Books & Culture

The Under-Appreciated Feminism of “The Thomas Crown Affair”

The way the story changed from 1968 to 1999 shows growth for the female lead—but there's still further to go

A story: A wealthy man executes a heist and becomes embroiled in an elaborate game of cat and mouse with the woman investigating him for the crime. As their affair intensifies, she closes in on him—and with her, the law. In the end she must decide between her emotions and her principles, as he makes a final play to save himself.

How you present this story—especially its female lead—depends in part on what you expect of women. What does it mean for a woman to excel in her job, to try to get the best of a man, to weigh her feelings with her duties? Now that we may see another remake of The Thomas Crown Affair—a version starring Michael B. Jordan has reportedly been in development for the last few years—it’s informative to look back at the way its central female role has changed. Catherine Banning, of the 1999 film, was an unsung feminist hero. But what would her role look like in 2019?

The original 1968 Thomas Crown Affair is a man vs. society story, whose central question is: Will the man succeed in gaming the system, or will he get caught? Steve McQueen’s Thomas Crown is an anti-establishment, dark-humored playboy millionaire. He drives the story. Faye Dunaway’s Vicki Anderson is a young, stylish, bold (for her day) bounty hunter—the Hollywood Reporter review called her “aggressively amoral”—but her character is never in the driver’s seat. She’s a romantic foil for Crown. Seduction is her boldest move, but she ultimately weakens and becomes conventional, desiring some emotional truth in their romance. For him the affair is only part of the game—and he plays it expertly, pulling off a second heist, escaping scott free. She is left with nothing—not the man, and not the money she could’ve earned by nabbing him.

Her story is: An ambitious ingenue gets played for a fool by an older, smarter man.

The 1999 remake is a love story, whose central question is: Is it a game, or is it love? Is their love true—and if it is, can it transcend the traps they’ve laid for each other?

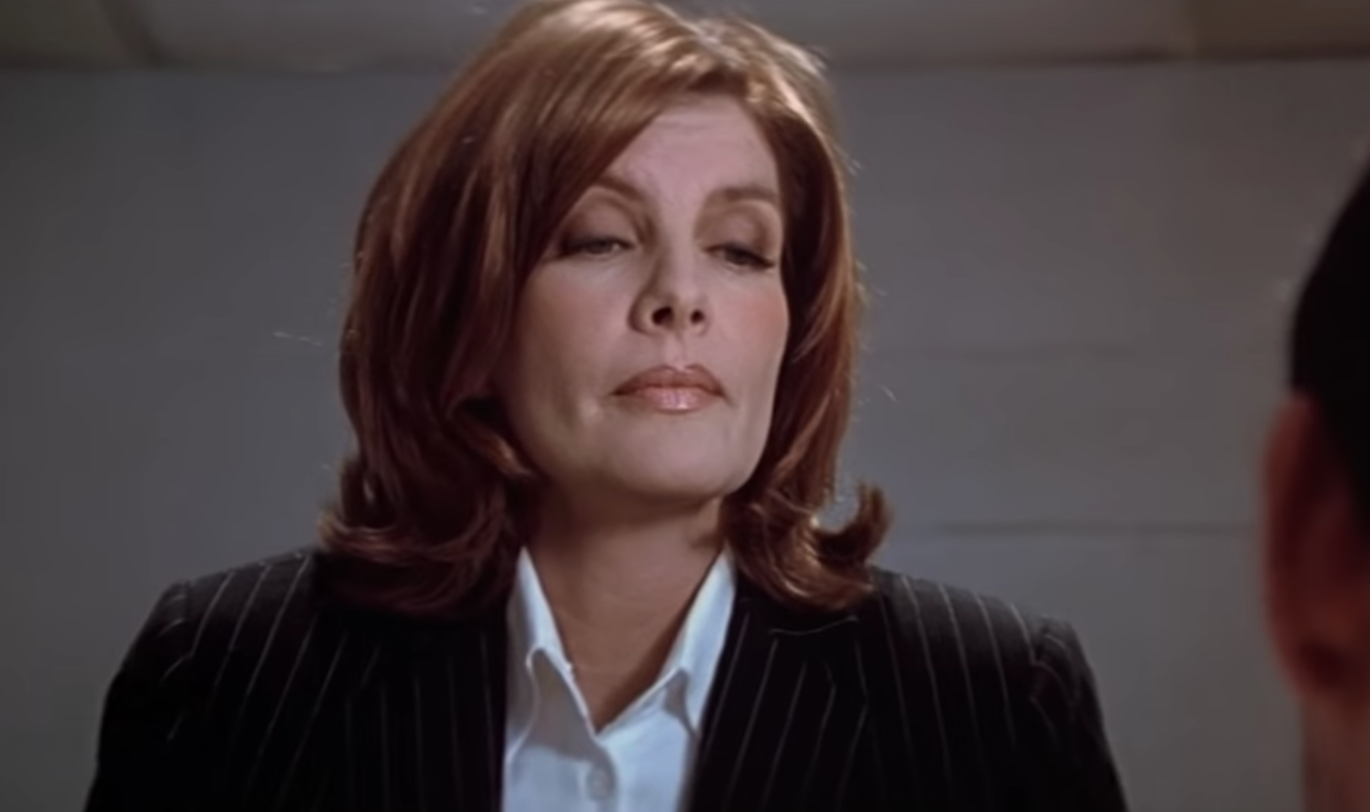

From the moment Rene Russo walks onscreen as Catherine Banning, possessing the kind of swagger that would easily befit James Bond (ironic, as Pierce Brosnan’s Thomas Crown has about as much swagger as a dead fish), it’s clear that she is film’s the driving force and protagonist. She is not only an updated version of Dunaway’s character—she’s also well ahead of her time. She is successful, financially independent, cosmopolitan, and single in her 40s.

