Books & Culture

The Transformative Power of Writing Trans Motherhood

How "Detransition, Baby" and "The Argonauts" illuminate my family's experience with pregnancy and transition

I see a pediatrician’s office late in my wife’s pregnancy, a get-to-know you ritual to assess our fit. A three-minute drive from our house, the location was perfect, but the vibes were weird, and it all came to a head with a question: did you use a donor? No, I said, he’s just ours, and the whole thing went sideways.

It was the third trimester, quickly approaching the I’ll be pregnant forever phase. My hair was up, no makeup, but I realized suddenly that she hadn’t clocked me, that I passed, and now she was deeply confused. It’s counterintuitive, how a less-femme face scrambles stereotypes. More fundamentally, people like us just don’t fit in that context, our reality was so far from her expectations; it didn’t occur to her that we could be what we are.

Well, I’m trans, I said. I described IVF, preservation, how we got here. Recognition broke, the pediatrician fumbled, tried to recover and fumbled again—we never got back to easy conversation. I wasn’t embarrassed, not mad, just tired. As much as people say they support second moms, they need this biological scaffold to make sense of it, those Xs and Ys, moms and dads. Our bodies as they seemed, together and making a third, just didn’t make sense.

The prospect of becoming a mom as a trans woman, of specifically creating a new little life after transition, often feels like writing on a blank page. We humans rely on stories to make sense of overwhelming change, not just as practical maps for planning and preparation, but to expand our horizons, to envision new possibility. Trans women receive endless stories, from inside and out, but most figure us anywhere else but here.

The prospect of becoming a mom as a trans woman, of specifically creating a new little life after transition, often feels like writing on a blank page.

Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby is a breakthrough in many respects. It’s a revelation for many trans women to see a major press novel with such unvarnished inside perspectives on trans realities in all their complication, muck, and mess. It has provocative intentions, taking on and breaking open some of our most difficult conversations, right from its title. For a trans mom, having recently gone through the process of childbirth and infancy, it was remarkable to see a book write so boldly into the white space around trans motherhood, suggesting a future with fuller stories for us to lean on, expanding our notions of what stories we can embody.

Ames, a trans person in Brooklyn who detransitioned after years of living as a trans woman, has done something he didn’t think possible: he has accidentally gotten his boss Katrina pregnant. Ames’s life in detransition, presenting as a man once again, had just settled into a groove, easy if detached and grey. Now everything is chaos again. While Ames may be able to stuff himself back into a shape like man, the prospect of father is too much to bear; no matter what face we put on it, Ames realizes, babies see through us. Desperate for stability, Ames approaches his ex-girlfriend Reese, a trans woman whose own need for motherhood has lead her through many strange paths and dead ends, and proposes a remarkable scheme: the three of them raise the child together. For Ames, having trans women who see him fully promises to keep him grounded as the needs of parent pull in new directions. Reese agrees, nominally to see a car crash up close, while struggling to contain a last hope that this might finally be real. Katrina, for her part, is knocked flat by revelations of Ames’s trans past and present, not to mention his plan, as a stable family just coming into focus is dashed again. But something in the scheme touches a need Katrina holds too, a discomfort with upright cishet narratives that corroded her past attempts at family. Against their better judgment, the three decide to see where it goes.

There’s audacity in reading pregnancy next to transition, particularly trans femme transition. There are of course so many lines to be careful of: avoiding appropriation, recognizing what is shared and what is not. There’s such political fire beneath it, these zealously guarded boundaries. But the symmetries and overlaps are impossible to deny⎯and there can be reciprocal value there, offering new language and perspective where traditional stories and boxes so often fail us. I think of Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, which famously reads her pregnancy alongside her partner Harry’s physical transition. How both processes can be like breaking through the ice, where true realities are much more complicated, messy and overwhelming than the stories we’re given. How the ways we are stigmatized and sanitized echo. How for all of us these processes of becoming reshape us and rebuild us, leaving us to wonder who we will be on the other side.

I see the bathroom where I knelt before my wife, my eyes at her navel. I pinched the skin on her belly, just as the video instructed. The syringe was ready. I’d never given a shot before, not to myself or anyone else, and we were both nervous as hell. It was astonishing how after so many years, after all we’d seen together, we could suddenly discover whole new intimacies, these new configurations of bodies, proximity and trust, control and purpose.

