essays

Trauma, Storytelling, and Time Travel

A writer questions the reliability of witnessing her own experience and the faithfulness of narrative

“I live on West 76th Street, near Broadway,” said the mother on the playground, as we watched our girls romp on the jungle gym.

I hesitated. Then I replied that I had a friend who had jumped out a window on that block many years ago. “That man was a friend of yours?” she asked. I was taken aback; evidently the story had traveled the neighborhood and was a frequent anecdote. I thought of Mrs. Lovett in Sweeney Todd. “My, you do like a good story, dontcha?” she asks Sweeney suggestively.

Who doesn’t?

I have my three-year-old in the stroller a few days later; we are headed to another playground in Riverside Park, which is perched above the waters of the Hudson. The sun shines brightly but the wind is sharp.

We frequently walk up and down Broadway, my toddler and I. We arrive — it seems — quite suddenly at the corner of West 76th Street.

On most days, this is just another bustling corner of Manhattan. Today I decide it isn’t.

I pause — just for a moment, because my child is not the sort to appreciate a break in momentum. Then I turn onto 76th.

I used to live on this block. I used to live there with a man named Joe.

Eleven years ago, the doorman found Joe’s body below the window of the apartment we’d shared. The doorman had gone to sweep leaves from the previous night’s storm and there was Joe — rain soaked, crumpled — in the middle of the courtyard. He had jumped in the night.

Eleven years ago, the doorman found Joe’s body below the window of the apartment we’d shared.

Joe didn’t leave a note.

I point to the maroon awning.

“Mommy used to live there,” I tell my daughter. The man at the newsstand remembers me and waves when I pass, even now, a decade later. Joe used to buy me magazines and candy at this newsstand. He loved to bring provisions — to sneak luxuries into the tower, to comfort the prisoner. One day he found me watching Fatal Attraction on cable; he laughed raucously.

“Mommy used to live there,” I say again. “Let’s go inside.” I roll the stroller into the building.

I see the doorman who found Joe’s body; he’s on duty today. Jeanne smiles at me to demonstrate that he remembers me. He called the police a lot when we lived there — either to keep me safe or to appease neighbors annoyed by the noise.

“Is this your little girl?” Jeanne asks. She looks just like you!”

Is he wondering if I’ll bring it up?

“How old are you?” he asks my little girl, trying to win her with a smile.

When a man asks my daughter about herself, I don’t like it.

“She is three,” I tell him.

Joe had me followed by a private investigator. He put software on my keyboard so he could read everything I wrote and sent. He woke me to berate me — nothing could wait until morning. Once, after reading my diary, he tossed me like a rag doll onto the doorstep, in my nightgown; then he slammed and locked the door.

My daughter escapes her stroller and jumps up the steps leading to the elevator.

Do I only think I remember the red and gold pattern swirling on the carpet below me? I see myself walking across that carpet twelve years ago — the day I moved in. Joe had just given me a small diamond ring. He’d taken me to Fifth Avenue and I’d sleepwalked up the aisles of Tiffany with him, listening to him ask questions about cut and clarity. He gripped my hand.

Do I only think I remember the red and gold pattern swirling on the carpet below me?

I wanted to vanish and reappear inside my father’s dusty study in California, to be a child again, running my fingers along the edges of his books. Or, better yet, to hear my mother’s voice meting out advice — advice that I must have missed. Or did I? Did she advise me about these things? Or would she have been unable to imagine her daughter in this predicament?

I found the restroom — Tiffany has many floors and the elevator took a while so when I got there the impulse to vomit had passed. I sat on the plush couch in the ladies’ lounge room and waited for Joe to forget I was there. But he was just outside the door when I emerged; he was pacing, sweating. What, he asked, had taken so long? He took my hand again and returned me to the diamond counter. On the way, he shoved the small of my back and when I stumbled, he smiled and caught me just before I fell.

Joe was once profiled in GQ; he was not famous but he caught a photographer’s eye as he walked down the street one day. He used to say it was silly; he was not handsome; he was a PR executive, not a model. It’s true, he was not handsome. His bright blue eyes gleamed with feral rage, he twitched anxiously and smoked compulsively. He could not go long without a cigarette and the deep lines in his face revealed a body ill-cared for, shrouded in paranoia and agitated depression. The GQ spread was framed on his wall, which amused me considering how disdainful he claimed to be of the whole enterprise. How easily our hypocrisy shows! It might have been lovable or charming had he been a nice guy; everyone hides things and everyone displays other things that misrepresent. Everyone engages in faux modesty and subtle half-truths at times. Whether we are charmed or repelled by a person’s inconsistencies is merely a question of what it is that a person is hiding.

