writing life

Things We Don’t Write: K. Anis Ahmed On The Murdered Writers Of Bangladesh

We’ve asked some of our favorite international authors to write about literary communities and cultures around the globe. We’re bringing you their essays in a new ten-part series: The Writing Life Around the World. The fourth installment is by Bangladeshi author K. Anis Ahmed.

Dhaka, Bangladesh

Things we don’t write about: The Prophet. The Quran. The mosque. The hijab. Indeed, anything to do with Islam that might offend anyone willing to kill. The problem is that we can never be certain what will offend them. The killing types are no longer visible, wizened old men who regularly announce where the red line lays. The mantle has passed onto teenagers wielding machetes, belonging to secret cliques, guided by international ideologies with vicious local consequences.

Four bloggers have been hacked to death since the beginning of this year…

In a bewildering new trend, it is young rationalist bloggers in Bangladesh who have emerged as the primary target of Islamic extremists. How peculiar indeed, that killers espousing a retrograde vision of the world should be so obsessed with the most twenty-first century of media: the blog. Four bloggers have been hacked to death since the beginning of this year, and dozens more live in fear of becoming the next victim.

There is a specific history at play here. The secular bloggers of Bangladesh led a mass secular movement in 2013 demanding the death penalty for war crimes committed during Bangladesh’s 1971 war of independence. What’s unfolding now is in great part payback for the “insolence” of those seeking belated justice for a long-ignored genocide.

The first blogger was killed in 2013, at the height of the movement. Spring 2014 and Spring 2015 both saw an upsurge in political violence that targeted general civilians. At the same time, there was a renewal of blogger killings with the hacking of Avijit Roy just outside the Ekushey Book Fair. The Fair commemorates the 1952 Language Movement, which triggered Bangladesh’s eventual bid for full independence, and remains one of the most cherished symbols of the country’s cultural identity. To kill a free-thinker at the site of that cherished event was a deliberate attack on not just the victim, but on all those who shared his vision of Bangladesh as a bastion of secular, progressive ideals.

* * *

What then does it mean to be a writer today in this, Bangladesh’s “new normal”? When I wrote my first complete story back on Thanksgiving Day in 1989, I did not imagine this future for my country. Like any young writer, I was consumed with putting the story together, making it cohere, making it interesting. Like others of my age, I also cultivated an appropriate amount of existential angst — having just recently discovered Camus, Sartre, Kafka and Kundera, that seemed like a prerequisite for becoming a writer of any worth.

But 1989 was a signal year in two opposed ways: it was the year that the Iranian regime passed its fatwa on Salman Rushdie for The Satanic Verses. It was also the year that Bangladesh’s nearly decade-long pro-democracy movement hurtled into a final phase, with an accompanying upswing in progressive cultural expressions.

…the theocrats had found a viciously efficient way to extend their grasp internationally.

The first of the two events, the Rushdie Affair, left an indelible mark on me as an apprentice writer. Even back then, a creeping realization came over me: the theocrats had found a viciously efficient way to extend their grasp internationally. I took the Rushdie affair as counsel to steer clear of the subject of religion. Apart from one early work, a novella (Forty Steps), I have rarely referred to any Islamic tenets in my fiction, and then too never in a critical manner. But to avoid the topic entirely is frankly impossible.

All writers are bound to mine the culture in which they were brought up, but in Muslim societies alone, there are classes of fanatics who have arrogated to themselves the power both to regularly denounce people for blasphemy, and to carry out their death sentences with horrific impunity. So while a high risk can attach to any author who dares speak of Islam, writers who count Muslim culture as a part of their personal heritage face the pain of having to treat the most natural of materials as one filled with toxic risk.

When Forty Steps was published in Bangla at the Ekushey Book Fair in 2006, a small troupe of self-styled Islamic guardians with their towering head-dress and long, flapping outfits marched over to the stall and demanded the book. It was an obscure literary work that used the popular lore of the angels Munkar and Nakir to frame the story. Hearing the incident, I was struck that even such an obscure, literary work should catch the attention of the self-appointed custodians of religious rectitude. In that instance, thankfully, the vigilantes left satisfied: stall, book, and my safety intact.