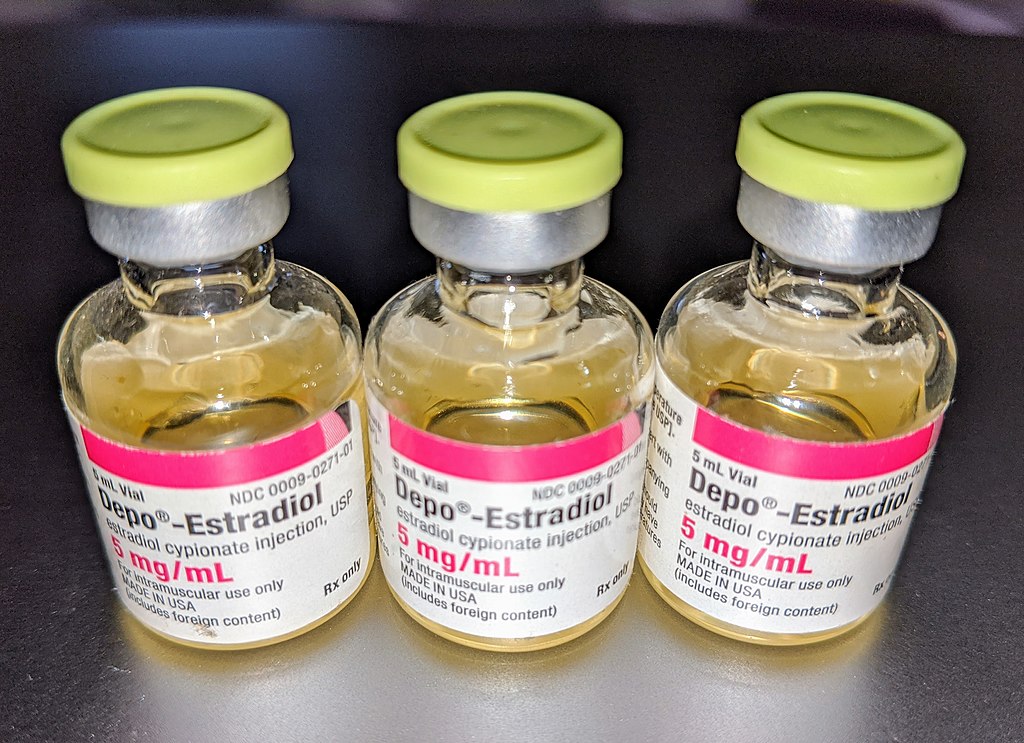

We agreed that I would handle the shots, three every day for that first month of the IVF cycle. Don’t be scared, the pharmacist said handing over giant draw needles, they look like they’re for a horse, but you don’t stick yourself with these. We took the package with wide eyes. Different shots had different formats: an injection pen in a green fabric case, prefilled syringes stored in the fridge, and these standard draw vials. The pharmacist also handed over a box of injection needles the size of a cigarette carton, one hundred in all, which held its own menace, suggesting a long haul, all the ways this could go wrong.

Nelson describes a similar scene as she sets her own pregnancy against her partner’s transition, the parallels of bodies in motion, their partnership of creation and becoming. After her Harry decides to go on T, she gives his shots, reflecting on the peace it brings and her own agency in it. “Each time I count the four rungs down on the blue ladder tattooed down your lower back, spread out the skin, and plunge the golden, oily T into deep muscle mass, I feel certain I am delivering a gift.”

The rebirth of our bodies is rarely a solitary act.

There is a specifically trans relationship in this space. The rebirth of our bodies is rarely a solitary act. Sometimes, it’s merely seeing someone else embody what we need, the possibility they open by living their own story. We receive stories that carry us from elders and family, from community, from mentors and doulas and midwives, books and GPs, endless fora where individual wisdom accretes to folk knowledge. But there is a particular connection when the means of transformation are literally in another’s hands.

The relationship of trans motherhood hangs all around Reese. So many of her own relationships in her trans community involve ties of trans motherhood, with lines often blurring between friendship, romance, and family. In this space, the specific motherhood in becoming has special weight. When people criticize her friend Thalia for an off-color joke at a funeral for another trans girl, Reese pulls rank. “Oh come on… you know who gave Tammi her first shot? Thalia. Right in the butt. Who are you to say if she can make a joke or not?” The point is clear: Thalia helped Tammi become Tammi in the most intimate terms. Their relationship is foundational, the bond beyond question.

