interviews

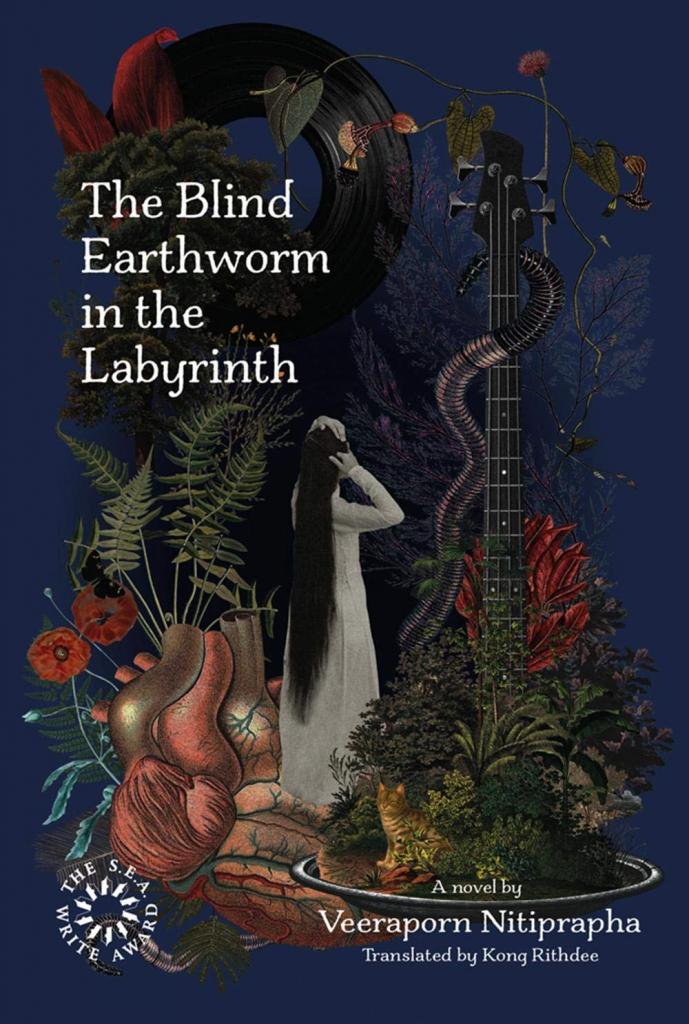

A Political Love Story Teeming with the Sewage of a Soap Opera

Veeraporn Nitiprapha tries to make sense of what's happening to Thailand in "The Blind Earthworm in the Labyrinth"

Veeraporn Nitiprapha’s debut novel, The Blind Earthworm in the Labyrinth, provides a haunting dissection of contemporary Thai life and its inescapable repetitions. Throughout the novel’s 27 vignettes, the characters—two doomed sisters, an orphan turned aspiring singer, a jilted mother gone mad from mistrust, a father dying of lovesickness, a Marxist boyfriend turned right-wing politician, and a navel-gazing wannabe war reporter—find themselves drifting through the dizzying paradoxes of modern-day Bangkok and its lush environs. As they search for love, glory, or anything that might rescue them from the fog of their respective despairs, Nitiprapha delivers a sweeping indictment of a society continually finding itself constrained by a derivative cycle of warped logic and fantastical dreams.

The Blind Earthworm in the Labyrinth won Southeast Asia’s most prominent literary award and became a domestic sensation in Thailand, due in part to its reverie-like vignettes designed to mimic the breeziness of Thai soap operas. Now, four years after the former jewelry designer and fashion-mag editor won her first of two S.E.A. Write Awards—making her the first woman to accomplish such a feat—Nitiprapha’s novel is available in English for the first time with a translation by the Bangkok Post’s film critic and lifestyle editor Kong Rithdee, who skillfully retains the poetics and absurdist nature of the original Thai edition.

Nitiprapha and I spoke about the “sewage-like” storylines of soap operas, how the toxicity of politics can make old friends vaporize, and how The Blind Earthworm became a laboratory for trying to make sense of the unsettling world around us.

Tillman Miller: The scope of The Blind Earthworm feels both intimate and epic, as if it’s one of the “Great Thai Novels” readers will continually revisit. How did the idea for the novel materialize?

