Interviews

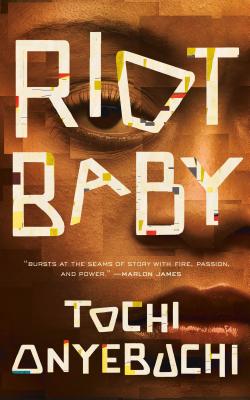

A Superhero Fueled by Righteous Anger

In Tochi Onyebuchi's "Riot Baby," Ella's psychic gifts carry all the energy of a political protest

If you pick up a Tochi Onyebuchi book you can always expect something hard-hitting, fantastical, and continually relevant, no matter where you’re from.

Onyebuchi’s novella Riot Baby spans time, place, and reality, following siblings Ella and Kevin (Kev) through pain they witness and experience personally. The book begins on the day of the 1992 L.A. riots—after the acquittal of the cops who attacked Rodney King. On this day of upheaval and duress for Black communities, the effects of which sadly reverberate to this day, “riot baby” Kev is born. Ella has a front-row view of not only the fires flaring around her, but of those that have burned through generations of oppression: a “gift” that feels like a curse, a Thing inside her. Ella’s twin traumas of violence and her “gift” carry through to the present day, as she’s burdened with knowledge, emotions, and powers she’s not immediately able to control. When her brother is assaulted by police and arrested, Ella must try to find a way to utilize this Thing for actual change in the larger world and within her family, starting with Kev.

This is Onyebuchi’s fourth book, so it’s not his first time exploring the dynamics of race, our pasts and futures, and how power structures aim to inhibit rebellion. It was a pleasure to talk with him about those themes, what makes a “villain,” and how social media and more awareness of the wrongs in the world can be a burden carried both by his characters and by us in our day-to-day lives.

Jennifer Baker: I wanted to start with the superhero mythos and the differences in building a stronger narrative. In Riot Baby we’re really looking at character building. This isn’t an origin story. You’re depicting how a person deals with differences within the society that made them and how society further makes them when they have this attribute (Ella’s “Thing”) that can be incredibly volatile.

Tochi Onyebuchi: I love how power can congregate characters. So you have the hero, and it’s generally understood that as the hero unlocks more and more of their powers, it’s generally a power that comes from within them. It’s not necessarily a power that’s granted to them from an external source. There are all these instances of characters in tough situations unlocking something within them, or there will be a very emotionally tense situation in the midst of a battle, and they have that moment where they tap into something that ignites them, and allows them to save the day. So there’s that trope, but another one that fascinated me were those deal-with-the-devil mythos, where you have this quest, but you’re not powerful enough to fulfill it right now. But, you make a deal essentially with this external phantasm to grant you the power to fulfill that quest. But there’s a dark side. You don’t think you’re a villain because you’re going to, for instance, avenge your loved ones. You don’t think you’re a villain, but over the course of that you become a villain. The power you tap into goes feral. It allows you to lose the essence of what it’s like to be human. That was always something that really fascinated me, which was that you have your powers, but we’re always going to be human. We’re going into the future and we’re still going to have, at least in my imagination, racism, classism, misogyny, all of those things in space. It’s not like we’re going to leave the atmosphere and those things vanish or they get stuck in orbit and then once we transfer we’re free of those baser impulses.

JB: That perceived freedom isn’t an option, it seems, even for your characters Ella and Kev.

TO: Yes, exactly. When you have a character like Ella who, like a lot of Black kids in general growing up in the recent past and present of America, where there’s constant racial trauma that’s happening, and you grant them super powers, they’re going to be taking their trauma with them. It’s not as if the powers erase memories of families or siblings that are lost in a shooting. It’s not going to erase all those memories of microaggressions, like how they tried to get off an elevator and a white lady walked on before they had a chance to get off. That was definitely really important to bring to the character of Ella, and also to Kev. They have really interesting journeys with anger, like whether or not anger can be productive.

What would it look like to have a hero, or potentially an anti-hero, who has that anger, that drive that’s in a lot of protest movements?

I think with a lot of the protest movements that have been happening lately in the United States, one of the things that I’m constantly noticing is that the powers-that-be will try to quell that anger and try to police how protests happen. “Oh, you shouldn’t be blocking the freeways. Oh, you shouldn’t be making so much noise. There are better ways to protest.” In each instance, they’re trying to leach the protestors of their anger. I think in a lot of ways anger is the catalyzing ingredient. When you have a protest without anger you’re defanged. Anger is that engine that’s driving it. What would it look like to have a hero, or potentially an anti-hero, depending on how you look at Ella, who has that anger, that drive that’s in a lot of protest movements, and she has this power, right? And Ella has a very different journey with anger than Kev because Kev starts from a very strong personal angle. It’s very localized and very immediate, and basically all the things being lower class and Black in urban America, all the things that could trigger that anger. It takes him through incarceration, and one of the things that he learns, one of his transformations, is how to quell that anger because you see how it can become a destructive force in his life. That’s the lesson he’s sort of taken from it. “Okay, anger got me into a lot of these situations. Anger got me here. If I just play the game, I can make parole. I can live a peaceful life. I can be a free citizen again.” But Ella is like, “Look, all the things that made you angry are still there, and it’s not going to change if you’re not angry enough to change it.” For me it was very, very important to have anger be such a vital ingredient in their journey.

