Interviews

The Weird World of Selena Chambers

Talking hot-weather Gothic, getting paid for your writing, and finding a home in the sprawling world of Weird Fiction

I first met Selena Chambers at the 2015 World Horror Convention in Atlanta. Since Chambers was “bar-conning” it that year — the convention-circuit term for hanging out at bars in and around the convention center and/or hotel to drink with people you know instead of attending the panels — we hadn’t officially met before then. We talked for a total of maybe 10 minutes. Chambers, however, would leave an impression: graceful, solicitous, intensely perceptive and interested, like me, in a narrow subset — 19th century American occult arcana. That night, I forgot to pay my bar-tab and had my cabdriver return to the bar; when I entered and threw a few bucks on the table, Chambers applauded and said, “Nicely played, sir!” That moment would prove providential as Chambers and I have returned many times, though never in person, to talk about fiction, carrying on an email correspondence right into the present day.

So it was with no minor jolt of elation that I began reading Chambers’ debut collection, Calls for Submission, which rolls out a wild and eclectic array. Perhaps needless to say, it did not disappoint, given what I knew of Chambers; it’s a creepy-sad, smart and courageous collection that stimulates the intellect while inexorably pulling and pulling the heartstrings. In “The Sehrazatin Diyoramasi Tour,” a 19th century Turkish automaton shows a crowd of European tourists a series of uncomfortable and, progressively horrifying truths; in “The Last Session,” a tender-hearted adolescent caring for her ailing mother makes expedient and unorthodox use of hypnotic techniques; and in “The Neurastheniac” (nominated for a 2016 World Fantasy Award), the spiritual unraveling and death of an Emily Dickinson-by-way-of-Diamanda-Galas-esque poet disperses before the reader in a flurry of journal entries and poetic fragments. In June, Chambers and I did the emailing thing in order to discuss reclaiming literary territory, “the female glance,” being a hot-weather Goth, Florida weirdness, and the non-intersectionality of literary circles.

Van Young: Individually, the stories in this collection are eclectic, but marvelously self-contained. Eclectic, in that they often hop among genres (dark fantasy, cosmic horror, steampunk vaudeville, etc.), and many of them are often riffs on historical arcana, or other stories altogether; for example, “The Last Session,” probably my favorite story in the book, is an after-school special screamo-punk riff on Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar,” while “The Şehrazatın Diyoraması Tour” seems to take on Ambrose Bierce’s “Moxon’s Master” and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, as well as other tales of Victorian automata. Self-contained, though, in that they never fall prey to meta-contextual preciousness, but stand on their own as both literary artifacts and accomplished short stories. The sum effect of the stories is truly arresting — like being whisked through a curio-shop of the last few centuries’ most telling fantastical preoccupations. In keeping with the riff-based quality of many of these stories, were there any other collections as a whole that served as literary templates in how you constructed your own?

Chambers: That’s tough because I really do love the short form, and love reading it, but the truth is I had no designs on having a collection until around 2015, after the majority of the stories were written. And when I did start thinking about it, it was more of a personal aesthetic-check-in to see what I’d been doing for the last decade. Because I’d solely written for themes and anthologies, I was really worried my body of work was too eclectic, and that I had wasted ten years ignoring my own aesthetic interests for the market. I was pleased to find that there was, for the most part, a core mission I was somewhat aware of, but I was unsure it was being fully executed.

So that’s what went into the collection as a whole, but as far as its parts go, there are a lot of influences. Each tale in Calls for Submission does have a better counterpart that influenced it. For example, there’s some Wodehouse and Fitzgerald in “The Venus of Great Neck,” but that story is most in-debt to Mèrimée. “The Şehrazatın Diyoraması Tour” was definitely influenced by Mary Shelley, but also by Nick Mamatas’s “Arbeitskraft,” which is a Steampunk novelette about Marx and Engels. It showed me how to subvert things I disliked about that genre while celebrating those things I loved.

Van Young: I see that element of eclecticism-as-subversion there for sure. As a whole, the collection reminded me a lot of Borges’ Universal History of Iniquity, where Borges takes these unrelated myths about larger-than-life historical figures and narratively & culturally re-contextualizes them, often with an absurd twist. Indeed, maybe it’s that quality of re-contextualization and recombination that I find so resonant between your work & Borges’. Yet now I should ask, since you mention it, what have you been up to for the last decade? What’s your core mission?