On the first morning, it was just the two of us. The doctors sent a link to a bank of training videos, and I did my best. I never had a trans mom, had never done injections, instead placing two blue estrogen tabs my nurse practitioner prescribed under my tongue each morning and night. The videos all featured a woman alone, injecting herself, reflecting the isolation in this institutional, normative mother space. Each video started with a list of supplies, canned audio for each item, and the cadence of the voiceover reading sterile gauze looped through my head as I performed the ritual, swabbing vials and skin with alcohol, pulling oil into a barrel, swapping needles. My wife’s belly was pale and soft; it was familiar of course, but I’d never seen it quite like this. We marked the shots around her navel like hours on a clock, around and around, day by day. It was strange how all these changes devolved to a science problem: add hormones, and a body reads the instructions, responds, transforms.

Something familiar as we turned to the pregnancy process was the breadth of stories, how they suddenly came from everywhere. Once you are through that ice, you are overwhelmed by the realities of it, always more to know, always more to fear, and so much cannot be known until you are in it and living it. You are immediately sifting voices from every angle. There are doctors of course, as both transition and pregnancy have moved firmly into the medical world in the last 100 years. But so much comes from elsewhere; it’s often less about fact from fiction than instinct, grabbing what feels useful, letting fall what doesn’t.

Something familiar as we turned to the pregnancy process was the breadth of stories, how they suddenly came from everywhere.

Even with all this information, there were so many surprises. One night, about a year into transition, I came up behind my wife, and as she turned, my eyes missed her nose and met her chin instead. I stood against our bathroom doorframe with a carpenter’s triangle, like we did as kids, and marked my height: I’d lost an inch from HRT. On forums, half the girls said it was impossible, while the other half noted it had happened to them. Possible or not, I was now the short one. Late in the first trimester, we started to hear a lot about feet. Suddenly the conversation was everywhere—how they grow, how they change, not just the temporary swelling but permanently, forever. This hit my wife hard: hadn’t her borrowed shoes traced my first steps as a trans femme? Hadn’t she felt emboldened to appropriate my old clompy boy shoes, my black Chucks and Sambas, as she found space for her own newly-legible queerness?

Through the pregnancy, the stories I didn’t have became inscribed on my own body. As my wife gained weight, I kept pace. My face filled, my skin softened (don’t say glowed). My focus slipped, baby brain took hold. It’s difficult to describe these symmetries, acknowledging and respecting what is not shared, while facing what was real. I lacked any stories to properly hold what was happening to me—physically, in my own body—to confine or refine this sense of blurring. As her body changed in so many ways, mine shifted too.

In the flux space of pregnancy, I asked my NP about shots. Injectable hormones are so often held up in the folk wisdom, said to bring fuller embodiment. As a ritual, there is something so visceral and immediate to this act. Spending so much time with doctors, endless scans and hospital soap, I realized one day that my fear of needles was gone, replaced by an eagerness for agency, for control. The medical process of changing bodies was not just demystified, but there was momentum—a trans dynamic, that interplay of proximity and need. And after all, these shots would be the easy part. Sticking someone else, someone you love, is so much harder than taking control of yourself. As I watched my wife’s journey unfold, all the change she bore, this was nothing at all.

I insisted on shots in the belly. It wasn’t my NPs standard practice, but I pitched information scraped from community space with more members than any study, that accreted community wisdom. After doing her own homework, my NP agreed. I took that old green case and tore its guts out, remaking it as an injection kit, and stuffed it with supplies I learned from the training videos. The box of 100 needles was barely touched after our early success. Preparing for my first shot, alone in my bathroom, the cadence of sterile gauze still rang through my head.

For Reese, breastfeeding is a foregone conclusion. As they share more and more, as the bond of their mutual project deepens, Katrina is surprised to learn that trans women can breastfeed. Reese knows all about it, but in messy queer fashion her information came sideways. Her stories come from fetish space, from cis men living their own body anxiety through her body, knowing their own flesh had that potential too. And so this is how Reese came to own a manual pump already, a gift stuffed in a sock drawer.

Standing with Katrina in a bougie baby store, staring into a case of sleek baby-blue electric pumps, Reese wants to tell Katrina of the eroticism in motherhood. Even this store. Look at it! A sanctum of femaleness, of private domestic acts. She wants to blow up so many discussions we bury about the capaciousness of pregnancy and transition, all the lines that get blurred and crossed, the queerness here. In an earlier chapter, Ames experiences a breakthrough of personal discovery in Glamour Boutique, a crossdresser fetish shop; the baby store serves as a funhouse reflection, all the drag that comes with procreation.