(Pause there: a single woman in her forties. Also, she’s childless. Characters like this are rare even today.)

She has the confidence of a man who knows he’s good at his job. She is—in short—an icon of 1990s feminism.

She is Crown’s equal in age and intellect. While she is motivated by the money she stands to earn by returning the stolen goods, she’s clearly doing well for herself already. She lives in an uber-chic wardrobe of Céline and Halston, resides in Monaco, and keeps an apartment in New York. She boasts a prescient taste for green smoothies and a trail of spurned boyfriends across the globe. She has the confidence of a man who knows he’s good at his job. She is—in short—an icon of 1990s feminism.

While Catherine far exceeds her predecessor in capability and complexity, what she and Vicki share is a rules-be-damned approach to the job. Both women scoff the law and use seduction as a means to their end—which, they both insist, is the money—and both are shamed for doing so. In the original, the good-guy police detective grabs Vicki’s arm to scold her for her tactics.

“I do my job,” she says in her defence.

“Your job?” he scoffs. “What the hell kind of a job is that?”

“Alright,” she says. “I’m immoral. So is the world. I’m here for the money, okay?”

In the remake, the police detective is equally righteous, just with a lower voice. When he’s about to slut-shame Catherine for sleeping with Crown, she looks him dead in the eye and asks pointedly, “Are you gonna be a cliché?” But this nod to the tiredness of their gender dynamic does little to free Catherine from it; she still lives in a world mired in debate about what the correct relationship between sexuality and power should be. Should a woman use her sexuality as an instrument of power? Or does doing so only further empower the patriarchy?

In 1968, it was very clearly the latter. Vicki plays right into Crown’s hands with her sexual maneuvers, and he exploits her. Their attraction might be mutual, but we don’t expect him to fall in love with her. Eleven years his junior and less intelligent, Vicki is no match for him. Even with the muscle of the IRS behind her, we never really expect her to win. Although he’d have her believe that she successfully entrapped him, that he was ready to return the money and cut a deal with the law, in reality he is luring her into checkmate. Predictably, the man wins.

But in 1999, things go differently. In this version of the story, Crown falls in love with Catherine—which, given her allure, is easy to believe. The film’s tension stems from our disbelief that she would actually fall in love with him. Her spiritual and financial independence, her strength of intellect, her unwillingness to settle, all suggest an unlikeliness to swoon. But as their luxe affair unfurls—a private jet to the Caribbean, a jaw-dropping diamond necklace—we find ourselves wanting Catherine to be swept off her feet, just like we are. (Spoiler alert: She is, and love wins.)

This is undeniably a victory, a step forward. We are presented with a mature, successful, independent female character, who earns the love of a rich man with her intellect and strength of presence. His courtship is so lavish that we willfully cast aside the question: Does he deserve her? In his therapist’s estimation, he’s a “42-year-old self-involved loner.” He’s cold, and worse—he’s boring. All he’s got going for him is his money. But it’s a lot of money.

So her story is: An intelligent, independent woman over 40 finally finds her wealthy prince. She is swept off her feet. It’s a princess fantasy with a feminist princess. And we don’t care who the prince is—if he’s a felon, if he’s a drab financier.

Catherine’s character is emblematic of the power-suit feminism of the nineties: a woman cut in the mold of men. She’s driven by professional ambition, money, and a desire for dominance. A woman like this was—and still is, in many ways—a revolutionary thing to put on screen. That a desirable, high status man is attracted to her strength, rather than threatened by it, is revolutionary. But Catherine’s story, on the other hand, reflects the boundaries of the feminist imagination at the time.

Nineties feminism triangulates Catherine’s character, fencing her in with three distinct limitations:

- That using female sexuality as an instrument of power is wrong.

- That in moral terms, love > career.

- That every woman wants to be swept off her feet by a rich man.

In the 20 years since the film was made, feminism has evolved enough to open up the first two boundaries. Today, we could imagine a story in which Catherine seduces Crown, nails him for the crime, and rides off into the sunset with her $5 million fee (adjusted for inflation)—and we’d be happy about it. But for that kind of story to work, Crown can’t be desirable. If he’s desirable, we will still brush up against the third limitation—that construct that is still deeply ingrained in our society: the princess fantasy. The fantasy that says that every woman—no matter how financially independent she is—wants to be coupled off to a wealthy prince, even if the life she has made for herself is undoubtedly more interesting than the life she’d have as his princess.

Today, we could imagine a story in which Catherine seduces Crown, nails him for the crime, and rides off into the sunset with her $5 million fee (adjusted for inflation).

Even if we updated Catherine’s character to have more dimension, to have a more emotionally rich backstory, or perhaps to be a woman of color—if we put a handsome and wealthy man in front of her, our expectation will still be that she will want him, that he becomes the prize. To reimagine this story in the context of contemporary feminism, two things would have to happen. One, the financial gap between Catherine and Crown has to be narrowed, so that the affair is motivated by more than money. Two, we have to have a better man for Catherine to fall in love with. If Crown’s character isn’t allowed to hide behind a mask of wealth, who is he? For Catherine to shine as an icon of modern feminism, she needs a feminist man to be her romantic foil.