Chambers: Thank you! Borges has been one of the great “re-mixers” I’ve been interested in over the years, and I definitely took a few notes in regards to re-contextualizing history for excavating new stories out of the old (or, I guess even, the untold).

The last decade? Oof, can I even remember? When I graduated college in 2004, I forgot to apply to grad school and started writing for money.

I know. Hilarious, right? This was before everything was completely gutted though. Even so, it was a hap-dash CV: jewelry copywriting, student papers, glossy pop-feminist essays for pop-up Internet women’s magazines, and Rum Diary times at a weekly newspaper in South Florida. What I wanted to write was fiction, but I didn’t know what to write about, so I literally wrote about everything else that paid.

Eventually, this philosophy lead me to Genre via non-fiction thanks to the Poe bicentennial. Poe is a major influence, and so it was a natural fit. It was the missing ingredient to figuring out what I wanted to write, fiction-wise. Through Genre, I became aware of Steampunk, Interstitial, and Weird, as well as the overall enthusiasm for remixing and mashing literary works and historical figures in a way that I had been toying with in my early stories. So, I started experimenting with that more and…here we are.

As for the core mission…back to Poe for a minute. I got into him at a really young age and he was a gateway to many things for me, including Baudelaire, French Symbolism, Modernism, Dada, and Surrealism. (This is how I found Borges, btw!). I was very much bespelled by Poe’s Poetic Principle and interest in ordering the Universe (Eureka), and as you can imagine, that imbued me with a Goth girl sensibility and unhealthy interest in death and metaphysics that I aped until around my junior year.

That’s when I really got into Modernism, Dada, and Surrealism, and fell in love with Mina Loy. She was interested in creating and exploring the female space beyond Wollstonecraft and Woolf. Breaking out of a gilded cage to be in a room of one’s own was not enough for Loy. She wanted to see worlds, countries, cities, or, at the very least, a Library for women’s experiences.

In her essay, “The Library of the Sphinx,” she summarizes my core mission in one line: “Your literature — let us examine it your literature — It was written by the men — .” I am trying to look at what’s been written by the men (Lovecraft, Poe, Verne, Robert Chambers, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, William Burroughs, etc.) and exploring and clearing the spaces for lost (mostly feminine) voices within it. And because I am still that little Goth girl at heart, most of this space is within the realm of loss, illness, and submission.

Van Young: As a fellow hot-weather Goth, I salute you! I love what you say here about “exploring and clearing the spaces for lost (mostly feminine) voices within” male-dominated literary traditions. You know, I read an essay recently in response to Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale (“The Radical Feminist Aesthetic of The Handmaid’s Tale by Anne Helen Peterson) that made a case for the show — and other more meditative, female-centered narratives like it — as a purveyor of what the writer calls “the female glance,” which functions as a complement rather than an opposite to the “male gaze” put forth in Laura Mulvey’s 1975 essay. “Unlike the steady, obsessive gaze,” Peterson writes, “the glance is sprawling, nimble: not easily distracted so much as a constantly vigilant. It scans, it flits, it spins — or, alternately, it observes, with patient detail, the moments of a woman’s world that often go unnoticed.” I often found myself conscious of such a “glance” in Calls for Submission. Is it safe to say, then, your overall project of “exploring and clearing spaces” in your stories cuts all the way down to the images you — often cinematically — create? The phenomenological way your primarily female characters navigate the fictional worlds, and meta-fictional literary spaces that surround them?

Chambers: Ugh, yes. Hot-weather Goth is a whole drippy, wilting identity we must hash out! Is Swamp Goth a thing?

I was very much concerned with trying to do something like that, to shift the gaze. Before I really realized what I was doing, I started exploring that shift in “Of Parallel and Parcel,” which has Virginia Poe confessing her life in her willful terms in a way that defies Poe’s poetic principle. And I think I really started realizing what I was doing with the gaze when I wrote “Descartar,” whose mission was to retell the “La Llorona” myth through the lens of abortion in a way I hadn’t seen discussed back then. The whole notion probably became fully realized, though, in “Remnants of Lost Empire,” where I rejected all of the male-dominated Miskatonic assumptions of who is writing what and conducting what scholarship and why.