Nelson dives deep into the way these queer realities of the body, including eroticism, inhere to the process of motherhood, only to be met with stigma and shame. She discusses the sharp privacy of breastfeeding itself, with its reminders of the animal body. It’s another area where a whole new language opens up once you’re past the shroud—colostrum, letdown, hindmilk. Visual records of the act are limited to pumping manuals and, she notes parenthetically, porn. Nelson turns over an image from an art show, where a woman pumps while staring into the camera; she marvels at the way that radical intimacy in queer media often sounds in genres of danger, suffering, abjection, but here the queerness is nourishment from the body. Nelson pushes not only against mainstream discomfort but queer culture too—where queerness is so often idealized in the masculine, against anything too close to the female animal, she seeks a vision of queerness unbound and capacious enough to hold this too.

Reese picks up this precise conversation, staking a claim to the same mess and complexity for our stigmatized femme bodies. There is reciprocity for Katrina as well; this opening is what she needs too. She confesses how, without Reese, she would run from the store screaming. For Katrina, with all her discomfiture around the normative glowing mother story, for whom conformity is alienating, this queer liberation that Reese seems to promise looks something like a life she can live.

One of the first changes a trans girl notices is soreness in her chest. Long before breasts grow in earnest, nipples and glands reconfigure, reading instruction and transforming. This often includes, briefly, a few drops of milk. During pregnancy, though I decided against the induction protocol, the milk returned. Always two drops, just two. Whatever the explanation, it arrived and remained well through his first year, until he was weaned. In that time it was a constant reminder of the proximity of our bodies, the blurring, and the distance that remains.

As a trans woman, this notion cuts deep. Our bodies have always been figured as toxic.

Nelson turns over another idea called the toxic maternal, literally the poison in our milk. Toxins are everywhere these days, so that the question is never whether there is poison, but its degree, whether it is safe. As a trans woman, this notion cuts deep, part metaphor, part practicality. Our bodies have always been figured as toxic, an assumption that has founded laws to keep us from having children, or courts taking our children away. Gatekeepers once asserted that to protect children from transition, “young children are better told that their parents are divorcing and that Daddy will be living far away and probably unable to see them.” This language is resurgent in contemporary hate campaigns, where talk of “safeguarding” and “grooming” of children loom large. It’s a core story that society hands us about what this all means.

This sense of toxic maternal was close in mind as I decided early to forgo breastfeeding protocols. I told myself it was practical, a lack of stories proving safety. I read about trans women who did, but the stories didn’t cover nettlesome specifics, like the safety of testosterone blocker medication in milk. And then it struck me that I had been looking too narrowly, seeking only trans stories. My hormone blockers were, like most trans medicine, prescribed mostly to cis women to treat various conditions. I was not asking a trans question at all, but a woman question. Still, when I brought this to our OBGYN, she was leery. I folded quickly, shut the door and stayed on course, accepting that this body just isn’t safe enough.

When our son was 18 months old, I read Reese’s certainty, and doubt crept in again. I dig deeper. Either science had caught up since then, or I simply chose not to see it. But then it was never truly a science question. It was about little cooler bags of pumped milk handed to daycare staff. It was about a shirt lifted in public, a baby clambering for a chest as people pretend not to look, but look. It was about a story that was no longer just mine, but my son’s first and foremost. Against this, Reese’s certainty is bittersweet. I think of girls who come after who can read themselves into that confidence, how the opened conversation creates more narrative possibility for them, for their full complexity, for queerness and nourishment, for things that will no longer be too much to ask.

In imagining space for her own queer family, Reese recalls a trans man in Chicago she’d met who, along with his husband and a lesbian couple, started a large combined family. They renovated an old Victorian house by the lakeshore, carving two living spaces separated by an open staircase. The cis husband provided genetic material, both women conceived, and all four raised their kids together as equal parents. By the time that the kids realized most people only have two parents, they viewed their peers with sadness for their lack.

I think of a small hand-made quilt, perfect for a baby bed. It was gorgeous, intricate, and so we were stunned to learn that it was the first our trans man friend had ever stitched. I think of a crocheted unicorn doll, white with a mane of rainbow yarn, that a lesbian friend’s mother made for the occasion. From our cishet friends we receive hand-me-down boxes of utility gear, all the practical sundry needed to keep a baby alive, fed, and rash-free. But the gifts from queer community, queer family, were something else entirely.

We expected a pulling-back, a separation, as we began a process often seen as anathema to queerness. And yet, as the baby became imminent, I was astonished by the excitement of so many in my queer circles, a palpable difference from the nods of cishet friends. There was triumph in it, an investment that transcended the usual respectful distance, as if this rare things wasn’t just for my wife and me, but for all of us—a deeper understanding of what community really means.

