Lit Mags

Our Relationship is Doomed in Every Universe

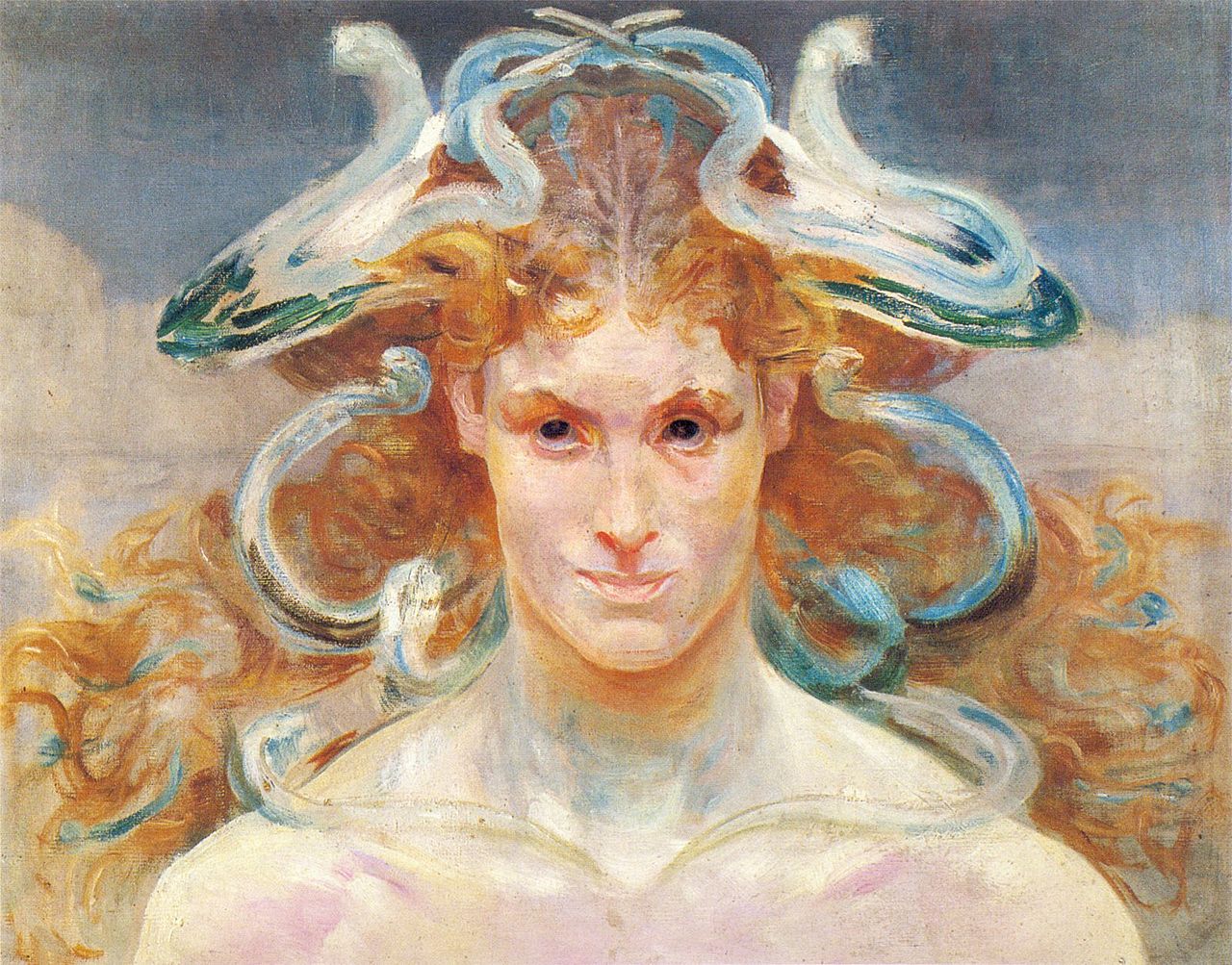

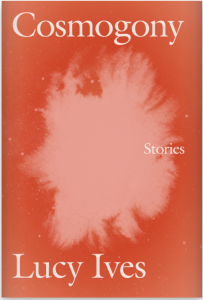

"The Volunteer" from COSMOGONY by Lucy Ives, recommended by Tracy O'Neill

Introduction by Tracy O'Neill

Generally, it seems unfair that the effect of finishing a story should be the impulse to immediately re-read it. There are others to read. Entire Libraries of Babel, if you will. But when a story assumes either the plot of a woman running in a circle, or the plot of what did not happen still not-happening, or the plot of a mind in a future rethinking of the past—and Lucy Ives’s “The Volunteer” manages all three with heady, riddling tenderness—it is only right.