Van Young: Moving on to some of the individual protagonists in these stories such as Virginia Poe, as you cite, from “Of Parallel and Parcel,” or the narrator of “The Last Session,” or that of “Dive in Me.” There’s a certain doomed naïveté operating in many of these characters, but one that’s never not allied with a sort of weary wisdom — the knowledge that, indeed, everything will not turn out all right, the characters just don’t know it yet. Also, so many of these characters make terrible decisions and not necessarily on the path to making the right one. On the whole, though, they’re identifiable — likable, even, which is something I feel we sometimes lose sight of in our dash to ally ourselves with “unlikeable” characters. How did you achieve that balance? What are some other tensions you seek to capitalize on in your characterizations?

Chambers: Dang. That’s a tough one. I guess I’ve always been fascinated by the false notion that we have control of our lives. That with a bit of sense and careful planning we can unlock the path to happiness. To an extent that can be true. I don’t believe in predetermined destiny, but no matter how diligently you plan, there are a few forces that can come in and fuck it all up. Government, illness, natural disasters, death, and the influence of other people and/or society. Even when we don’t have these forces interfering with our lives, there is always a risk that what we think is the best decision could turn out to be the worst. So, I am interested in exploring character through that lens.

“There is always a risk that what we think is the best decision could turn out to be the worst.”

I wasn’t sure whether I accomplished that in a balanced way, so that’s great to hear. If there is any kind of secret to how I achieved that balance it has to just be from listening and observing how people talk about their own decision-making. In the South, people will tell you their life story at the drop of a dime, so I have had a lot of opportunities to hear different experiences and perspectives on life choices. It’s usually never cut and dry. I never hear “That was the best or worst decision of my life,” but I do hear “I wish I had known this…” or “I didn’t know better at the time….” So, I try to be true to that and eschew absolutes.

As to other tensions…in “Dive in Me” and “The Last Session” I was very interested in seeing how we change our personalities, or go against our better judgements, based on who we are around. And I hope the dialogue in all the stories at least show how we try to manipulate each other with what is said and unsaid. There is also the traction of the inner mind, which is probably most explored in “The Neurastheniac” and “Remnants of Lost Empire,” and somewhat more playfully in “The Good Shepherdess.” As someone who lives 90% of the time in her head, I am really interested in how you can get to know a character solely through what she wants to divulge. In the case of these stories, it’s through writing — be it journaling, poetry, or through letters.

Van Young: You mention you’re Southern, you live in South, yet I don’t necessarily think of you as a Southern writer. But now that you mention it there’s a certain strain of witty Southern fatalism in your work, as well as an aesthetic I can only describe as grotesque. And yet your work ranges far and wide of any concrete notion of, say, Southern Gothic, or self-consciously regional fiction. As we touched on before, you’re also a self-proclaimed hot-weather Goth! A woman writer who seeks to reclaim territory in a field (weird fiction) and cultural/literary landscape dominated by men. You’re also an intensely literary writer who, so far as I know, identifies more strongly with genre traditions. How has being somewhat of a square peg in a round hole informed your work?

Chambers: It’s funny you mention the Southern Gothic thing. I’ve actually been mulling this over a lot, lately. There are definitely two stories in Calls for Submission that are riffing off of the Southern Gothic tradition, but I’ve always viewed them within a more specific lens that I’ve termed the Florida Gothic. I live in North Florida, and not only do we have your standard trappings of ancient oaks and Spanish moss, but a lot of tropical landscape flourishes as well. We got drunk college students and pompous politicians brawling in the streets, and because of the interstate access there are always a new group of drifters or Chattahoochee discharges passing through. The beach is nearby, but so are the springs and the swamps, and both carry the ancient and silenced within their tides. Indian burial grounds are scattered about, which is always good fodder for scaring kids, and there have been occasional serial killers around, which is better fodder for scaring adults. So, yeah, the general anecdotes, gossip, and conversations around here make for straight weirdness. It’s like Faulkner meets Florida Man, and no matter how innocuous the day starts out, you never know what fresh from Florida hell it’s going to end at.

“It’s like Faulkner meets Florida Man, and no matter how innocuous the day starts out, you never know what fresh from Florida hell it’s going to end at.”

The running gag, I think, in my more Gothic stories, though, is trying to get away with defying death, and there isn’t anything more fatalistic and grotesque than that. And I learned that from Poe, Mary Shelley and the Romantics, Baudelaire and the Symbolists, and later on from the nihilism of Dada and Surrealism. So, I guess my aesthetic development was informed more from European sensibilities (with the exception of Poe, but it was true for him, too) than any true Southern ones. But, even so, you can’t escape where you live.

