Books & Culture

Tim Gunn Is My Writing Teacher

The “Project Runway” mentor is leaving the show, but not before getting me through my dissertation

Tim Gunn is leaving Project Runway, and I don’t know how to imagine the workroom without him. I mean the workroom on the show, but also my own office — because in the course of watching Runway obsessively while writing my dissertation, Gunn has become my de facto writing coach.

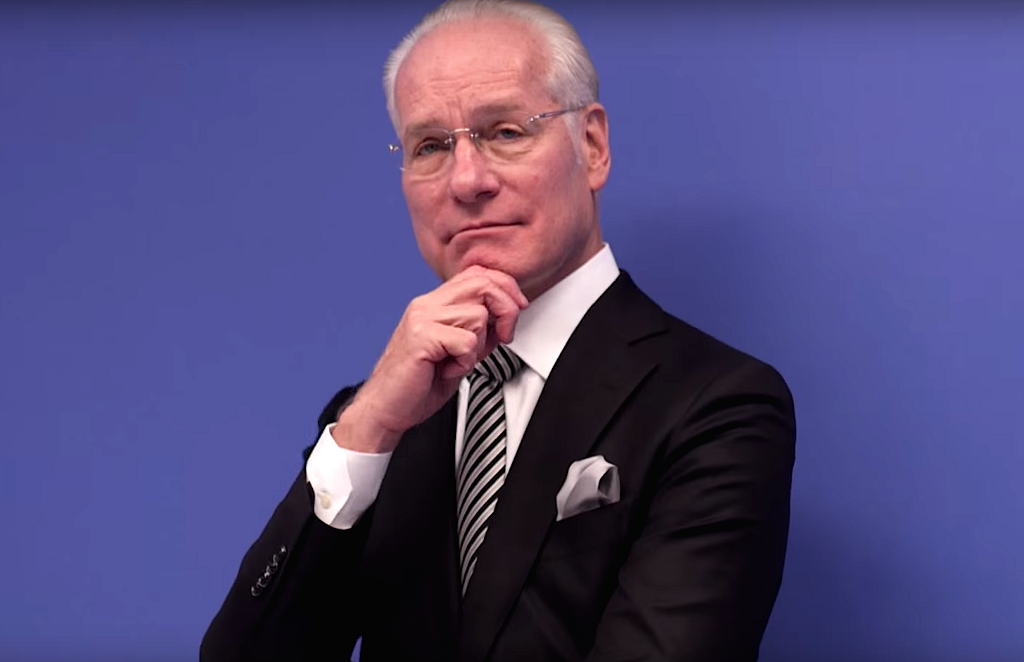

If you’re not familiar with Tim Gunn, picture a dapper white man who looks like he could be a friend to Princess Diana or Beyoncé: suited up, quietly smiling, respectfully standing next to the diva to give her a little gravitas. He’s impeccably dressed and unflappable, always, but when the chips are down, or when he’s worried about you, he will let his brow furrow in sympathy. Gunn is a vision of a certain kind of class personified; in his role as mentor to Project Runway contestants, he is never seen outside of a suit or without a pocket square. (He’s also one of the few white people besides Helen Mirren who never seems to age.) But more than looking nice, Gunn seems by all accounts to be genuinely nice and encouraging. His cheerleading has kept the designers on the show going for the decade and a half of its run, despite their high-pressure competitive environment. And as someone who tends to be hard on myself and my own creative and academic output, I’ve discovered that it keeps me going, too.

As someone who tends to be hard on myself and my own creative and academic output, I’ve discovered that Tim Gunn’s cheerleading keeps me going.

I started binge-watching Project Runway during spring break a couple of years ago while I was buckling down to do some work on my dissertation. Some people need complete silence in order to write; I need something ranging from white noise to actual noise. Silence gets me stuck in my head; other sounds keep me grounded and focused. I was struggling through taking some inchoate dissertation notes, before I knew what my argument was, when I thought to throw on Runway as a pleasant distraction. It backfired, somewhat, as I found myself getting more and more invested in the show. It wasn’t just the clothes, though that was part of it — the good ones and the bad ones. It wasn’t just the tantrums or the triumphs of the designers, most ill-equipped to function well in such a pressure cooker. It was the calming presence of that white man in a grey suit. He wasn’t just telling them they could do it; he was telling me.

Part of Gunn’s motivational appeal is structural. The judges who appear most often on the show’s run — former Marie Claire creative director Nina Garcia, fashion designer Michael Kors, and supermodel Heidi Klum — are often very direct to the point of harshness. They moved into that mode early, as in the critique in Season 5 that had Kors spitting, “It looks like toilet paper caught in a windstorm.” Kors’s commentary that season inspired Entertainment Weekly to knit together a poem of his most memorable critiques. Garcia is less lyrical, but no gentler, more likely to drop a devastating “I have no comment.” Klum is the judge who seems to take the most care with contestants’ feelings, partly because she often frames her critique as opinion, liberally using the phrase “to me” (though that care is a lot less evident when, as happens frequently, the contestants are actually designing something for her). Gunn falls somewhere in the middle of their approaches: when he has a harsh thought, he eases you into it, often asking, “May I be frank?”