Generally, it seems unfair that the effect of finishing a story should be the impulse to immediately re-read it. There are others to read. Entire Libraries of Babel, if you will. But when a story assumes either the plot of a woman running in a circle, or the plot of what did not happen still not-happening, or the plot of a mind in a future rethinking of the past—and Lucy Ives’s “The Volunteer” manages all three with heady, riddling tenderness—it is only right.

“The Volunteer” announces its postmodern affinities from the get, beginning with the narrator’s musing on parallel universes, after she has just gone on a run past a house once shared with a lover. This lap occasions a recollection of meeting the man she once loved, of how early on he recounted a previous failed relationship with a woman who, in his understanding, was too injured to form attachments. The narrator knows now what neither of them did then: that account had been an admonition.

Whether or not she and the man might have surmised their relationship was doomed from that moment on, much of the story turns not on scenes of pointed love (either falling in, or out) but a conversation on the philosophical problem of the time traveler’s dilemma. Throughout these memories, the narrator remains relatively calm, clear-eyed until in one moving moment, she becomes insistent, exclaiming that she’s not done talking about what he dismisses as “brain in the vat” stuff. Time travel, multiple worlds—these ideas matter to her, matter in the same way that it matters whether someone bothers to make sense of intimacy, or walks away from it as though it never happened, or for a moment permits a turn to failed love’s tense: the past perfect, the what if we had, what if I had.

Like Jorge Luis Borges—who the author nods to in a perfectly pitched characterization of the former lover as a guy who “idolized Robert Frost, not Borges”—Ives takes an interest in the story as a puzzle. Though warned how “The Volunteer” ends, in each subsequent reading, I am struck by Ives’s sleight and grace as the narrator closes her loop of memory, a woman in the process of becoming as she unbecomes who she was. Time traveling, she now, mercifully, knows, offers its own forgiveness.

– Tracy O’Neill

Author of Quotients

Our Relationship is Doomed in Every Universe

Lucy Ives

Share article

“The Volunteer” by Lucy Ives

Some people employ a theory of parallel universes to explain time travel. Maybe I am one of them.

If you ask me, a science simpleton, what I mean by “parallel universe,” my answer may vary depending on the day, but usually I mean something like, a hypothetical plane of reality, coexisting with, yet distinct from, our own. The main difficulty here is that I do not know what I mean when I call something “hypothetical.” Maybe I mean that that hypothetical plane of existence (a.k.a. parallel universe) is elsewhere and unseen, yet actual. Maybe I mean that that plane is something I want to think about right now and sort of cherish, not a combo of time and space where I plan to attempt to exist but rather a pattern I have not yet perceived. It’s not, actually, actual. It’s a thought I’m mentally cuddling.

I’m not sure that I believe in time travel, strictly speaking: certainly, not into the past. I don’t think “I” can go back to the Middle Ages and wander the reeking, pissed-upon hallways of a poorly illuminated castle. I wouldn’t want to do this, anyhow. People seem to forget how common murder used to be.

What I do believe in are coincidence and symmetry, even as I believe in movement (travel!) into the future. Events have a tendency to repeat, and often we can’t tell that they are repetitions, even when they are.

Take for example: me. It is morning and I have gone for a run. I haven’t gone back in time. I mean, I am running in a circle, so I will return to the original point in space from which I departed eventually, but meanwhile time will flow forward, onward, on, rippling along with the space I’ll cover, and soon I’ll be back at my hotel, and then I’ll be showered, staring confusedly at my naked self in a steamed-up mirror, and, then, eventually dressed and ready to depart. And there will be nothing unusual about my day. I won’t get “back” to anywhere.

I’ll only keep on going. I’ll move ahead, out of the present, even as the mirror displays to me an image of myself as I was a fraction of a second before the instant when I looked.

This is my general experience. I am this organism that is knit in space and time.

The one thing I have not told you yet, and that I have to suppose you therefore do not know, is that the place where I am in this instance is a small city in America where, many years ago, I used to live. Thus, I’m currently engaged in more than one type of spiral.

Let’s call this city “Iowatown” (not its real name).

Now imagine me running.