Those same influences is what I think has lead me to fit into the Weird somewhat, although I don’t necessarily self-proclaim myself that. Which ties into being a square peg. I like writing different kinds of stories and playing with and learning from different styles. I’ve never really viewed sub-genres as publishing labels so much as potential tools to add to the writer’s toolbox. So, for example, my story “The Şehrazatın Diyoraması Tour” isn’t quite Gothic, isn’t quite Steampunk, isn’t quite Transhumanist, because it’s a story that uses elements of all of those subgenres to create a more interesting effect than if it were hardcore this or that and stayed within the rules of one genre. That does make my stuff hard to classify sometimes, and is why the Weird umbrella has been nice. Either way, never feeling like I have to conform to this or that category allows me to play and explore a story more and have fun with it, which is what’s important.

Van Young: I strongly relate to that sense of playfulness in my own work. Being a little bit all over the place not because I’m trying to make some massive statement about genre experimentation, but just because it’s sort of who I am, and what amuses me as a writer. But our genres do, in some ways, define us as writers, at least in terms of who we end up associating with — our communities. When we met at the World Horror Convention in Atlanta in 2015 I was struck by how, including yourself and other writers like Molly Tanzer, Jesse Bullington, Craig Gidney, Anya Martin, and Orrin Grey, etc. there was this whole other spectrum of literary genre fiction out there I’d never experienced, just because I’d been going to AWP, if I went anywhere, and that had totally defined my social space. If genre barriers really are breaking down in the way everyone says they are, why don’t all writers of all genres associate more often? How do we broaden the community?

Chambers: I’m so glad you had that experience at World Horror! It certainly was a special one. I’m really looking forward to checking AWP out next year for the same reason. I know there are other Venn Diagrams out there I want to intersect with, and so I hope I’ll get to have a similar experience there like you had at WHC.

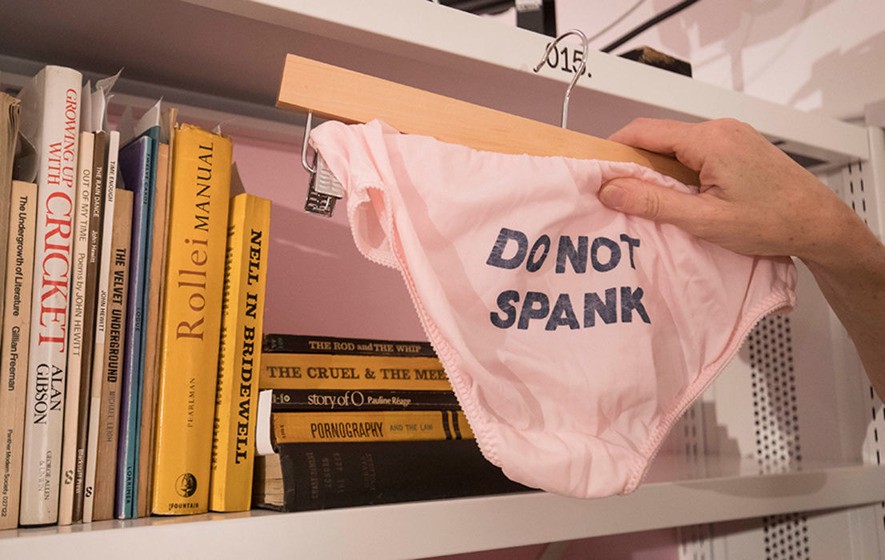

The genre barrier has always astounded me, and from what I can tell, it starts in Academia, and the classist elitism it breeds. Over the years, I’ve been in conversations with several friends who went through various MFA programs, and the consensus is that if anyone rolled in with a horror story they’d be spanked out of the workshop. Ditto sci-fi, fantasy, etc., even though genre barriers are supposedly breaking down.

We also have huge disconnects when we discuss the approaches to our careers. Money isn’t necessarily the end game for me, but as a freelance writer it has to factor into things. That whole notion that the writing is worth something, even if it’s just a few pennies a word, just get blank stares from writers working within academia. If a CV has too many paying gigs, you are seen as too genre (even if you aren’t writing capital G stuff). Which…I don’t understand, because it seems to me if you are going to spend a lot of money and time studying a craft, the expectation is there might be a return in the end? So, the whole “I don’t write for money thing” promotes an interesting pseudo-aristocratic class dynamic that casts Genre basically into the “working classes,” and MFA as “nobles” when they’re actually serfs.