Sometimes I’m on a bus and I see Joe getting on at a later stop — I’m certain of it. I get off at the next stop and I don’t make eye contact. He is dead twelve years but sometimes he boards buses I’m riding.

Jeanne the doorman studies me. “I’m glad you are okay,” he says. That’s as much as we’ll talk about it. I’m certain Jeanne was thrilled to find Joe in the courtyard that rainy night. He hated Joe, but that’s not the reason he’d be pleased. It made for a great story. I know how Jeanne felt. I used to say: “I drove my boyfriend up the wall — and eventually out the window!” And people would laugh and then I would say, “No, really!”

Everyone engages in faux modesty and subtle half-truths at times. Whether we are charmed or repelled by a person’s inconsistencies is merely a question of what it is that a person is hiding.

Today, I’d wanted to show Jeanne my child. I’m a mother now. I am all the things I was before — an actress, a dancer, a person, but I stand up straight when I speak now. I’ve made sure Jeanne sees this so that I can leave our brief reunion triumphant.

The first time Jeanne called for the police, one of them said something about how common the whole scene was — a large apartment in a pretty neighborhood, and look what goes on behind closed doors. How ordinary, how routine we are, I thought. If anger and harsh words are common, I thought, if some degree of dysfunction is the norm, then happy couples must be fascinating.

Filling out paperwork for a restraining order is tedious. Taking photos at the precinct is a nightmare. I joked that fluorescent lighting is an actor’s kryptonite; it makes bruises darker, more purple, and it exaggerates swelling. “This isn’t a joke,” my mother scolded.

The last fight Joe and I had was over an actor who worked at the pottery shop at which I earned a meager wage. Joe thought I had seduced him. “When would I have done that?” I asked. I locked myself in the bathroom. I moved out two days later, packing a few things in secret, running toward the Broadway bus late at night. Perhaps I heard the clock ticking — counting the seconds before Joe detonated.

I went to free PTSD therapy after Joe jumped — Mount Sinai Hospital was doing a study. My counselor was pregnant. I filled out questionnaires but grew distracted by her belly. Surely I was not destined to have a husband or a pretty pregnant belly draped in a silk blouse.

We see this all the time, the policeman had said.

“No points for originality, then?” I had asked.

“This isn’t funny,” the cop said.

Not even morbidly so? I asked, but not out loud.

When I moved out, Joe came to my mother’s apartment, where I’d sought refuge, at two AM. My mother was out of town for the summer; I hung tough as he rang the bell and whispered at the lock. I sat frozen, wrapped in a quilt I’d won in a lottery at work. The quilt was exquisitely soft; its faded green flowers were meant to look vintage. It suggested a meadow, fresh air, homespun wisdom. It was my “new life” quilt. Someday it would be on a bed in a sunny room in a cozy apartment in some other Manhattan. I would find this other Manhattan — this is what I promised myself. I would make a new life. I didn’t answer the door. He rang the bell for over an hour, but I did not answer it. A few days later, he would plunge to his death — alone.

A police officer took me to dinner a few days after I’d moved out and before Joe jumped. He’d met me at the precinct, when I’d had the photos taken. He leaned in and advised me on how to tell if I was being followed. He’d done a sweep of the restaurant, he told me, before we sat down.

It was meant to turn me on. I asked him not to call me again — just because of timing, I told him. I didn’t want to hurt his feelings. He had a gun.