I am not a thin person, but I am strong and have biggish calves that carry me quickly. I’m bounding through all the new construction, listening to a song about female aggression. The singer is going to date your boyfriend. The singer can’t help it. Your boyfriend is extremely persistent and the singer is casual about her entanglements. You, addressee of this song, don’t stand a chance. I listen, running and panting, directing myself along my one-point-five-mile loop, and I identify with the singer, not with the person to whom the song is allegedly addressed. I believe myself to have the correct disposition toward these lyrics.

I’m far enough into town now, into the residential part of “Iowatown,” and I do regret my inability to drop the quotes, that I seem not merely to be moving in a standard fashion into space. This is the tricky part of my experience that I was attempting to intimate. I feel, in that cliché, like I am going back in time.

But I’m not, I think to myself, I’m not, I’m not, although here I am, planted in front of the old house, a warren of slapdash rentals, where we used to spend all our time together, and where your downstairs neighbor was a grinning monomaniac who claimed he’d been a professional boxer in his youth and told you about how he had gotten a certain well-known female memoirist “hooked on heroin” when she had come through town in the late 1990s. Maybe you said he said “horse.” I can’t remember. He was proud of it, though. “That bitch was wild for it,” you said he said. You claimed he made you call him “Greenie.” “Greenie” was not his actual name and bore no resemblance to the two suspiciously common Anglo-Saxon monikers taped to his mailbox. John Smith called you “Stud,” presumably because of sounds we made in your attic efficiency. “Hey, Stud!” John Smith cried after you, from out his open window. “I’m watching you, Stud!” he yelled. Sometimes I was there. John Smith had a high-pitched voice and was an otherwise nondescript middle-aged man who was never without a hooded sweatshirt, even in summer.

The house is still white, bluish. It still has that porch in front with the pattern of circles punched in the wood below the railing. There is still the elaborate fire escape, the one that touched your bathroom window. Someone else must live up there now. Someone may, even at this moment, be standing on that same police-blue wall-to-wall carpeting, gazing out the window at a pausing jogger.

Meanwhile, the prehistoric sun beats down upon the little sidewalk where I stand in my running attire. The sun warms me, although I feel extremely far from my skin. I may have begun running inside a narrative, but now that I am here, here before the residence where you used to live and where we lived together, I see that this is not merely my destination. It is a net or a kind of a mirage, and it has caught me.

And when we met, if you will recall, we were both walking on the street not far from here. I felt, that day, that I was being watched, as if from some point in the sky, a pinprick. You, meanwhile, didn’t look, not at first. You were engrossed in a copy of Kurt Cobain’s diary, which you had borrowed from the university’s library, and which I thought was an ingenious thing for a graduate student to be reading, although I did not tell you so at the time and, then, never told you later. Something started in that moment that was different from all other things that had begun in my life thus far. That tiny piercing in the heavens stayed there, unblinking. You lifted your hand from the page you were reading; eyes previously cast down went up. You seemed to hear a voice: you were being notified. You recognized me from somewhere, from some hallway or classroom. You beckoned. There was no pause in this, no flinch. You were not shy. You seemed to have practiced for this encounter for months. And when, in the subsequent one point five decades, I thought of it and you, I sometimes wondered if everything had indeed been rehearsed, if not predetermined.

I approached you willingly and we walked and saw a miraculous sight: a tree filled with small yellow birds, in the branches of which there was also an abandoned cell phone charger, the kind you plug into the cylindrical cigarette-lighter cavity in a car. The charger had a long, coiled cord, of the sort you never see these days. It was elaborately tangled. And I never saw any of those small yellow birds in Iowa ever again. Yet, they were there on this day. They twittered piteously, as if the air was being squeezed out of them by unseen human hands, and I remember the sound as deafening, but that may only have been an internal tectonic shift, the squealing of heavy stone against heavy stone as forgotten hope was released from the spiritual prison I still did not realize I had inherited from certain of my ancestors.

We would retrace this route many times. Nothing about this was remarkable, except that it began. It felt to me, if not like the will of god or the CIA, then like a glitch. We had gained access to a parallel timeline. I had stepped out of my previous path, whatever that had been.

You told me a story early on, and I sometimes think it could have helped, if only I’d understood you. You were warning me, but neither of us knew how to decode your narrative, which appeared, erroneously, to be mostly a story about you. You told me that when you were in college you had fallen in love with an older woman.

“How much older?” I asked. I didn’t know you well at this time.

“She was five years older,” you said. You said it would have been less than that if things had, if I could understand, gone as normal.

“Normal, how?”

You explained that this woman, whose name was hazily tattooed, stick and poke, into the flesh of your upper right arm, had several years before you met her been hitchhiking with her then-boyfriend in the desert in New Mexico.