In his first few months, we performed a special kind of assessment. Friends dropped by to hold him, and we noted who had that spark, who took most readily to that connection. Our vision for all of this, building a world around this tiny human, relied on a circle of adults, particularly our queer friends. We simply couldn’t envision doing this alone. Our queer circles skew trans masc, and with our femme selves already established we had a special interest in finding trans uncles and godthems to balance and expand the tones of in his early life.

We spun a story to support us in this, filling the missing pieces, our community there to provide all kinds of faces and experiences to fill his world. And then, March 2020, we were reminded how little control we really had. He was 7 months old when the pandemic hit. When lockdown began, he couldn’t even crawl yet; by the time that we saw a light at the end, more than a year later, he ran down forest trails, read books, did downward dogs, watered my garden from a bubbling hose. For all our attempt to write it differently, we were all that he had, and we needed to be enough.

Ames, turning over his anxiety about parenthood, remarks how a baby sees through you. Parenthood itself is not scary to him. What’s frightening is a role he could not fit: the role of father. His instinct is to seek a community that could sustain him—specifically the fellowship of trans women, people who see him as he truly is, as the new being’s needs take hold. For Ames, much of the ease of detransition came from how little is asked of a middle class white man, how easily he skates by. This baby’s need tears that all down. It will know him, and he cannot have this baby know him as he is.

Ordinary devotion is a concept that Nelson considers, from developmental psychologist Donald Winnicott: how a mother’s simple task is to give yourself completely to your infant’s need. To give your body, your mind, your energy, your purpose. It’s interesting to set this beside transition, as Nelson does with Harry. Transition is the fulfillment of personal need. We often say that the best thing you can be for others is yourself, that it’s offensive (and it is) for family to place their sense of need ahead of yours. But entering the parent space specifically, so much doubt arises.

We often say that the best thing you can be for others is yourself. But entering the parent space specifically, so much doubt arises.

Late in the novel, as Reese’s dreams once again seem to crash down, she stands on the shore facing a derelict sanitarium, speaking aloud to the ghosts: I lost my baby. Not a hypothetical baby, but this baby. A baby that could still get to be a baby, but only without her—her abnegation an essential act to bring it into being.

This notion, giving your body for a baby, has a strange spin for the trans mother. Many have denied their personal need, stayed in a body shaped like father, for the sake of their children to be or the children that are; to do otherwise, as the story goes, is selfish. Or we find ourselves at a place where we have finally come into the body we need, only to face the prospect of losing it for the chance to make a child.

Peters has spoken of the comma in the title of Detransition, Baby as a pivot, a razor. I read it and see a line of decisions, all the times on this road where I had to make the choice between the body I needed and that hypothetical child. I see the Medicaid clinic room where I initiated my trans care, my NP and I reading preservation reports we didn’t understand, discovering that something was wrong. I recall that sharp fork: do I take hormones to remake my body the right way, or take other hormones to make it a father. I recall our compromise, assured that future IVF would still work at least. I see my own office, the day after our retrieval seemed to fail because my material had failed, right back at the same fork: would I detransition for the chance to complete this? On one side, I knew I had chosen something essential with transition, remaking a body and self I needed in ways I couldn’t even imagine before I found it. There were other ways to have a child. And yet. There’s that trans reality again, the relationship between proximity and need, how the closer you are to the practical possibility of embodiment, the more present and compelling the need becomes. The truth was, I had already attached to this baby, the one we saw together, the one we were making together. With both sides of the scale heavier than ever, I knew that I would try—a new story, another blank page. And then the phone rings, my wife, with news.

I see a bright morning, a Saturday in late summer of 2020, and our one-year-old son played with my wife in our living room. I looked on through the open bathroom door, preparing for shot day, an event that had now become a grounding ritual, a necessary moment I anticipate all week. I opened the old box of needles, and the last one fell out. I stood for a minute shaking the empty cardboard box, the same one we took wide-eyed at the pharmacy when this all started, the one hundred needles now spent. My son climbed over my wife, reaching under her sweater, insistent, close to weaning but not there yet. Two bodies became three bodies. Bodies changed shape together, in passing and in tandem. I held an empty cardboard box, what was left of the needles that precipitated all of it. It’s hard not to think of Nelson’s Argo conceit, her story to frame their passage through transitions, the ship replaced bit by bit until no part is the same. There are so many valences of story for experiences like this, sometimes a mythic allusion, sometimes a spent case of needles. Laying out supplies, even now, I hear the same cadence.