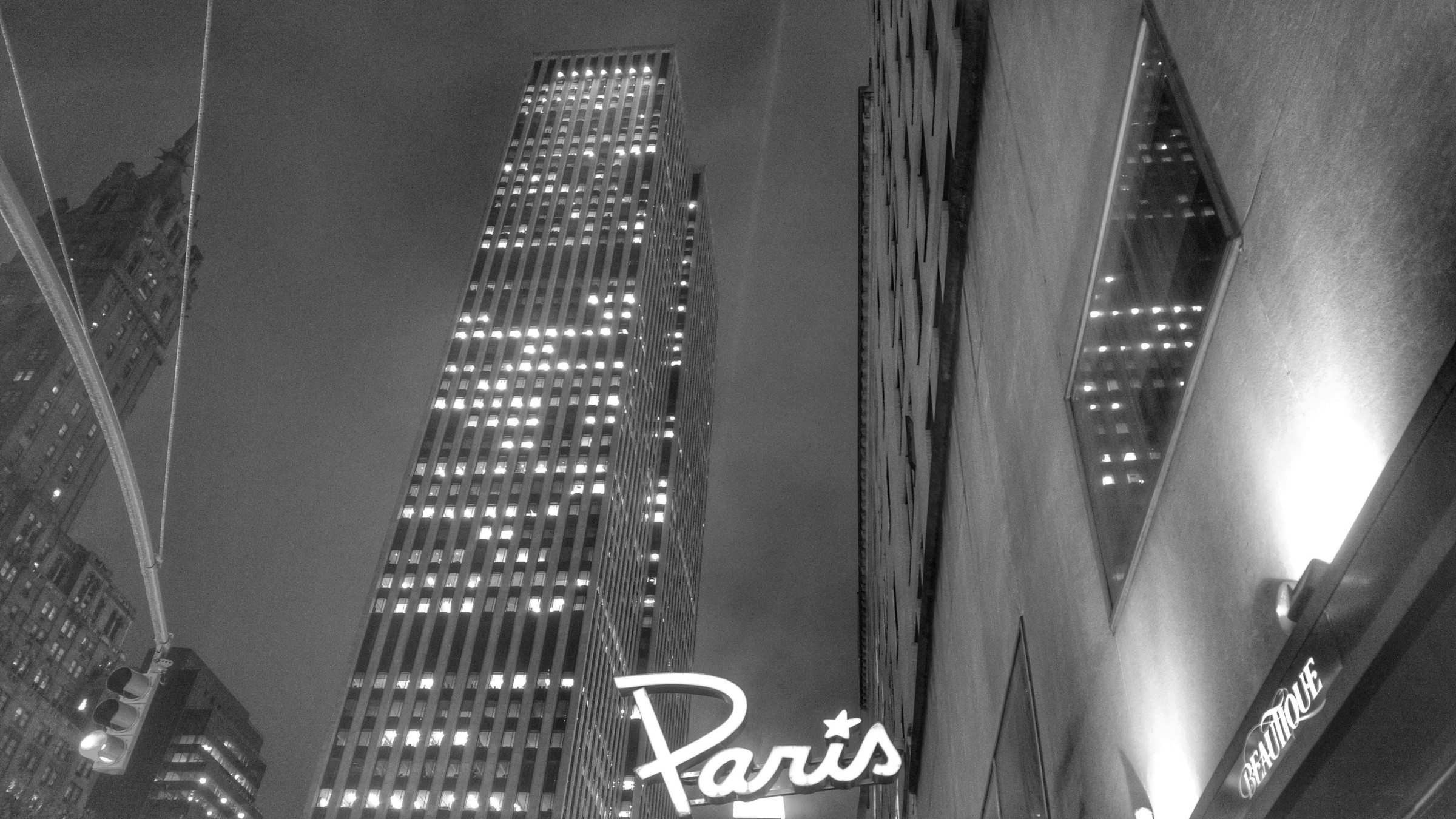

Three months after Joe died, I met my future husband. He asked me on a date and on the first night of December we saw a movie at The Paris Theatre.

Christmas lights flooded Fifth Avenue. Horses clopped by, leading carriages. If you squint on Fifth Avenue on a dark winter’s night, you can see top coats and bowler hats. You can see 19th Century passersby navigating a snowy thoroughfare. You can see Zelda Fitzgerald jumping in the Plaza Hotel’s fountain, or Eloise peeking from behind the curtains of the penthouse. You can see the other Manhattan of your dreams.

On our date, we didn’t pretend to be calm — we both felt nervous and shy. Still, I took off my shoes and crossed my legs when we’d settled into our seats in the theater’s lavish balcony. I trusted him.

On our date, we didn’t pretend to be calm — we both felt nervous and shy.