“What was she doing there?”

“They were just there. Camping or something. Like they’d try to do crazy things for free.” And you said that they had gotten a ride one afternoon that was going to take them pretty far back across the country, something insane, like all the way to Chicago. “You have to watch your luck,” you told me.

I must have nodded. We were up in your apartment and maybe it was a month after we’d first met.

You said that they were driving with the people who picked them up in a Jeep and this woman, whom you later loved, fell asleep in the backseat with her boyfriend. They were sleeping with their heads on each other, you said. I never knew how you would have known this detail or why it was important. It had nothing to do with what happened next, either in the story or, I don’t think, in our lives. But I did have the thought that this woman you loved was amazingly lucky and liberated. She could hitchhike and she could fall asleep.

She had a boyfriend who did these things with her. Her head rested on him. She would be carried back across the country, essentially for free, because she willed it.

“Later,” you said, “they woke up and the car was going really fast. They turned around and looked behind them and they could see lights.”

I wanted to know how fast.

“They were going over a hundred miles an hour.”

I didn’t ask you why. I let you explain about the Jeep rolling. I had never been in a serious car accident, but somehow I could imagine that period of time, how images yawn before the passengers, outside of any temporality. And you said that she had described it to you, solemnly; how the only way to survive is to go limp. How she knew about that somehow. How she credited her survival to this particular information gleaned, I guessed, from film.

The couple who had picked them up had drugs in the car. Not an insignificant amount. They were inexperienced professionals, apparently. Rather than be pulled over, they’d decided to make a run for it.

No one survived except for the woman you loved. And she was in the hospital for a long time and it was several years before she could return to school. She moved back to Iowa to be close to her parents. This was where she met you. You said you were pretty sure she understood how you felt about her, but it was like something in her was bent and couldn’t catch. Not that she couldn’t form new memories, but that people were, at some deep level, nothing more than animate sacks to her. And there was a whole year after the crash that she could not remember, a substantial portion of which she had spent in a medically induced coma.

When you told your father you wanted to marry her, he threatened to disown you. You never told me if it was because of the accident or something else. You said you locked yourself into the non-working sauna at your parents’ home outside Chicago for a full day, on Christmas no less, but they wouldn’t budge.

Later, when she eloped to Ecuador, you were glad, you said. You still despised your father, but you recognized that he had saved you from certain humiliation. It was unclear what role your mother may have played.

You said that none of it mattered and how you’d been stupid. You hadn’t known anything. You said that sleeping around was part of her condition. You claimed that this was common when it came to traumatic brain injury.

“I’m sorry,” I told you.

“Don’t be.” You were embracing me. You were saying that your younger self was very, very dumb.

One might have thought that because I had never been in love before I would not have had an analogous story, but I was a reader and because of this I was seldom without something to say, at least when it came to plot.

I told you then that I thought a lot about going back in time. I had recently learned of Hugh Everett’s so-called many worlds interpretation, broached in his 1957 dissertation and entirely disbelieved until the 1970s. I was probably mostly misunderstanding, but I had become obsessed with the idea that by regressing, temporally speaking, one travels down the limb of a metaphorical decision tree. One moves in the opposite direction to time’s arrow and therefore against the grain of the increasing entropy that pulses inexorably into the future of our universe, according to the second law of thermodynamics. Even as I was saying this to you, I said, given quantum events, there were worlds coming into being in which I changed the subject, or a bat flew in through the unscreened window, or you interrupted me to insist that we should head to the bar.

“Wait, what time is it?” you wanted to know.

If we could go back, I said, to the first word of my first sentence, these worlds would not exist.

You were digging around your desk, in search of the cordless phone.

“I’m not done!” I called from the kitchen.

“Hey, man,” you were telling somebody. You covered the receiver and asked if I wanted to join.

“I want,” I said, “to talk about the time traveler’s dilemma.”

You said more things, re-buried the device.

“At your service,” you told me, reappearing. “What’s this about brains in vats?”

This was before you knew, I think, that you hated ambiguity. You idolized Robert Frost, not Borges. Where paths diverged, you’d squeeze out a token tear for the road not taken and move amiably on. What wasn’t or didn’t or couldn’t, for you, simply disappeared. You liked to pare things down, is what I’m saying. I do remember all your folding knives, inherited from your grandfather, an engineer, or purchased secondhand—how you kept them in a yogurt container as if they were a kind of art supply.

“The time traveler’s dilemma. Because once you go, you can’t go back.”

“Haha,” you said. “Back to the future!”