Even after that incident, though, some of my stories have turned to Islamic literary tradition as an integral part of the context of the narrative or a character. After all, no writer should have to shy away from material that is genuinely compulsive and important. But because there is no guarantee that the pathologically intolerant will agree, Muslim writers — and also others who find Islam or Muslim cultures to be a compelling topic — are thus finding themselves forced to contend with a heightened pressure of self-censorship, and mortal risk.

The condition for anyone wishing to write about Islam is thus comparable to dissidents of another era who lived under dictatorial regimes. In a twisted irony of globalization though, the risk is no longer confined by territory; it is outsourced to lethal effect. There was a time when political dissidents could escape their own country, mainly to the First World, and find a safe haven. For anyone tangling with Islam, however, there is no refuge on earth.

* * *

Life in Dhaka felt abuzz with creativity and defiance.

While the Rushdie Affair inaugurated a new era of Islamic intolerance, and even as it made a strong impression on me as an aspiring writer, I was however not worried about the atmosphere of my country at the time. As the pro-democracy movement came forward and eventually ousted the dictator Ershad, a spate of feisty new weeklies — Jai Jai Din, Bichinta and Khoborer Kagoj — became vocal against not only the military regime but also social orthodoxies. Life in Dhaka felt abuzz with creativity and defiance.

Khoborer Kagoj was owned by my family. Leading poets like Shamsur Rahman and Syed Shamsul Huq wrote weekly columns there. Authors like Rafiqul Islam, M. R. Akhter Mukul and Bhasha Matin provided witness to the country’s history of progressive struggles from the Language Movement of 1952 to the Liberation War of 1971. Self-proclaimed atheists such as Ahmed Sharif and Humayun Azad commented freely against dogma. One of the most sadly famous of Bangladeshi authors today, Taslima Nasreen, made her debut as a columnist.

It was hard to imagine in those heady and hopeful days that the roster of Kagoj columnists would come to comprise a wretched honor roll of victims, as anti-liberation forces gained power by attaching themselves to a mainstream party: Nasreen was hounded into exile in the early 90s. A decade later, Rahman, by then an aged laureate, suffered knife wounds from an attack by fanatics in his own home. In 2004, Azad, an outspoken critic of Islamism in politics, was struck outside the Ekushey Book Fair — like the blogger Avijit Roy this year — and died later that year in Germany.

There is of course a deeper history here. Bangladeshi authors have faced Islamist reprisals long before the era of petro-dollar-fueled Islamism. Like the poet Daud Haider who was imprisoned “for his own protection” in 1973 after coming under attack by Islamic clerics of entirely indigenous make. He later escaped into exile and to this day lives in Germany.

Much closer to home, quite literally, my grandfather was also taken into “protective custody” a year after Haider’s troubles, for similar offenses. An eccentric autodidact, he had penned a book about language and literacy, but clerics took an exception to a particular chapter in the book that touched on religion. Thanks to the ill-fated intellectual adventure of my grandfather, my earliest memories include the warden’s room in Dhaka Central Jail: high ceilings, a large black desk and glass-cabinets full of moldy files.

Given that I was initiated into the dangers presented by the most narrow-minded custodians of Islam at an early age, I should not be entirely surprised at the vicious new bloom of bigotry. But at the same time, the spirited free-thinking days of the early ’90s is also an equally authentic part of our heritage and who we are. Our war of independence was in fact fought over these divergent ideas of who we wanted to be: a country that believed in freedom and dignity, or one that prized prejudice and proscriptions.