Veeraporn Nitiprapha: Thailand has been going through significant political conflict since 2006, with street protests, rallies, and even domestic armed conflict, but it wasn’t until May 2010 that the right-wing government finally decided to crack down on a Red-Shirt rally in the middle of Bangkok, causing at least 2,000 injuries and 94 deaths, mostly at the hands of military snipers. These were unarmed people being killed by their own government, and frankly I was trying to cope with it. What bothered me deeply was how calm and even satisfied people were when supporters of opposing political parties were being killed.

During the seven-day crackdown in May, when the government declared a state of emergency, I met with this guy who I considered to be a moral and kind lifelong friend—a man who gave offerings to temples and donated to the poor, who adopted and fed stray dogs and cats—and I sort of unintentionally murmured to him, “They are killing people, bro,” and he replied, “It’s needed.”

The novel became a laboratory for making sense of the world, because it seemed as though everything had in some way stopped making sense.

I don’t know how to explain this, but right there in front of my eyes, this guy essentially vaporized into nothingness, vanished, became nonexistent. What had driven a good-hearted guy to become so heartless and cold-blooded? No one in this world should be killed for their beliefs—or their religion, their sexual preference, their taste in food or music, not to mention something as nonsensical as politics. So what was happening to us? What was happening to a country that I thought was so modest and nice and gentle-souled? I needed to understand this. I was 44 and already prior to the conflict I had an idea of writing a novel to impress my bookworm son—even if, ultimately, I didn’t write this book to impress anyone—I wrote it in order to survive mentally and to better understand the world around me. The novel became a laboratory for making sense of the world because it seemed as though every story I had ever known, and everything I had ever seen or heard had in some way stopped making sense. And so I felt forced to start writing this book.

TM: How can the larger themes—namely blindness to the truth and how people are trapped by personal beliefs from which they can never escape—say something about polarization in other parts of the world, including the United States?

VN: There is a blindness to one’s own self rather than a blindness to the truth. You never know which version of yourself is your true self, not to mention the truth of someone else. You can only know who you were before you become a nationalist, a martyr, an environmentalist, or a person protesting Tibetan massacres. You can only know who you were before you started wearing your pairs of designer shoes, before you got your degree from Yale and started driving a Porsche, before you bought a sleek condo and found the love of your life, before you started listening to Brahms and Beethoven or reading Kant and Marx or believing in gods.

What is so frightening isn’t that you can’t escape from the person you’ve become, but that most people don’t want to escape. Life—even after all the “greatest things in life” have been experienced—is meaningless and boring and unsophisticated. I guess this blindness happens everywhere in the world and it happens to the youth, to people in their middle ages, to the rich, and to the poor. There is a universal need for us to become someone we need not be.

TM: Your descriptions of Bangkok in the novel include: a “loud, mad city,” a “city of broken dreams,” “a city he had never loved,” and a city constantly finding “itself cloaked in an impenetrable haze that prevent[s] it from knowing the truth of what had actually happened.” How important was it to write about Bangkok as a complicated, alienating city, specifically in contradiction to the Westernized image of Bangkok as a city of liberation and hedonistic fantasy?

VN: Bangkok is one of the great places any writer would love to use as a background—every scene in the city has thousands of unspeakable implications, especially when considering things like myths and illusions. I was born and raised here, and I’ve stayed in Bangkok all my life, so I know the city well, but like all big cities in the world, behind the Bangkokian façade of vivid lights and expensive, beautiful, modern buildings is a city hiding its ugliness and disgraces: the over-killed garbage, the crimes, the prostitutes, the drugs, the poorest of the poor—all kinds of inequalities. You must also consider the official name of Bangkok, which is Krung Thep and means the “City of Angels” or something like heaven—a higher virtue, a divine inhabitant. Then consider how the political massacre of May 2010 happened right there in the heart of heaven, and yet all of the “angels” in the city were so calm, so relieved, even happy to see thousands of strangers being shot and killed. It made me bitter. I was overcome with a deep, painful bitterness seeing the fashionable, well-educated, well-paid people of the city feeling content about the injuries inflicted upon the poorer, less educated people who were mostly from the upcountry. And it was important to write about that bitterness.