“Well, except you can,” I clarified. “I think. Sort of.” And I started recounting the plot of an old sci-fi story that had really impressed me, embellishing as I went:

Once upon a time in the late twenty-first century there is a research corporation that has a bunch of agents who are able to make use of time-travel vehicles to go into the past. They’ve noticed the tree of entropy; in fact, it’s a major reason for their interest in the past at all. Since quantum events in the present always double the world, and since what happens is composed of many quantum events, everything that can possibly happen is happening in some world unconnected to ours. We live in one world, but there are many others. The alternate worlds are full of interesting things: the predictable victorious Nazis, among other historical mutations; speaking cats. But if you go back in time, you follow, as I was saying, what amounts to a coalescing, unifying stem. You slide back away from those moments of doubling.

“Sounds complicated,” you said.

“Not really,” I assured you.

For an obvious problem arises when you want to move forward again: How will you be able to recognize the world-strand you came from, particularly when it closely resembles a number of others?

Here I grew enthusiastic, leaning across the table. I felt sure you had to get on board with this: The time-traveling agents solve this problem by leaving a signal on in the garage where their time machines are kept. The signal has a specific frequency, so they know in which strand to dock. The signal matches, of course, in a range of original-esque worlds, worlds with an identical time-machine garage, with identical devices to make a signal, with near-identical events around the programming of the signal. They’re all similar enough to one another that who really cares if things are a little off. This is still late capitalism, after all, and risk accrues to the freelancer.

But speaking of risk, there’s another problem. (This was my grand turn and I really tried to bring it home.) The research co. has lost a ship. There’s nothing but charred remains outside one dock. HR, ever thrifty and enterprising, offers a reward and finds a volunteer to loiter in local time lines, keeping an eye out. The volunteer follows past versions of the dead man and discovers: This pilot, anxious over the maintenance of his precious personal identity, tried so hard to return to the exact thread and exact moment he had left that he fatefully overstepped. He met himself on the way out of the garage in a catastrophic accident! I guess future fuel is highly combustible.

But this is only the first in a series of accidents, deaths, and disturbances. The fear of losing one’s original narrative proves contagious. It troubles some, while others succumb to many-worldly nihilism. Some pilots elect to return to a world that precedes their departure by several hours. They park their time vehicle behind a bush, stalk themselves, commit murder. Meanwhile, others, less confident types, live in constant fear of self-slaughter and destroy their time machines or preemptively end their own lives. Still others don’t return. And others still, recognizing that it doesn’t matter, for in a parallel world they will decide differently, walk out of windows or—

You interrupted. “I don’t get it,” you said. “What’s the dilemma?”

“Don’t you see,” I told you, “how time has changed?”

“Not really.” You were scrubbing your face with your hands, as if to ward off sleep.

And so I did not say that it’s not being out of time that’s weird for the time traveler but the retreating uniqueness of the self of the time traveler, the rise of a nonsensical style of interpersonal competition. That in this universe the time traveler’s dilemma is whether to kill themselves or die, although in truth the two options are hardly very different.

But here came you again, brushing aside the web of slumber and characteristically in search of a protagonist: “What happens to the volunteer?”

“I don’t know,” I said. I felt defeated. “They’re just a plot device.” In this I was wrong, but it wasn’t until much later that I knew why.

Maybe now you informed me cutely how I made you nervous. I can’t recall. Maybe you laughed and squeezed the top of my knee; maybe my knee jumped. Perhaps you frowned and licked me.

At night you would jerk around like a windsock and you talked to yourself, nattering on about presences and tasks. Sometimes you got up and paced, wailing incoherently. I’d find you on the floor in the bathroom and you wouldn’t know where you were or how you’d got there.

On my run, I could not have been stopped for more than ten seconds, fifteen at most. On I pounded, and the white house and its spectral signal fell away.

I used to like to think, what if I could go back in time, back to that year and day and meet us on the narrow side walk in the grass, perhaps at the very moment when you’re showing me the page on which Kurt Cobain begins waxing melancholic about his alter ego, “Kurd.” What if old me snatches the book out of your hands and starts beating you savagely about the head until you are either incapacitated or fully dead? Or, what if old me walks up to young me and uses impeccable logic, along with what I’ve since learned about human psychology plus epigenetics, in order to convince young me that I can do better? I’ve thought about transforming myself into a sort of speaking particle and somehow journeying into my own naïve mind, to beg myself to reconsider. I’ve also thought about the time traveler’s dilemma and the fact that I am living. And therefore wasn’t there.