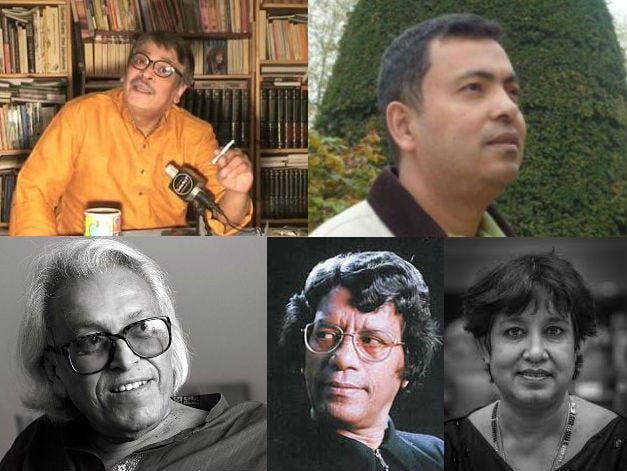

clockwise from top left, Daud Haider, Avijit Roy, Taslima Nasreen

Humayun Azad, Shamsur Rahman

* * *

The Blogger Killings mark the most brutal new assault by the forces of prejudice. Indeed, not since the Liberation War of 1971 have we seen such concerted violence against free thought and free speech. At the peak of the Shahbagh Movement, a section of Islamic clerics presented the government with a list of 84 bloggers they accused of blasphemy. All the bloggers killed this year are names that had appeared on that list. A few, like the latest victim Niladri Niloy, could not save himself even after he changed his job and his residence. Everyone on that list thus remains utterly vulnerable to an attack at any moment.

It would be comforting to frame this Islamism only as an outside influence, but that would be a sad self-deception in a culture where a majority of the people, according to some recent polls, now believes that blasphemers should be hanged. Bangladesh’s Blogger Killings are thus not caused by sudden upsurge of Islamism, but related to a long-running political contest between two visions of the country: secular and progressive versus Islamist.

Two decades of economic progress has made us soft. We no longer have any appetite for political or idealistic fights. The good are lacking conviction, even clarity, while the worst are bristling with passionate intensity.

Now they say, if only bloggers would simply show some restraint, then there would not be so much commotion. But recent history has taught us, feeding the tiger only gives it greater appetite. Recently, new hit lists have been issued naming a much wider range of people — politicians, academics, activists. All the persons named so far are leading figures in their respective fields, with no record of criticism of Islam, but invariably with a progressive bent.

The space for freedom is rapidly reaching a level of constriction not seen since the days of the harshest military rule.

The net effect of issuing lists and the actual killings is a systematic silencing of progressive voices. What’s more, the state, too, has been passing laws that are inimical to free speech. When young men and seasoned journalists get jailed for posting thoughts on Facebook, it is hardly a shining moment for freedom of speech. The space for freedom is rapidly reaching a level of constriction not seen since the days of the harshest military rule.

The deteriorating situation in Bangladesh increasingly presents me with an artistic dilemma too. A climate of interdictions, and worse, not only limits one’s ability to draw upon one’s natural cultural resources, but also it effectively calls on us to take up an oppositional role. I resent letting the forces of evil set the agenda of my writing. At the same time, not to respond to changes in my environment would also be forced and unnatural.

Oh what a long way we have come from the courageous and conscientious standards of men and women who went to war for our independence! What a long and tawdry length we have fallen indeed even from the spirited days of our pro-democracy movement.

Do I wish I lived in a place where I would be free, in my fictional works, to roam territories that the most violent claimants of the earth know nothing about? Perhaps that question is self-indulgent. From Ovid’s Baltic exile to Nasreen’s homelessness today, from the execution of countless heretics and dissidents across cultures and centuries, to the young bloggers hacked to death in Dhaka today, to be under serious threat has been the more common condition for writers.

we are reminded that freedom is not something we inherit.

I don’t believe that one can say vital truths only by courting the worst of known dangers. That is not the role I aspired to as a writer. That is still not the kind of role I invite with any eagerness. Yet, as the bodies pile up, and society reacts with a distinct lack of sympathy, we are reminded that freedom is not something we inherit. It is something for which we may have to fight, again and again.

About the Author

K. Anis Ahmed is the author of several works of fiction: Good Night, Mr. Kissinger, The World in My Hands and Forty Steps. He is also the publisher of the Dhaka Tribune, a national daily, and Bengal Lights, a literary journal. He lives in Dhaka, and is currently at work on a new novel, about the misadventures of extreme foodies in New York.

You can find all the essays from The Writing Life Around the World at Electric Literature.

The Writing Life Around the World is supported by a grant from the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses and the New York State Council on the Arts.