TM: Many observers have compared this novel to Thai soap operas, in particular to the show Club Friday. Was it your intention for the vignettes to be “attuned to the rhythm” of these shows? And how is the storytelling structure of the novel similar to the structure of Thai soap operas?

I wrote this book as a love story teeming with the sewage of soap opera.

VN: In Thai we have a word for “sewage” (น้ำเน่า or nam-nao) —although “sewage” may not be the exact translation—it means something like “the water that’s blocked in certain spaces,” such as a pool or a drain, where no new water is able to come in and there is no way for the old water to go out. So the stagnant water becomes rotten, black, and smelly. And often we use this word to describe soap operas because they have the same old toxic storylines that keep repeating themselves, which is also very similar to how the general public keeps becoming involved with politics in the streets of Thailand. People get involved with political movements the same way they get involved with watching their favorite soap operas: they become full of emotions, myths, illusions, impossibilities, tears, and melodramas. In first-world countries, it seems as though people consider what they will gain from a political party and its policies before supporting a party. Over here, throughout the years, we just keep talking about good-guy politicians and villainous politicians as if we’re electing high priests into parliament. For most people it’s like watching television or a movie. People take the sides of the characters they like and then they feel compelled to follow those characters into the street. That’s why I wrote this book as a love story teeming with the sewage of soap opera—but it is a hypothesis only.

TM: Your description of the stagnant water reminds me of the way you described the once-pastoral canal in Bangkok where you grew up. How did that setting influence the settings in the novel?

VN: I was a happy kid growing up on the bank of that canal. It was close to school and located away from the busy main streets. There were few people in the area and even fewer cars and it was never hectic, so in a lot of ways it felt very rural and upcountry—both in the small-town way of life and in the natural landscape. In that way, I used the novel’s river setting to reflect the simple, pure, modest, and kind-hearted Thais before the most recent political conflict.

TM: I enjoyed how the myth-like stories in one vignette could seemingly reveal themselves to be actual stories involving two characters in a future vignette. Was this transference of myth to everyday life a way of showing how—in the words of the novel—we’re “a civilization reduced to legends”?

VN: Perhaps I did mean for the vignettes to demonstrate how things are reflecting each other though, such as the love story and the political conflicts, and the twin stars, Chareeya and Pran, the meeting and parting again and again, the repeating story of soap-opera plots in different settings and vignettes, and then the repeating of political conflicts in different vignettes. I think I was also trying to say that politics in general should not be as big of a deal as they are today. In an ideal world we shouldn’t have to fight over politics.

Still, I did write a lot about the aimlessness, emptiness, meaninglessness, and loneliness of society. I think getting involved in politics is also driven by this lonely, modern life in the city. It’s usually the middle class in the city—mostly Bangkokians—that start the nationalist demonstrations to overthrow the elected government and, in the end, they support the military coup. But what could drive people to the point of being angry modern-day nationalists 80 years after the start of WWII? Perhaps they see themselves as becoming some sort of heroes, but really their nationalist views are so meaningless and powerless and aimless. Sorry, I don’t know what has happened to my country. That’s why I keep writing, because I still don’t know the answers.

I don’t know what has happened to my country. That’s why I keep writing, because I still don’t know the answers.

TM: You mention the nationalists seeing themselves as heroes. This reminds me of the character Natee and how he performs in front of the mirror, seeing himself as a Hollywood hero. This leads him to pathologically lie about being a war correspondent to impress women. On some level, could Natee be seen as an archetype of the nationalistic mindset in Thailand?

VN: Well, on a lighter level, Natee could represent people who pay too much for name-brand products, people who try so hard to get into Ivy League universities, people who patiently cope with bad bosses and colleagues in order to stay in the most well-known firms and be seen as the “normal people” of the world. And yes, Natee could represent nationalists, too. There are people in my country who protest against the elected government and support the coups to overthrow it when they could simply just vote to make their voices heard. Maybe they daydream of becoming martyrs who save the country from a monster politician or a bad immoral devil. Maybe that’s why some people can feel relieved when a hundred people are shot dead and several thousand people are injured. I really don’t know. I wish I knew, but I don’t and all I can do is write to save myself from losing faith in humanity.