Everything I Know About Writing a Novel I Learned from Watching British People Bake

His job is markedly different than the judges’ job: he sees in-progress garments in inchoate stages, sometimes when they’re nearly done, but more often when they are just piles of fabric or an idea (as with Season 8 and Project Runway All Stars wunderkind Mondo Guerra, who never drew sketches). Gunn accesses part of the imagined reality of the clothing when what the judges see, for better or for worse, is the final product. Despite the cameras and the other designers in the workroom, he somehow manages to carve out private moments with each contestant when he’s making his pre-runway rounds, offering advice, pointing out inconsistencies, and, usually, finding a moment to (genuinely, it seems) let loose his mellifluous laugh. (Go listen to it. It’s just lovely. It must calm some of the designers the hell down in an instant.)

As I got deeper into dissertation writing, I realized that, though I have an uncommonly wonderful, sharp-eyed, and supportive dissertation director, Tim Gunn is a great pinch-hitter when she’s not around. Writing a dissertation is a confusing and sometimes futile-seeming process. It’s like a really messy book. And it’s a really messy book that you get a lot of feedback from one person on (your chair), combined with possibly conflicting feedback from two to four more people on (the rest of your committee), as well as thoughts from anyone else who respects or loves you enough to wade through early drafts. As I get closer to finishing, it strikes me that the weirdest part about the whole thing, though, is that once you write one, you never write another one. It’s not entirely unlike designing a dress on the show: the situation is pressured, the stakes sometimes seem insurmountable, you may feel like you have no idea how to do it, there’s a likelihood that you’ll cry in public, and the finish line is you staring down a small group of people who are invested in your work but tend to tell you what they really think.

Writing a dissertation is like designing a dress on the show: the situation is pressured, the stakes sometimes seem insurmountable, there’s a likelihood that you’ll cry in public.

To work on a longform writing project is to launch yourself into a morass of feelings and ego in which you bumble around trying to make sense of still-forming ideas, and it’s in the deepest muck of this that Gunn’s motivational sayings are most helpful. “Make it work” is his famous, Yoda-like catchphrase that contestants sometimes mutter to themselves in the heat of a challenge. Its vagueness is the root of its helpfulness for a frustrated dissertation writer: when he says it, I hear the implied “you will.” You will make it work, Gunn is advising. He’s less lecturing than buoying up. You’ll find a way. This pile of fabric (or pile of expletive-punctuated draft pages) will become something real, and you just have to figure out how. It’s not his job to tell you exactly what steps to take, but he knows you can get there. Gunn’s description of how to be a good mentor, as he told the New York Times in 2013, is just like how to be a good writing teacher or dissertation advisor: “I’m here to guide, I’m here to support, I’m here to be the cheerleader, but you’re doing the heavy lifting.” (His own books include Gunn’s Golden Rules: Life’s Little Lessons for Making It Work and Tim Gunn: The Natty Professor: A Master Class on Mentoring, Motivating, and Making It Work!)

The least cynical understanding of a dissertation is that it is the culmination of an intense and long several year-period of study; the most optimistic (and most useful) understanding is that it’s the first draft of what will become your first academic book. The cynical answer is that it’s a hoop to jump through to get your degree. All seem true to me, and the interplay of feelings extends to other kinds of writing. Writers of all sorts and in all genres, I think, have to be simultaneously cynical and optimistic. We are constantly mucking around in the mess and magic of our own brains. We’re constantly getting excited and pitching and waiting and getting rejected and pitching again. Anyone writing anything longform, in particular, is likely to be wallowing in confusion at least part of the time, but the optimism is what keeps them coming back to their pages. Perhaps equally because I’m an optimist and a masochist, I do both academic writing and freelance writing, which means I’m usually moving back and forth between inspiration and exhaustion on any given project I’m working on. Not unlike Project Runway designers, writers have to repeat a lot of the same moves over and over again with fresh energy and in a bog of feelings that, even with the show’s cagey editing, clearly sucks them under and spits them out, too.

Not unlike Project Runway designers, writers have to repeat a lot of the same moves over and over again with fresh energy and in a bog of feelings.

Tim Gunn genuinely wants every contestant to succeed, and I believe that’s true of good dissertation advisors and editors as well; it’s definitely true of mine. They’re not just there to offer really cogent comments about how garments (or writing projects) in progress are going. They’re also there to hold the contestants up through a really pressured time. They help you figure out how to structure or edit this Behemoth Thing the likes of which you haven’t attempted before, and within that, they also do some cheerleading. (A notable difference is that sometimes Gunn is able to bring back a kicked off designer with his Tim Gunn Save; grad students struggling amid corporate university austerity aren’t as easily rescued.) My advisor wrote me a note I will never forget in November 2016, reminding me that when the world is burning down, writing is in some ways even more important. So, as Gunn has advised for 16 years, I’m making it work.