Books & Culture

To Set Something on Fire: War of the Foxes by Richard Siken

War of the Foxes, Richard Siken’s second collection of poems, begins where his debut collection Crush left off — the body. In “The Way the Light Reflects,” Siken writes, “I have my body and you have yours. / Believe it if you can. Negative space is silly.” Navigation of that space, both emotionally and physically, dominated the obsessive and hungry poems of Crush, which won the Yale Younger Poets competition in 2004. One of the recurring images in Crush was that of the poet’s empty hands, hands rendered vestigial by all they were not allowed to touch. In War of the Foxes, Siken puts those frustrated appendages to use by picking up a paintbrush. Gone is the savage sexuality of Crush, and in its place we find a painter alone in his studio; in fact, the few references to lovers in this collection describe them asleep in the next room, as if these poems were written in the quiet hours after Crush. And while the poems in War of the Foxes do sometimes read like entries from a painter’s notebook, they do, like the poems in Crush, refute the illusion of space, in this case the space between our bodies and the outside world. As Siken writes in the poem “Landscape with Fruit Rot and Millipede,” “The mind fights / the body and the body fights the land.”

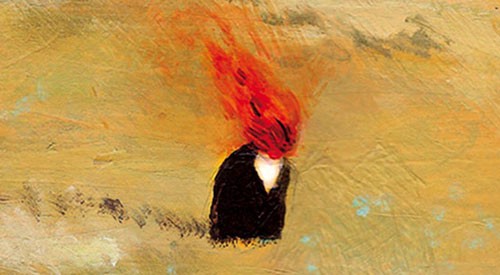

If the poems in Crush were engaged in the metaphysics of alienation, the poems in War of the Foxes are engaged in the metaphysics of creation, an aesthetic theory in which the boundaries of the human mind has drastic consequences for the natural world. In this way, the relationship between a painter and a landscape is similar to the relationship between men and nature: as soon as we see it, we can’t help but change it, alter it, dominate it. In the poem “Landscape with a Blur of Conquerors,” Siken describes the process of painting a field, a field “empty, sloshed with gold, a hayfield thick / with sunshine.” This image, infused with all the beauty and innocence of the garden before the fall, appears again and again throughout the collection. But simply painting landscapes is not enough for Siken — he must introduce a figure, a man. And what happens when you place a man in an untouched field? We all know the answer to that: “Land a man in a / landscape and he’ll try to conquer it.” Siken doesn’t shirk responsibility for this state of affairs, and instead further implicates himself by painting more and more men until “they swarm the field and their painted flags unfurl.” The message is clear and it’s political: these men “those people,” aren’t “the enemy;” aren’t “Republicans;” rather, as Siken writes, “They look like me. I move them / around. I prefer to blame others, it’s easier.”

Siken continues this inquisition in the title poem “War of the Foxes.” Here, Siken moves away from the metaphorical into the allegorical, searching for the roots of war through a series of elliptical stories. In one story, two rabbits named Pip and Flip are chased by a fox into their warren, where, huddled together, Flip tells Pip to hide inside of him. In another story, a boy faces the wrath of an abusive father after he spills a glass of milk. In the final story, a fisherman’s son becomes a spy, and part of being a spy is waiting at a chain-link fence to share secrets with other spies. Siken writes, “It’s a blessing: every day someone shows up at the fence. / And when no one shows up, a different kind of bless- / ing. In the wrong light anyone can look like darkness.” This is another example of Siken implicating himself, and the reader, by showing us that we are responsible for creating the illusion of separation between “us” and “them,” and that this illusion has dire consequences. As Siken writes in the poem “Portrait of Fryderyk in Shifting Light,” “Everyone secretly wants / to collaborate with the enemy, to construct a truer / version of the self.”

If this all sounds very abstract, that’s because War of the Foxes is abstract. It’s challenging in a way that Crush was not; you read and re-read the poems in Crush just to savor the language, the images, but with War of the Foxes, you read and re-read the poems in an attempt to divine meaning. If Crush resembled the manic poems of Sylvia Plath, War of the Foxes resembles the cerebral mediations of Mary Ruefle. And like Crush, War of the Foxes is obsessive, relentless, but when the obsession was rough sex in motel rooms and cars speeding away into the night, the obsession felt like passion. In War of the Foxes, the obsession with painting, with representation, mimesis, and even mathematics and logic, makes the collection feel like a lecture. In one poem, Siken writes, “When you have nothing to say, / set something on fire. A blurry landscape is useless.” The reader can’t help but agree. We wanted to see the fire.

by Richard Siken