I had met Joe in an elevator. We’d only exchanged a few words before he reached over and pulled up my sweater, warning me that it was cut too low. He wanted to protect me, he said. I wore the same sweater to The Paris Theatre. My future husband didn’t touch my sweater; instead, he placed his hand just above mine, asking silently for my permission.I grazed my finger against his palm, giving him my answer.

Nothing Comes Back from the Dump

Our daughter looks like both of us. On this brisk spring day, we say “goodbye” to Jeanne and leave The Colorado. We buy a baguette at Maison Kayser — a French bakery on the corner of 76th that has replaced a previously bustling Greek restaurant called Nikko’s. There were rumors of money laundering at Nikko’s — something about how they moved on every few years to evade inquiry. No newspaper ever wrote up a story; it was merely whispers.

My daughter and I sit on a brownstone stoop and scoop out the baguette’s spongy interior. We watch New Yorkers departing their homes, checking cell phones, racing toward the subway.

Who wants to know a story like that about her mother? Not every “good” story should be told.

“Did you know Mommy used to live in that building?” I ask my toddler again. I don’t expect a response; the question is boring. Perhaps it will be a story for another day — a day many years in the future. Perhaps not. Who wants to know a story like that about her mother? Not every “good” story should be told. And is it a good story? In it, someone dies a lonely death. Still — in it, someone survives, escapes,and begins again. But who is to say if I’m telling the truth? More than a decade has passed and I can’t be sure I have everything right. No one can be sure she has everything right. And Joe isn’t here to defend himself. At least I haven’t used his real name.

My daughter and I stand up and stretch, and I gaze at the street I once lived on with a man I now call “Joe.” The Cerulean blue of the springtime sky electrifies 76th Street. I could stare at it all day.

“Mommy?”

“Mmm?”

“Can we please go to the playground now?”

A note from the author:

Two years ago, I found myself passing the same street nearly every day. I was always with my young child; she consumed my days, as toddlers do. As my daughter ran gleefully past this particular intersection, in a busy area of Manhattan’s Upper West Side, I was struck by the embodiment of my present day — my child — racing by a street that in my past had become endowed with darkness. For me it was not just an intersection in space, it was an intersection of two time periods. I used to live on that street, and a few things happened there, in a building just beyond the corner. Perhaps I had never sorted through those events properly, and as a result, I was compelled to revisit the street, not just in my mind, but on foot.

My child rooted me solidly in the present day, but if we strode up the street, could we slip through a portal to an earlier time?I thought a lot about the book Time and Again, by Jack Finney, as I began to write this story up. If we spend enough time in an old neighborhood or building, might we also travel in time? Might we sweep together the particles of the past and recreate the events that occurred there? Could we witness those events anew, could we see the old characters walking right by — so close you could hear them and smell them and touch them? It became an exercise in imaginative power — but was I summoning the past accurately or recreating it? And what, exactly, is the difference? The great acting teacher Uta Hagen said that we tell stories for reasons, we don’t simply re-live an experience for its own sake, and that when we re-tell a story, whatever compels us to do so shapes the way in which we tell it.

What, then, was my reason for telling this story?

My mother used to refer to a type of behavior she called “approach-avoidance.” The term perfectly describes my frame of mind when I wrote this. The subject matter disturbed me greatly but the exploration of a physical space that no longer held any danger fascinated me. I am a rational person, but I enjoy the idea of ghosts. Remnants of people and events remain in the machinery of the brain — they may fade but they never disappear altogether. If you seek out a ghost, if you name a fear, does it lose its power? I recently read that this is sometimes called The “Rumpelstiltskin effect.”

I approached a scary topic by circling the periphery, feeling around in the dark for sense memory rather than trying to face it head on. And so the essay came to be about things peripheral to the experience — it came to be about stories, and the game of telephone through which our stories pass on the streets of New York City, onto playgrounds, among strangers, and it also came to be about the side players in our stories — the witnesses — and the bits of wisdom they dole out, wanted or not.

Am I reliable?

Last night, I walked past the building again. I noticed that the lobby’s carpet is a dull beige — in my essay it is a swirling nightmare of red and gold. Did I remember wrong, conflating my anxiety at that time in my life with the color of the lobby’s rug? Maybe, maybe not. I visited the lobby with my toddler two years ago; maybe the rug has since been replaced.