Not that we’re liberated in Genre, either…there are problems on the other side down here in the scum pond. Many problems. But, as far as community ambassadorships go…Genre is more fandom driven than anything else, and as a result, a lot of participants could care less about what’s going on beyond it. And it does take two to tango and all that.

“The whole ‘I don’t write for money thing’ promotes an interesting pseudo-aristocratic class dynamic that casts Genre basically into the ‘working classes,’ and MFA as ‘nobles’ when they’re actually serfs.”

Van Young: What you say about the binary of making money off writing creating a “pseudo-aristocratic class dynamic” is fascinating to me, and kind of right-on. It’s weird, right? You want to make money off your writing because why shouldn’t you, but also it’s become such a martyr’s art-form in some ways, you’re expected not to from the get-go and so when you seek to — actively — it can somehow depreciate the value of your work. I’ve always felt the genre community provides a much healthier template for how writers should be treated and paid by publications and editors in general. But we all have a lot to learn from each other, besides! Who are some writers and works (besides Calls for Submission) you see bridging the gap these days that particularly interest you?

Chambers: It is really weird! I mean, of course, speculative fiction may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but neither are straight-shot family sagas. But it seems like there should be room for all stories! The point of craft, to me, anyway, is you have the skills to write the best kind of story regardless of genre.

So, having said that — yeah, there are tons of writers bridging the gap between speculative fiction and lit fiction. Coming from the lit fic side: Amelia Grey and Karen Russell come to mind. One of my favorite science fiction stories,“Black Box,” is by Jennifer Egan. I just picked up Leyna Krow’s I’m Fine, But You Appear to be Sinking which looks like it’s going to be filled with very memorable tales and weird shenanigans. And I also have on the stack Lidia Yuknavitch’s Book of Joan which is a dystopian, alternate history of Joan of Arc. I haven’t read Sander’s Lincoln in the Bardo, yet, but from what I have heard that would definitely fit into this conversation.

So that’s just a few of those…on the other side, dang, let’s see. Molly Tanzer has a new novel coming out this November from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Creatures of Will and Temper. It remixes The Picture of Dorian Gray and diabolism to explore the competitive and unconditional relationship of sisters, and I think is really going to speak to a lot of people with sibling feels (and Decadent feels!). Paul Tremblay’s last two novels have really crossed the bridge and opened port to readers who might not otherwise read horror. I think he was able to show just how much deeper into the human condition it can take us, especially with A Head Full of Ghosts. On the weird historical fiction front, Jesse Bullington’s The Folly of the World is a beautiful time-capsule of thieves and waifs struggling with some spookiness in the wake of the Saint Elizabeth Flood.

But, I don’t think a writer needs to necessarily jump into the big 5 to be part of the bridge. There are plenty of small press happenings, perhaps more so there than anywhere else: John Langan’s The Fisherman evokes Melville, Hemingway, and the great American fishing narrative to explore grief and loss. And I am always amazed by Nick Mamatas, whom I have already mentioned. My favorite work of his right now is The Last Weekend. It’s a poignant künstlerroman of a writer stuck in the middle of the post-apocalypse. But it’s also really just a mid-life existential crisis. He tries to rebuild his narrative that is constantly crumbling around him, in-between jacking up zombies, of course. I hate zombie books, so the fact that Nick was able to make me reevaluate the trope is saying something. To me, Nick is a “writer’s writer” but he’s so damn good you don’t realize that what’s happening. And really, I think that’s the rub, right — it’s about the writing. No matter which side of publishing you are on, it’s the writing that is going to transcend the bullshit.

Van Young: Last, not least, what’s with the title? Is it supposed to evoke some double-meaning?

Chambers: Yup! Calls for Submission refers to the two overarching elements of this book. First, there’s the career track…how these stories came to be. Almost all of them were written for anthologies or magazine themes. The only exception are the oldest stories, “The United States of Kubla Khan,” and “Of Parallel and Parcel.” Everything else was written in response to some form of a submissions call.

The second meaning refers to the collection’s overarching theme. I am fascinated by quieter forms of revolt, and each character in this story has some battle to subvert. Each story looks at how the character reacts when called to submit to something more powerful than them, be it government, illness, secrets, or worst of all, themselves.