JB: When it comes from quelling the anger, “don’t be angry” or “I just don’t want you to be mad at me,” all these things that push against pain, because people just want us to all just get along. You kind of tap into that with the Rodney King introduction.

TO: That was one of the things that was going through my head as I was writing this. It’s funny because with that particular chapter, even though it’s the first chapter in the book, it was the last part that came to me. In a way, it was the thing that tied everything together. Because before, it wasn’t necessarily this disembodied journey that these two characters were going on, but it didn’t necessarily have the center that I wanted. That’s why working with [my editor] Ruoxi Chen was such a dream because she helped nudge me, she pushed me to look for it. I was like, “That’s it!” This is the thing that made them. This is the thing that they came out of. Once that happened, it all clicked, and when I was writing it, I was thinking of Rodney King and “why can’t we all just get along.” There were thoughts that kept coming up in my head saying, “because you won’t let us.” If it were up to us, maybe things would be different, but they won’t let us. That was a big thing for me. Looking at the current political situation, Black people, people of color, we’re all voting the way that we need to vote to change things, but it’s the rest of the world that’s messing that up, right? We didn’t get 45 elected. You all did.

JB: And that’s essentially the conversation that Ella is having with Kev.

We can’t just play the game. We have to break their shit.

TO: Exactly. There’s a very personal connection to it, where it’s like, “Okay, you just gotta survive this. Let me help you through this.” But there’s also the complication of, “Well, this is the situation. This is the dynamic. We can’t depend on them to change it.” The change we need to enact needs to be rapid, it needs to be all-encompassing. We can’t just play the game. We can’t just protest or make noise the way they want us to make noise. We have to break their shit.

JB: From the get go, Ella seems so in tune with her body, the world, everything. It feels like at no point is she allowed relief. And Riot Baby re-emphasizes what we just said: That knowledge is power, that ignorance is bliss, but knowledge is necessary, but you’re burdened with knowledge. You’re burdened with awareness. I don’t think it’s horrible to have, but I do feel like it’s a burden in the world that we live in today. It really feels like that symbolism is very, very key here.

TO: That’s definitely a dynamic that I wanted to replicate with this book. You don’t have to wait for the police to release the footage of the shooting. You will get the Facebook livestream. All of a sudden we’re all exposed to this vicarious trauma, that we might have been shielded from it in the past. I heard about Sean Bell and about Amadou Diallo, but I saw Philando Castile die. It’s the same event, but you witnessed that event. And that did something to me. That did a very very big thing to me, and that might not have happened if I hadn’t heard about it in the Chicago Tribune or the Chicago Reader or read about it in the Times or the Washington Post or something. I think it’s important to know these things, but it can be a burden. For black people, for people of color that are constantly dealing with this reality of living in an oppressive society, it’s that added burden of, “Oh, also this is happening.” Even though it’s not in a place where I live this is also happening. What I think it is for white people who don’t necessarily have to deal with an environment of constant microaggressions, constant questioning of their experiences, constant gaslighting with regard to experiences based on their race, they find out about this thing, and they’re like, “Oh, I didn’t know this was happening before. Now I know.” Or “I didn’t know this was happening before, but I need more evidence to believe.” They’re starting from a different place, and so it’s very interesting to see what is happening with the conversation with regards to the necessity of this kind of burden. For Riot Baby, a lot of it is based on people I know, people that I’ve met, the stories and the experiences that they’ve told me. These are all real stories. Those are all very, very real stories. But my impression, fair or unfair, is that a lot of the readership don’t really know about people like this. They don’t know people in Rikers. They don’t know what happens there. They know, maybe, academically that people are there, but they don’t know that they’re human beings that are having these experiences.

You don’t have to wait for the police to release the footage of the shooting. You will get the Facebook livestream. All of a sudden we’re all exposed to this vicarious trauma.

JB: To me there’s an elevation in conversation by utilizing the speculative perspective. This genre elevates the story in a way that, I think, forces us to look at things in an even more realistic way than if it was just a “straightforward” story. Do you feel similarly?

TO: Absolutely. I also have a personal investment because it’s what I grew up reading and writing. It will always be my first love. One of the things that speculative fiction does is it operates on two levels simultaneously. It has more than one reality. A very obvious example is the civil rights struggle. You can make all these parallels. You can also have all these quote-unquote stories, and you can have all these issues. I think in the past, the characterization would be that these issues would be leveled in, like “Oh, this would be a parable about gender roles.” You look at Parable of the Sower or The Handmaid’s Tale and see all the different messages with regards to gender dynamics and gender repression and, in at least in Parable of the Sower, racial oppression. There’s this plot that drives the story forward, and you can really extrapolate situations in a way that if you’re writing literary fiction that didn’t necessarily have even any fabulist elements to it, you might have to cover a longer period of time or you couldn’t venture into the future and speculate about what it would be like or how the continuing of certain socioeconomic trends would impact the public. And with speculative fiction, you have this freedom to do that, and what I think is fascinating is that you loop that back on a story that is grounded in this almost photo-realistic present. So that was something I wanted to do with Riot Baby, which was really drive messages home and not have to risk that what I was saying about race being buried underneath levels of allegory.