sense of how it depicts this relationship. It was an open relationship. It was a relationship that didn’t have any models in terms of marriage other than heterosexual marriage. They were figuring out what it meant to be in terms of partners, though they never used that term, of course. They were figuring out what fidelity meant. They were in a sense defining what a relationship was in a way that they could.

Now we are in the marriage equality era. I am seeing how many people I know in same-sex relationships are still defining and redefining what it means to be a same-sex partner even though marriage is the law of the land. Same-sex marriage didn’t eliminate the need for same-sex couples to figure out what their relationship is and defining their roles with one another.

You can argue that everything has changed and nothing has changed in terms of same-sex relationships. It’s potentially more confusing now because we have a model of traditional heterosexual marriage that doesn’t actually work in most cases for same-sex couples.

Tennessee and Frank weren’t hiding among their friends. Everyone knew he was gay and had a partner. As time went on in the 1960s, 1970s, and then the AIDS epidemic, celebrities went into the closet. Tennessee and Frank lived in an easier time because their sexuality was less visible. There are no stories of them being harassed or bashed for being gay in this novel.

AV: Which is important for queer literature. Not every story needs to be about harassment and overcoming adversity. There can just be a gay romance just like any straight romance that has been written about.

CC: Exactly. I mean, Frank Merlo’s story is tragic. He died young of lung cancer. The tragedy had nothing to do with his sexuality.